Mike Gershon is a Professor of Pathology and Cell Biology at Columbia University and has been at the forefront of studying neural control of the gut for the past 60 years. In this episode, Mike gives a tour de force on the pathways of gut-brain communication but first sets the stage with an overview of gastrointestinal tract development and anatomy. He then explains how the gut communicates with the brain and vice versa, from early observations in physiology and anatomy up to our present understanding of what makes the GI tract so unique and complex relative to other organs. He talks about how the gut responds to meals of different food qualities and how that affects satiety signaling to the brain. Additionally, he explains how antidepressants and other drugs impact digestion through effects on serotonin signaling, and he discusses the effects of antibiotics, and what’s really going on with “leaky gut.” Finally, Mike offers his thoughts on the utility—or lack thereof—of gut microbiome diagnostic tests, and wraps up the discussion by considering how diet, probiotics, and prebiotics impact the microbiome and GI tract.

Subscribe on: APPLE PODCASTS | RSS | GOOGLE | OVERCAST | STITCHER

We discuss:

- The basics of the gastrointestinal (GI) system [3:45];

- The very early development of the GI system [9:30];

- The unique properties of the blood supply and portal system in the GI tract [12:45];

- An overview of gut anatomy and innervation [16:30];

- Turnover of the epithelial lining and why cancer rarely develops in the small intestine [26:45];

- Nutrient and water absorption in the small and large intestine [30:30];

- Ways in which the gut and brain communicate [34:30];

- The gut’s role in the regulation of appetite [43:30];

- The impact of gastric bypass surgery on satiety signals [51:15];

- How varicella-zoster virus (VZV) can infect neurons in the gut and create issues later in life [54:30];

- The relationship between autism and gastrointestinal illness [1:02:45];

- The important role of serotonin in the gut, and the impact of SSRIs on serotonin in the gut [1:09:45];

- Defining “leaky gut” and its most common causes [1:16:45];

- The gut microbiome [1:30:45];

- Fecal transplants: use cases, limitations, and how they illustrate the importance of gut microbes [1:40:45];

- Gut microbiome diagnostic tests: why they aren’t useful outside of special cases such as cancer detection [1:50:30];

- Nutritional approaches to a maintain optimal flora in the gut [1:55:00];

- Prebiotics and probiotics, and getting your GI system back on track after a course of antibiotics [2:02:30]; and

- More.

The basics of the gastrointestinal (GI) system [3:45]

What brought you so much curiosity to study the GI system for 60 years?

- Mike has been studying the GI for 60 years and there’s still more to study; it’s a very difficult subject

“As the saying goes, the further you get from shore, the deeper the ocean gets”‒ Peter Attia

- There is a lot of fundamental foundational knowledge required to have a basic understanding before we can get into the nuanced stuff around the GI system

- It makes sense to start with some of the basics of the human GI including its embryology, anatomy, vascular supply, and ultimately we’re going to want to talk about its connection to the nervous system, which is quite distinct and unique (relative to even the peripheral nervous system)

Characteristics of the GI tract and its function

- The GI system is basically a tube that begins at the mouth and ends at the anus

- It’s hollow so the inside of the GI tract is really an internalized external space; it’s outside the body

- If you bleed into your GI tract, you lose blood (even if you can’t see it)

- This is one of the major crises in medicine‒ hidden bleeding in the GI tract

- It can be very damaging, even if you don’t see any blood

- If you bleed into your GI tract, you lose blood (even if you can’t see it)

- The inside of your gut is outside of your body, and it provides a space for a community of extra organisms to live

- This space is immense

- This space can be dangerous and a barrier is necessary to keep it separate from the rest of you

- This barrier is defended by the body

- It also allows food to be digested and absorbed

- It has to maintain the communication with the lumen, which is what we call the inside of the GI tract

There is a balance in the GI between protection of the body and allowing food stuff to come in

- People understand that many bacteria colonize our nasal passages, skin, etc.

- And that when bacteria enter the body, bacteremia is a bad thing

- The GI tract has unique challenges because it must allow transmission of nutrients across its surface but not allow bacteria/ organisms to go through

- Further, the food we eat is not ready for absorption

- Food has to be digested

- Not only does the gut have to absorb a variety of things, it does so in an awful witches brew that breaks down the food

- All without digesting yourself

“The lining of the gut is absolutely remarkable”‒ Michael Gershon

- Complex molecules that are not sterile are entering a non-sterile environment and somehow only sterile nutritional building blocks are allowed to cross the border of the GI tract

The very early development of the GI system [9:30]

