This week an article titled Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet was featured in the New England Journal of Medicine. The study received a considerable amount of attention, including an article in the NY Times.

Study design

The objective of this study, as its name suggests, was to study the impact of a Mediterranean Diet on the primary prevention of CVD. Primary prevention of X implies looking at patients (ideally those susceptible to X) who have not yet had X to see if your intervention prevents X. Such trials are more difficult (i.e., larger and more expensive) than secondary prevention trials because in secondary prevention trials you start with patients who have already had X and are therefore at much greater risk of having X again.

Let’s use a relevant example. A primary prevention trial for CVD would study subjects who have never had a heart attack or stroke, and look for which treatment (e.g., a drug like a statin) reduces the number of such events (sometimes called MACE – Major Adverse Cardiac Events). A secondary prevention trial would study subjects who have already suffered some MACE and look at interventions to prevent a recurrence.

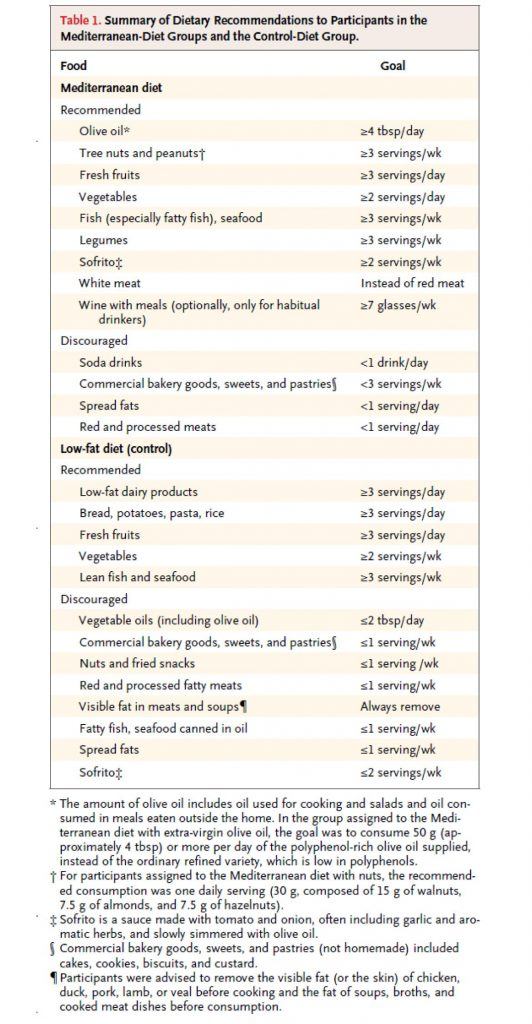

This study, a primary prevention trial, enrolled about 7,500 patients who were at high risk for CVD, but who had not suffered any MACE, and randomized them to one of three diets – two variants of a Mediterranean Diet, and a low fat diet. Table 1 shows the dietary targets. The two variants of the Mediterranean Diet were (i) one that emphasized extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) and (ii) another that emphasized nuts.

(As an aside, my 40th birthday is coming up soon and my wife suggested to my daughter that they make me a cake for my birthday. My daughter – who loves cake, of course – objected immediately by saying, “Mommy, we can’t do that…Daddy hates sugar!” A few minutes later she came back to my wife and said, “Mommy, wait, I have a great idea…we can make Daddy a nut cake!” Those of you who read this post may recall the last point I made. Suffice it to say, if I were in this study, I would have done really well on the nuts arm, though I think I eat closer to 5 or 6x the amount they were recommended per day.)

As you can see all three arms were discouraged from consuming bakery goods, sweets, pastries, red meat, processed meats, and spread fats. The authors report compliance data, but not biomarkers (if I wasn’t so short on time, I’d go back and read the other publications of this study which likely show biomarkers – e.g., insulin, glucose, HDL-C, and triglycerides – which are pretty good for confirming compliance, especially HDL-C).

So, macro point #1 is this:

Everyone in this study, almost by necessity, was consuming a very healthy diet relative to their baseline diet (if you believe most folks were on a “standard” diet, or worse yet, a poor diet, prior to enrollment, which I do). I’ll come back to this point later, but it’s worth remembering this as you read on.

