I know many of you are awaiting Part II of the mini-series on ketosis, but I’d like to digress briefly to comment on a study published last week, which a number of you have asked about.

In this study, by Hooper et al., titled Effect of reducing total fat intake on bodyweight: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies, the authors take aim at addressing one of the most important questions underpinning our current epidemic of obesity and, by extension, its related diseases: Is there a preferred dietary intervention that can lead to a long term reduction in body fat?

To address this important question the authors conducted an exhaustive meta-analysis of 33 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 10 cohort studies in which patients were treated with a low-fat diet for outcomes beyond weight reduction. For example, they examined studies which treated women at risk for breast cancer (e.g., due to abnormal mammography) with a low-fat diet to test if the diet reduced their likelihood of progressing to breast cancer. Or studies where subjects at risk for heart disease (e.g., due to biomarkers or a strong family history) were randomized to a low-fat diet versus a standard diet to examine the impact on biomarkers for heart disease.

Before getting into the details of this analysis I’d like to reiterate a point I made in a previous post. James Yang, one of my mentors when I was in medical school and again in fellowship, always reiterated, “a hundred sow’s ears makes not a pearl necklace” when talking about meta-analyses. Stated another way, Dr. Samuel Shapiro, a distinguished professor in Cape Town, South Africa, made this comment on meta-analyses:

“As a matter of logic, it is fallacious to argue that a series of inadequate studies taken together cancel out their inadequacies.”

In other words, a meta-analysis, no matter how large, no matter how elaborate in statistical tools, no matter how erudite in authorship, can be no better than the sum of its parts. To quote a good friend of mine, James Lambright, the former Chief Investment Officer of the TARP program, a meta-analysis “is somewhat analogous to ratings agencies looking at a huge pile of mortgages and concluding that collectively they deserve an ‘A’ rating, without noticing that the underlying mortgages might all be lousy.” Nice. A meta-analysis is basically a CDO. Some good…many not.

A close analysis of the 33 randomized controlled studies included in this systematic review reveals a common trend in most, though not all, of them. (I’ve not looked at the 10 cohort studies for the obvious reason – we will never glean cause and effect from such studies.)

The studies, almost without exception, followed a pretty typical pattern. The subjects were divided into two (sometimes more) groups and randomized into a treatment arm (or arms) and a control arm. Here is a typical example of how the investigators interact with the subjects in the treatment and control arms:

Treatment arm: Patients received individualized and/or group counseling to reduce fat intake and increase consumption of fruits and vegetables on a weekly and then monthly basis, often with cooking classes, behavioral interventions, and newsletters. In some trials, the counseling intervention for the low-fat diet arm included weekly or monthly calls from a study dietitian to troubleshoot dietary challenges.

Control arm: Patients received no, or very little, dietary counseling or interventions. Controls were simply instructed to consume their standard diet for the duration of the study.

To my counting, about 99.2% of the nearly 74,000 subjects (all but about 600 subjects) across the 33 RCTs examined were subjected to this treatment bias, referred to more specifically as performance bias. (Yes, this required actually reading — very quickly — each of the studies used in this analysis.)

According to the Cochrane methodology, the gold standard for research methodology, “performance bias refers to systematic differences between groups in the care that is provided, or in exposure to factors other than the interventions of interest. Randomisation of subjects and even blinding the investigators does not eliminate this (performance) bias.”

(I include this last comment about blinding because the BMJ study authors list the absence of blinding as a potential weakness of their study, though they don’t mention performance bias.)

In other words, it is not clear if the pooled effects observed in this meta-analysis reflect the low-fat dietary intervention, the counseling effect, or some combination of both.

Let me illustrate with an example. Assume you’re one of the subjects in the treatment group. Upon enrollment in the study, you undergo a lengthy assessment with a study dietician, where you provide a 5-day log of everything you’ve been eating for evaluation. You are given hours of counseling on how to avoid dietary fat. You are provided with menus and recipes to cook low-fat (and presumably healthy) dishes. Every few weeks you meet alone (or in group with other subjects in the low-fat arm) to receive additional support and counseling. Every month a study dietitian calls you to answer any questions you might have and to provide encouragement.

