I know many of you are awaiting Part II of the mini-series on ketosis, but I’d like to digress briefly to comment on a study published last week, which a number of you have asked about.

In this study, by Hooper et al., titled Effect of reducing total fat intake on bodyweight: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies, the authors take aim at addressing one of the most important questions underpinning our current epidemic of obesity and, by extension, its related diseases: Is there a preferred dietary intervention that can lead to a long term reduction in body fat?

To address this important question the authors conducted an exhaustive meta-analysis of 33 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 10 cohort studies in which patients were treated with a low-fat diet for outcomes beyond weight reduction. For example, they examined studies which treated women at risk for breast cancer (e.g., due to abnormal mammography) with a low-fat diet to test if the diet reduced their likelihood of progressing to breast cancer. Or studies where subjects at risk for heart disease (e.g., due to biomarkers or a strong family history) were randomized to a low-fat diet versus a standard diet to examine the impact on biomarkers for heart disease.

Before getting into the details of this analysis I’d like to reiterate a point I made in a previous post. James Yang, one of my mentors when I was in medical school and again in fellowship, always reiterated, “a hundred sow’s ears makes not a pearl necklace” when talking about meta-analyses. Stated another way, Dr. Samuel Shapiro, a distinguished professor in Cape Town, South Africa, made this comment on meta-analyses:

“As a matter of logic, it is fallacious to argue that a series of inadequate studies taken together cancel out their inadequacies.”

In other words, a meta-analysis, no matter how large, no matter how elaborate in statistical tools, no matter how erudite in authorship, can be no better than the sum of its parts. To quote a good friend of mine, James Lambright, the former Chief Investment Officer of the TARP program, a meta-analysis “is somewhat analogous to ratings agencies looking at a huge pile of mortgages and concluding that collectively they deserve an ‘A’ rating, without noticing that the underlying mortgages might all be lousy.” Nice. A meta-analysis is basically a CDO. Some good…many not.

A close analysis of the 33 randomized controlled studies included in this systematic review reveals a common trend in most, though not all, of them. (I’ve not looked at the 10 cohort studies for the obvious reason – we will never glean cause and effect from such studies.)

The studies, almost without exception, followed a pretty typical pattern. The subjects were divided into two (sometimes more) groups and randomized into a treatment arm (or arms) and a control arm. Here is a typical example of how the investigators interact with the subjects in the treatment and control arms:

Treatment arm: Patients received individualized and/or group counseling to reduce fat intake and increase consumption of fruits and vegetables on a weekly and then monthly basis, often with cooking classes, behavioral interventions, and newsletters. In some trials, the counseling intervention for the low-fat diet arm included weekly or monthly calls from a study dietitian to troubleshoot dietary challenges.

Control arm: Patients received no, or very little, dietary counseling or interventions. Controls were simply instructed to consume their standard diet for the duration of the study.

To my counting, about 99.2% of the nearly 74,000 subjects (all but about 600 subjects) across the 33 RCTs examined were subjected to this treatment bias, referred to more specifically as performance bias. (Yes, this required actually reading — very quickly — each of the studies used in this analysis.)

According to the Cochrane methodology, the gold standard for research methodology, “performance bias refers to systematic differences between groups in the care that is provided, or in exposure to factors other than the interventions of interest. Randomisation of subjects and even blinding the investigators does not eliminate this (performance) bias.”

(I include this last comment about blinding because the BMJ study authors list the absence of blinding as a potential weakness of their study, though they don’t mention performance bias.)

In other words, it is not clear if the pooled effects observed in this meta-analysis reflect the low-fat dietary intervention, the counseling effect, or some combination of both.

Let me illustrate with an example. Assume you’re one of the subjects in the treatment group. Upon enrollment in the study, you undergo a lengthy assessment with a study dietician, where you provide a 5-day log of everything you’ve been eating for evaluation. You are given hours of counseling on how to avoid dietary fat. You are provided with menus and recipes to cook low-fat (and presumably healthy) dishes. Every few weeks you meet alone (or in group with other subjects in the low-fat arm) to receive additional support and counseling. Every month a study dietitian calls you to answer any questions you might have and to provide encouragement.

Does anyone think this intervention, regardless of what you’re being prescribed to eat, does not make a difference? If the guidance of the Cochrane group isn’t enough, I can absolutely attest to this from my experience working with people. We all benefit from encouragement, and the encouragement we get has an effect beyond the dietary composition.

This suggests a slightly different conclusion than that proposed by Hooper et al. Rather than concluding that lower total fat intake leads to small but statistically significant and clinically meaningful, sustained reductions in body weight in adults, it seems a more accurate conclusion would be that lower total fat intake, coupled to an intensive counseling and support regimen, leads to small but statistically significant and clinically meaningful, sustained reductions in body weight in adults compared to a standard diet without counseling and support.

Because the counseling effect could have other unintended effects, (for example, consumption of less sugar, fewer highly refined or processed foods, or more exercise), we can’t be sure what caused the measured effect.

The best studies in this space normalize for intervention effect across all treatment arms. This way the investigators have some way of assessing the impact of the actual intervention in question – the diet.

A couple of other oddities about this study

If you really wanted to understand the impact of a low-fat diet on weight loss (or some better marker of actual fat loss), it seems that actually looking at trials where this was being tested might be a better place to look. There is no shortage of such trials out there, including the work of Gardner, Foster, Ludwig, Dashti, Shai, and others. The advantage of looking at diet studies include:

- They usually remove the performance bias I described above. Typically (though not always) in these studies all subjects are given the same support and dietary counseling.

- Such studies are statistically powered to detect meaningful differences in the outcome or endpoint of interest – fat loss (or some proxy of it).

