I know many of you are awaiting Part II of the mini-series on ketosis, but I’d like to digress briefly to comment on a study published last week, which a number of you have asked about.

In this study, by Hooper et al., titled Effect of reducing total fat intake on bodyweight: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies, the authors take aim at addressing one of the most important questions underpinning our current epidemic of obesity and, by extension, its related diseases: Is there a preferred dietary intervention that can lead to a long term reduction in body fat?

To address this important question the authors conducted an exhaustive meta-analysis of 33 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 10 cohort studies in which patients were treated with a low-fat diet for outcomes beyond weight reduction. For example, they examined studies which treated women at risk for breast cancer (e.g., due to abnormal mammography) with a low-fat diet to test if the diet reduced their likelihood of progressing to breast cancer. Or studies where subjects at risk for heart disease (e.g., due to biomarkers or a strong family history) were randomized to a low-fat diet versus a standard diet to examine the impact on biomarkers for heart disease.

Before getting into the details of this analysis I’d like to reiterate a point I made in a previous post. James Yang, one of my mentors when I was in medical school and again in fellowship, always reiterated, “a hundred sow’s ears makes not a pearl necklace” when talking about meta-analyses. Stated another way, Dr. Samuel Shapiro, a distinguished professor in Cape Town, South Africa, made this comment on meta-analyses:

“As a matter of logic, it is fallacious to argue that a series of inadequate studies taken together cancel out their inadequacies.”

In other words, a meta-analysis, no matter how large, no matter how elaborate in statistical tools, no matter how erudite in authorship, can be no better than the sum of its parts. To quote a good friend of mine, James Lambright, the former Chief Investment Officer of the TARP program, a meta-analysis “is somewhat analogous to ratings agencies looking at a huge pile of mortgages and concluding that collectively they deserve an ‘A’ rating, without noticing that the underlying mortgages might all be lousy.” Nice. A meta-analysis is basically a CDO. Some good…many not.

A close analysis of the 33 randomized controlled studies included in this systematic review reveals a common trend in most, though not all, of them. (I’ve not looked at the 10 cohort studies for the obvious reason – we will never glean cause and effect from such studies.)

The studies, almost without exception, followed a pretty typical pattern. The subjects were divided into two (sometimes more) groups and randomized into a treatment arm (or arms) and a control arm. Here is a typical example of how the investigators interact with the subjects in the treatment and control arms:

Treatment arm: Patients received individualized and/or group counseling to reduce fat intake and increase consumption of fruits and vegetables on a weekly and then monthly basis, often with cooking classes, behavioral interventions, and newsletters. In some trials, the counseling intervention for the low-fat diet arm included weekly or monthly calls from a study dietitian to troubleshoot dietary challenges.

Control arm: Patients received no, or very little, dietary counseling or interventions. Controls were simply instructed to consume their standard diet for the duration of the study.

To my counting, about 99.2% of the nearly 74,000 subjects (all but about 600 subjects) across the 33 RCTs examined were subjected to this treatment bias, referred to more specifically as performance bias. (Yes, this required actually reading — very quickly — each of the studies used in this analysis.)

According to the Cochrane methodology, the gold standard for research methodology, “performance bias refers to systematic differences between groups in the care that is provided, or in exposure to factors other than the interventions of interest. Randomisation of subjects and even blinding the investigators does not eliminate this (performance) bias.”

(I include this last comment about blinding because the BMJ study authors list the absence of blinding as a potential weakness of their study, though they don’t mention performance bias.)

In other words, it is not clear if the pooled effects observed in this meta-analysis reflect the low-fat dietary intervention, the counseling effect, or some combination of both.

Let me illustrate with an example. Assume you’re one of the subjects in the treatment group. Upon enrollment in the study, you undergo a lengthy assessment with a study dietician, where you provide a 5-day log of everything you’ve been eating for evaluation. You are given hours of counseling on how to avoid dietary fat. You are provided with menus and recipes to cook low-fat (and presumably healthy) dishes. Every few weeks you meet alone (or in group with other subjects in the low-fat arm) to receive additional support and counseling. Every month a study dietitian calls you to answer any questions you might have and to provide encouragement.