Does anyone think this intervention, regardless of what you’re being prescribed to eat, does not make a difference? If the guidance of the Cochrane group isn’t enough, I can absolutely attest to this from my experience working with people. We all benefit from encouragement, and the encouragement we get has an effect beyond the dietary composition.

This suggests a slightly different conclusion than that proposed by Hooper et al. Rather than concluding that lower total fat intake leads to small but statistically significant and clinically meaningful, sustained reductions in body weight in adults, it seems a more accurate conclusion would be that lower total fat intake, coupled to an intensive counseling and support regimen, leads to small but statistically significant and clinically meaningful, sustained reductions in body weight in adults compared to a standard diet without counseling and support.

Because the counseling effect could have other unintended effects, (for example, consumption of less sugar, fewer highly refined or processed foods, or more exercise), we can’t be sure what caused the measured effect.

The best studies in this space normalize for intervention effect across all treatment arms. This way the investigators have some way of assessing the impact of the actual intervention in question – the diet.

A couple of other oddities about this study

If you really wanted to understand the impact of a low-fat diet on weight loss (or some better marker of actual fat loss), it seems that actually looking at trials where this was being tested might be a better place to look. There is no shortage of such trials out there, including the work of Gardner, Foster, Ludwig, Dashti, Shai, and others. The advantage of looking at diet studies include:

- They usually remove the performance bias I described above. Typically (though not always) in these studies all subjects are given the same support and dietary counseling.

- Such studies are statistically powered to detect meaningful differences in the outcome or endpoint of interest – fat loss (or some proxy of it).

I’ve written before about the difference between statistical significance and statistical power, so I won’t repeat the explanation. But, I’d like to point out the problem of looking at endpoints that were not powered. The largest study included in this BMJ meta-analysis was the Women’s Heath Initiative (WHI), a study of nearly 50,000 post-menopausal women. The WHI, which I talked about at length in the presentation in this post, tested a low-fat dietary intervention over an average follow-up of nearly 6 years. The study was powered to detect hard outcomes like cancer incidence, heart attacks, and death. That’s why the study was so large. But when a study is this large, it’s actually quite easy to find statistical significance in any number of parameters, even if they are not clinically significant or relevant. Look at Table 3 from the JAMA report of the WHI:

You’ll notice that in waist circumference, for example, some of the subsets showed a statistically significant difference. Overall (bottom right section of table) the control (normal fat) group increased their waist circumference over the study from 89 cm to 90.4 cm, while the low-fat intervention group increased from 89 to 90.1 cm, a difference of 3 mm, which achieved a p-value of 0.04. While this is statistically significant (and therefore included in the BMJ paper as a study for consideration), it’s not really clinically significant. In fact, it’s not clear if any of the statistical differences in the WHI are clinically significant. Waist-to-hip measurements didn’t change, which of all the anthropometric changes is probably the most relevant to consider (absent actual body composition data).

Interesting side-note: both the treatment and intervention group lost a bit of weight, yet both groups saw an increase in BMI, suggesting they got shorter over the duration of the study. Furthermore, despite scrutinizing this table and the paper for longer than I care to admit, I cannot for the life of me explain the arithmetic. The authors logically define “change” as the difference between follow-up and baseline. However, examination of this table reveals the arithmetic to be incorrect more often than it is correct. Some instances may be attributable to rounding errors and significant figures, but many are not. It is possible drop-out accounts for this, I suppose.

My micro point

Notwithstanding the fact that the WHI suffered from performance bias:

“Women assigned to the control group received a copy of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans as well as other diet- and health-related educational materials, but otherwise had no contact with study dietitians. In contrast, women randomized to dietary intervention were assigned to groups of 8 to 15 participants for a series of sessions structured to promote dietary and behavioral changes that would result in reducing total dietary fat to 20% and increasing intake of vegetables and fruit to 5 or more servings and grains (whole grains encouraged) to 6 or more servings daily.”

The differences observed, despite this bias, were statistically significant because of the sample size, but were not clinically significant.

