One of the questions I most often receive: Does being in ketosis automatically translate to fat loss?

For those too busy to read ahead, let me give you the punch line: No. For those who want to understand why, keep reading (hopefully this is still everyone). This topic is — surprise, surprise — very nuanced, and almost always bastardized when oversimplified, which I’m about to do, though hopefully less than most. Without oversimplifying, though, this will turn into a textbook of 1,000 pages.

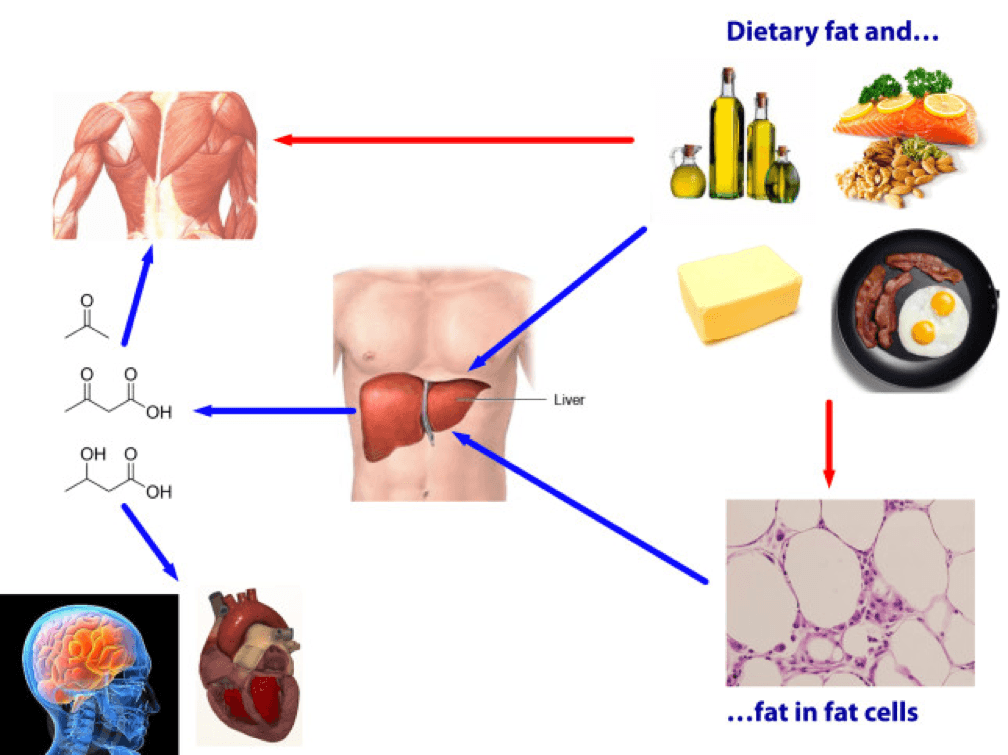

From the ketosis series, or at least the first and second part, along with the video in this previous post, you should have taken away that ketosis is not some ‘magical state of mystery.’ It’s simply a state of physiology where our liver turns fatty acid (both ingested and stored) into ketones.

There seems to be great confusion around ‘nutritional’ ketosis (a term we use to distinguish ‘dietary-induced’ ketosis from the other 2 forms of ketosis: starvation ketosis and ketoacidosis, the latter a serious complication of type I diabetes). But, before I try to dispel any of the confusion, we need to go through a little primer on what I like to call “fat flux.”

One point before diving in, please do not assume because I’m writing this post that I think adiposity (the technical term for relative amount of fat in the body) is the most important thing to worry about. On the contrary, I think the metabolic state of the cell is far more important. While there is a correlation between high adiposity (excessive fat) and metabolic dysfunction, that correlation is far from perfect, and, as I’ve discussed elsewhere, I think the arrow of causation goes from metabolic dysfunction to adiposity, not the reverse. But, everyone wants to lose fat, it seems, so let’s at least get the facts straight.

Let’s start with an assertion: Barring the presence of scientific evidence I’m unaware of, and barring surgical intervention (e.g., liposuction), reducing the adiposity of a person is achieved by reducing the adiposity of individual adipose cells, collectively. In other words, the number of adipocytes (fat cells) we have as an adult does not change nearly as much as their size and fat content. So, for people to reduce their fat mass, their fat cells must collectively lose fat mass.

Fat flux 101

According to “An Etymological Dictionary of Modern English,” the word flux comes from the Latin word fluxus and fluere, which mean “flow” and “to flow,” respectively. While the term has a clear mathematical meaning in physics, defined by a dot product I promise I won’t speak of, you can think of flux as the net throughput which takes into account positive and negative accumulation.

If we start with a bucket of water and put a hole in the bottom, the result, needless to say, is an efflux of water, or negative water flux. Conversely, if we start with a bucket – no hole – and we pour water in, that’s an influx of water, or positive water flux.