Does anyone think this intervention, regardless of what you’re being prescribed to eat, does not make a difference? If the guidance of the Cochrane group isn’t enough, I can absolutely attest to this from my experience working with people. We all benefit from encouragement, and the encouragement we get has an effect beyond the dietary composition.

This suggests a slightly different conclusion than that proposed by Hooper et al. Rather than concluding that lower total fat intake leads to small but statistically significant and clinically meaningful, sustained reductions in body weight in adults, it seems a more accurate conclusion would be that lower total fat intake, coupled to an intensive counseling and support regimen, leads to small but statistically significant and clinically meaningful, sustained reductions in body weight in adults compared to a standard diet without counseling and support.

Because the counseling effect could have other unintended effects, (for example, consumption of less sugar, fewer highly refined or processed foods, or more exercise), we can’t be sure what caused the measured effect.

The best studies in this space normalize for intervention effect across all treatment arms. This way the investigators have some way of assessing the impact of the actual intervention in question – the diet.

A couple of other oddities about this study

If you really wanted to understand the impact of a low-fat diet on weight loss (or some better marker of actual fat loss), it seems that actually looking at trials where this was being tested might be a better place to look. There is no shortage of such trials out there, including the work of Gardner, Foster, Ludwig, Dashti, Shai, and others. The advantage of looking at diet studies include:

- They usually remove the performance bias I described above. Typically (though not always) in these studies all subjects are given the same support and dietary counseling.

- Such studies are statistically powered to detect meaningful differences in the outcome or endpoint of interest – fat loss (or some proxy of it).