- During development the body forms a flat disc

- That disc undergoes a series of folds from head to toe, and from side to side, and the lateral or side folding produces the tube from which the gut forms

- So the flat disc folds around to create an internal space, and that tube because the gut

- This takes place during the 1st trimester

- The gut is fully developed between the 2nd and 3rd trimester

- The first part of development is called embryogenesis

- That is the fertilized egg forms the disc, the disc folds, the organs of the body form, and that’s the embryonic period

- The fetal period follows

- The fetal period models the organs into their appropriate developmental form so that they becomes functional enough to support a baby

- Peter recalls from med school (26 years ago), that fold turns into the tube which will become the entire length of the GI system, and there are also these little outpouchings that come along later

- These become things like the pancreas and the bile duct, etc. which form other things that drain into the GI system and perform essential functions for digestion

- For example, the pancreas and gallbladder drain into the gut

- The lungs are also formed, and they do not drain into the GI system

- The liver has a component that drains into the gut through the bile system

- The foregut forms the stomach, the first part of the small intestine, the lungs, the pharynx, pancreas, gallbladder

- The midgut is the business of small intestine and the first part of the large intestine

- The hindgut is the end of the large intestine

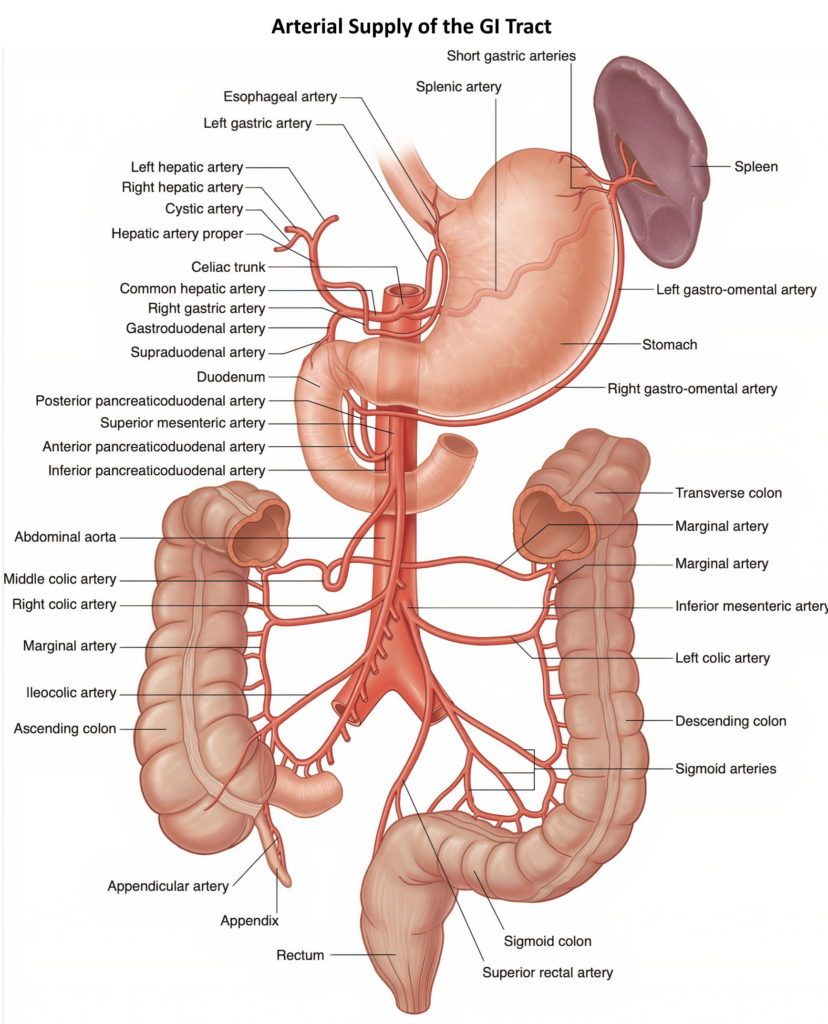

- Peter recalls that the foregut, midgut, hindgut basically tracked with the three vessels coming off the aorta‒ the celiac, the superior and inferior mesenteric

The unique properties of the blood supply and portal system in the GI tract [12:45]

- The foregut is defined as the part of the gut from the celiac artery

- The celiac artery is the most rostral, or anterior (closest to the head), see the figure below

Figure 1. Blood supply to the GI tract and anatomy of the colon. Image credit: GrepMed.com

- The celiac artery supplies the pancreas, the stomach, the first part of the duodenum, and the liver and the gallbladder

{end of show notes preview}

Michael Gershon, M.D.

