In this episode, Katherine Eban, investigative journalist and author of Bottle of Lies, illuminates the prevalence of fraud in generic drug manufacturing which brings into question the idea that generics are identical to brand-name drug as we are lead to believe. Katherine walks us through how this widespread corruption came to be, including the shocking story of one particularly egregious (and unfortunately not uncommon) example of an Indian drug company, Ranbaxy, whose business model was completely dependent on falsifying data in their drug applications to the FDA. We then discuss the subsequent investigation into Indian and Chinese drug manufacturing plants which revealed that nearly 80% of them are tainted with fraud. We conclude this discussion on a positive note with i) how individuals can investigate their own drugs to protect themselves ii) an innovative pharmacy attempting to disrupt the market and iii) some ideas on how to reform to the regulations around generic drugs, the FDA, and more.

Subscribe on: APPLE PODCASTS | RSS | GOOGLE | OVERCAST | STITCHER

We discuss:

- How Peter found Katherine’s book, and what convinced her to investigate the generic drug industry [5:45];

- Branded vs. generic drugs: Why they aren’t the same thing [11:15];

- The Food and Drug Administration: Why it was originally created and what it does today [20:45];

- How the generic drug industry really got its start in the U.S., and the flaw of the Hatch-Waxman Act [28:20];

- PEPFAR: How a well-intentioned plan to help Africa with the AIDS epidemic laid the groundwork for corruption [36:30];

- The story of Ranbaxy: An Indian drug company whose business model was fraud and deceit [40:45];

- How the FDA approves drugs, the impact of “first to file”, and Peter’s tangent on moral corruption [47:30];

- A booming generic drug market and the FDA struggling to keep up [57:15];

- Dinesh’s internal investigation finds widespread fraud and falsified data inside Ranbaxy [1:00:15];

- Presenting the famous SAR document to Ranbaxy’s board of directors which spells out the company-wide fraud [1:09:15];

- Dinesh blows the whistle on Ranbaxy which leads to a raid on their US plant [1:19:45];

- Formal investigation of Ranbaxy is launched, but the FDA keeps approving Ranbaxy drug applications [1:33:30];

- What role does the culture in India play in the high prevalence of fraud in the drug industry? [1:41:00];

- The extreme prevalence of data fraud/manipulation in foreign generic drug factories [1:52:30];

- Concluding the Ranbaxy story [2:06:15];

- How concerned should you be when buying a generic drug from your local pharmacy? [2:11:15];

- How to investigate your own drugs for quality to ensure you are getting what you need [2:18:30];

- An innovative pharmacy that tests all its drugs for quality [2:24:45];

- Reforming the FDA and generic drug industry: Why we need reform and ideas on how to do it [2:27:45];

- The importance of taking individual ownership and not waiting for Congress to bail us out [2:34:00];

- Closing thoughts from Katherine [2:36:50]; and

- More.

How Peter found Katherine’s book, and what convinced her to investigate the generic drug industry [5:45]

How did Peter come upon Katherine’s work?

- Sam Harris recommended Katherine’s book, Bottle of Lies, to Peter

- Sam found the content infuriating which got Peter intrigued (since he views Sam as someone who never gets mad)