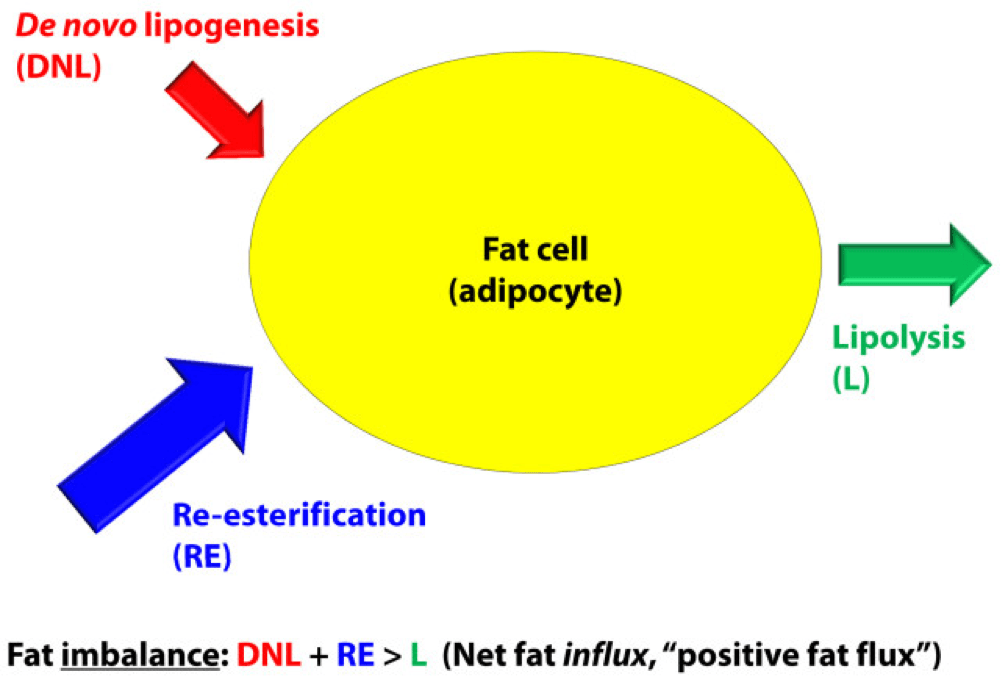

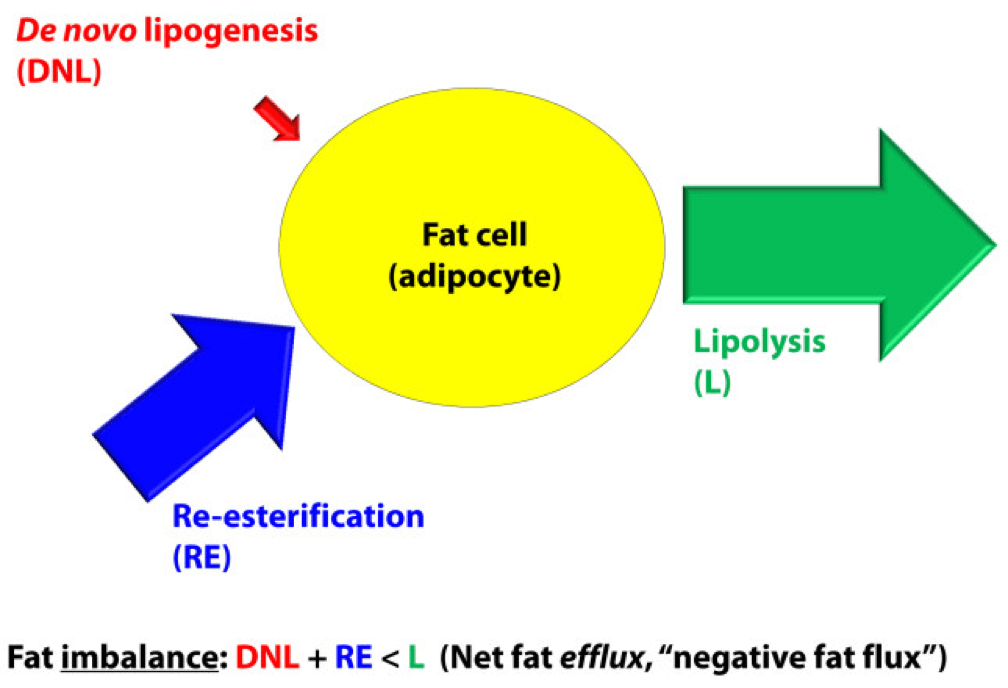

If that makes sense, then the idea of fat flux is pretty straight forward. If more fat enters a fat cell (called an adipocyte) than leaves it, the fat cell is experiencing a net influx – i.e., positive fat flux. And, if more fat leaves a fat cell than enters, the reverse is true: it is experiencing a net efflux, or negative fat flux.

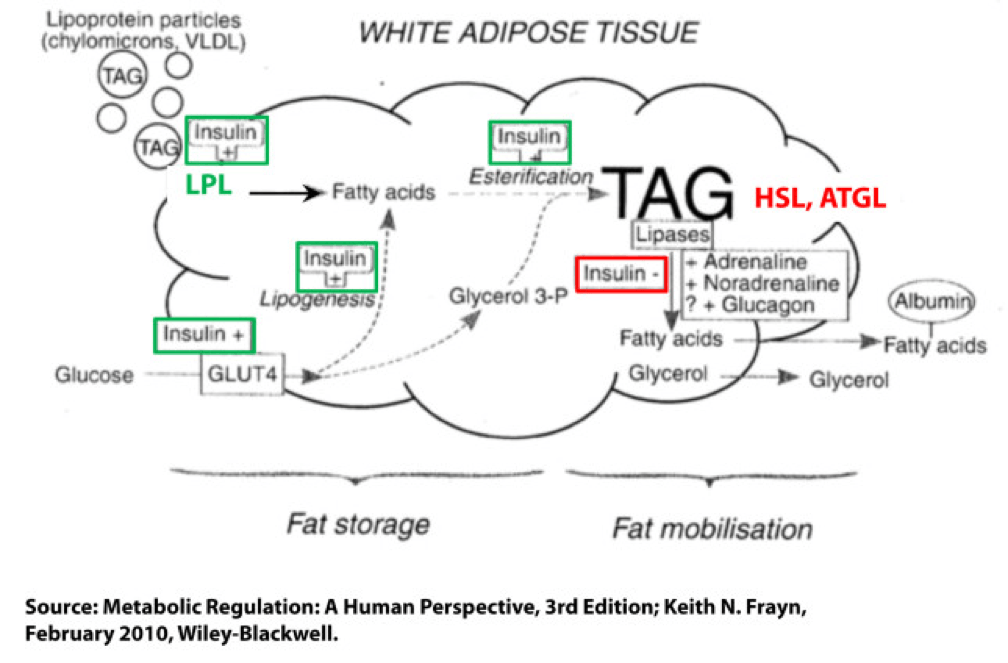

Not surprisingly, a fat cell is more complicated than a bucket. Basically, though, there are two “inputs” and one “output.” The figure below shows this in some detail. (TAG stands for triacylglycerol, which is another word for triglyceride, which is the storage form of fat.) The first thing you may appreciate, especially since I’ve highlighted it, is the role insulin plays in regulating the process of fat flux. Insulin does the following:

- Upregulates lipoprotein lipase (LPL), an enzyme that breaks down TAG so they can be transported across cell membranes. Since TAG are too big to bring across cell membranes, they need to be “hydrolyzed” first into free fatty acids, then re-assembled (re-esterified) back into TAG.

- Translocates GLUT4 transporters to the plasma membrane from endosomes within the cell. In other words, insulin moves the GLUT4 transporter to the cell surface to bring glucose into the cell.