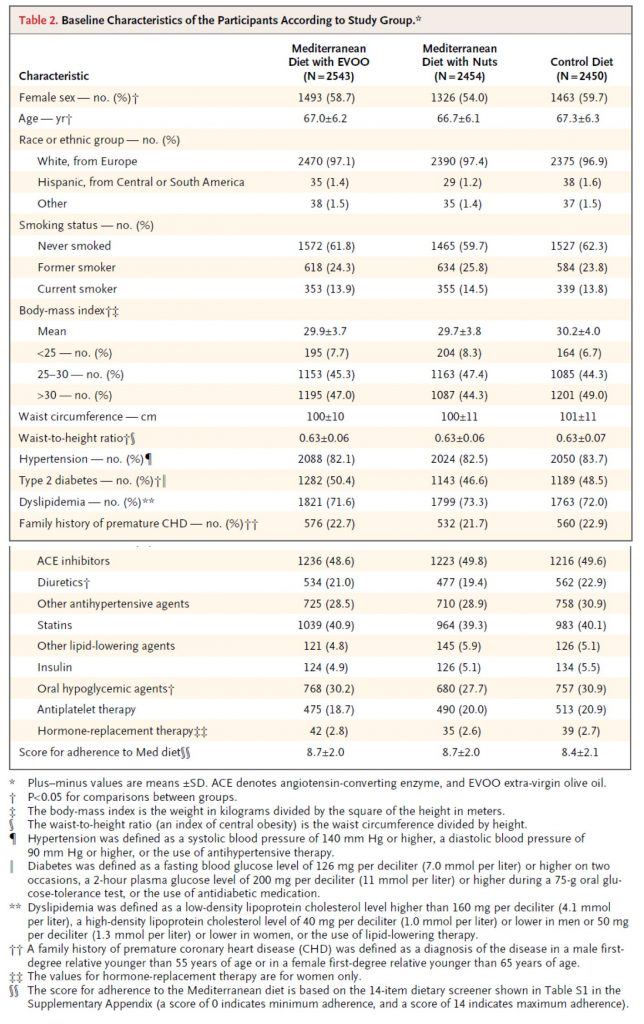

Table 2, below, shows you the baseline characteristics of the subjects in each arm. I must admit, before I saw the results of trial, but knew it was going on, I was a bit surprised at how audacious the investigators were. Primary prevention trials are really challenging! However, as soon as I read the inclusion criteria and saw this table I realized this wasn’t really a garden variety primary prevention trial, per se. Why do I say that? Less than 10% of the subjects were of normal weight. Less than 20% did not have high blood pressure. 50% had type 2 diabetes. Less than 30% had normal lipid profiles (presumably defined by LDL-C and HDL-C cutoffs). Over 40% were taking statins. You get the point. Virtually everyone enrolled in this study had metabolic syndrome.

This is not a criticism of the study, to be clear. It’s merely a statement of why this study, I believe (and hopefully will make a case for), showed a treatment effect in the setting of primary prevention with a dietary intervention. In fact, this is exactly what the authors sought in the enrollment. They specifically looked for high risk patients who had not yet suffered a MACE. In my humble opinion, this was a very good choice for two reasons:

- If they selected healthy subjects, they would have needed 5-10x the number of subjects, and

- This patient population is in desperate need of dietary intervention.

So, my only minor critique of this is the semantics of calling this a primary prevention trial. It would be more accurate to call it a primary prevention trial of patients with diagnosed metabolic syndrome.

One thing I always look for in dietary trials (and trust by now you’re also looking for) is something called performance bias, which is very common in dietary intervention trials. In fact, you’ll recall it was the main flaw of the meta-analysis I wrote about a while ago. The authors of this particular study (you can read about this in the methods section) did a good job avoiding this.

This brings me to macro point #2. This study would have been better if the “control” arm (in this study, the low fat arm), was actually a true control relative to the “standard” patient diet. For example, this might look like the following 3 arms: standard fare diet vs. low-fat diet vs. Mediterranean diet (pick one of the 2 from this study). The drawback of this approach is that patients in the “standard fare” would almost certainly have a performance bias working against them. The other two groups would have a sizable intervention effect, while this (true) control arm would be left on their own.

The final point I want to make is more of a so-called teaching point. Broadly speaking, there are two (and an emerging third) types of studies in human nutrition:

- Efficacy studies – studies that elucidate (under the strictest most controlled conditions ever used to study humans) the mechanism of action of food. In other words, these studies ask, “How does factor X or factor Y actually work at the mechanistic level in the body?”

- Effectiveness studies – studies that elucidate to what extent free-living people will adhere to a dietary change, and determine the long-term safety and effectiveness of that change. In other words, these studies ask, “Does this dietary intervention work over time, and what are the risks and benefits?”

- Econometric studies – studies that elucidate (under free-living conditions) how to change people’s behavior, by changing the defaults, the economic forces, and the cues. In other words, these studies ask, “How do we induce people to change behavior – to eat healthy — once the science provides definitive answers about what that behavior should be?”

Obviously, this study is in the second category, as virtually all “diet studies” are. I mention this for the reason that while it’s tempting to speculate on a mechanism of action in this study, there was not a single design element in this study to elucidate such things. So, at best, we are really looking at the difference between two dietary interventions.

What happened in this study?