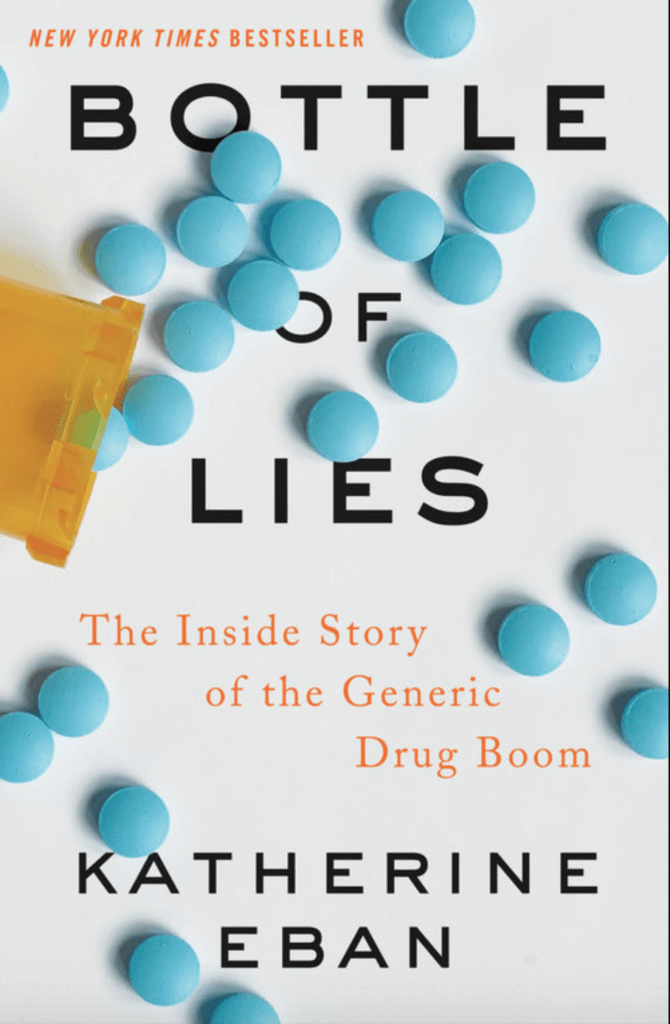

Katherine’s book: Bottle of Lies: The Inside Story of the Generic Drug Boom

Figure 1. Cover of Bottle of Lies by Katherine Eban. Image credit: katherineeban.com

What got her into the topic of generic drug manufacturing?

- “Before I started with this project, I thought about generics the way I think most people do, which is we need them, they’re affordable, nobody can afford their brand name drugs and they’re sort of an engine that makes government health programs run.”

- In 2008, however, Katherine got a call from Joe Graydon (runs an NPR podcast called The People’s Pharmacy)

- He informed her that he had been getting sent a ton of messages from listeners who were complaining about side effects from their generic drugs and/or that they weren’t working the same way that their brand name drugs had been

- Joe took the complaints to the FDA who shrugged it off as all in the patients heads since the drugs had a different name and color, “but the drugs are fine.”

What made Katherine think there was something to this situation that made her want to dig into it?

- As an experienced investigative journalist, Katherine said you develop a sense, a “tingle”, when something seems like a legitimate issue

Branded vs. generic drugs: Why they aren’t the same thing [11:15]

Analogy: Kleenex (brand) vs. facial tissue paper (generic)

*Misconception about generic drugs: Most people believe (because the FDA told them so) that generic drugs are identical to the brand name (just at a lower price point)

How to generics come to be?

-A generic is a version of a brand name drug that is made either after a brand name drug has

- gone off patent so it’s no longer legally protected, or

- if the generic company has successfully challenged the brand patent in court and then the FDA gives them permission to make a generic

But is it identical?

- No

- In fact, if you make two batches of drugs in the same manufacturing plant using the same ingredients, those two batches will be a little bit different

Steps to making a generic (and why it can be different from the brand name):

- A drug company has reverse engineered the brand drug

- So they have broken it down in a lab

- tried to figure out how to put it together

- maybe with a different set of manufacturing steps

- They have then concocted the drug

- However, they might have used additional ingredients as long as the central molecule which has already been tested for safety and efficacy is present

- Then they have to present data to the FDA

- The FDA recognizes there’s going to be differences, so they’ve provided a range

- The range is measured in terms of the absorption of the drug into the blood

- The generic drug company has to present data to the FDA showing through their testing that they’ve hit within that range

- And if so, the drug is considered bioequivalent

But wait…why do the generic companies have to reverse engineer the drugs? Don’t they get the blueprint once the patent expires?

- Turns out…

{end of show notes preview}

Katherine Eban

Katherine Eban, an investigative journalist, is a Fortune magazine contributor and Andrew Carnegie fellow. Her articles on pharmaceutical counterfeiting, gun trafficking, and coercive interrogations by the CIA, have won international attention and numerous awards. She has also written for Vanity Fair, the New York Times, Self, The Nation, the New York Observer and other publications. Her work has been featured on 60 Minutes, Nightline, NPR, and other national news programs. She lectures frequently on the topic of pharmaceutical integrity.

Her first book, Dangerous Doses: a True Story of Cops, Counterfeiters and the Contamination of America’s Drug Supply, was named one of the Best Books of 2005 by Kirkus Reviews and was a Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers pick. Her account of reporting on 9/11 was anthologized in At Ground Zero: 25 Stories From Young Reporters Who Were There. Her work has also been awarded grants from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Fund for Investigative Journalism, the Alicia Patterson Foundation and the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at CUNY’s Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism. Educated at Brown University and Oxford, where she was a Rhodes Scholar, she lives in Brooklyn with her husband, two daughters and Newfoundland dog Romeo. [katherineeban.com]

Jugaad! On the nose.

