In April I was part of a panel at the Milken Global Conference, the title of which was something like, “Keys to a healthier and more prosperous society.” The panel was moderated by Michael Milken, and it was great to meet him and his rock-star staff (especially Shawn Simmons, Paul Irving, and Nancy Ozeas). The other panel members were seasoned vets of the obesity discussion: Troy Brennan (Executive VP and Chief Medical Officer of CVS Caremark), Tom Frieden (Director of the CDC), Lynn Goldman (Dean of the School of Public Health at the Milken School of Public Health, at George Washington University), and Dean Ornish (president and founder of the Preventive Medicine Research Institute). I was the pauper in the group—no big credentials and zip-zero “panel” experience.

A few weeks before panel, we all jumped on a conference call and Michael set the stage for the discussion he wanted to moderate. He pulled no punches. “If you include the indirect cost—lost productivity, for example—the total cost of obesity and its related diseases is $1 trillion per year to our economy. This is unacceptable.”

Who could disagree? Hell, I usually only reference the direct cost of obesity and its related diseases—about $400 billion annually. But whether we talk about the direct or indirect cost of these diseases, I’ve always found the human cost even greater—every day 4,000 Americans die from four diseases exacerbated by obesity and type 2 diabetes: heart disease, stroke, cancer, and Alzheimer’s disease. Now that is really un-effing-acceptable.

So, back to the panel. The idea of being on a panel kind of freaked me out, even more than the sheer terror and vulnerability of TEDMed. No control. The possible need to be defensive. Sound bites over substance.

I don’t enjoy debates. Nothing comes of them. Just greater and greater polarization. The “winner” isn’t even necessarily the one with the best “facts.” Gary Taubes shared this quote with me recently, which I find really insightful. Dallas Willard, a well-known ecumenical pastor and theologian, was often invited to debate the existence of God and other matters. These invitations included Richard Dawkins himself. His response: “I don’t debate, but I am glad to enter into a joint inquiry. We will seek the truth together.” That’s the attitude I like.

In the end, I decided to just tell a few (in some cases provocative) stories. Why? Because it’s easy to present reams of data, yet so few people remember the point. (If you want to read an amazing paper on the importance of storytelling, check out this one by one of my former surgical mentors, Curt Tribble. You don’t need to care one iota about training cardiac surgeons to realize the gems in this piece.)

I realized going into this that I would be the contrarian in the group. I don’t claim to know all (or even many) of the answers, but I’m willing to bend over backwards in search of them. I realize folks (from readers of blogs to members of the audience at the Milken Global Conference) want facts, answers, prescriptions. I think we need to know more, first.

Below are the notes I made for myself in the days leading up to the panel. Basically, I wanted to tell a few stories, plus summarize it all (if given the chance). I didn’t actually “practice” this or even take notes up on stage (which I regretted when I realized everyone else was smart enough to bring notes), so if you decide to watch the actual video of the panel, you’ll note that I only vaguely followed what’s written below.

But in my mind, here’s how I thought about it. (I haven’t watched the video and I’ve pretty much forgotten anything I said, but I’m sure what’s written below is better than anything I said. I did send the video to two of the best speakers I know to get their feedback. Their feedback: could have been much better, but not the worst job ever. Lots of work to do for next time. Duly noted.)

How did I find myself interested in this problem?

My arrival at this place is really a coming together of two revelations. First, during my surgical residency at Johns Hopkins, not surprisingly, I was often dealing with the complications from diabetes and obesity in my patients. It slowly became obvious that all I was doing was slapping on the surgical equivalent of Band-Aids without ever addressing the underlying problem. I was treating symptoms and not the actual disease. When I would amputate the leg of a diabetic patient, which I had to do, regrettably, all too often, I knew that my patient was more than likely to be dead within five years anyway.

The second revelation was five years ago—September 8, 2009—to be exact. I remember it so clearly. My sport of choice was marathon swimming, and I followed what I believed to be the iconic healthy athlete’s diet. I had just completed an especially difficult swim into the current from Los Angeles to Catalina Island, becoming one of a dozen people to do that swim in both directions. After more than 14 hours in the water, I got on the boat to begin the long ride back to Long Beach Harbor, and my wife looked at me, in my speedo, 40 pounds heavier than I am today, and said, “Honey, you’re a wonderful swimmer. But you need to work on being a bit less not thin.”

And not only was I, well, fat, despite all this maniacal exercise, but it turns out I was also pre-diabetic.

Her comment launched me into a series of nutritional self-experiments. I was already working out three to four hours a day, so the problem couldn’t be sedentary behavior. It had to be what I ate. Over the next year I manipulated my diet until I found what worked for me, which paradoxically didn’t involve eating less, just eating very different from the food pyramid. Along the way I became obsessed with reading the nutrition literature. What I learned was that the evidence supporting our dietary guidelines was ambiguous, at best, and occasionally contradictory. There was a real dearth of evidence to support what seemed like the obvious questions.

I realized then, that if the guidelines didn’t work for me and if I can’t figure this out, with my background as a doctor and someone who studies healthcare, maybe they don’t work for a lot of people. Maybe there are systemic problems here. Maybe these problems were at the root of the ongoing epidemics of obesity and diabetes. Lots of maybes…and not a whole lot of clear, solid, unequivocal answers.