- Facilitates lipogenesis, that is, facilitates the conversion of glucose into acetyl CoA which gets assembled into fatty acids along with glycerol.

- Facilitates esterification, that is, facilitates the process of assembling fatty acids into TAG (3 fatty acids per TAG).

- Inhibits hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) and adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), two important enzymes that breaks down TAG into fatty acids and glycerol such that the fatty acids can be released from the fat cell. Once bound to albumin the free fatty acids are free to travel elsewhere in the body for use (e.g., to the liver for conversion to ketones, to the heart muscle or skeletal muscles for conversion to ATP).

- Though not shown in this figure, insulin appears to indirectly act on malonyl-CoA, a potent inhibitor of CPT I, one of the most important mitochondrial enzymes that facilitates the oxidation of fatty acids. (CPT I is what enables fatty acids to be shuttled into the mitochondria for oxidation, the process which releases or liberates their energy through electron transport.)

Other hormones and enzymes in the body also play a role. For example, under a sympathetic response, the so-called “fight or flight” response, adrenaline and noradrenaline (i.e., epinephrine and norepinephrine) activate HSL and ATGL to combat the effect of insulin as an inhibitor of lipolysis, thereby increasing lipolysis, or liberating stored energy from the fat cell. Glucagon may also play a role in this process, though the exact role is not as well understood, at least not in humans.

So in summary, insulin is indeed the master hormone that regulates the flow of fat (and glucose) into and out of a fat cell. There are other players in this game, to be sure, but insulin is The General. High levels of insulin promote fat storage and inhibit fat oxidation, and low levels of insulin promote fat mobilization or release along with fat oxidation.

If this sounds crazy – the notion that insulin plays such a crucial role in fat tissue — consider the following two clinical extremes: type 1 diabetes (T1D) and insulinoma. In the former, the immune system destroys beta-cells (the pancreatic cells that make insulin) – this is an extreme case of low insulin. In the case of the latter, a tumor of the beta-cell leads to hypersecretion of insulin – this is an extreme case of high insulin. Prior to the discovery of insulin as the only treatment, patients who developed T1D would become emaciated, if the other complications of glycosuria and dehydration didn’t harm them first. They literally lost all fat and muscle. Conversely, patients with insulinoma often present looking not just obese, but almost disfigured in their adiposity. Because Johns Hopkins is a high-volume referral center for pancreatic surgery, it was not uncommon to see patients with insulinoma when I was there. As quickly as we would remove these tumors, the patients would begin to return to their previous state and the adipose tissue would melt away.

For the purpose of our discussion, I’ve simplified the more detailed figure above into this simplified figure, below. I’ve tried to size the arrows accordingly to match their relative contributions of each input and output.

The first figure, below, shows a state of fat balance, or zero net fat flux.

Input #1: De novo lipogenesis, or “DNL” – Until the early 1990’s there was no way to measure this directly, and so no one really had any idea how much this process (i.e., the conversion of glucose to fat) contributed to overall fat balance. Without going into great technical detail, , arguably one of the world’s foremost authorities on metabolomics and DNL, developed a tracer technique to directly measure this process. If I recall correctly, the original report was in 1991, but this paper is a great summary. Published in 1995 in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, this paper would go on to become the “citation classic.” This study demonstrated that under eucaloric feeding conditions, with about 50% of energy coming from CHO, DNL did not represent a significant contribution to fat flux. It was about 5%, hence the tiny red arrow under a state of fat balance (i.e., a state where fat entering the fat cell is equal to fat leaving the fat cell). A very important point to be mindful of, however, is this: this represents an average throughout the body and does not differentiate specifically between, say, DNL in the liver and DNL in the periphery (i.e., fat cells). This limitation is not trivial, but rather than focus on the very specific details of this paper, I’d rather use it as a framework for this discussion. (This paper is really interesting, and were it not for the fact that this post is going to be long enough, I would say much more about it. As such, I will probably do a full post on this paper and related topic in the future. The 1995 paper also examined what happened to DNL during periods of over- and under-feeding CHO and fat.)

Input #2: Re-esterification, or “RE” – In a state of fat balance, RE is largely composed of dietary fat sources that are not immediately used, but rather stored for later use. (Nuanced point: RE also includes fatty acids that were previously liberated from adipocytes, not oxidized, and are now being recycled back into TAG. This is a normal consequence of fat liberation. The fat cell probably ‘deliberately overdoes it’ by liberating more fatty acid from TAG just to be safe; that which is not oxidized is re-esterified. The exact balance of RE composed from dietary sources versus recycled fatty acids will depend on fat consumption and energy demands of the person. For the purpose of simplicity, this diagram does not show some portion of the L fraction returning to the RE fraction, though this is exactly what is happening in ‘real life.’)

Obviously, though, the relative size of the blue arrow depends on how much fat one is consuming and how many metabolic demands are in place for fatty acids. The latter is highly determined by dietary composition (see the discussion on RQ, or respiratory quotient, at about minute 31 in this video).

For the real aficionado, there is another wee bit of nuance here. This study, published in 1991 in the Journal of Lipid Research, suggested that the RE process is a bit more complicated than simply re-assembling fatty acids on a glycerol backbone inside an adipocyte. Based on these experiments, which used a similar* tracer method to the one used by Hellerstein et al. to evaluate DNL, the authors (which included Rudy Leibel, the co-discoverer of leptin) suggested that RE requires an intermediate step outside of the adipocyte in the interstitial and capillary space (figure 8 of the paper demonstrates this very well schematically).

(*) Technically, Hellerstein et al. used a heavy isotope; Leibel et al. used radioactive isotopes.

Output: Lipolysis, or “L” – Finally, in a state of fat balance, lipolysis must be equal to the sum of DNL and RE. This is true if we are talking about tiny little fat cells or giant ones. Remember, it’s the balance that matters.

I hope it’s clear from this summary that there are an infinite number of physiologic states that can satisfy the equation of fat balance: DNL + RE = L. For example, someone like me who is in fat balance (i.e., I’m neither gaining nor losing fat mass at this point) on a ketogenic diet with daily fat intake often exceeding 400 grams, has virtually zero DNL, but quite high RE, especially after meals. Consequently, I have very high L. If you took a person on a very low-fat diet (e.g., 20% fat, but 65% CHO), they would have modest DNL and low RE, but they would have low L. We would both be in fat balance, but we satisfy the equation DNL + RE = L by very different means.