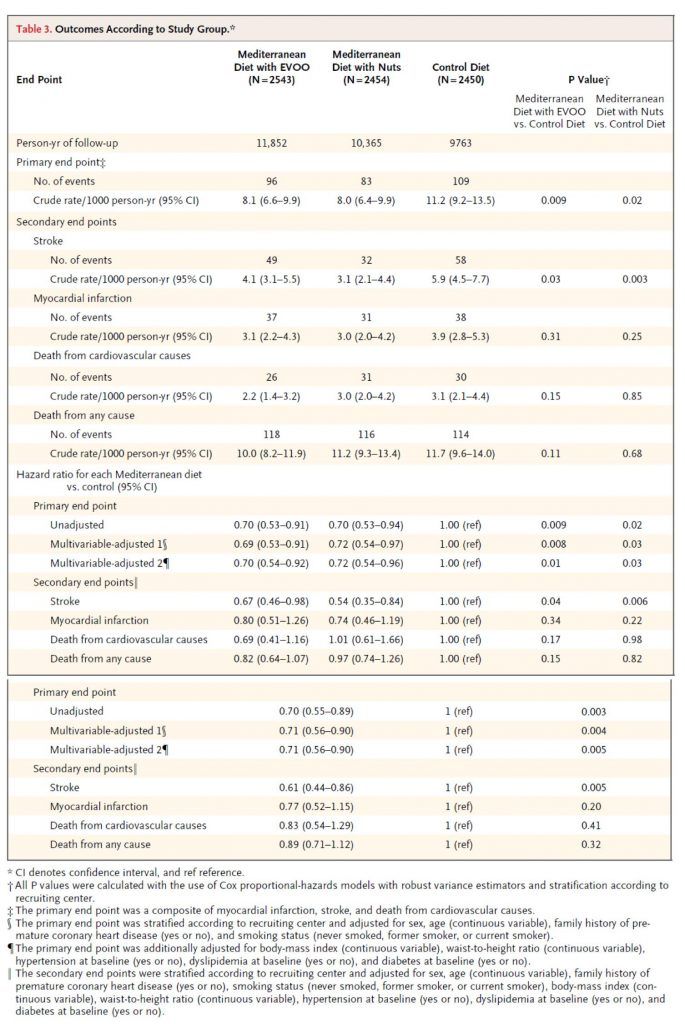

Table 3 shows the outcome of the study and commensurate hazard ratios. I won’t walk you through this table in its entirety, but I’ll show you how to read one row of each.

Consider the first row, the primary end point (recall: this was defined as a composite of myocardial infarction (MI, “heart attack”), stroke, and death from cardiovascular cause). The first row shows the number of crude events. Of course, to see this in an apples-to-apples fashion the number needs to be normalized to a common denominator, in this case events per 1,000 person-years. So, the row that’s particularly important is the one that shows 8.1, 8.0, and 11.2 per 1,000 person-years. (Note, one uses person-years to also normalize for and remove any impact of time in study.) Next to each number I’ve listed above are two numbers in parentheses. These are the 95% confidence intervals. So, even though the first is listed as 8.1, you can be “95% sure” the actual number is between 6.6 and 9.9.

How can you tell if this is “statistically significant?” Most of us don’t possess the ability to do this in our heads. So, the authors do it for us in the last two columns. The right-most column compares the control (low-fat) to the Med Diet (nuts), while the column to the left of that compares the control group to the Med Diet (EVOO). The number shown, called a p-value, is defined as the probability the difference you’re seeing is due to chance. The smaller the better, and generally a number below 0.05 is considered to earn the moniker “statistically significant.” (Not to be confused with “clinically significant,” which I’ll discuss below).

Before we go back to the other endpoints, let me comment quickly on the hazard ratio for this endpoint. A hazard ratio is essentially the probability of an event in the treatment group divided by the probability the same event occurs in the control group (hence, control groups have a hazard ratio of 1.0).

So, the hazard ratio of 0.70 means there was relative risk reduction of 30% for the Med Diet relative to the control diet. This should not be confused with absolute risk reduction, which I’ll get to shortly. For the sake of time and space, I will not go into the details of unadjusted and multivariate adjusted analyses.

But there was no difference in MI or death?

As you can see from Table 3, there was no statistically significant difference in death (CVD or otherwise) or MI across the three groups. It’s very tempting to make the following mistake:

“Hey, none of this matters, because you won’t live longer.”

Remember that pesky little statistical thing called power. This study was powered (at 80%) to detect a difference in the primary outcome, which it showed. In fact, the intention-to-treat was greater than 7,500 because the authors expected no more than a 20% relative risk reduction. But they saw a 30% difference, and the study was halted early.

So, we don’t actually know which of the following statements is correct:

- This dietary intervention does not result in a difference in MI or death; or

- It does, but this study was not large or long enough to detect it.

Very important distinction. I can’t emphasize this enough.

