I wrote this post at about the same time Germany won the World Cup in Rio de Janeiro in 2014. There’s been a lot of moving and shaking in the world of exogenous ketones since then, not to mention soccer. Looking back on my post, I still consider it relevant in terms of what exogenous ketones possibly can (and cannot) do for performance. In this case, to see if exogenous ketone esters provide me a “boost” by allowing me to do the same amount of work while expending less energy (and work at a relatively lower VO2) compared to no supplementation.

I’m getting an increasing number of questions about exogenous ketones. Are they good? Do they work for performance? Is there a dose-response curve? If I’m fasting, can I consume them without “breaking” the fast? Am I in ketosis if my liver isn’t producing ketones, but my BOHB is 1.5 mmol/L after ingesting ketones? Can they “ramp-up” ketogenesis? Are they a “smart drug?” What happens if someone has high levels of both glucose and ketones? Are some products better than others? Salts vs esters? BHB vs AcAc? Can taking exogenous ketones reduce endogenous production on a ketogenic diet? What’s the difference between racemic mixtures, D-form, and L-form? What’s your experience with MCTs and C8?

Caveat emptor: the following post doesn’t come close to answering most of these questions. I only document my experience with BHB salts (and a non-commercial version at that), but say little to nothing about my experience with BHB esters or AcAc esters. But it will provide you will some context and understanding about what exogenous ketones are, and what they might do for athletic performance. We’ll likely podcast about the questions and topics above and cover other aspects of exogenous ketones in more detail.

—P.A., June 2018

§

Original publication date: August 14, 2014

Last year I wrote a couple of posts on the nuances and complexities of ketosis, with an emphasis on nutritional ketosis (but some discussion of other states of ketosis—starvation ketosis and diabetic ketoacidosis, or DKA). To understand this post, you’ll want to at least be familiar with the ideas in those posts, which can be found here and here.

In the second of these posts I discuss the Delta G implications of the body using ketones (specifically, beta-hydroxybutyrate, or BHB, and acetoacetate, or AcAc) for ATP generation, instead of glucose and free fatty acid (FFA). At the time I wrote that post I was particularly (read: personally) interested in the Delta G arbitrage. Stated simply, per unit of carbon, utilization of BHB offers more ATP for the same amount of oxygen consumption (as corollary, generation of the same amount of ATP requires less oxygen consumption, when compared to glucose or FFA).

I also concluded that post by discussing the possibility of testing this (theoretical) idea in a real person, with the help of exogenous (i.e., synthetic) ketones. I have seen this effect in (unpublished) data in world class athletes not on a ketogenic diet who have supplemented with exogenous ketones (more on that, below). Case after case showed a small, but significant increase in sub-threshold performance (as an example, efforts longer than about 4 minutes all-out).

So I decided to find out for myself if ketones could, indeed, offer up the same amount of usable energy with less oxygen consumption. Some housekeeping issues before getting into it.

- This is a self-experiment, not real “data”—“N of 1” stuff is suggestive, but it prevents the use of nifty little things likes error bars and p-values. Please don’t over interpret these results. My reason for sharing this is to spark a discussion and hope that a more systematic and rigorous approach can be undertaken.

- All of the data I’ll present below were from an experiment I did with the help of Dominic D’Agostino and Pat Jak (who did the indirect calorimetry) in the summer of 2013. (I wrote this up immediately, but I’ve only got around to blogging about it now.) Dom is, far and away, the most knowledgeable person on the topic of exogenous ketones. Others have been at it longer, but none have the vast experiences with all possible modalities (i.e., esters versus salts, BHB versus AcAc) and the concurrent understanding of how nutritional ketosis works. If people call me keto-man (some do, as silly as it sounds), they should call Dom keto-king.

- I have tried the following preparations of exogenous ketones: BHB monoester, AcAc di-ester, BHB mineral salt (BHB combined with Na+, K+, and Ca2+). I have consumed these at different concentrations and in combination with different mixing agents, including MCT oil, pure caprylic acid (C8), branch-chained amino acids, and lemon juice (to lower the pH). I won’t go into the details of each, though, for the sake of time.