My macro point

A meta-analysis based on studies like this is not the best way to answer the question at hand. Sadly, I suspect, most providers (e.g., physicians, dietitians, nutritionists) may not appreciate this given how the media reports on this kind of publication.

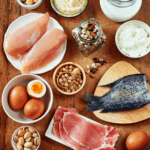

Photo by Beatriz Pérez Moya on Unsplash

For many years I frequented a weight loss centre. The goal was ketosis and I always lost weight.

I would receive injections of vit B6 and B12. It seemed to help with energy.

Now I am following the diet at home, it is a very, low calorie diet. Low in calories, fat and carbs.

Do you have any thoughts onthe injectable vitamins and their role in ketosis?

Thank you

Joy

Not sure how much of a role the injections play, if any. May be true, true, and unrelated, as the saying goes.

I’m learning much from reading some of your articles here on your site, and I am recently starting to look into ketosis for weight loss dieting. Any using ketosis, are you also adding a regime of exercise to go with it? I ask because some of the people I have spoken with using centers only focus on the nutrition side without working on building lean muscle mass. Thanks for any responses. I’m going to read some of your earlier thoughts as I appreciated this article. Thanks.

Hi Peter,

Just wanted to say i really enjoy your blog. I have been in nutritional Ketosis for about 8 week, prior to that i was following low carb paleo. However making the common mistakes of too much protein and too little fat. i am testing my blood ketones daily and must say i have great energy and no hunger. I actually have to remind myself to eat.

I am still finding my performance when exercising is not as good as it use to be, however i figure this will just take time. i have started taking bone broth, which has been great from my low blood pressure and light headedness.

Keep up the great work. Would be great if you came to Australia for a presentation!

Thank you, Sarah. I haven’t been to Australia since 2009, but it sure was amazing. I actually got to see Pearl Jam in concert twice in one trip! Once in Sydney and once in Perth. The best part, despite being there for over 2 weeks, and doing business in 6 cities, I got to swim in a 50 meter pool every single day I was there…You know they’re doing something right in a country when that’s the case.

Sadly, this was reported in the NZ papers as “low fat diets effective for weight loss” and I’m sure was seen by many as a counterblast to recent Taubesist-Lustigist propaganda successes in these parts.

“As a matter of logic, it is fallacious to argue that a series of inadequate studies taken together cancel out their inadequacies.”

Or in truck driver speak, “Garbage in, garbage out.” Another study for the nutritional study dump site, which, over the last 50 years, has been filling up rather rapidly. And, oh, the stench!

Thanks for doing the legwork. Now, if we could direct a few journalists your way.

Yes, that’s certainly a more direct way to say it.

I’m not sure if there is a more pressing need for better studies, or better interpretation of the existing ones!

The biggest lesson for me reading GC,BC was that I no longer blindly accept the word of “experts” no matter what authority they claim. I want to see evidence that will stand up to scrutiny.

BTW I am no completely clear if the mixed metaphor was intentional or not? I’ve heard of “casting pearls befroe swine” (a biblical reference) and “making a silk purse out of a sow’s ear” 🙂

It’s just what I used to call a “pure Yang-ism” … classic, and it sure made the point (at least to me!)

great points here- it should cause us to stop and wonder how much “sound” science is out there. But at that rate there are always so many variables at what point is is possible to truly test a theory? You can’t lock 2 big enough groups up and then only change one thing (like fat content) and keep them looked up long enough to see real data. Most of these studies only use people who still have to make their own choices and then self report, which could let to people cheating and not telling. Who could you get “real” data?

Peter,

Thank you for clarifying this and other studies, for all of us. I have enjoyed your blog posts and videos immensely. With your story as added motivation, I’m losing weight, getting in better shape, and feeling great!

In your videos and blogs, you’ve pointed out that protein creates less of an insulin response than carbs, but that it can depend on what else is eaten, what kind of protein it is, and how much it is. I’ve seen studies on Pubmed that seem to provide conflicting results (that protein alone, and protein with carbs, can cause a significant increases in blood glucose and the insulin response).