OK, so let’s turn our attention to the non-equilibrium states: Net fat influx and net fat efflux.

Fat influx

In a state of net fat influx – accumulation of fat within a fat cell – the following condition must be met (on average): DNL + RE > L. (I say “on average” because, of course, a fat cell is a dynamic system with constant changes in these parameters. So, at any moment in time the balance can shift, but over a period of time the equation is correct.)

The next (overly simplistic) figure below gives you a representative state of what fat influx or ‘positive fat flux’ probably looks like. DNL is higher, but still relatively small, unless overfeeding CHO. RE is larger than it was in a balanced state, but not necessarily ‘huge.’ Most cases of net fat influx are probably governed by low L. In other words, fat accumulation is probably more governed by a failure to mobilize (breakdown TG into fatty acids for export and use) TAG than anything else.

Have you ever spoken with someone who is trying desperately to lose weight (fat) who says, “I don’t understand what’s happening…I hardly eat any fat, and yet I can’t lose a pound (of fat)!” The skinny people in the group scoff, right? Well, not so fast. It’s quite possible, if the hormones that regulate fat tissue are not working in your favor, to do such a poor job mobilizing fat from fat cells, and oxidizing that fat (see below), that you can be in fat balance, or even fat imbalance with accumulation, despite small DNL and small RE.

If you think about it, lipolysis (L), or liberating fat from a fat cell is a necessary, but not sufficient condition to actually generate the free energy inherent or stored within it. One more major step is necessary – oxidizing the fatty acid via the process of beta-oxidation. This is where one actually gets the energy (ATP) from fatty acids. The same hormones and enzymes that promote L, directly or indirectly act on other intermediaries that promote oxidation, more or less. The converse is also largely true.

Brief digression: I’m always troubled by folks who have never tried to take care of someone who is struggling to lose weight (fat), and who themselves have never been overweight, but who insist obesity is ‘simply’ an energy balance problem – people eat too many calories. When eternally lean people preach about the virtues of their ‘obvious’ solutions to obesity – just eat less and exercise more – I’m reminded of a quote (source unknown to me), “He was born on the finish line, so he thinks he won the race.” You only need to meet one woman with PCOS, or one person with hypothyroidism, or one child with Cushing’s disease to know that adiposity can – and is – largely regulated by hormones. The fact that such patients need to create a positive energy balance (i.e., eat more calories than they expend) to allow it does not seem to provide a meaningful insight into the mechanism of why.

Fat efflux

In a state of net fat efflux – reduction of fat within a fat cell – the following condition must be met (on average): DNL + RE < L (same caveat as above on the idea of “on average”). Again, looking at the figure, you can see one physiologically common way this occurs, the setting of carbohydrate restriction. DNL is reduced (probably even to immeasurable levels, depending on the extent of restriction), but RE actually goes up. The net efflux, however, results from the greater increase in L.

A person in nutritional ketosis, if experiencing fat loss, probably looks like this. (Don’t worry, I have not forgot the opening questions: Does being in nutritional ketosis automatically put you in this state?). Certainly another state of net fat efflux is starvation. DNL and RE are both very small, especially DNL, and lipolysis is quite large. This is probably the most rapid state of negative fat flux a human can experience.

So what we do about it?

I do not believe there is only one state, shy of total starvation, which will assuredly put you in state of negative fat flux. Of course, starvation is not sustainable, and therefore should be taken off the table as a viable long term eating strategy.

What about profound caloric restriction? Yup, this is probably (though not necessarily) going to work, depending on how “profound” is defined. If defined as a 40% reduction of energy stable intake, it’s probably going to work. If defined as a 10% reduction, it would be difficult to know without knowing at least two other things:

- Baseline level of insulin resistance;

- RQ of pre- and post-diet.

What about dramatic alterations in macronutrient composition? This is where the discussion gets really interesting. Many people, myself included, advocate a diet that overall reduces insulin secretion. The rationale, of course, is provided by the first figure above (from the textbook) and a slew of clinical studies which I will not review here (see Gardner JAMA 2007, Ludwig JAMA 2012, and Shai NEJM 2008 to name a few).

But, the bigger question is why? Why do most (but not all, by the way) people with excess fat to spare who are on well-formulated carbohydrate-reduced diets lose fat? (Notice, I did not say weight, because the initial – and often rapid — weight loss achieved by many is actually water loss.)

Is it because of a physiologic change that leads them to reduce overall intake?

Is it because of a physiologic change that, despite the same intake in overall calories, increases their energy expenditure?

Is it some combination of these?

I wish I knew the answer, but I don’t (universally). I believe we will know the answer to this question in a few years, but until then, I’m left to offer the best my limited intuition can offer. In other words, what I suggest below is my best interpretation of the literature, my personal experience that I’ve had with hundreds of other people, and my discussions with some of the most thoughtful scientists in the world on this topic:

Thought #1: I suspect that many people who reduce simple carbohydrates and sugars end up eating fewer calories. This observation, however, may confound our understanding of why they lose weight. Do they lose weight because they eat less? Or, do they eat less because they are losing weight? I suspect the later. In this state, lipolysis — and by extension, given the hormonal milieu, oxidation — are very high, certainly relative to their previous state. By definition, L > DNL + RE, so there is ample ATP generated by oxidation of the fatty acid. If you believe (as I do*) that the liver is the master organ of appetite regulation, increases in ‘available energy’ (i.e., ATP) would naturally reduce appetite (though I don’t think we know if ATP per se is the driver of this feedback loop). But don’t confuse what’s happening. They are not giving up fat from their fat cells because they are eating less. They are eating less because they are giving up fat from their fat cells. Big difference.

(*) The especially astute reader will note that this is the first time I have made reference to this point. I have been heavily influenced recently by the work of Mark Friedman, and a discussion of this point is worth an entire post, which I promise to deliver at some point in the future. If you can’t wait, which I can understand, I highly encourage you to start scouring the literature for Mark’s work. It’s simply remarkable.