- The ketone esters are, hands-down, the worst tasting compounds I have ever put in my body. The world’s worst scotch tastes like spring water compared to these things. The first time I tried 50 mL of BHB monoester, I failed to mix it with anything (Dom warned me, but I was too eager to try them to actually read his instructions). Strategic error. It tasted as I imagine jet fuel would taste. I thought I was going to go blind. I didn’t stop gagging for 10 minutes. (I did this before an early morning bike ride, and I was gagging so loudly in the kitchen that I woke up my wife, who was still sleeping in our bedroom.) The taste of the AcAc di-ester is at least masked by the fact that Dom was able to put it into capsules. But they are still categorically horrible. The salts are definitely better, but despite experimenting with them for months, I was unable to consistently ingest them without experiencing GI side-effects; often I was fine, but enough times I was not, which left me concluding that I still needed to work out the kinks. From my discussions with others using the BHB salts, it seems I have a particularly sensitive GI system.

The hypothesis we sought out to test

A keto-adapted subject (who may already benefit from some Delta G arbitrage) will, under fixed work load, require less oxygen when ingesting exogenous ketones than when not.

Posed as a question: At a given rate of mechanical work, would the addition of exogenous ketones reduce a subject’s oxygen consumption?

The “experiment”

- A keto-adapted subject (me) completed two 20-minute test rides at approximately 60% of VO2 max on a load generator (CompuTrainer); such a device allows one to “fix” the work requirement by fixing the power demand to pedal the bike

- This fixed load was chosen to be 180 watts which resulted in approximately 3 L/min of VO2—minute ventilation of oxygen (this was an aerobic effort at a power output of approximately 60% of functional threshold power, FTP, which also corresponded to a minute ventilation of approximately 60% of VO2 max)

- Test set #1—done under conditions of mild nutritional ketosis, while still fasted

- Test set #2—60 minutes following ingestion of 15.6 g BHB mineral salt to produce instant “artificial ketosis,” which took place immediately following Test set #1

- Measurements taken included whole blood glucose and BHB (every 5 minutes); VO2 and VCO2 (every 15 seconds); HR (continuous); RQ is calculated as the ratio of VO2 and VCO2. In the video of this post I explain what VO2, VCO2, and RQ tell us about energy expenditure and substrate use—very quickly, RQ typically varies between about 0.7 and 1.0—the closer RQ is to 0.7, the more fat is being oxidized; the reverse is true as RQ approaches 1.0

Results

Test set #1 (control—mild nutritional ketosis)