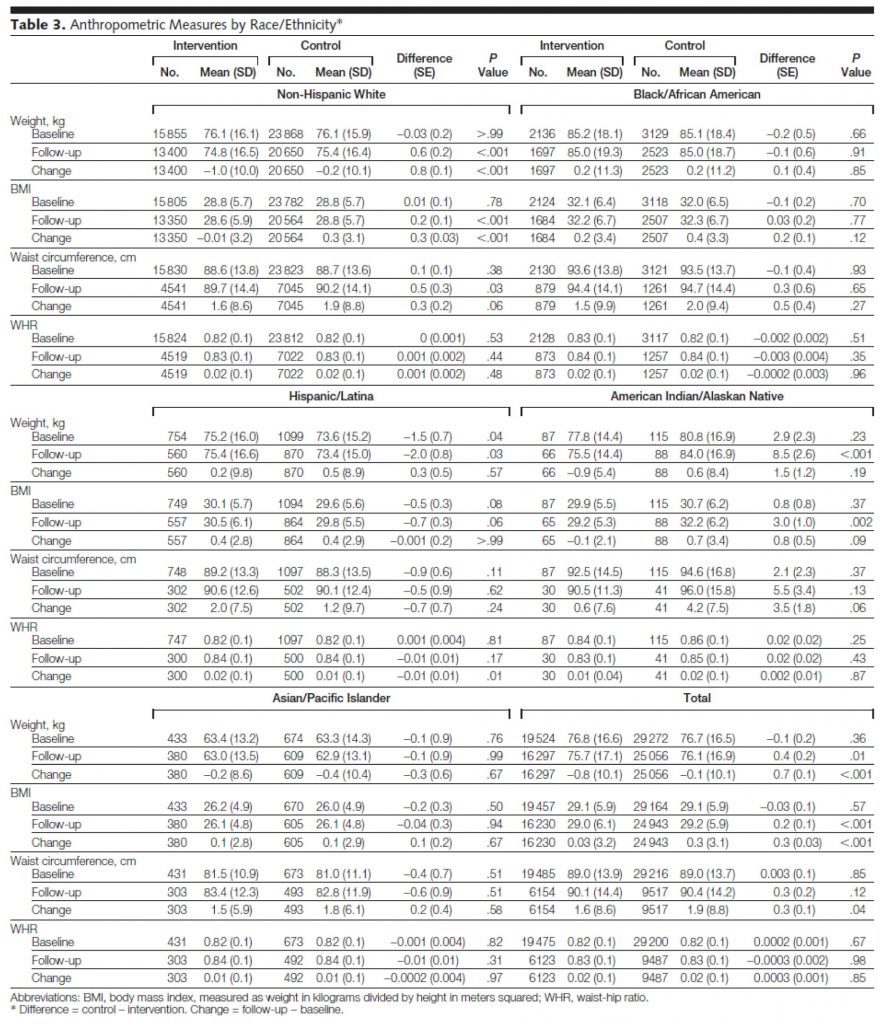

I’ve written before about the difference between statistical significance and statistical power, so I won’t repeat the explanation. But, I’d like to point out the problem of looking at endpoints that were not powered. The largest study included in this BMJ meta-analysis was the Women’s Heath Initiative (WHI), a study of nearly 50,000 post-menopausal women. The WHI, which I talked about at length in the presentation in this post, tested a low-fat dietary intervention over an average follow-up of nearly 6 years. The study was powered to detect hard outcomes like cancer incidence, heart attacks, and death. That’s why the study was so large. But when a study is this large, it’s actually quite easy to find statistical significance in any number of parameters, even if they are not clinically significant or relevant. Look at Table 3 from the JAMA report of the WHI:

You’ll notice that in waist circumference, for example, some of the subsets showed a statistically significant difference. Overall (bottom right section of table) the control (normal fat) group increased their waist circumference over the study from 89 cm to 90.4 cm, while the low-fat intervention group increased from 89 to 90.1 cm, a difference of 3 mm, which achieved a p-value of 0.04. While this is statistically significant (and therefore included in the BMJ paper as a study for consideration), it’s not really clinically significant. In fact, it’s not clear if any of the statistical differences in the WHI are clinically significant. Waist-to-hip measurements didn’t change, which of all the anthropometric changes is probably the most relevant to consider (absent actual body composition data).

Interesting side-note: both the treatment and intervention group lost a bit of weight, yet both groups saw an increase in BMI, suggesting they got shorter over the duration of the study. Furthermore, despite scrutinizing this table and the paper for longer than I care to admit, I cannot for the life of me explain the arithmetic. The authors logically define “change” as the difference between follow-up and baseline. However, examination of this table reveals the arithmetic to be incorrect more often than it is correct. Some instances may be attributable to rounding errors and significant figures, but many are not. It is possible drop-out accounts for this, I suppose.

My micro point

Notwithstanding the fact that the WHI suffered from performance bias:

“Women assigned to the control group received a copy of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans as well as other diet- and health-related educational materials, but otherwise had no contact with study dietitians. In contrast, women randomized to dietary intervention were assigned to groups of 8 to 15 participants for a series of sessions structured to promote dietary and behavioral changes that would result in reducing total dietary fat to 20% and increasing intake of vegetables and fruit to 5 or more servings and grains (whole grains encouraged) to 6 or more servings daily.”

The differences observed, despite this bias, were statistically significant because of the sample size, but were not clinically significant.

My macro point

A meta-analysis based on studies like this is not the best way to answer the question at hand. Sadly, I suspect, most providers (e.g., physicians, dietitians, nutritionists) may not appreciate this given how the media reports on this kind of publication.

Photo by Beatriz Pérez Moya on Unsplash

114 Comments