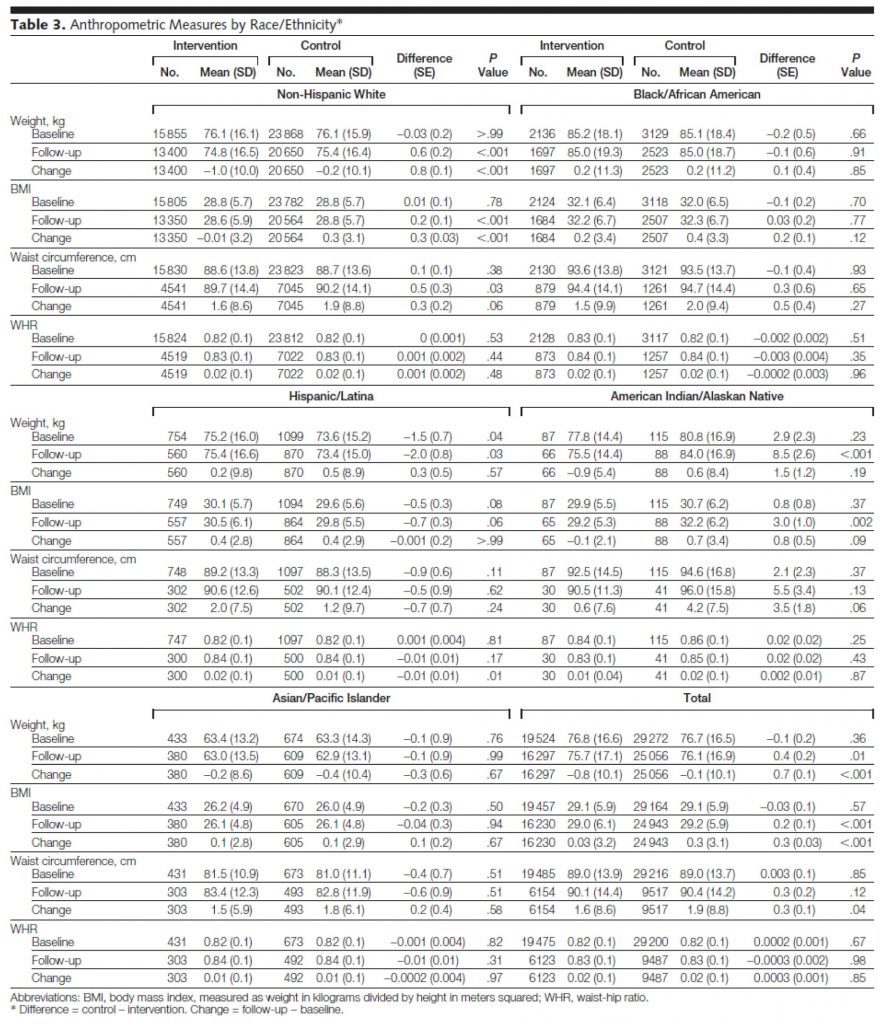

I’ve written before about the difference between statistical significance and statistical power, so I won’t repeat the explanation. But, I’d like to point out the problem of looking at endpoints that were not powered. The largest study included in this BMJ meta-analysis was the Women’s Heath Initiative (WHI), a study of nearly 50,000 post-menopausal women. The WHI, which I talked about at length in the presentation in this post, tested a low-fat dietary intervention over an average follow-up of nearly 6 years. The study was powered to detect hard outcomes like cancer incidence, heart attacks, and death. That’s why the study was so large. But when a study is this large, it’s actually quite easy to find statistical significance in any number of parameters, even if they are not clinically significant or relevant. Look at Table 3 from the JAMA report of the WHI:

You’ll notice that in waist circumference, for example, some of the subsets showed a statistically significant difference. Overall (bottom right section of table) the control (normal fat) group increased their waist circumference over the study from 89 cm to 90.4 cm, while the low-fat intervention group increased from 89 to 90.1 cm, a difference of 3 mm, which achieved a p-value of 0.04. While this is statistically significant (and therefore included in the BMJ paper as a study for consideration), it’s not really clinically significant. In fact, it’s not clear if any of the statistical differences in the WHI are clinically significant. Waist-to-hip measurements didn’t change, which of all the anthropometric changes is probably the most relevant to consider (absent actual body composition data).

Interesting side-note: both the treatment and intervention group lost a bit of weight, yet both groups saw an increase in BMI, suggesting they got shorter over the duration of the study. Furthermore, despite scrutinizing this table and the paper for longer than I care to admit, I cannot for the life of me explain the arithmetic. The authors logically define “change” as the difference between follow-up and baseline. However, examination of this table reveals the arithmetic to be incorrect more often than it is correct. Some instances may be attributable to rounding errors and significant figures, but many are not. It is possible drop-out accounts for this, I suppose.

My micro point

Notwithstanding the fact that the WHI suffered from performance bias:

“Women assigned to the control group received a copy of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans as well as other diet- and health-related educational materials, but otherwise had no contact with study dietitians. In contrast, women randomized to dietary intervention were assigned to groups of 8 to 15 participants for a series of sessions structured to promote dietary and behavioral changes that would result in reducing total dietary fat to 20% and increasing intake of vegetables and fruit to 5 or more servings and grains (whole grains encouraged) to 6 or more servings daily.”

The differences observed, despite this bias, were statistically significant because of the sample size, but were not clinically significant.

My macro point

A meta-analysis based on studies like this is not the best way to answer the question at hand. Sadly, I suspect, most providers (e.g., physicians, dietitians, nutritionists) may not appreciate this given how the media reports on this kind of publication.

Photo by Beatriz Pérez Moya on Unsplash

Peter: After reading your blog the past year, and others, when I see an article reporting on a study like this I can immediately pick it apart (without even reading your current post). . . so thank you. The study looks worthless to me, no more than if you cut out eating some crap and eat low fat, of course you will lose weight. What if you cut out crap and carbs and ate fat? If you took a segment of those 78,000 or so and put them on paleo style low carb diet, up to 100G carb per day or so, the results would be stunning, just as in our family this year, first we stopped consuming sugar (not crazy amounts, but more than one would think), and lost weight. But the dramatic results occurred after we cut out all the grains and beans and ramped up fat consumption. You would be looking at much more than a 3 pound difference! (Sadly to say with almost no exercise, that’s next year’s challenge).

A 3-4 pound difference looks pathetic to me. Is that really clinically significant?

Thanks for your blog, it is appreciated.

Peter, I went to the WHI study of over 48,000 women that you speak about.