Thought #2: I also suspect that some fraction of people who follow this eating strategy lose fat without any appreciable reduction in their total caloric intake, at least initially. What?, you say, doesn’t this violate the First Law of Thermodynamics? Not at all. If L > DNL + RE, and the increase in lipolysis (i.e., fatty acid flux out of the fat cell) results in increased oxidation of fatty acids, energy expenditure (EE) would be expected to rise. A rise in EE, in the face of constant input, is a sign of fat loss. What differentiates those in this camp (I was in this camp) from those above (point #1), is unclear to me. It may have to do with concomitant exercise. I have seen unpublished data, which I can’t share, suggesting non-deliberate EE rises more in a low RQ (high fat, low carb) environment when a person is exercising significantly. I’m not stating the obvious – that the deliberate EE is higher – that is clearly true. I’m suggesting resting EE is for some reason more likely to rise in this setting. Since I’m taking the liberty of hypothesizing, I would guess this effect (if real) is a result of the body trying to keep up with a higher energy demand and making one trade-off (generating more free ATP via more lipolysis) for another (ensuring a constant supply of available energy to meet frequent demands). It is also possible that this increase in free/available energy results in an increase in deliberate EE (i.e., the person who suddenly, in the presence of a cleaned up diet feels the desire to walk up the stairs when they previously took the elevator). Finally, and perhaps most importantly, whether or not this up-regulation of energy takes place may be dependent on the other hormones in the body that also play a role in fat regulation, including cortisol, testosterone, and estrogen. They could be partly or mostly responsible for this. The literature is quite dilute with respect to this question, but in my experience (feel free to dismiss), it is not uncommon to see a reduction in cortisol and an increase in testosterone (I experienced about 50% in free and total testosterone) with a dietary shift that improves food quality. The same may be true of estrogen in women, by the way, though I have less clinical experience with estrogen.

Thought #3: As a subset to the point above (point #2), in an ‘extreme’ state of carbohydrate restriction, i.e., — nutritional ketosis — there is an energy cost of making the ketones from fatty acids. I referred to this as the “Hall Paradox” after Kevin Hall, who first alerted me to this, in this post (near the bottom of the post). What is not clear (to me, at least) is if this effect is transient and if so, how significant it is. I recall that during the first three months of my foray into nutritional ketosis, I was eating between 4,000 and 4,500 kcal/day for a 12-week period, yet my weight reduced from 176 lb (about 9.5% bf by DEXA) to 171 lb (about 7.5% bf by DEXA), which means that of the 5 pounds I lost in 12 weeks, 4 were fat tissue. Today, however, I don’t consume this much, closer to 3,800 kcal/day, and one reason may be that two years later my body is more efficient at making ketones and this so-called “metabolic advantage” is no longer present.

(I have always found the term “metabolic advantage” to be misleading, though I’m guilty of using it periodically. It’s really a metabolic disadvantage if your body requires more energy to do the same work, but nevertheless, people refer to – and argue vehemently about – this phenomenon. The question is not, does it exist? One look at individual summary data from David Ludwig’s JAMA paper on this topic makes that clear. The questions are, why does it only exist in some people, what relevance does it have to fat loss – is it cause or effect? – and, for how long does it persist?)

Thought #4: For reasons I have yet to fully understand, some people can only lose fat on a diet that restricts fat (and by extension a diet that is still high in carbohydrate, since I’m excluding starvation and profound caloric restriction from this discussion). In my experience (and Gardner’s A TO Z trial seems to validate this, at least in pre-menopausal women), about 20% of people aspiring to reduce adiposity seem to do it better in a higher RQ environment. Using the Ornish diet as the example from this paper, I suspect the reason is multifactorial. For example, the Ornish diet restricts many things, besides fat. It restricts sugar, flour, and processed carbohydrates. Much of the carbohydrate in this diet is very low in glycemic index and comes primarily from vegetables. So, I don’t really know how likely it is to lose weight on a eucaloric diet that is 60% CHO and 20% fat, if the quality of the carbohydrates is very poor (e.g., cookies, potato chips). The big confounder in these observations is that most low-fat diets, though still modestly high in RQ relative to a low-carb diet, reduce greatly the glycemic index and glycemic load, as well as the fructose.

Which brings us to the point…

Does being in nutritional ketosis ensure negative fat flux (i.e., fat loss, or L > DNL + RE)?

Being in ketosis tells us nothing about this equation! Let me repeat this: It is metaphysically impossible to infer from a measurement of B-OHB in the blood if this equation is being satisfied. It just tells us that our body is using some fraction of our dietary fat and stored fat (once it undergoes lipolysis) to make ketones, given that glucose intake is very low and protein intake is modest (net effect = minimal insulin secretion).

If you look at the figure below, you see this point (It’s simplified, obviously, and for example, does not show that fat from fat cells can be used directly by skeletal muscles). Nothing in this figure implies a reduction in the size of the cells at the bottom right of the figure. It’s quite possible, of course, since ketosis results in a large L and implies a very small DNL. But, if (small) DNL + (very large) RE is greater than (large) L, guess what? Fat flux is net positive. Fat is gained, not lost. Still in ketosis, by the way (quantified loosely by fasting levels of B-OHB greater than about 0.5 to 1 mM), but not losing fat. (I hope the first attempt at a solution in this setting is obvious by now, notwithstanding the fact that I’ve seen this situation dozens of times with more than one solution, including the ‘obvious’ one — reducing fat intake.)

The other myth worth addressing is that the higher the level of B-OHB, the more “fat burning” that is going on. This is not necessarily true at all. As you can tell, I love equations, so consider this one:

B-OHB (measured in blood) = B-OHB produced (from dietary fat) plus B-OHB produced (from lipolysis of TAG) less B-OHB consumed by working muscles, heart, brain.

How does knowing one of these numbers (B-OHB measured in blood) give definitive answers to another (B-OHB produced from lipolysis of TAG)? It can’t. That’s the problem with multivariate algebra (and physiology).

Many people who enter nutritional ketosis do so, I worry, because they believe it “guarantees” fat loss. I hope I have convinced you that this is not true. Nutritional ketosis is one eating strategy to facilitate negative fat flux, and it works very well if done correctly. It comes with some advantages and some disadvantages, just like other eating strategies. When I get back to the series on ketosis, I will address these, but for now I felt it was very important to put things in perspective a bit. Furthermore, I am convinced that it is not the ideal eating strategy for everyone.