I suspect you could write a long answer to clarify this issue for us. That would be nice, of course, but I know you’re busy and have many priorities. Can you give us a summary version, about the insulin response from eating protein and the effect that may have on weight loss for those of us who are still insulin-resistant?

Thanks!

Richard

You’re right, Richard. The quality and preparation of the protein plays a huge role. For example, hydrolyzed whey protein probably kicks up more of an insulin fuss than, say, a bowl of rice. But the story is much more nuanced than just the insulin response. It’s more about what that insulin response drives (e.g., protein synthesis vs. impedance of lipolysis).

Dear Peter and other participants of this blog,

Desperately need your advice. I am a long distance runner, mostly marathons. I believe that I am very “carb tolerant” (49 yo,16.6% body fat, 5’6”, ~125 Lb, now running ~3:30 marathons, best 3:13), but my scientific nature pushed me to try low carb diet. The main goal is to see how switching to fat as a fuel will affect my sport performance. I am at week 5. Main problem: cannot tolerate running paces that were easy for me on carbs.

My ketones are dramatically dropping after workouts, and glucose is going up. Also, I have another observation that my resting heart rate is high: it was 45-48 on carbs, and now it is 55-58!

My theory is that I have fast increase in catecholamines to any stress inducers including running. This leads to fast release of glucose from liver (HGO), and then insulin is up and my fat oxydation is completely blocked. So, I cannot utilize fat and don’t have enough carbs to support my running. Also, catechoamines are known to incsease perceived exertion. I have the same response to other exercises, but I can tolerate better.

For example, yeasterday I did hot yoga (Bikram, 90 min, 105 F). Ketone before -1.3; after -0.2!

In general, my ketones are at the low end of ketosis, especially in the morning. I eat 85% fat, 30-40 g carbs, very moderate protein. Sodium intake is good. I do have a lot of positive effects: fast recovery post-workouts, not hungry, sustain level of energy, good mental concentration. I don’t want to give up, and I am not sure that I just need to wait longer and everything will be fine. Trying to be proactive. I need to start training for Boston marathon, but right now I cannot handle my training paces. Tomorrow I will have my annual medical exam. Any advices for lab tests? Thx a lot. Hope that together we will be able to solve this problem. I am sure that other people may experience the same.

I had similar issues when switching over to a ketogenic diet, especially on my longer road rides (30+ miles). Personally, I try not to eat any carbs going into the workout (I do carbs PWO), just electrolytes and a cup of coffee for a little caffeine. This seems to prime my body for metabolizing ketones the best, and during the ride I drink a mixture of water, electrolytes and Superstarch, which seems to keep my body mostly in ketosis while also adequately supplying glucose to my muscles. Since adding the Superstarch I have seen significant improvements, you should give it a try and see what you think. Good Luck!

Peter: I found Alla’s question quite interesting since I have experienced similar issues. I wonder if you can shed any light on what we are doing wrong or missing. Or does Ketosis not work for many of us?

Very difficult to address in a quick response. I have no idea what’s going on, but I would need a lot of data to sort out a few hypotheses. Hopefully subsequent post on ketosis may shed some light.

FWIW, I’ve had sort of the same response after 5 weeks. It has taken me more like 10 weeks to feel really good on a ketogenic diet. I can only say that I’m now feel the improvements in endurance and strength almost daily. I think you should keep it, make sure to get adequate protein – not too much not too little. Give it some more weeks and I think you’ll be able to perform at the same level again.

Alla,

I’m wondering if you have read “The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Performance”? https://www.amazon.com/The-Art-Science-Carbohydrate-Performance/dp/0983490716/

I believe this book was written to specifically address your concerns…

Good luck!

A lot to swallow there…….I’d say at 5 weeks, it is too early to determine your maximum benefit of becoming a true fat burner. All other data does not really matter much. This is a big change for the body. Keep on doing what you are doing…get the super starch for 2+hr runs. Keep documenting.

These are smart people organizing this type of analysis. They too know what you know about the flaws, yet this rubbish get’s published, and promoted in the media “as low fat is a good thing for your health.” Why???