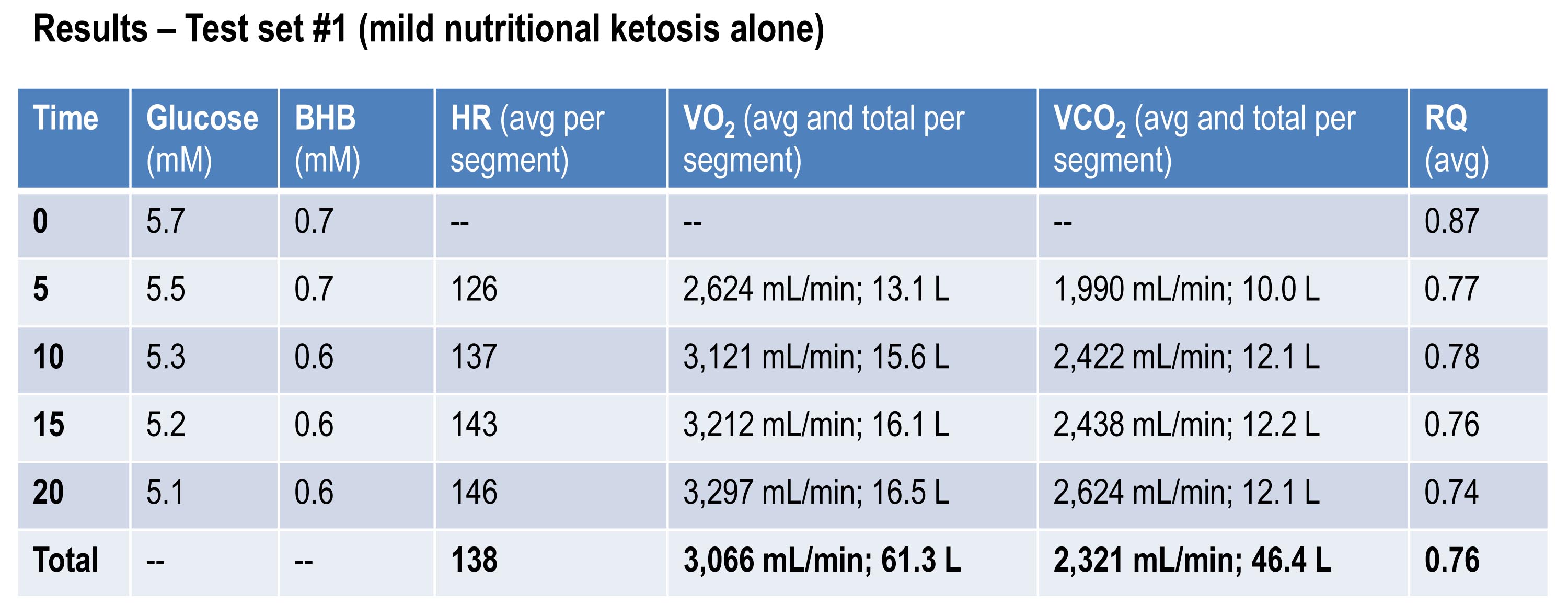

The table below shows the data collected over the first 20 minute effort. The 20 minute effort was continuous, but for the purpose of presenting the data, I’ve shown the segmental values—end of segment for glucose and BHB; segment average for HR, minute ventilation (in mL per min), and RQ; and segment total for minute ventilation (in liters).

Glucose and BHB went down slightly throughout the effort and RQ fell, implying a high rate of fat oxidation. We can calculate fat oxidation from these data. Energy expenditure (EE), in kcal/min, can be derived from the VO2 and VCO2 data and the Weir equation. For this effort, EE was 14.66 kcal/min; RQ gives us a good representation of how much of the energy used during the exercise bout was derived from FFA vs. glucose—in this case about 87% FFA and 13% glucose. So fat oxidation was approximately 12.7 kcal/min or 1.41 g/min. It’s worth pointing out that “traditional” sports physiology preaches that fat oxidation peaks in a well-trained athlete at about 1 g/min. Clearly this is context limited (i.e., only true, if true at all, in athletes on high carb diets with high RQ). I’ve done several tests on myself to see how high I could push fat oxidation rate. So far my max is about 1.6 g/min. This suggests to me that very elite athletes (which I am not) who are highly fat adapted could approach 2 g/min of fat oxidation. Jeff Volek has done testing on elites and by personal communication he has recorded levels at 1.81 g/min. A very close friend of mine is contemplating a run at the 24 hour world record (cycling). I think it’s likely we’ll be able to get him to 2 g/min of fat oxidation on the correct diet.