Not noted in the description above of the results is the following from from that study,

From the Comments-

“Weight loss from baseline through the follow-up period was greatest among women who had the greatest decrease in percentage of energy from fat; the small number of women who increased percentage of energy from fat during the study showed weight increases.”

https://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=202138

Also not noted, is that while the WHI 7.5 year long study used the “goal” of having only 20% of calories as fat, the actual participants ended up at 29.8% of calories as fat. Hardly representative of the diets suggested by Dean Ornish and others in that crowd. I believe Ornish participants were closer to 10% of calories as fat.

Certainly not above 15%, or in effect only half of what the results of the WHI report at 29.8% for the intervention group.

While cleary there probably is a performance bias in the WHI study, it is interesting to note that even in the control group, the women who ate less fat also lost more weight relative to other women in the control group.

As they put it in the abstract —

“Weight loss was greatest among women in either group who decreased their percentage of energy from fat. ”

We can’t attribute that to performance bias for those in the control group.

Wade, the authors of the WHI, when it was published, were basically criticized for a few things:

1. The subjects were not compliant enough with the low fat, high grain, high F/V diet, seeing only a modest change from the control. Given the performance bias, this may suggest such an intervention is harder to follow than folks think, but also that their intervention methods were insufficient.

2. Only post-menopausal women were included. I think this was necessary to get a homogeneous enough population to ask the question they were asking…but it does imply the lessons learned (reducing fat slightly and increasing grains and F/V slightly had no impact on health) only apply to this population.

3. Some said the study was too short (median follow-up was 5.7 years, I believe) to “capture the benefit.” I think this is incorrect. If you can see a change in 5.7 years…I don’t think you’re seeing one.

Most nutrition test/study data that reaches the popular press is based on comparisons within the context of a glycemic diet, gluten-bearing grains and all. This is such a “high noise” environment, that it’s wonder any signal can be measured at all – entirely apart from flawed techniques. It’s particularly amusing when the outcome they are trying to measure is being largely caused by factors they are entirely ignoring.

I’d hazard that pretty much everything we think we know about food is going to have to be retested in a keto context. I’d be curious, for example, to see things like wine and coffee studied that way. Perhaps the cycle of see-saw headline conclusions would vanish, and there would be an unambiguous result.

Meanwhile, we get studies that might as well conclude: “This investigation was based on two well-known scientific principles: observer bias and placebo effect. Needless to say, we got the results our sponsors were hoping for.”

I’ve been N-1 on what happens when you go back to a moderate SAD after having been low-carb for a while and it isn’t pretty. In about 3-4 months I’ve put on 20+lbs. Some of that is muscle (been doing a powerlifting type program up until 2 weeks ago), but most is flab. The biggest change was I started drinking microbrews again, had occasional sweets, and didn’t strictly avoid bread, rice, etc. I’m 6’4″, now around 205; so it’s not crisis time..but this drives home how easy it is for some of us to plump up and how low-carb may need to be more of a lifetime lifestyle change than a sporadic visit to keep weight under control. I have work to do in that dept; I previously viewed it as an aesthetic choice, but now seeing how my body reacts to even moderate amount of CHO, I’m moving on to seeing it as necessary if I want to be healthy later in life and avoid MetSyn..hard pill to swallow when society tells you to look the other way and you seem otherwise healthy to most..meaning, no one looks at me and thinks I’m obese or have health issues.

FWIW- I’m a recovered endurance athlete who used to gulp carbs..and a recovered undiagnosed alcoholic who likely still has addiction issues with food/booze.

You wrote in material part: “I know many of you are awaiting Part II of the mini-series on ketosis . . . .”

Yes, we are.

Interesting since a reasonable study comparing low carb with regular diets was done at Stanford FIVE years ago and showed Low Carb worked better. (New England Journal of Medicine.) Was that part of the Meta-analysis? I doubt it.

In light of your comments, Peter, the obvious study would be to compare a low fat with a low carb group with comparable support: diet, cooking advice, encouragement, etc. You would have to have the counselors equally committed to their study arms, also; someone forced to counsel low carb who did not believe in it would unconsciously send all kinds of subtle disapproval messages. Another approach would be a crossover–force low fatters to counsel low carb and low carbers to counsel the low fat!