Back to absolute versus relative risk

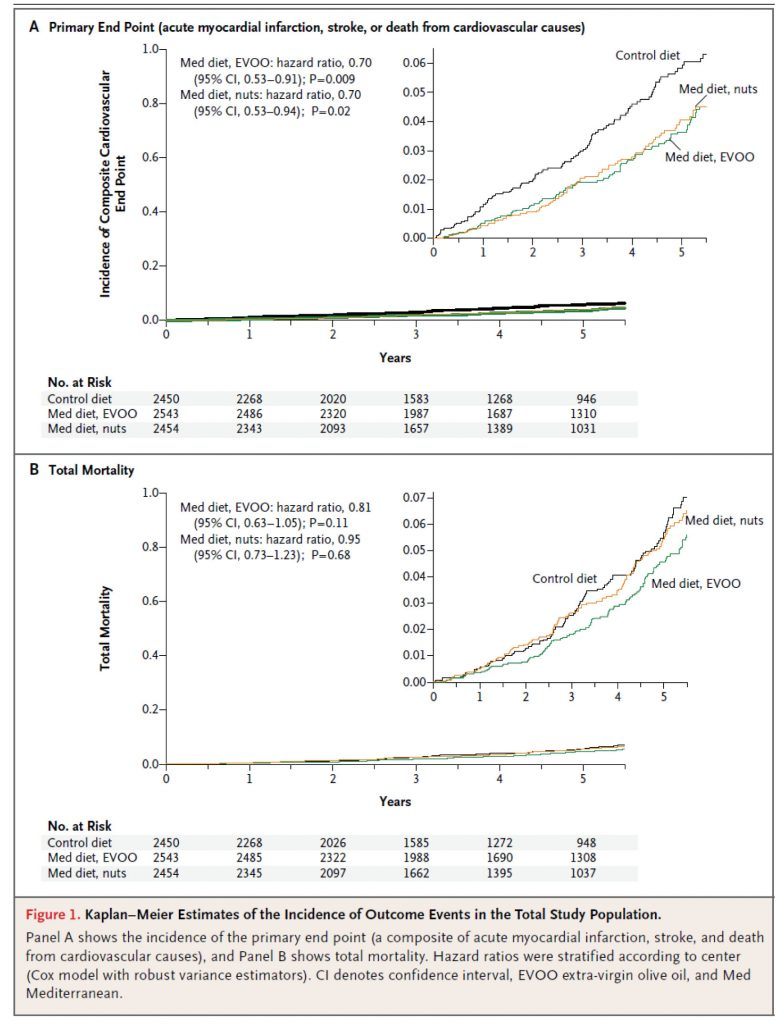

Figure 1, below, shows the Kaplan-Meier estimates for the primary end point (A) and total mortality (B). Each figure shows both the full y-axis (which always varies from 0 to 1) and, in the upper right corner, a zoomed view to show the difference. The fact that the zoom view is necessary tells you something about the absolute risk reduction. It’s small.

Here’s a quick calculator to determine the absolute risk reduction (ARR). When you plug the numbers in from this study (I’ll just do it for the low-fat vs. EVOO group), you’ll see the ARR is 0.3065%. The reciprocal of this number is 1/0.003065 = 326. This is called the number needed to treat (NNT). This means that 326 people would need to undergo this dietary intervention for about 4 or 5 years to prevent one “count” of the primary outcome.

Is this important? Or, to be more specific, is this “clinically significant” as I asked earlier? Well, it depends on the intervention. If this study were testing a drug with a 1% major toxicity rate, the answer would be emphatically, no. Obviously, we could not justify treating 326 people to save 1, if 3.26 people (on average) will experience a major toxicity!

Conversely, if this study were testing a drug with a 1% minor toxicity rate (e.g., headache) and a 0.001% major toxicity rate (e.g., kidney failure), the answer is not so clear. For perspective, most drugs fall into this second category (e.g., statins, aspirin).

I could go through the exact same argument using Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY) instead of toxicity. While this approach is not used in the United States (perhaps it should be), it is certainly the cornerstone of other healthcare systems, such as the NHS in the United Kingdom.

While it’s beyond the scope of what I wanted to write about today, the key to sorting through this grey zone is better defining patient susceptibility and outcomes in large clinical trials. For example, I would argue that the data on statins could be much better if the treatment target was LDL-P or apoB instead of LDL-C, especially in high risk patients with metabolic syndrome, at least half of whom have discordant LDL-P and LDL-C.

So, what to make of the modest ARR in this study? Well, question 1 should be: what is the toxicity of a Mediterranean Diet? Question 2 should be: what is the QALY impact of a Mediterranean Diet?

I can’t really answer either of these questions. The former is objective but has not been quantified to my knowledge. The latter is subjective, and each person needs to answer it for themselves.

My conclusions

Overall, I think this is a good study, and a better study than the study prompting it, the famous Lyon Heart Study. That said, I would have much preferred to see only one Mediterranean arm (in retrospect this is obvious, of course, given the lack of difference between them), in favor of a true control or another arm such as Very Low Carb.