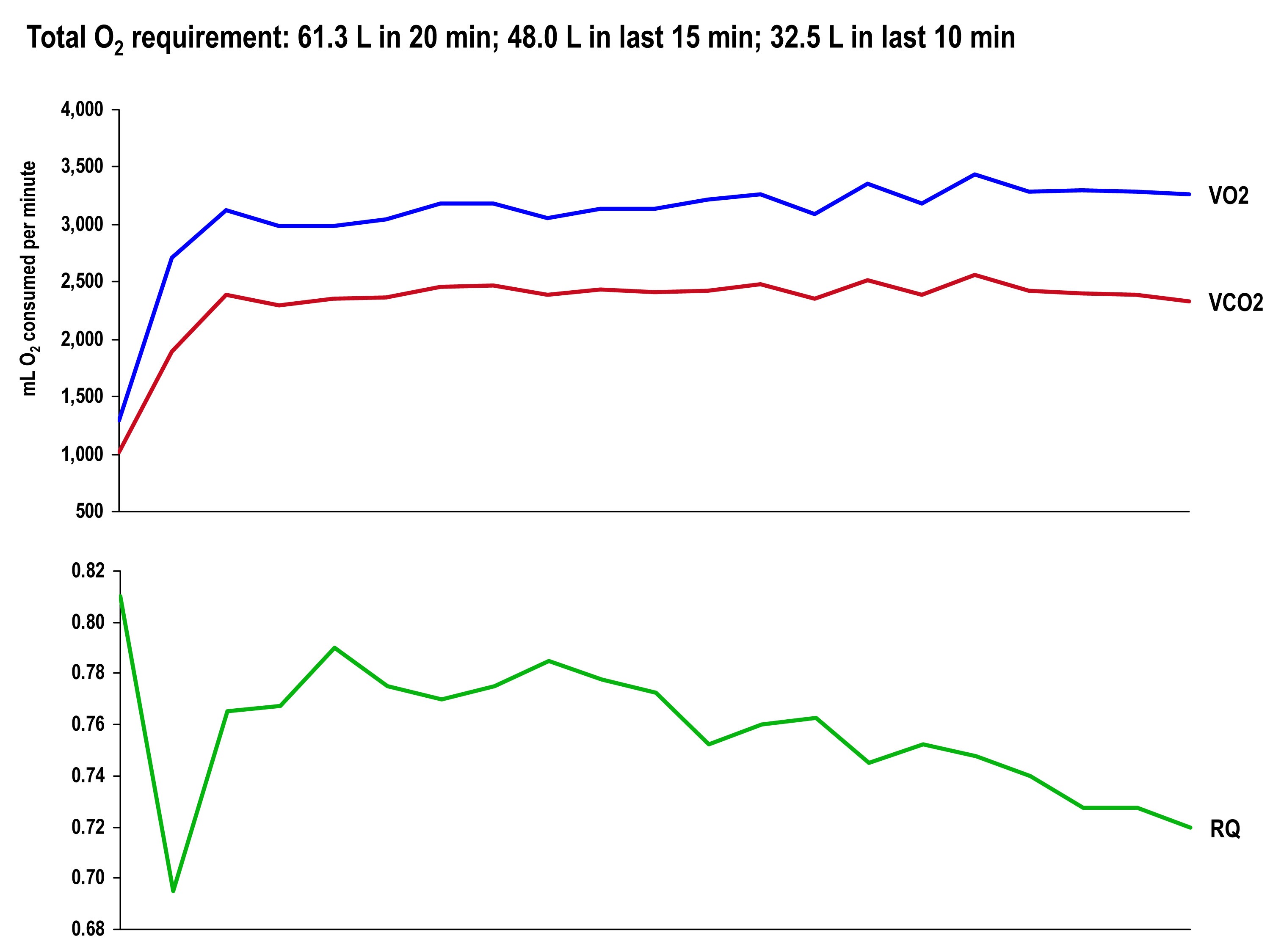

The graph, below, shows the continuous data for VO2, VCO2 (measured), and RQ (calculated).