I disagree. As a native Hindi speaker I can tell you that it reflects a creative process of thinking ‘out of the box’ that allows somebody to use otherwise useless or discarded objects or ideas to innovate and repair a broken item or make something entirely new and hitherto unheard of. Like a the motor in a lawn-mower to power a tractor, or a guy sitting in a small shack in Mumbai repair an iPhone for $10 using spare parts and ‘fixits’ where the original owner in New York would be forced to throw it away.

While Jugaad can also mean ‘do something about it’, there is no ‘sinister’ or ‘dark side’ to its use in a corporate world as Ms. Eban suggests.

I share Peter’s sentiment, how infuriating! However, the solution is not necessarily practicable. Even if I take the first step “to pay attention to who’s making the drug and how it works”, I don’t have the option to get my pharmacy to substitute it or to pick a different pharmacy – the insurance company forces me to use Caremark mail order pharmacy for ongoing prescriptions. Yes, I checked my drug manufacture thru Katherine’s sources – sure enough, they are from India and have had numerous FDA actions. Now what?

Check out the cash prices at Valisure pharmacy or use good Rx and shop around.

Really informative podcast! Would switching from a generic to a brand name Rx be safer? Or is there just as much chance that these drugs are fraudulently manufactured overseas as well?

Good question

Great interview, Eban really knows how to tell a story! I found this audiobook on Scribd. Another good (older) book, on how ^&*ed up drug research can be is Overdosed America by John Abramson (also on Scribd!). Maybe we should expect this from entities/companies whose primary duty is to their shareholders is to increase profits- but what’s most disappointing/maddening is the impotence of the FDA in dealing with it.

Ranbaxy was an endemically corrupt manufacturer that placed making money above the health of the patient. This podcast made it sound like no generic manufacturers could be trusted;which is untrue and misleading.

One of the reasons I am a subscriber is that Peter provides topical information pertinent to me in a balanced, thoughtful and impartial manner. Didn’t happen here!

I found Peter Attia through Sam Harris whose podcasts I subscribe and listen to regularly. I believe Peter is a breath of fresh air in this congested world of TMI. I see that he interviewed Ms. Eban because Sam Harris found her book ‘infuriating’.

While the interview is interesting as a ‘whodunit’ story, it is nothing new for those of us who are in the profession ourselves. The Ranbaxy story is well known and now quite dated. What is equally infuriating to me as an Indian-American is the very obvious anti-India bias exhibited by Ms Eban in her tone of voice, choice of words and selective reporting. I have not read her book, nor do I intend to if it is nothing but more of the same.

Perhaps it is not intentional, but by the end of the podcast it appears to be so.

1. “You had Indian Companies long regarded as fakers and counterfeiters”

2 ‘Throw it in the Ganges’ – not understanding that this is a deeply offensive statement to millions of Hindus.

2. “Generic companies can get around patented products by reverse engineering – Indian companies are just doing that” – so is it just Indian companies or all generic manufacturers?

3. ‘Whistleblowers are routinely killed in India” – this is the most egregious of all her statements. Does she believe that India is a completely lawless nation? She conveniently forgets to mention Roche vs Adams, and that Switzerland – the paragon of virtue and development if her implications are to be accepted – actually has laws against whistleblowers to this day. Adams’s wife killed herself over his arrest. of course it is only Indians who are capable of such horrors.

4. “Amazed that the Indian courts ruled against Singh” – another assumption that the Indian court system is corrupt beyond belief.

5. “The Cheapest generic is likely to be from India” – Why? There are plenty of other ‘poor countries’ making these, why India?

In her ceaseless tirade against one company, by extension she implicates all of Indian manufacturing and the entire Indian culture – that is 1.3 billion people. She never once mentions Teva, the Israeli company that supplies one out of every nine drugs sold in the US and is the world’s largest generic manufacturer, certainly the biggest one selling to the US. Or Mylan (second largest), or Sandoz, who are all bigger suppliers of generics than Indian companies. Does she expect people to believe that only Indians and Chinese are capable of fraud and that none of the top sellers of generics to the US population could be susceptible to the same virus of GREED?