It’s impossible to guess what the ARR would have been for the Med Diet if the control was a standard fare diet (complete with 138 gm per day of sugar!), rather than a much improved low fat diet. If I had to guess, I’d ballpark the ARR at 1-5%, for a NNT of 20 to 100 people, but this is nothing more than speculation. Remember, I think the Low Fat arm in this study experienced an enormous benefit over their baseline.

In the coming months and years, as NuSI begins funding remarkable clinical trials, we’ll have plenty more to discuss…

Photo by Carlos Santiago on Unsplash

Thanks for this overview. CNN’s Sanjay Gupta has criticized the compliance rates in the control, which he suspects produced the differences in outcomes. Any thoughts on this?

Certainly possible, but we’d need more data to evaluate that claim. This is where the full biomarker panel would have been helpful.

This study does not evaluate a Mediterranean diet.

Look at the supplement, S5 table, at 5 years and note the reported composition of diets. The only difference between the arms: more nuts or EVO, and they were given for free, in unlimited supply. Not a bad thing, but title of paper should reflect intake, not “Mediterranean.”

Brad

Interesting point. What do you think accounts for the difference between the Med Diet and the LFD?

I am Italian and we eat lots of red meat… My granddad used to say “you never throw away anything from a pork”.

I believe lot of those “experts” who “created” the Mediterranean diet myth have the classic prejudices of the misinformed dieticians, such as “less meat more fish” and the likes.

Mediterranean diet is a myth because there is nothing such as a “Mediterranean diet”, there are just points in common between different populations living near the sea such as fatty fish, etc., but the rest is a massive mix up of overlapping cultures. Think about the sweets made in Sicily, which are mostly done without sugar but with honey and nuts – this is the typical Arabic cousins, which you also find in parts of Spain, and reflect Arabic domination on those regions. Or pasta, which is massively produced only after the 50s – Italian cultural food goes back much, much more and includes lots of typical cheeses, salamis and so on.

I believe companies like Barilla and the likes have also lots of influence in defining what “Mediterranean diet” is – pasta is not a tradition in the majority of Mediterranean regions, Cous Cous is. Or in North Italy polenta is used instead. Think again about Greece and the sheep’s feast they always make…

Nearly every village in Italy – and I’ll bet in the whole Mediterranean region as well – has local traditional plates. At best “Mediterranean diet” is a very reductive classification, and at most is just a very unjust prejudice.

It is the same misconception that many spreads about Indian cousins being “vegetarian”, when you examine closely they eat very differently in the north and south and they eat lots of lamb and chicken.

When we try to classify traditions we should be looking very closely at the history and not use common places.

Regards

Excellent points, Marco. Thanks very much for insights.

But didn’t the authors say that the “low fat” group didn’t actually reduce their fat very much? It may be that this arm is something not too far from the SSD (Standard Spanish Diet), especially since all of us, Spaniards included, have been bombarded with anti-fat dietary advice for years now anyway. And isn’t the SSD likely to be pretty different from the SAD?

Also, even if we believe the results (not clear to me if we should with such a tiny absolute risk reduction and the many biases and confounders that could be at work), couldn’t it be that the benefit of the “Mediterranean Diet” really came from, say, just increased fish consumption, or decreased sugar, or some other individual factor? It’s not clear to me how one can interpret the results of such a poorly controlled intervention.

Possible, it also may reflect how hard it is to change your diet in a free-living environment, even in the face of a diet “prescription,” right?

Peter, glad to see you back. When I first read it I thought your daughter said you were a “nut case”! I read a Dean Ornish critique of this paper and he was carping about the fact that the low fat arm of the experiment wasn’t low fat enough (for him anyway), thus you can’t derive anything from the study, and from his perspective that is probably true. From my perspective his diet is so drab, boring and unappealing that no one (other than a zealot) could follow it for very long. I wish they had left one group eating their standard diet, and like you said have a HFLC arm.

Dave, I never went anywhere! I’m here working harder than ever (just not on the blog and instead on NuSI).

FWIW.

Dean Ornish’s comments from the NEJM’s Comments section:

Flawed Study: Control Group Was Not Eating a Low-fat Diet!

This study is highly flawed:

• The control group did not follow a low-fat diet. The authors wrote, “We acknowledge that, even though participants in the control group received advice to reduce fat intake, changes in total fat were small.” This is not surprising since they gave the control group little support in following this diet during the first half of the study.

In the “low-fat” group, total fat consumption decreased insignificantly from 39% to 37% (Table S7, appendix). This is much higher than the American Heart Association guidelines of a low-fat diet (<30% fat) or ours for reversing heart disease (<10% fat).