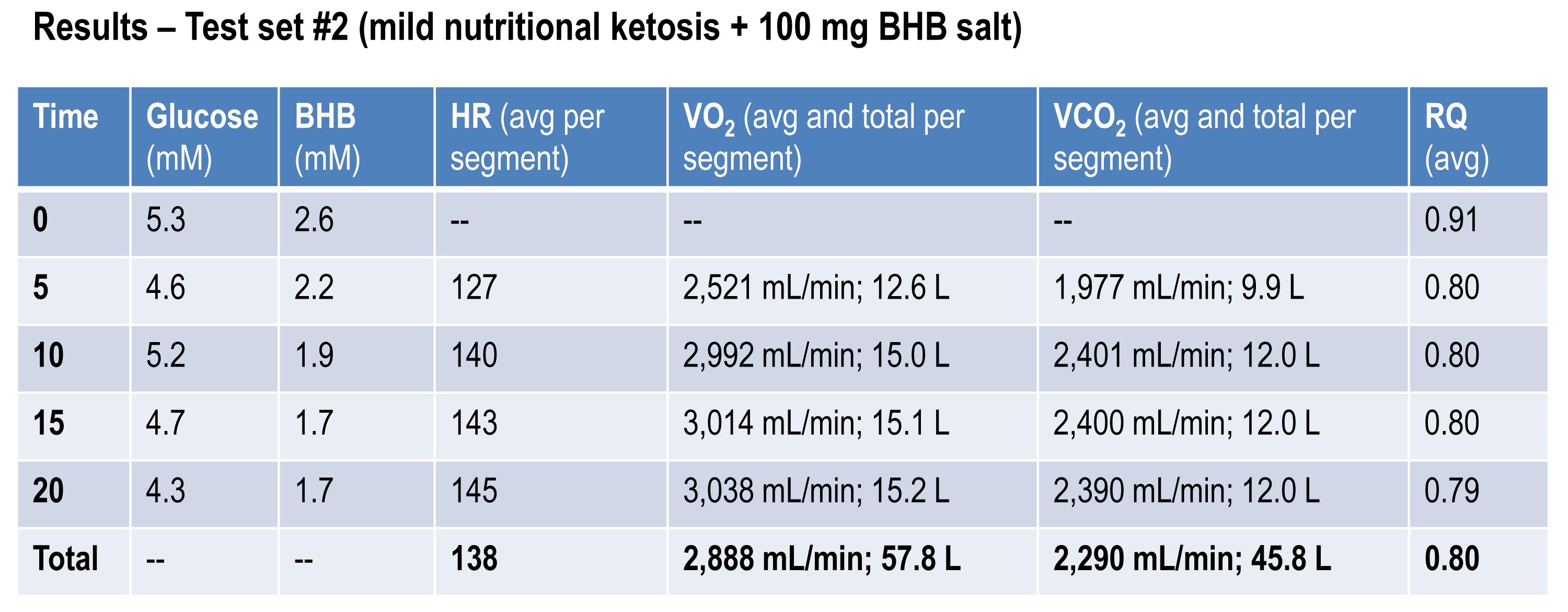

Test set #2 (ingestion of 15.6 g BHB salt 60 minutes prior)

The table below shows the same measurements and calculations as the above table, but under the test conditions. You’ll note that BHB is higher at the start and falls more rapidly, as does glucose (for reasons I’ll explain below). HR data are almost identical to the control test, but VO2 and VCO2 are both lower. RQ, however, is slightly higher, implying that the reduction in oxygen consumption was greater than the reduction in carbon dioxide production.

If you do the same calculations as I did above for estimating fat oxidation, you’ll see that EE in this case was approximately 13.92 kcal/min, while fat oxidation was only 67% of this, or 9.28 kcal/min, or 1.03 g/min. So, for this second effort (the test set) my body did about 5% less mechanical work, while oxidizing about 25% less of my own fat. The majority of this difference, I assume, is from the utilization of the exogenous BHB, and not glucose (again, I will address below what I think is happening with glucose levels).