Delorean by Marci Maleski is licensed under CC by 2.0

Peter thank you for this blog. I found you through your recent Ted talk. I am a 36 yo female c PCOS who has been on Metformin for 16 years. I maintain a BMI between 20-22, I have the easiest time losing or maintaining weight when I do not exercise and stay on a low CHO diet. However, I love to exercise and I find it frustrating that I always gain fat. My question is, do you have an opinion of how the Metformin may be influencing my metabolism when I am exercising (moderate to high intensity for 50 min 4-5x wk)? The Metformin has yielded reductions in my androgen levels, but I am curious now that I have altered my intake of CHO and/or exercise regularly, if the Metformin may be working against me. Thank you for any thoughts you may have.

Very interesting, Anne. If the exercise is vigorous, it may be that the inhibition of hepatic glucose output (metformin’s mechanism of action) is interfering with your liver’s ability to detect adequate ATP, which could drive up appetite?

Note: I neglected to mention that I am not diabetic.

Dr. A –

I recently made a comment to you – (I’m the one who was an altruistic kidney donor) – anyways…I just want you to know that you speak so far over my head and I love it! I really do…it challenges me to think far beyond what I’ve ever been challenged to do.

Thank you….You are making a huge difference…just by speaking and writing. Thank you! You are bright and I appreciate it.

Teresa

I showed a friend this post a few days ago, before posting it. He said, “Why the hell would you write to so much and in such a technical manner? More people would read your blog if you kept it to 500 words and dumbed it down!”

To which I responded:

1. My goal has never been “readership” — I’d rather a few readers who can really diggest than countless who will forget it tomorrow.

2. The folks who read this blog are self-selecting on intellectual curiosity and passion for this topic

3. I appreciate your feedback, but I think I’ll keep it as-is.

Dear Peter

I have read almost all your posts in the past two weeks after I first heard your Tedtalk. I appreciate the mission of your amazing organisation and obsession with being fitter and removing the food fallacies that plague our generation and beyond. I started my first dietary intervention in Oct 2012 with Dukan- switching to pure lean protein and veggies on alternate days. Having been a vegetarian in first 26 years of my grain laden diet..i found the results pretty encouraging with literally melting away of the body fat, increase in core strength, energy levels, an inherent needl to be physically more active and try out stuff i never wanted to do before. I lost 7 kilos in weight and 3 inches around my waist. My BMI now is 21. After reading your blog I upped the healthy fats and tried ketosis for the last 2 weeks. After an initial further loss in the inches i seemed to backtrack a bit. I was questioning if maybe the fat inflow now was more than the lipolysis and therefore I was probably storing more triglycerides than i was burning while earlier on dukan i was only burning the body fat and so had a net negative on fat equation. That’s when this post came. Does this mean than when attempting to lose body fat via ketosis you need to watch not just relative food percetages but also the total food consumed..sounds like counting calories again. The other bit is in one of your posts where they studied effects of different dietary interventions on a sample of people some people responded better to low GI or even low fat diets. Do you think dukan which is a low GI, low fat diet may work better atleast in some cases to induce nutritional ketosis that has bulk of B-OHB coming from fat deposits rather than dietary fat. Having said this what does intrigue me is the a access to the 100,000 calorie fat reserve in the body that you can possibly unlock on a high fat diet…would this happen even on lean protein low GI diet?

Thank you

It could still happen, as long as insulin levels, on average, are quite low, though probably not quite as effectively (unless the diet was very hypocaloric).

Dr Attia

Is it possible to go into nutritional ketosis on a vegetarian diet. What vegetarian supplements would you reccomend in this scenario where you would burn body fat while retaining healthy lean mass?

Thank you so much for your response and sharing your knowledge.

Yes it’s possible, but more work involved, especially for very active people. For sedentary folks consuming relatively little it’s easier.

Dear Dr. Attia,

Thank you so much for your blog.

I read this article by an Australian doctor on obesity this spring: https://www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2013/march/1361848247/karen-hitchcock/fat-city

and it kind of haunted me. The 700 comments more so.

The antithesis and antidote was your TED talk.

In a moment of congruence I was diagnosed as insulin resistant and given a 650 cal ketogenic diet (from the leading obesity doctor in Belgium via a university hospital) and told many things contrary to your site: eat low fat, use fake sweeteners, avoid salt, no nuts. While I’ve lost weight 16lbs/7.2kgs in about a month, I have suffered with zero stamina, probably feeling much like you felt in the beginning of your 12 week experiment. I’ve been adding more bouillon cubes and coconut oil and hopeful for improvements.

It was info that was somewhat tricky to root around and find on your site, as the navigation/organization is tricky in terms of locating, and sometimes processing (I’m definitely an intellectual but of the liberal arts/social sci variety — in other words no hard or med science background) information, I am still grateful for your labor of love and the fact that you don’t dumb down your writing. And see fit to intersperse your discoveries with potent reminders about humanity, like the story about Woody Sparrow.

Again, thanks for your blog.

Justine, I read this, also, a while back. Needless to say, I think the smugness of this author is deplorable. Think of the quote I referenced in this post, “She was born on the finish line, so she thinks she won the race.” I would be willing to bet she doesn’t take care of too many people suffering from the diseases associated with obesity.

I have no response to such people and instead I choose to do what I do. Let them do what they do.

Last comment: is it nearly impossible to undergo a low-salt KD. That would be the first place I would suspect your weakness is coming from. Pick up a copy of Jeff Volek & Steve Phinney’s book “The Art & Science of LC living.” Great “how to” guide on ketosis.

I can’t claim to understand this article completely, but I gleaned enough to help me see why I don’t seem to get the same results on KD as my spouse, though we are both in our sixties, and reasonably active. I find that I still have cravings, which he says are non-existent for him. I am low normal thyroid which I believe may be a factor.

Nan, correction of hypothyroidism can definitely “unleash” your lipolysis potential.

Great post Peter (enhanced by flux capacitor reference), good balance between giving us enough without losing everyone and also providing enough of the answers without speculating into areas NUSI may look to research.

I have still to soak it in properly but I wondered if you could please help my simple brain by considering this dumb question. Although a state of Nutritional Ketosis does not guarantee fat loss, all things being equal (calories, daily activity level) is it likely to for most people (on average) lead to more fat loss (or less fat storage) compared to not being in Ketosis?

Also, I have a kind of OCD for truly understanding things I know I only have a basic understanding of and metabolism has long been an area I am fascinated by (loved biology in school). Are there any 1,000 page text books you could refer me to which would give me a deeper understanding (sadly I am not kidding)?