The media are lagging indicators, not leading. The conventional wisdom is “lowfat = good”, and until that conventional wisdom is upset by thought leaders, the media will keep spouting it.

As for the people doing these meta-analyses, it’s all about the funding. For whatever reason, low-fat studies are still getting more funding than high-fat studies.

Have you read “Mistakes Were Made (But not by me)” by Carol Tavris?

You ever heard of “confirmation bias”?

Peter,

I also see the difficulty of doing a tightly controlled study. Speaking as a non-scientist I’m curious how useful it would be to do a “meta-analysis” of many n=1 experiments as the one that you do and that Jimmy Moore and many others are currently doing. If there were a place (possibly online) to collect success stories/blogs in a summary version that are done by fairly meticulous people like yourself I suspect that the total evidence would be very significant, even though not true “science”.

I am thinking of the possibility of including evidence in as diverse areas as ketogenic diets for weight loss, cancer treatment, epilepsy treatment, heart disease etc.

Birgit

As you know, I’m a huge believer in “n of 1” stuff, but I’m not sure it’s a reliable way to do science.

Among the pitfalls here, there would clearly be a massive selection bias that would undermine any meta analysis. You’d only be sampling a certain type of person: a super-motivated person who adopted a low carb diet, who was HAPPY enough with it to stick with it, is motivated enough to get special tests and report them online, who probably is or was overweight (hence adoption of the diet), who very likely has reason to be concerned with heart disease and diabetes (hence discovering this world in the first place). In short you’d be sampling a bunch of fat, carb-sensitive, insulin resistant but motivated and compliant people who read blogs (like me!).

Ha,ha, great explanation Kevin, that makes sense, and of course you are right. So I guess all of us who are doing these self-experiments will have to just continue doing them and sharing the results so that more people will give it a try. 🙂

The first thing that jumped out at me was this sentence “For example, they examined studies which treated women at risk for breast cancer “.

I have to think that if you take one group of at-risk people and tell them that they can affect their outcome by changing their lifestyle, they are going to have better outcomes that the group that is told “good luck!”

Hmmm. I think I just regurgitated what you already said. Ahh well.

Exactly…

Peter,

One of the main reasons I read your blog is the valuable insight you drop on developing one’s critical thinking (the other reason is how you discuss things starting with first principles, just like how Feynman would think). This post is an excellent demonstration of that. Unfortunately, to enumerate on such matter leads to lengthiness of your post, which turns off many people, an issue I sadly see no way around.

On another note, I would like to share with you an article that perhaps brilliantly illustrate another common trap buried in many scientific papers:

https://www.americanscientist.org/issues/id.15964,y.2013,no.1,content.true,page.1,css.print/issue.aspx

Thanesh, this is a fantastic article. Thanks very much for sharing. Completely agree!

Peter,

Someone recently showed this article to me so I can now forward something intelligent back. I’m amazed at people sending me articles to explain how I’m dieting incorrectly. I started on a ketogenic diet back in April and have gone from a 42″ waist to a 34″ waist.

Your work has been a tremendous help and has provided much appreciated encouragement. As it is the season, do you have a list of preferred charities for donations in your honor?

Thank you.

Sadly, Jim, I’m pretty sure not one person who sent you this actually read the paper, let alone one of the papers that went into the meta-analysis.

Donate to NuSI. It is the single best thing you can do to promote real research by real scientists.

Very interesting hearing your take on this study. My ears perked up when I heard that this study included no studies that tried to study weight loss. It reminded me of that great streetlight joke, “Why are you searching for your wallet here, sir?”

It would have been more interesting and even out some of the performance bias if they had also included several of the many wonderful studies with do-nothing SAD as the control and a high-fat diet studied as a way to reduce all ills. (OK, this is sort of another sad joke.)

Now as for your photos, clearly the high-fat pig parts came before the fat-free pearls, a good move indeed!

And speaking of performance bias, what would you call that bias that all LC’ers have to face when they are constantly taunted by well-meaning friends and medical professionals. For the LC diet to be successful, there has to be a very high level of “activation energy” input to counteract all that talk of “dangerous fad diets” while the low-fat folks get their brownie points issued immediately. Does overt hostility to one’s diet choices supply some hormetic effect to weight loss?