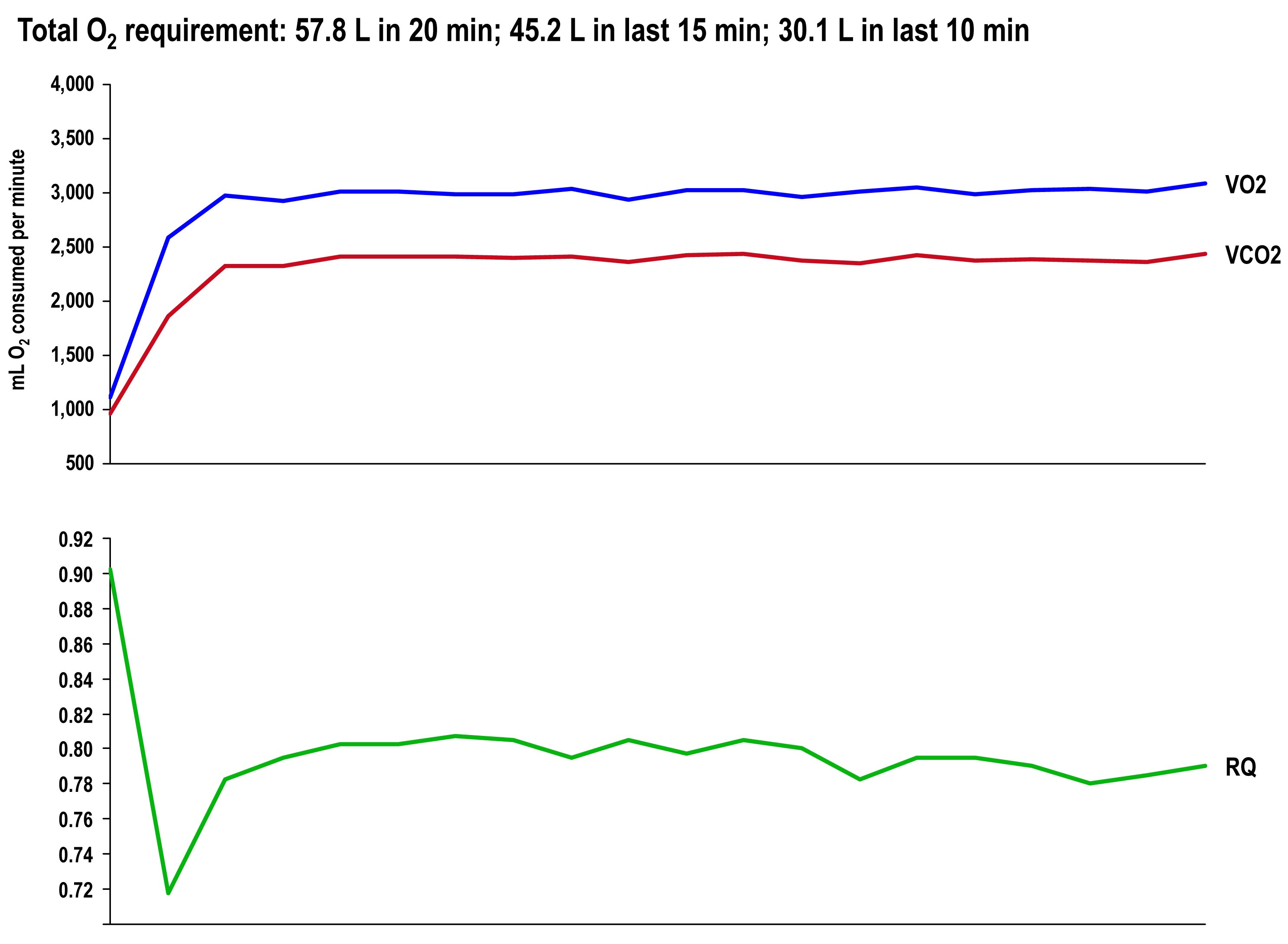

The graph once again shows the continuous data for VO2, VCO2 (measured), and RQ (calculated).