JJ, I think, all things equal that some % of the population when given the choice between a Standard American Diet (SAD) and KD will have less adiposity on a switch. Whether it’s 30% or 70%, I don’t know, but Mark Friedman has suggested that the result of dietary switch from a combo high fat/high CHO (i.e., SAD) diet to something like KD can predicted by pre-existing fat oxidation potential.

Just noticed Teresa’s post. Please do not ever dumb it down (any more than you really have to) ever! I will have no where else to go for the real story!

I agree, don’t dumb it down. There are *plenty* of low carb websites that do that.

I’m a pre-diabetic low carber. Why is it that my body wants to regulate my fasting blood sugar between 100 and 110? Why not lower, like normal people? What can I do to make my body’s *desired* fasting BG lower?

@Tim

Some low-carbers get their fasting BG level higher than normal due to a “physiological insulin resistance”. To get it back to normal, you can do the following:

Add resistant starch in your diet.

Resistant starches are not digested in the small intetsine and do not contribute to your BG level at all. They go further down the colon and are fermented by beneficial bacteria. The overall effect of RS on metabolism is quite dramatic: lower fasting BG level, better regulation of BG and insulin spike after a carby meal (so-called “second meal effect”), better sleep, healthy colon (thanks to the short chain fatty acids like butyrate that these bacteria are spitting out).

You can find RS in something as cheap as raw unmodified potato starch (the fine white powder, Bob’s Red Mill is selling some, it is about 80% RS by weight which you can have as supplement – about 30-40g mixed in water or a smoothie), green bananas and plantains, etc. There’s this guy hosting a blog called freetheanimal.com He described RS and its effects at lengths in some of his articles. It is a fascinating topic and something a lot of type 2 diabetics or pre-diabetics could benefit from.

Thanks for a very (as usual) interesting post.

Yes the body is for sure complex. I would love, if you by any chance got the time, to dig in the subject of other hormones as well.

Being a well trained woman of soon 48 years with normal weight (53 kilo, 162 cm tall) i about a year ago started to have those famous “premenopausal issues”; nightsweats and difficulties sleaping. My gynecoligist gave me a description of vaginals containing estrogen. I have never in my life taken som kind of hormones, never been on the birth-controll-pills and other hormones. Suddenly I started gaining som weights, having cravings and felt very weird. Since eating a paleo diet I wasn’t used to have cravings. I thought to myself that I didn’t like how this had turned out so I got out on the internet and started my search. I found out that many women in my age doesn’t have low estrogen but are low on progesterone. Because of that, the body ca’t “use” the estrogen that is in the body. And then given som supplements with extra estrogen makes the body much more hormonally imbalanced.

I then bought som extra 5-hpt, L-tyrosene and started to use an progesterone cream during my luthealfase (and also quit using the estrogen medication from my gynecologist). Quite soon I feelt extremely well, started to loose those 2 kg I went up, started to taken the orderered estrogen from my gynecologist. I nowadays have no nightsweats what so ever and sleep like a baby

What I in many words above are trying to say, is that many women may have trouble with overweight because of hormonal inbalance. It may not be all of the solution, but since I experienced this myself (also as welltrained, eating healthy, not smoking and so on…) I think it would be important to hilight this.

I am also sad that many doctors (sorry Peter!) doesn’t seem to have a clue on this matter, giving many women estrogen and pills against depression, disturbing the bodys natural balance much more. I haven’t come across articles that show any correlation between insuline and hormones such as estrogen, progesteron and testosterone. But I think that they play quite an important roll. Also the hormones of the thyroid glands play such an important roll.

Love your work

(and ps. sorry for my poor english since being a sweedish lady 🙂 )

Susanne L

Susanne, I do look forward to addressing these issues down the line.

Peter, thank you for all you are doing in seeking real understanding of nutrition and how it affects the human body. One size (diet) so evidently does not fit all! And, has been pretty obvious to so many of us who have been casualties of what up until several weeks ago I would have called a healthy diet – vegetarian and no refined carbs, low fat. But no! For years I have suffered from dramatic energy swings – going from feeling extremely well for 24 hrs and then crashing if I’ve been at all energetic, as I like to be when well (I love to use my body previously being a dancer)and feeling so ill some days that I cannot move physically as I feel as if I have flu/can’t think straight/ low body temp aka Chronic Fatigue type symptoms. This cycle going on and on. A complete nightmare to plan my life and disguise it as it is so boring having to tell people – actually, I’m not functioning today…However, because I have had trauma in my life from a difficult childhood these highs and lows of energy have always been attributed to a mood disorder – from the biochemical positioned psychiatrists I am bi-polar and was recommended to take lithium. I refused. From the psychologists perspective I have Borderline Personality Disorder…Well, maybe both are right…and I very much believe in psycho-dynamic psychotherapy utilising attachment based theory. I have seen this work in my own training as working with abused children; and in my own case with a marvellously empathetic therapist. But it is not enough. There is more to this equation…I have always felt that foods affect me and my mood and sure diet is so much a bigger component, and thanks to the internet and my facility when my brain is functioning to actually think straight, really quite smart and able to grapple with the science when it is presented in a clear and concise way, as you seem to be able to. So, don’t ever dumb down your blog! Other passionate doctors too, are doing the same out there. So wonderful to have you share your knowledge, which is obviously extensive, but also acknowledge that what you know is still not enough; more questions (the right questions) need to be asked and to include everyone in this discussion is so refreshing, and empowering. Hopefully, it will mean people will come to see that their health is so often in their own hands and not to be just some passive bystander in a body that a doctor is meant to prescribe a pill to fix…Sorry, I digress! Anyway, I have been rigourously following a ketogenic diet following Drs Jeff Volek and Stephen Phinney’s advice on Low Carb eating and despite feeling truly awful 48 hrs after starting for about a week and a half, which having read how the body adapts can be expected, to in the third week now and although no real stamina yet, my mind is clear and my mood ‘just right’. No extreme high or low in mood. It is unbelievable to feel ok all day – no dips in energy really. Provided I don’t need to run anywhere. That kind of energy is eluding me right now. But, baby steps, eh? This is obviously too early to see if this can be really helpful long term to managing my moods and energy…but the very sparse amount of literature I am reading is pointing this way. Very few studies have been done with diet and bi-polar disorder and I think time it was really looked at. Keep up the work you are doing Peter. The NuSI seems such an exciting venture. I apologise I wrote so much and ‘off topic’ specific to the post.