She also forgets to mention the antitrust lawsuit filed by 44 US State AGs against Teva, Pfizer, Sandoz, Mylan and other companies (these four are the top listed) for price fixing. Quoting directly from the 524 page complaint filed in court: “Teva and its co-conspirators embarked on one of the most egregious and damaging price-fixing conspiracies in the history of the United States. ”

By Ms. Eban’s reckoning, 80% of all generics sold in the US come from India or China (not true as I just found out) and four-fifths of these companies were found to have ‘data discrepancies’ (what does that mean anyway). Which means the majority of Americans are probably taking fake or dubious medications. Equally, the majority of Indians in India and the Chinese in China are taking generics, presumably from these same fake companies selling fake drugs. Which means we have a global population of several billion people all taking drugs that either do not work or are harmful. If that were indeed the case, by now we would have had an epidemic of catastrophic and cataclysmic illnesses and side effects the world over. Anecdotally, I myself have been taking generics for years (take six different meds daily) and have not had any issues, neither have most of my patients.

What would have been a great discussion on Big Pharma’s role in the health of the world is the extortionist tendencies exhibited by all these corporations, the bigger they are, the worse it seems to be. Why does Harvoni have to sell for $1000 a capsule? I understand the company has spent a billion dollars on developing a drug, but then does it need to make ten billion from it? There is a crisis of epic proportions coming down the pipes and instead of focusing on the need to have cheaper branded drugs, we have Ms. Eban essentially spreading FUD about the use of generics. In the process she makes a scathing and sweeping indictment of India as a nation and Indians as a people.

Greed is universal and no individual, corporation or nation state is exempt from it, it is only the deviousness that is employed in the pursuit of wealth that is different.

In the end, this podcast raises more questions than it answers.

c

As a person of Punjabi heritage, I was shocked to read ‘Bottle of Lies’. I am ashamed to read about the extent of corruption in Punjabi corporate culture at Ranbaxy. As a kid, I was told by my father and grandfather that what sets the Punjabis apart is our hard work, honestly, and belief in the equality of all human race. This was shattered by reading Katherine’s book.

This is personal. My family has suffered from Indian generic medicine. My uncle was traveling in India and took an Indian-made drug for a cold. He suffered kidney damage due to toxins in the drug. He is on dialysis now.

I am mad at both Indian drug manufacturers and the massive greed of the American healthcare industry. Healthcare in America is a massive fraud. I refuse to take medicines anymore. It is all BS.

Charles Ortel has done excellent work on another fraud, the Clinton Foundation and its role in promoting Ranbaxy’s AIDS medication.

Just search Ranbaxy & Ortel & Clinton Foundation …

Example (Sep 2016):

“Although Ranbaxy’s generic drugs are now barred from being sold in the U.S., CHAI and the former president continue to praise Ranbaxy and distribute the company’s HIV/AID drugs to patients abroad. […] Bill heaped praise on Ranbaxy in 2013 during a speech in Mumbai, saying, the drugs saved millions of lives. […] Neither CHAI nor the Clinton Foundation have announced they severed ties with Ranbaxy.”

Perhaps that’s why it took so long for Rod Rosenstein, Comey et al to get around to prosecuting.

aiP

Culture is most significant factor for corruption. This has changed the DNA of all people in India over centuries.

1. In Sanskrit they say “”Saam daam dand bhed”” it means execute the thing by four Ways.

Daam- Bribe. Dand- Punishment. Bhed – Division. Together, it means (with respect to this phase) – to/towards achieving a means by either by willingness or by acceptance (Saam), or by bribery or corruption (Daam), or by punishment (Dand) or by dividing (Bhed).

2. It’s in blood you can’t change until you born in foreign land or else honest mentoring of young ones.

I really enjoyed Katherine Eban your knowledgeable speaker from Bottle of Lies.

However, I was very frustrated listening as Dr. Attia who continuously interrupted Katherine almost in a bullying way. Katherine was so classy and never seemed annoyed.

I listen to many of your podcasts. It’s rare that you have a female speaker and it strikes me as strange that you don’t treat your male speakers in the same way.

Just an observation.

Dr. Andrea Jack

Toronto

I noticed the interruptions too, but I have a feeling Peter was interrupting mainly for comedic effect. It’s a pretty heavy topic, and I actually appreciated the humor in this podcast. But yeah, generally no bueno to interrupt people and kudos to Katherine Eban for being so accommodating of the interruptions.