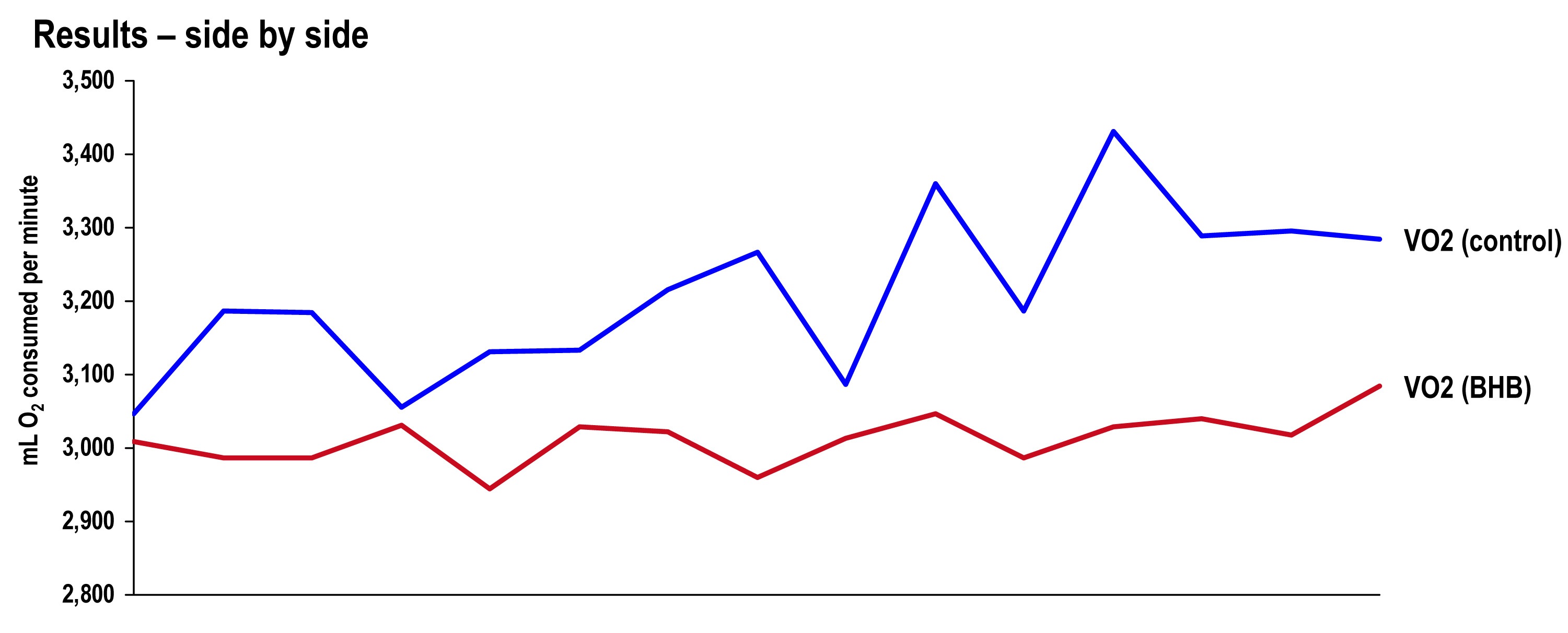

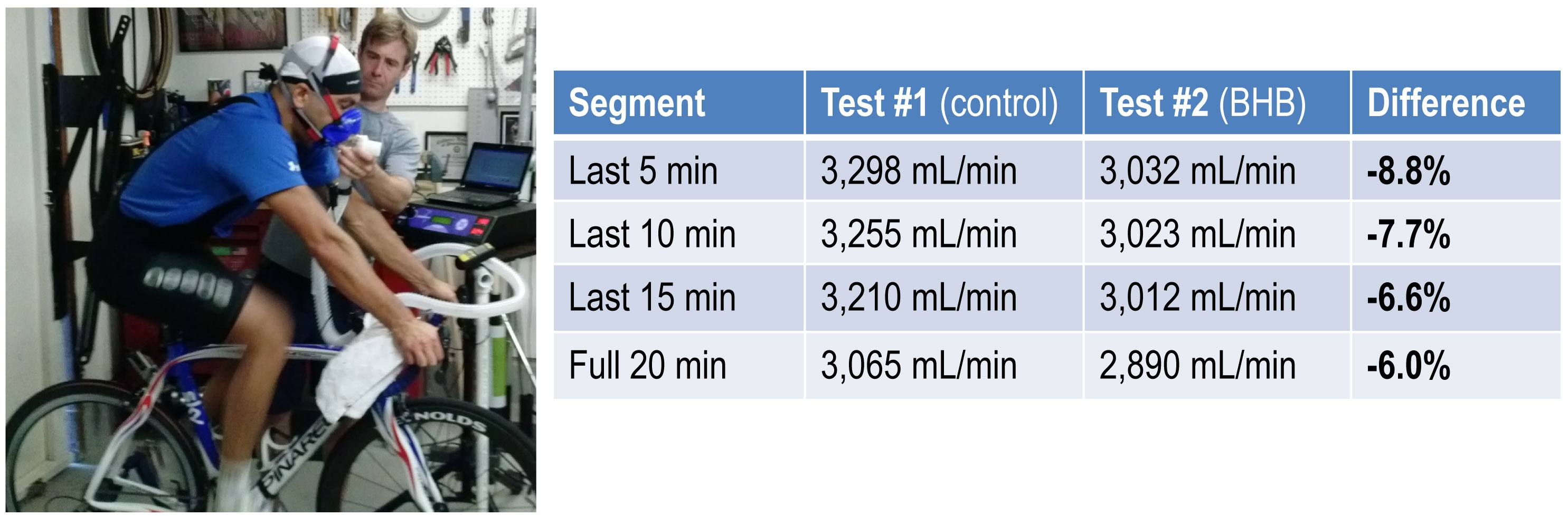

Side-by-side difference

The final graph, below, shows the continuous data for only VO2 side-by-side for the 20 minute period. The upper (blue) line represents oxygen consumption under control conditions, while the lower line (red) represents oxygen consumption following the BHB ingestion. In theory, given that the same load was being overcome, and the same amount of mechanical work was being done, these lines should be identical.

The hypothesis being tested in this “experiment” is that they would not be the same. Beyond visual inspection, the difference between the lines appears to grow as the test goes on, which is captured in the tabular data showing 5 minute segmental data.

Limitations

The most obvious limitation of this endeavor is the fact that it’s not an appropriately controlled experiment. Putting that aside, I want to focus on the nuanced limitations—which don’t impact the primary outcome of oxygen consumption—even if one were appropriately doing a real experiment.