For a future post, consider analyzing the various kinds of bias that can afflict us all and put them all in one place with short examples. The loss of critical thinking skills makes dummies of us all, even those with too much education like me. (MD and PhD from Duke, 1983…)

Jim, the study you’re referring to, I think, is Christopher Gardner’s Stanford “A TO Z” trial. It was excluded, along with a dozen other good trials because it was a weight loss trial. This meta-analysis only included studies that *specifically* studied anything but weight loss.

So they did an analysis and concluded that low fat diets helped weight loss, but excluded weight loss trials. Makes sense to me…

My thoughts exactly.

Just a word about the Stanford A to Z study as comparing low carb vs low fat.

Here is how the participants of the two of the 4 diets followed the intended guidelines.

Those on the “low-carb” Atkins diet were suppose to aim for 20 – 50 grams of carbs per day.

They began with their normal intake at 215 grams per day.

At 8 weeks they were down to 60 grams per day. (not bad)

At 6 months they were at 115 grams per day

At 12 months they were at 140 grams per day

Now look at the “low-fat” Ornish comparison group

Their stated goal for comparison purposes was to have their fat as a percent of calories be at 10%.

They began with their normal diet at 35% fat

At 8 weeks, they were at 21% (more than double the study goal)

At 6 months they were at 28%

At 12 months they were at 31% (more than triple the study goal)

Thus, using the Stanford A to Z study as a “comparison” of low-carb vs low-fat of the Ornish style is very misleading, unless you are really looking at compliance versus non-compliance as the key investigation point.

The key advantage the Atkins group seemed to have had was the ease to stay closer to the study goals.

Had each group been at, say, 90% compliance, then we could make some statments about the actual diets effectiveness.

There are large groups of people out there doing 50 grams per day of carbs and 10% fat calories.

Who knows how a dedicated group of each would come out after 12 months.

Wade, if you look at the 6-month data (or it may have been 3-month), when all the subjects were still closer to their prescription diet, the results hold.

Furthermore, I’d make a distinction to your point. After the study was published Barry Sears (ZONE diet) was angry because the study suggested his diet wasn’t particularly useful. In fact, he looked at where the Atkins folks ended up (they basically were 40/30/30 at the end of the study) and said, “Look — they were on the ZONE diet by the end of the study and they did the best!” True, but not true. They only got there because they didn’t stay where they were guided. Same argument for Ornish. But don’t confused efficacy and effectiveness. You are talking about the latter, which is fair. But we can still learn about the former from this study, which is a very important take-away. The folks who ate more fat — regardless of diet nomenclature — did better (on average).

“But we can still learn about the former from this study, which is a very important take-away. The folks who ate more fat — regardless of diet nomenclature — did better (on average).”

True, at the end of 12 months, those on (to some degree) the Atkins diet had lost about 10 pounds.

Those on (to some degree) the Ornish diet lost about 5 pounds.

However looking at the graphs in that study, Fig. 2, and the weight gain trajectory of the final 6 months, it appears that within 1 year, all the advantage of the Atkins group would disappear.

I wish they had broken out and presented those few partipants who followed the original study goals.

The follow up version of this study (enrolling subjects beginning in April) will be much less ambiguous. It will be an epic study.

I am looking forward to seeing the results of the efficacy trial. I have so many questions! A few:

Is the research design for the trial beginning enrollment in April published? Online?

Where is it being done? Which team(s)? In the depths of the obesity epidemic, such as the Deep South of the US? Children? (This epidemic could have such powerful effects on future populations, through epigenetics as well as culture.)

Will interim results. — e.g. 3- , 6- month — be published? Revealed here or at NuSI.org?

Again, thank you so much, Peter.

Jane

All in time.

Hi Peter ,

Thanks for another great post.

Someone else has probably pointed this out, but I was looking for the NuSI website and accidentally ended up at NuSci instead. At first I thought you had redesigned the NuSI website, but when I started reading, I thought I was losing my mind — the movie Forks over Knives was highly recommended!?! The book the Starch Solution was recommended!?! It only took a minute or two to realize the mistake and I went to NuSI, but how much difference one little letter can make!!