Hmmm. Not sure that represents a formal “bias” in the technical sense, but you’re absolutely correct this is an issue.

According to the study “Meta-analysis of data from the trials suggested that diets lower in total fat were associated with lower relative body weight (by 1.6 kg, 95% confidence interval ?2.0 to ?1.2 kg, I2=75%, 57?735 participants).”

1.6kg lower weight is pathetic. You could lose that on a trip to the can.

If you can lose 1.6kg/3.5lb in a bathroom session, I think you’d need immediate medical attention.

Peter,

I also want to thank you for sharing your empirically based insight on calling out the research community on their bluffs (yes, more than one).

How are the medical experts (clinicians) expected to properly address the clinically significant cause-and-effect data concerning our obesity epidemic, when the ‘evidence’ is fraught with misdirection and disguise?

Let alone convince the laymen (the public) of the efficacy, reliability or ‘trustworthiness’ of those findings?

Can you blame the public for being utterly confused and skeptical?

*sigh*

So much time is wasted.

(I’m a budding professional trying to make sense of the ‘garbage’)

Sean, this is what keeps me up at night. This is why I do what I do. We can do better than this and the excuse that it’s too tough or too expensive to do and report on research appropriately is no longer acceptable.

First, just wanna say thanks for the great work you do Dr. Attia. Answering so many comments like you do is going so far above and beyond, very kind of you. I finished taking notes (literally) on your ketosis part 1 article and will now begin the cholesterol articles as I await part 2. So, I have three questions, if you don’t mind.

What’s your take on this Chris Kresser article? Don’t feel you need to read it if you haven’t already. I can’t figure out what my strategy should be on that. https://chriskresser.com/when-it-comes-to-fish-oil-more-is-not-better

Which leads into my next question. It would be nice to have the ability to sort out the science myself. I’m taking notes on a 15ish page article called statistics for clinicians which is good so far. I also plan to read Bad Science. Do you have any other suggestions? Books, articles, textbooks?

Any input to the ‘euphoria’ phenomena? While in ketosis, if I carb up at night with high GI carbs (roughly 150 carbs), and then revert back to ketosis, I find I can attain euphoria over the next 3 days at times. That is, I feel very happy and not anxious. After 3 or 4 days the feeling goes away and I’m prone to anxiety again, though nothing like I feel on a high carb diet.

The middle question is the most important for me if you pick one!

Thanks. Keep up the good work.

Ben, glad you’re enjoying the content. I’ll try to address your questions.

1. This is an area that still has me completely stumped. I cannot make sense of this, but agree with Chris’ main point about the inability to properly study disease in the context of isolated nutrient supplementation. I’ve read most of the papers he cites here, and see his points, but some of them could also be interpreted another way. What to do? Well, I’m not sure. I do consume less than 3 gm/day of EPA and DHA (so not “high does”) and probably eat fish 1-2x per week. My RBC EPA and DHA levels are “normal,” for what that’s worth (I put “normal” in quotes because I don’t think we actually have a clue what normal is). I can absolutely speak to the dangers of too much EPA and DHA, so certainly over-doing it is an issue.

2. Francis Bacon

3. I’m not sure…

https://www.nature.com/ismej/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/ismej2012153a.html

Gut bacteria responsibke for obesity ? Couldnt find a way to email him seperatly and i have to get back to work.

Very likely that gut bacteria play a role in MetSyn (and, by extension, obesity). The question is how does what we eat impact them? Certainly other factors do, also, such as antibiotics play a role, but the real unexplored area is the role of food on gut biota.

Looks like the study is included … did you read it and whats your opinion of it ?

I look at it immediately said well they fed the guy non-digestible carbs .. which equals low carbs … which is what you called a variable right?

So id like you to dig onto this a little as i cannot make heads nor tail of what exactly they are saying.

Hi,

What tools I need to measure ketosis and where I can get them? Thank you.

Alex, info on how to measure Ketosis is in other parts of this blog.

https://eatingacademy.com/books-and-tools

See near the bottom.