Thanks for your comments and feedback, Rosie.

……………..

…………..

……………

Bestest Article Ever

This is like Christmas in July – you really out-did yourself on this one –

I always wondered why – exactly – I had to reduce my fat intake to lose weight – even in Ketosis

Jeff, so glad this was able to put that in context.

I’m so glad Jeff asked the question….the same thing was running through my brain.

Also thanks Peter- it’s finally hit me like a truck that it is not a “bad” thing that I’m not in Ketosis. For awhile, I thought it was the universal answer and to be “good” and losing weight, I had to be in it. Now I know this is not true, although, from the athletic point of view, the idea of metabolic flexibility just sounds so fantastic.

As for the comment to your friend Peter, Jeff’s question really supports your point #1 and #2. Not only are the posts so mind opening but the comments too!

Great write up, Peter!

The whole notion of “energy balance” and our modern obsession with calories can be depressing, so this post is certainly refreshing.

I look forward to the work you and others are doing which will help us focus on food choices and hormones and the role they play as the primary drivers of our metabolic health.

Thank you, Nathan. It will be a long journey, but it takes time to do things well, as I’m sure you (and all readers) can appreciate.

Thank you for the very interesting post!

I really like the point about the blood levels of B-OHB being unable to tell you definitelively about production or use. I made a similar point about blood sugar measurements being unable to tell you about the rate of GNG (https://www.ketotic.org/2013/01/protein-gluconeogenesis-and-blood-sugar.html), but I never thought about it in this context.

I’m also intrigued by your enigmatic description of the liver as master appetite regulator. There is a large faction of scientists who think it will turn out to be the brain. It will be exciting to find experiments that help distinguish these hypotheses.

As always, thank you for being honest about the limits of our knowledge. I have grown weary of people using authority and a good story to overstate their ideas. Even when I think a theory is likely to be correct, it bothers me to see it presented as such prematurely. You are a role model for the responsible scientist.

Amber

Thanks very much, Amber. I will definitely write about this topic of the role of the liver in appetite control.

Curious as to how fat cells collaborate in terms of which one of them will be releasing fat at any given point, and which once will be storing them if they are not needed in the circulation after an exercise for example. Can fat cells exchange fats between each other or there is some kind of line up or a queue that dictates which cells will be active in storing or releasing a particular lipid molecule. I think when people do crunches they might think that stomach fat is feeding that effort, while in reality it can be the fats in the neck. Just curious about how that decision is made by the body. I presume there is no simple answer.

Thank You,

Max

There is a entire cascade of cytokines that allow cells to communicate with each other but, frankly, much is still unknown.

Thanks for the very educational post, and blog. I have a theory about #2. First some background. After losing 25 lbs on a fairly strict low carb diet (not any particular one), I got careless a couple of times and went overboard on carbs. Each time, my next workout was a disaster. Part way through my normal running distance (3-4 km) I hit a wall – got weak, short of breath, had to quit early and hardly had the energy to do my stretches. That’s when I discovered the term “carb crash”. I believe I went out of ketosis back to purely carb-burning mode. Then, when my blood sugar went too low, I crashed, because I was out of fat-burning mode.

My theory is that ketosis gives a more consistent energy level throughout the day, at least if there’s a good supply of body fat to burn (which I still have). This keeps the energy level up between meals, resulting in more calories burned through the day. I’ve noticed I don’t hit the late afternoon drowsiness as much as I used to. It also gives me more endurance during exercise, allowing me to burn a lot more calories.

Thanks Peter – you give a lot to us, I hope you know how much it is appreciated.

I got the reference to ‘flux capacitor’. Dang, I loved that movie! I could never understand the bad reviews, I was hoping for a sequel. Time to watch it again. Oh well.

Fair Winds,

Cap’n Jan

Nevermind, of course they did. I just didn’t care for it. ;->

Thanks for the article Peter, been following you for over a year now, (you’re still one of the main inspirations for my 18 month old keto diet/lifestyle switch), and I’m still amazed by the quality of your research data. But am I the only one who thinks you have now made the Ketogenic Diet an altogether more complicated affair?

At the outset we were told, eat less carbs and a min of 60% fat and you’ll lose weight, then we were told…ahh but you can’t over do proteins. And now you’re saying, watch out, but you may have to restrict fats too.

How are we mere mortals expected to navigate such an increasingly complex set of rules without resorting to hair tearing and much gnashing of teeth?

Nigel, one who aspires to enter ketosis does not need to know anything in this post, to be sure. However, if someone is in ketosis, and is not losing fat, this post may offer some helpful insights.

Peter-

Thanks for another excellent post. Fantastic detail. One question (and I apologize if I missed this in your blog), what organelle is responsible for the conversion of fats to ketones in the liver cells? Lysosomes? Ribosomes? Mitochondria? Thanks in advance.

-Rob

Mitochondria.

Hi Dr. A-I was fascinated by your TEDtalk for nutritional interest and for social issues addressed (I’m looking to become a healthcare professional). What are your thoughts on the demonstrated (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11167929?dopt=AbstractPlus) decrease of thyroid hormone production / sensitivity as a result of absence of glucose in the diet and blood? I am also curious if you’ve read other concerns (not related to SFA intake / serum cholesterol) about very low carb lifestyle and alternative understandings of weight regulation that center around food-reward and hypothalamic inflammation. I’d also be grateful to hear your thoughts at some point on organ meats, bone broths, and fermented foods.

Cheers,

Michael

I think it’s another example of how hormones play an integral role in fat balance.

Hi Peter,

How is it that foods like dairy, and even protein like whey, which are very insulinogenic don’t seem to promote weight gain in studies, but carbs do? Is it simply a result of overeating the carbs?

Regards

Mark

I suspect so.

“Do they lose weight because they eat less? Or, do they eat less because they are losing weight?”

I suppose this is a way to grab people’s attention for a point you are trying to make. But boiling the issue down to this either/or proposition seems simplistic. Why can’t it be both? People overeat and undereat for a variety of reasons; appetite is a powerful driver, but not the only one.

The questions is posed directly in response to the observation I referred to. What is their appetite less in this setting? Is it because they are “eating themselves?” I argue, yes.