Shouldn’t take too long to figure out that’s not NuSI…

Hi Dr. Attia, love the blog, I’ve learned a lot and enjoy reading your posts. I know given your personal experience you have said you believe exercise is not effective in weight loss (off thread topic I’m sorry). I assume you believe that exercise induces hunger, thus the more you exercise the more you’ll eat just to keep up with your exerted energy, (i.e. your body is trying to keep you in a state of equilibrium) and you won’t necessarily gain or lose weight (except gains from lean tissue). Do you still believe this? Do you believe this holds true whether you are insulin resistant or not?

I simply can’t wrap my head around exercise not being a useful tool in weight lose. Obviously I believe diet is the most effective way to make changes, (more so when considering how many people would routinely exercise compared to simply changing what they eat) but I don’t see how 30-45min of light-moderate aerobic exercise couldn’t be beneficial in addition to the dietary changes.

Let’s say someone exercises at 7PM and then eats their normal HFLC meal, (assuming they had no circulating insulin whilst exercising) is it then assumed they will eat a bigger meal because they exercised, thus replacing whatever may have been lost? Will they eat more later, because of the exercise? What if they simply exercise late enough so they sleep shortly afterward, and thus they are unaware of any hunger pains associated with the exercise? Will the fact that they ate their normal scheduled meal following the exercise, satiate them from their added hunger brought on by the exercise? Hypothetically speaking, what if they simply can ignore any hunger that might be brought on by the exercise? What if not everyone is so susceptible to increased hunger or drive to eat more from exercise?

I’m on the fence. If there is a weight control effect, it’s a fraction of that you see from dietary change. The data, when really parsed out to remove intervention effects, is not compelling. But here’s my question for you: Who cares? If you love to exercise, as I do, do it for the other reasons. If you’re only exercising for weight control, I worry you’re in tenuous relationship that may end in disappointment. If you exercise for the “right” reasons (in my opinion), you’ll be a lifer and get so much more joy out of it.

Hi Peter,

I wondered if you had any thoughts on the recent US News & World Report that came out ranking the best diets of 2012. No surprise (even if wrong) in that low-fat diets that recommended avoiding red meat made the top of the list. Meanwhile Atkins and Paleo-like diets were toward the very bottom.

Hope all is well. Really enjoy the blog!

Brian

Look at criteria for ranking…compliance with “formal guidelines” gets most points.

Hi Peter –

Thank you so much for the site. I hope you don’t mind, but I wanted to point something out that bothered me while reading the article. It seems like your goal was to discredit the study mentioned, and to raise a healthy amount of skepticism in your readers’ minds about the validity of the study’s claims. To do that you began by attacking the meta-analysis as a methodology.

The key takeaway in the first part of the article is that meta-analyses are of dubious value because of the principles of the endeavor, regardless of the quality of their construction. If your point was to invalidate the study based on its methodology, I think you could have done more to reinforce that point. Currently, you do not provide a data-based refutation of meta-analyses, which would have strengthened your attack.

Although I don’t mean to nit-pick, you have used meta-analysis in your JumpStartMD videos on the role of dietary fat in weight loss as a point supporting LC diets. It doesn’t follow that you would raise an attack on the meta-analysis as a methodology to detract from its validity when the conclusion of the paper is in opposition to your own views, but withhold that objection when the meta-analysis supports them.

The reason I am writing this critique of your article is because I would prefer that you not raise the issue of the invalidity of meta-analyses unless you are going to substantially support it. I object to it because many of your readers may not have the necessary experience to form their own views on the subject. Because of the excellence of the other posts on the site, and because of your general rigor and intellectual acuity, you may have a halo-effect of acceptance that extends to even weakly supported points. Since one of your related goals is to stop the spread of bad science and to arm your readers with better tools for detecting bad science, I felt this may slightly violate your own principles.

I still deeply appreciate the work you are doing on this site, and I hope my small critique does not offend you in any way, as that is not my intent.