• There was no significant reduction in heart attacks, death from cardiovascular causes, or death from any cause. They only found a significant reduction in death from stroke (Table 3). They only found a reduction in cardiovascular causes when these were pooled with deaths from stroke (Table 3).

The conclusion should be, “We found a significant reduction in stroke in those consuming a Mediterranean diet when compared to those who were not making any significant changes in their diet.”

Dean Ornish, M.D.

Clinical Professor of Medicine, UCSF

I’m sorry, but your conclusion is simply wrong. At the age of 61 I had a surgical intervention (angioplasty with 2 stents inserted). I began the Ornish diet immediately after. About 4 years later I had an angiogram (necessitated by the bias between 2 different scanners) which showed that in fact my arteries had improved. I have maintained this improvement since, as confirmed by an angiogram 1 year ago. In October, 2013 I’ll be 75. The last 7 years I have mainly maintained the Ornish diet except that I have augmented it with EVOO. I live in Italy for 6-8 months a year in a region (Abruzzo) where high quality EVOO is readily available. I take lipitor (10mg) because my LDL is in the low 30’s. So I eat a Mediterranean diet, which includes pasta made from real durum wheat, and which in most respects reflects the Ornish diet. I respect Dr. Ornish, even if I think he’s sometimes a little too defensive about small deviations from his diet.

I was not as impressed as you with this study. Buried in the supplementary appendix is a table showing what the members of the three arms actually ate, as well as the biomarkers gathered.

So how much fat did the MeDiet group eat at the start of the study? 39%. And the low-fat group? 39%.

That’s odd. What about at the end of the study? Mediet: 41%. Low-fat: 37%.

Now as much as I’m in favor of a high-fat diet personally, I find it really hard to believe that changing your fat intake from 39% to 41% is going to have much of an impact. Or reducing your carb intake from 41.7% to 40.4%, as the MeDiet group did.

What really stood out was that the three arms were eating almost identical quantities of everything. The only notable difference was that the nut group was getting more of the fats that one gets from eating a lot of nuts. Shocking, that. Even the fatty acids that come from olive oil were nearly identical across the three groups. Clearly the low-fat group wasn’t listening.

So I’m a little unclear on what this study is actually showing. It certainly wasn’t comparing a low-fat diet to a Mediterrean diet. The best you can say about it was that the MeDiet had three arms, and no control. (The low-fat group increased its olive oil consumption from 15.8% to 16.4%. This was the group counselled to *avoid* olive oil, mind.)

So as partial as I am to studies that show the inferiority of a low-fat diet, this one didn’t do it.

(The biomarkers were to show that the subjects ate olive oil or nuts, that’s pretty much it. Compliance was good.)

Maybe, as some have commented, a LFD in this culture is convergent with Med Diet? I wonder, though, what accounted for the separation? Was something in the EVOO and/or nuts that made the difference?

This was not a a diet that anyone in “this culture” would ever eat. Both arms were advised not to eat too much fat, the diet was designed by fat-phobic dieticians, not from shipping off the Med wing to Tuscany or Athens.

“In the Control group, advice on vegetables, red meat and processed meats, high-fat dairy products, and sweets concurred with the recommendations of the Mediterranean diet, but use of olive oil for cooking and dressing and consumption of nuts, fatty meats, sausages, and fatty fish were discouraged.”

Frankly, having gone through the dietary composition, I can’t for the life of me figure out why one wing might have done better than the other. It may well have been dumb luck, as I just don’t think that minor differences in macro- and micronutrients are going to make much difference.

Olive oil arm: 22.0 % of daily energy from Olive Oil

Nut arm: 17.6 % of daily energy from Olive Oil

Control: 16.4 % of daily energy from Olive Oil

That 5.6% difference must be pretty important…

It may have been something else, also. The fat numbers they report for their fat subtypes don’t add up to total fat. Maybe the third intervention arm was chugging down the trans fat? That could easily cause a difference as small as what they report.

I suspect that if they’d just left the Control group alone, they would have seen a much bigger difference in the result, although I can’t help but think that if anything explains the difference in the Control group, it was that they did not get this advice:

“Negative recommendations are also given to eliminate or limit the consumption of … carbonated and/or sugared beverages, pastries, industrial bakery products (such as cakes, donuts, or cookies), industrial desserts (puddings, custard), French fries or potato chips, and out-of-home pre-cooked cakes and sweets.”

That’s pretty good advice for anyone! But again, how is avoiding “carbonated and/or sugared beverages” low-fat?

Thanks for your quick analysis, Dr. Attia. I was eager to hear what you had to say about this study. Keep up the good work. We are all looking forward to the results of NuSI funded research.

The fact that this study has gotten such good coverage is a good indicator that the media is ready to talk about alternatives to the standard-issue medical guidance that a low-fat diet is best. That said, they’ll still have a problem with things like grain and sugar elimination.