- It’s not clear that the Weir coefficients used to estimate EE are relevant for someone in ketosis, let alone someone ingesting exogenous BHB. (The Weir formula states that EE is approximated by 3.94 * VO2 + 1.11 * VCO2, where VO2 and VCO2 are measured in L/min; 3.94 and 1.11 are the Weir coefficients, and they are derived by tabulating the stoichiometry of lipid synthesis and oxidation of fat and glucose and calculating the amount of oxygen consumed and carbon dioxide generated.) While this doesn’t impact the main observation—less oxygen was consumed with higher ketones—it does impact the estimation of EE and substrate use.

- In addition to the Weir coefficients being potentially off (which impacts EE), the RQ interpretation may be incorrect in the presence of endogenous or exogenous ketones. As a result, the estimation of fat and glucose oxidation may be off (though it’s directionally correct). That said, the current interpretation seems quite plausible—greater fat oxidation when I had to make my ketones; less when I got my ketones for “free.”

Observations from this “experiment” (and my experience, in general)

Animal models (e.g., using rat hearts) and unpublished case reports in elite athletes suggest supplemented BHB produces more ATP per unit carbon and per unit oxygen consumed than glycogen and FFA. This appears to have been the case in my anecdotal exercise.

The energy necessary to perform the mechanical work did not appear to change much between tests, though the amount of oxygen utilization and fat oxidation did go down measurably. The latter finding is not surprising since the body was not sitting on an abundant and available source of BHB—there was less need to make BHB “the old fashioned way.”

As seen in this exercise, glucose tends to fall quite precipitously following exogenous ketone ingestions. Without exception, every time I ingested these compounds (which I’ve probably done a total of 25 to 30 times), my glucose would fall, sometimes as low as 3 mM (just below 60 mg/dL). Despite this, I never felt symptomatic from hypoglycemia. Richard Veech (NIH) one of the pioneers of exogenous ketones, has suggested this phenomenon is the result of the ketones activating pyruvate dehydogenase (PDH), which enhances insulin-mediated glucose uptake. (At some point I will also write a post on Alzheimer’s disease, which almost always involves sluggish PDH activity —in animal models acute bolus of insulin transiently improves symptoms and administration of exogenous ketones does the same, even without glucose.)

In addition, the body regulates ketone production via ketonuria (peeing out excess ketones) and ketone-induced insulin release, which shuts off hepatic ketogenesis (the liver making more ketones when you have enough). The insulin from this process could be increasing glucose disposal which, when coupled with PDH activation, could drive glucose levels quite low.

If that explains the hypoglycemia, it would seem the absence of symptoms can be explained by the work of George Cahill (back in the day; see bottom figure in this post)—when ketone levels are high enough they can dominate brain fuel, even ahead of glucose.

Finally, these compounds seemed to have a profound impact on my appetite (they produced a strong tendency towards appetite suppression). I think there are at least two good explanations for this, which I plan to write about in a dedicated post. This particular topic—appetite regulation—is too interesting to warrant anything less.

Open questions to be tested in real experiments

- Are these results reproducible? If so, how variable are the results across individuals (by baseline metabolic state, diet, fitness)?

- Would the difference in oxygen consumption be larger (or smaller) in an athlete not already keto-adapted (i.e., not producing endogenous ketones)?

- Would the observed effect be greater at higher plasma levels of BHB (e.g., 5 to 7 mM), which is “easily” achievable with exogenous ketones?

- Would the observed effect be the same or different at higher levels of ATP demand (e.g., at FTP or at 85-95% of VO2 max)?

- Would the trend towards improved energy efficiency continue if the exercise bout was longer in duration (say, greater than 2 hours)?

- How will exogenous ketones impact exercise duration and lactate buffering?

- Why do exogenous ketones (both BHB and AcAc it seems) reduce blood glucose levels so much, and can this feature be exploited to treat type 2 diabetes?

- Are there deleterious effects from using exogenous ketones, besides GI side-effects?

- What are the differences between exogenous BHB and AcAc (which in vivo exist in a reversible equilibrium) on this particular phenomenon? (Work by Dom D’Agostino’s group and others have shown other differences in metabolic response and clinical application, including their relative impact on neurons.)

Photo by Alexey Lin on Unsplash

378 Comments