Best,

Aaron

Thanks, Aaron. I’m not offended at all, and appreciate your comments. Though I may not have made the point clearly, this is my point: There is nothing wrong with a meta-analysis. But a meta-analysis is only as good as the sum of its parts. A meta-analysis of good studies has the potential to be good. A meta-analysis of flawed studies can not be good. In this specific cases, virtually every one of the studies suffered from a well-documented bias — a fundamental flaw that invalidates that conclusions of of the meta-analysis authors — called performance bias. It’s important to note that this does not mean the studies themselves were flawed! If the individual studies were looking to ascertain the impact of counselling + diet, then performance bias it not an issue! It’s only an issue for the meta-analysis, because of their hypothesis and what they sought to test.

So I stand very firmly by my assertion. This meta-analysis is fundamentally flawed, specifically because it claimed to examine the role of a low fat diet (vs. a low fat diet + extensive counseling).

Hi Peter,

How would you respond to this article?

https://www.tcolincampbell.org/courses-resources/article/lowcarbohydrate-diets-health-advisory-health-risks/?tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=76&cHash=2263a1b6e98428f898c1111fc7d14eb3

I am inspired by your health improvements and your desire to discover what foods lead to optimum nutrition. It is something I slso try yo do but do not have the scientific or medical background.

I am wondering what you see wrong with the article I linked to. Thanks!

Dan

My entire blog is the response to this. CF: observational epidemiology. Read the post I wrote last year on red meat.

In your blog entry on “How I lost weight” you present 3 pie charts showing how your diet evolved. This post should go there, but there is no ‘comments’ section on that one.

However my understanding of the “Typical American Diet” is that he is somewhere between chart 2 and chart 3 already, getting 40-50% of his calories from fat, and the rest as a roughly even split between protein and carbs.

There may be merit in showing how PA’s plan is different from the TAD. Showing the TAD pie chart with carbs split into sugar, high glycemic carbs, and low glycemic carbs may make the distinction more clear.

***

Another set of blogs I’d like to see: How do we measure progress if we aren’t in the position to get all these tests done. (AFAIK I don’t think that LDL-P is even available here.)

The other issue that comes up if we are looking for heart health, weight loss, and working endurence: How to do this without going broke?

***

There are several outfits, some diets, some just data companies, that you can record everything you eat on a daily basis. ( I know your attitude toward observational studies. My training was in astrophyics and geology. Our experiments are hard to budget for.) However: It would seem to me that taking participants who have made good records for a year, and enrolling them in a study, much like the framington study where you tried to nail down as many factors as possible, might yield some interesting things to check.

***

According to the best data available from NHANES, the average American consumes 15-16% of their calories from protein; 50-55% from carbs; the rest from fat. Formal guidelines call for more carbohydrate, less fat.

Dear Peter, thank you so much for the work that you have been doing in this area! I have great hope for NuSi and will continue to watch its progress. So this N of 1 is baffled about what’s been happening since I finetuned my eating habits to be consistent with the science you and Gary Taubes have so effectively presented. I started from having been on the South Beach Diet, so my labs were pretty good by then (the pedestrian ones, not the sophisticated ones you conduct), but I was always struggling against the pull of “the bad stuff.” Since committing further to (switching to , really, given what I’ve learned from you) a LCHF lifestyle, however, my labs have remained great, I feel great, with tons of energy, and I don’t struggle with “the bad stuff” at all, BUT my number weight has gone up significantly (20 lbs in 2 years) and, at least according to Ketostix, I’ve never been in ketosis (maybe that’s due to my drinking a glass of wine per night?). I am not asking for an analysis of what’s going on; I just want some ideas on what to “experiment with” to see what might be driving the weight gain (oh, I should also have said that I went from being very toned through weekly personal training sessions to almost no exercise at all due to a change in jobs). Any feedback would be appreciated.

Impossible to troubleshoot like this, but one glass of wine each night, under most circumstances, should not interfere with ketosis, if that is what you are striving for.

I know, so can you suggest a type of person to troubleshoot with? My current doctor is on the traiditional nutritional camp, and I’m not sure how to search/find someone withiin this nutrition belief system. Any websites/databases with lists of doctors or other types of professionals? Thank you in advance to anyone who can offer help.

Perhaps Jimmy Moore’s website for a physician, or look for a health coach who understands carb reduction?