As to the low-compliance on the low-fat branch of the study, that speaks for itself. Not only is low-fat a poor choice, it’s so hard to follow that the medical consensus that diets don’t work.

Peter,

Totally agree that it would have been nice for them to have included a different group, either “standard” diet or very low carb. In fact, the way they designed it, it almost seems like they had a foregone conclusion that some Med diet would be better, question was only which would be preferrable. From this study, I only conclude that a diet higher in fat resulted in reduced cardiac events (consistent with results of Ludwig and other recent studies), but the study does absolutely nothing to disentangle which kind of fat or if kind even matters. As for me, I’ll happily stick with red meat, cheese, eggs, and whole milk… seems to work for me!

Personally, I find this study to be complete garbage. For instance, assuming the people followed the recommendations, the high oil group was supposed to eat at least 4 tbsp of oil per day, while the low fat group was supposed to eat less than 2 tbsp per day yet eat much higher amounts of bread, potatoes and other carbohydrates. How can you tell the minimal benefit in the high oil group wasn’t due to the differences in carbohydrate content between the two groups (the high oil group and the low fat group)? There are so many variables they changed you have no idea what’s causing what. Is it the oil that’s helpful? Is it the 7+ glasses of wine per week? The amount of vegetables eaten (2+ servings per day versus 2+ servings per WEEK)? It’s ludicrous. That this is classified as “science” (and that they stopped the study due to the purported benefit) is sickening.

Fair point, Bob. But remember the difference between an efficacy study (what it sounds like you’re after) and an effectiveness study.

Bob, Just want to emphatically concur… this study is “complete garbage.” On the sole basis that the the “control” group asked people to consume >3 servings per day of carbs including bread, pasta, and the study group was told to avoid bakery goods, it would have been equally valid for the study to conclude that bread and pasta cause heart disease (a-la Dr. Davis). But per the other points about the study design, I don’t think it can even claim that either.

I think it’s a very poor statement about the state of peer review that a paper like this could make it to press making the claim it did. And sorrier still that the popular press didn’t spot this right away. You don’t have to be a diligent sleuth like Denise Minger to spot this fatal flaw.

Hi Peter,

Nice post, and thanks for the statistical insights.

I think it was a very well done study too, but one thing that stuck out at me was that none of the study participants got healthier. That is, after 5 years people in all 3 groups were taking more prescription medications than they were at baseline. In other words, I don’t think any of the diets were optimal for this high risk subject population.

Best regards,

Bill

Very interesting point, Bill. Certainly suggests there is room to improve in all arms.

Hi Peter!

I love your blog, I think I have read every one of your posts!

I was googling and ran into a few posts and studies on palmitoleic acid and omega-7s. I would love to hear your thoughts on the subject. Perhaps an idea for a future post?

Kelcy

Well, I guess it depends on your question. Palmate is a SFA that is created during de novo lipogenesis.

Peter

Great analysis. Question/comment…. Marco point one emphasizes how the study included subjects with metabolic syndrome. You comment that healthy individuals did not predominate. This may be true but how much do the subjects in this study represent an unbiased cohort of spain or america? ie Sure all these people had metabolic syndrome but isnt this what we are dealing with here in the US?

Great question, Ted. In the US, 37-39% of the population is obese. Of this group, about 66% have MetSyn. Conversely, 31% of the US population is “below or normal weight” according to the latest stats, and about 7-9% of them have MetSyn. So obesity is really just a (very good, but far from perfect) proxy for MetSyn. So, I think this population is good representation for the (sadly not small) segment of the US population most at risk for metabolic diseases.

According to the latest AHA statistics (2012), quoting NHANES II or III, more than 46% of americans have either frank diabetes or impaired fasting glucose. When you consider that insulin resistance tends to manifest in elevated blood sugar LAST among its many manifestations, that means that well over half of the population likely has metabolic syndrome (insulin resistance syndrome, carbohydrate intolerance, or syndrome of increased waist circumference, elevated glucose, elevated blood pressure, depressed HDL, increased triglycerides). Therefore, primary prevention has now become all about the treatment of metabolic syndrome and its legacy.

Very, very important point, Dan (and Teddy). Thanks for raising.

Thanks for the interpretation of that study, Peter.

I think you have your work cut out for you on NUSI, based on my doctor’s reaction to my yearly checkup today.

I told him I wanted the NMR LipidProfile Test done, and he got angered at my request, and refused to write a script for a lab test.

I then told him that my mother passed away from MI the day after her doctor told her that her bloodwork was fine.

He said that God wanted to take her.

Then I told him about the low carb/high fat diet I was on for the last eight months, and he asked if I could name him as my beneficiary, because I was going to be dead in a very short time.

I then told him that I thought I was insulin resistant, because I was on a low fat /high carb diet for the last twenty years, but I was still overweight for my height and body frame.

He said if I was insulin resistant, I’d be diabetic.

I then said that I probably had metabolic syndrome, and he said that it didn’t exist.