Michael Gershon, M.D. is a Professor of Pathology and Cell Biology at Columbia University. He earned his medical degree from Cornell University, followed by a postdoctoral fellowship at Oxford. He has been called the “father of neurogastroenterology” because of his seminal work on neuronal control of gastrointestinal (GI) behavior and development of the enteric nervous system (ENS) and his efforts to raise awareness of the unique ability of the ENS to regulate GI activity in the absence of input from the brain and spinal cord. To this end, he authored the book, The Second Brain, which has become a trade classic. Dr. Gershon has published almost 400 peer-reviewed papers. He has made major research contributions expanding our understanding of disorders of GI motility, irritable bowel syndrome, the role of serotonin as a GI neurotransmitter, and the ability of gut intrinsic sensory nerve cells to trigger propulsive motor activity. Gershon discovered that the serotonin transporter (SERT) is expressed by enterocytes (cells that line the lumen of the gut) as well as by enteric neurons and is critical in the termination of serotonin-mediated effects. has identified roles in GI physiology that specific subtypes of serotonin receptor play and he has provided evidence that serotonin is not only a neurotransmitter and a paracrine factor that initiates motile and secretory reflexes, but also as a hormone that affects bone resorption and inflammation. He has called serotonin “a sword and shield of the bowel” because it is simultaneously proinflammatory and neuroprotective. Mucosal serotonin triggers inflammatory responses that oppose microbial invasion, while neuronal serotonin protects the ENS from the damage that inflammation would otherwise cause. Neuron-derived serotonin also mobilizes precursor cells, which are present in the adult gut, to initiate the genesis of new neurons, an adult function that reflects a similar essential activity of early-born serotonergic neurons in late fetal and early neonatal life to promote development of late-born sets of enteric neurons. Dr. Gershon has made many additional contributions to ENS development, including the identification of necessary guidance molecules, adhesion proteins, growth and transcription factors; his observations suggest that defects that occur late in ENS development lead to subtle changes in GI physiology that may contribute to the pathogenesis of functional bowel disorders. More recently, Drs. Michael and Anne Gershon have demonstrated that varicella zoster virus (VZV) infects, becomes latent, and reactivates in enteric neurons, including those of humans. They have demonstrated that “enteric zoster (shingles)” occurs and may thus be an unexpected cause of a variety of gastrointestinal disorders, the pathogenesis of which is currently unknown. [Columbia University Irving Medical Center]

Do the pill forms of probiotics “work”? For example, TruNature has a pill form that people rave about. I eat Bulgarian yogurt but maybe supplementing with a pill form wouldn’t be a bad idea. If it actually did something good.

It seems that the great Attia podcasts consistently create more questions than answers. It should go without saying that — Dr. Gershon has truly earned the “father of field” title, given his multi-decade career focused on advancing the collective knowledge of what affects human health. Truly remarkable. But the pace of progress from my vantage point feels so slow.

Even though I remain tremendously skeptical about “functional” medicine, I suspect the next generation of breakthroughs are going to come from there. The connection of metabolic dysfunction and intestinal permeability with inflammation and auto-immunity seem to be the dominant theme driving almost all disease. I posit that the future will be mostly composed of “[reverse] translational science and medicine.” I suspect the advances will come from reverse-engineering the mechanism of action from observation of what is working on the front-lines.

Nice review. However, an opportunity to bring up the important features of Prions and similar molecules would have been informative.

Particles must be less than 1mm to pass the pyloric valve? Anyone who has eaten corn knows this isn’t correct.

Zing. And what causes a diverticula? Lack of fiber? Distal fructose? Can corn cause diverticulitis?

It was stated that larger items (dime, pins, etc) do pass, usually during the cleaning cycle at night. Search this page for the term “dime”.

Another topic to consider would be the role of the Vagus nerve on modification of various diseases.

Take a look at the work of Dr. Kevin Tracey @ the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4533843/pdf/nihms488471.pdf

Fantastic episode from a pioneer in the field; his book was really the definitive work on the enteric nervous system for so long, and reinvigorated the field. Would love an AMA on this that would cover some of the newer studies on fermented foods vs. food with fiber, e.g. https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(21)00754-6. There’s also been a lot of discussion recently about the impact of extended water fasts and potential depletion of the gut microbiome, and about time-restricted feeding and the gut microbiome. Would love to hear these addressed when time allows. Thanks again!

Great content and scope, really enjoyed the chat. Never imagined this conversation would cross paths with things like ASD and shingles, but I liked it.

A bit disappointed there was no discussion of fermented probiotics you hear about in the layman world of personal health hacks; Kombucha, Kefir, Kimchi, sourkraut, natto (besides the one thumb up for Activia).