Thank you, Peter, for this provocative and engaging website. I recently read both you and Gary Taubes and found myself extremely compelled by the evidence you have presented for ketogenic diets. I have adopted your approach and am currently down 22 pounds and I no longer experience violent swings in energy. Regarding fats: I have begun cooking with lard and was disappointed to see that commercial lard is almostnalways hydrogenated. A 13 g serving has about .5 g of trans fat. Is this within an acceptable range or should I dump the lard and opt for something else?

Not really sure. 0.5 gm is pretty small. You may wan to try coconut oil, butter, or ghee.

Hey Peter…love your blog. I have a question. I had a biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch 4 years ago. They removed about 80% of my stomach and rearranged my intestines to aid in weight loss. As a result, I only absorb approximately 60% of the protein that I eat (and only about 20% of the fat that I consume!). If I weigh 70 kg and 1.5 g per kg means I should consume about 105 g of protein, would you suggest that I shoot for about 175 g of protein to account for the malabsorption? I am trying to stick to 50 carbs or less per day, but my fat has been no where near the amounts that you have been consuming. It has been at about 135 g per day. Is it essential to up the fat grams to achieve nutritional ketosis? Add in heavy cream, butter, etc. so my overall numbers go up? Thank you for your time…I appreciate all that you do.

Peter, I understand your view that a low-fat diet is not necessary for weight loss. However, I’m having difficulty finding support on your blog for the proposition that a high-fat diet is more optimal? Once someone like myself takes the first four steps you’ve recommended in the “How can I lose weight?” section on your blog, what are the reasons for increasing fat intake? And why should someone limit intake of protein?

As a general comment, your blog has been eye-opening for me, and since first reading it only a week ago (after a friend shared your TED talk), buying Gary Taubes’s book, and adopting some of your recommendations, I have experienced noticeable improvements to my health. Many thanks for your contributions.

It’s really a function of what you’re optimizing for. I can’t really answer your question directly, Dan, without much more context. For what it’s worth, most (though not all) studies that pit fat-restricted diets versus carb-restricted diets find the latter to have superior results with respect to weight loss, BP control, and most biomarkers of disease risk. Some have found no difference, though I argue they found no difference because of poor study design which did not create sufficient dietary discrimination.

Hi Dr. Attia, thanks so much for your response (and recent post on fat flux). Can you explain what happens to dietary (and specifically saturated) fat consumed that is not used as energy? Is it absorbed into the body but not into the fat cells? Or possible excreted out? Perhaps I’m not articulating this question the best way, but basically I’m trying to figure out how the body processes saturated fat, and why for some people consuming more fat would be better than less.

To provide context, I am experimenting with ketosis with the goal of losing 6-8 pounds and eliminating my constant sugar cravings (and daily highs/lows from my former high carb diet). Now my question is “to fat or not to fat,” (e.g. South Beach or Atkins). Many thanks again for your important contribution in this field!

If not used as energy, it’s stored as fat (via RE process) or shed from the body in the GI system.

Hi there is another study I encountered in researching ketosis that links ketosis to cancer, called “Ketones and lactate increase cancer cell “stemness,” driving recurrence, metastasis and poor clinical outcome in breast cancer: achieving personalized medicine via Metabolo-Genomics.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21512313.

Does this mean a ketosis diet is not effective for breast cancer patients and those at risk for breast cancer?

Thanks

I don’t think so. This team ignores animal and human data showing KDs reduce tumor growth and extend life span. It is interesting (at a minimum) that there is no mention of Seyfried, Scheck, Eugene Fine or Dr. Peter Petersen’s studies in all Lisanti’s papers.

For reference, here is a talk by Petersen. https://videocast.nih.gov/summary.asp?live=7542

Listanti uses models and methods that are not relevant to human cancer, at least according to most experts I interact with.

The group appears motivated by greed and is mixed up in a lawsuit with stolen IP.

https://www.law360.com/articles/366951/university-says-cancer-research-team-defected-stole-ip

I was very impressed by your seminars and articles but am very confused by the contradicting ideas that you share and those from the plant-based group who are for starch and vegetable based diets with no fats and meats and seem to argue that they have a lot of science behind why that is the way to go and yours is not. Can you please make an article or a response video to that?