Then I told him I lost 20 lbs. on the diet, and eliminated my sugar cravings, and he just ignored that.

I asked him again for the NMR Lipoprofile Test script, and he said he was giving me a Lipid Profile Test to measure LDL-C, and that LDL-P is nonsense, and has no bearing on cardiac health.

I started to mention your website, and he got extremely angry, and said he wasn’t interested in some nut with a website had to say that contradicted years of scientific work by reputable doctors. He then told me I was suffering from the new DSM classification of “Internet Hypochondria”.

At this point, he started to use some four letter words that might not be appropriate on this blog, and turned his back on me, and I realized my visit was over.

Another story from the Naked City (NY)!

I normally would not speak so candidly, Stephen, but I’m sure others reading this will agree…you need a new doctor. This person, if for reason other than their arrogance, has no reason to be practicing medicine.

Stephen, I asked Peter something similar some time back. I had a Dr. who I educated about this new Lipid test, but she was bound by certain rules in helping me any further for my LDL-P issue. Peter referred me to the Jimmy Moore website as he has a listing of Low Carb Dr.’s. Here is the link: https://lowcarbdoctors.blogspot.com/

There are several Dr’s to chose from in NYC. Your current guy seems to be living in the past where Dr’s patronized you and patted you on the head and told you what was best. Well the Internet is here now and that is both a good and bad thing when it comes to health. I think highly of the information on this site, however, it is sometimes hard in a sea of health websites to find what is true or likely to be true vs. total BS. Even among the Low Carb community there are various points of disagreement, but in general they agree more than they diverge. Everyone has some degree of selection bias, I just like to think there is some data behind mine. Good luck finding a new physician.

You definitely need a new doctor. There are a couple of lipidologist websites with a search feature; some of the doctors are cardiologists and primary care physicians: lipidboard.org and lipid.org. Jimmy Moore mentioned on a podcast that he gets his labwork through privatemdlabs.com. I just checked, and they have the NMR for $125. Best wishes, maryann

Very interesting trial. Hard to get such a study funded in this environment (Pharma is completely disinterested in this, for obvious reasons). Fantastic that the results were achieved in an environment in which nearly two thirds were on LLA’s and >80% on AHT’s. I think that the dietary differences were more significant than can be appreciated in that technical appendix, and probably the INTENSITY of dietary counselling (especially regarding trans fats and PUFAs) is what drove the difference. The effect size is about what you would expect for statin in this population and about double what you would expect for aspirin in high-risk primary prevention. That it occurred on top of what looks like optimal medical therapy is quite gratifying.

Personally, it will not change much my approach to dietary counselling – minimization of acellular carbohydrates, maximization of healthy plant-based fats and oils – in fact, that is what they recommended in this trial, rather than a true mediterranean diet (which is very high in carbs).

Everyone is always touting olive oil. It would be nice to see a study that compares it to other lipids, both SFA’s and other MUFA heavy fats like lard, avocado, etc. Do they know what in particular is the healthy part of olive oil? Is it the MUFA or polyphenols or other?

Also, is this statement in the comments section of the NYTimes article true?…

“this was not an independent peer reviewed study. The funders were the olive oil and nut companies.”

Brad, to your first point, there is a very interesting paper coming out, probably in the NEJM, probably before summer, that shows some interesting benefits of EVOO.

To your second point, not correct. The olive oil and nut companies, which provided food for free, neither funded, nor ran the study.

Or course, the challenge with olive oil is the degree to which it’s adulterated. Have a look at “Extra Virginity” by Tom Mueller. It’s made me a LOT more careful about where I buy my oil.

I think the Mediterranean diet has a great balance to it and is not too restricted. Great in depth article.

Superstar worthy analysis Dr. Attia-well done! I’d love to compare and contrast gut microbiota when altering the diet in future studies. Fingers crossed. Best, SM

There will be much to discuss…

The doctor-patient relationship in the world of information/internet is certainly an interesting issue. It is obvious that doctors have to be better prepared because their patients nowadays have access to a lot of information. Here is an article you might like to read that on the subject of heart disease prevention, diet and drug therapy: https://www.docsopinion.com/2013/03/02/diet-or-drugs-to-prevent-heart-disease/

Follow up piece in the NYT times had this lead in;

“A study (the Mediterranean diet study)has infused the field of cardiovascular medicine with optimism, as scientists are calling for similarly rigorous studies of other popular diets.”

Maybe they should check out your website where they may try ‘even more rigorous studies’.

One of my Board members sent this along with a similar comment today!

I think there is some substance in this so called rumor of Mediterranean diet being very healthy, there are results which prove that. I guess lot of it has to do with olive oil, which is known to be the most healthy cooking medium and this makes all the difference.

I think there should be a comparative study between Olive oil and other cooking medium, then more conclusive results can be obtained.