Since then, I’ve made a personal and professional commitment to finding the answers. And if the studies don’t exist to give us unambiguous evidence, then raising the funds and enlisting the researchers necessary to do those studies.

What does success in public health look like?

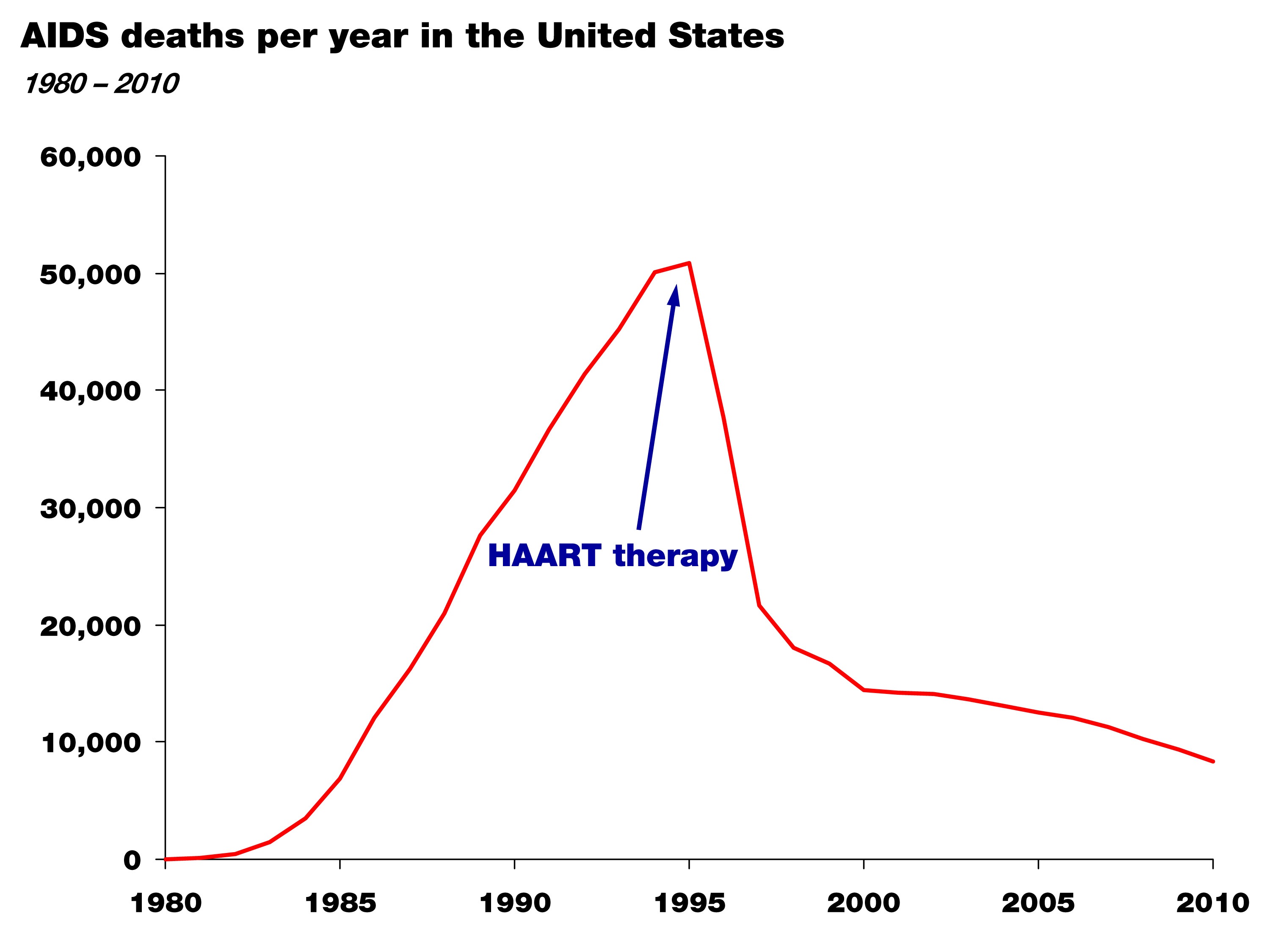

When trying to understand complex problems, I like to start with success stories, identify patterns and work backwards—reverse engineering success. Consider the following graph.

It shows the death rate from AIDS in the United States between 1981 and 2010. The point of this graph isn’t subtle. Death from AIDS rose steadily and monotonically through the mid-90s and since then has declined steadily. Though people still die from AIDS, this still represents a success story in health policy and science. For those experiencing the personal tragedy of AIDS, this is salvation.

So why did it happen? Well, first, the cause of the disease was correctly identified—the HIV virus—in the mid-80s; and second, by the mid-90s highly active anti-retroviral therapy, or HAART therapy, was able to effectively treat the virus and prevent progression to AIDS.

Again, two things happened: the cause of the disease was correctly identified, and an effective treatment was developed by an enlightened healthcare profession.

This is what success looks like. Now, let’s compare this story to that of obesity and diabetes.

Do we have this situation under control? The case study of “failure”

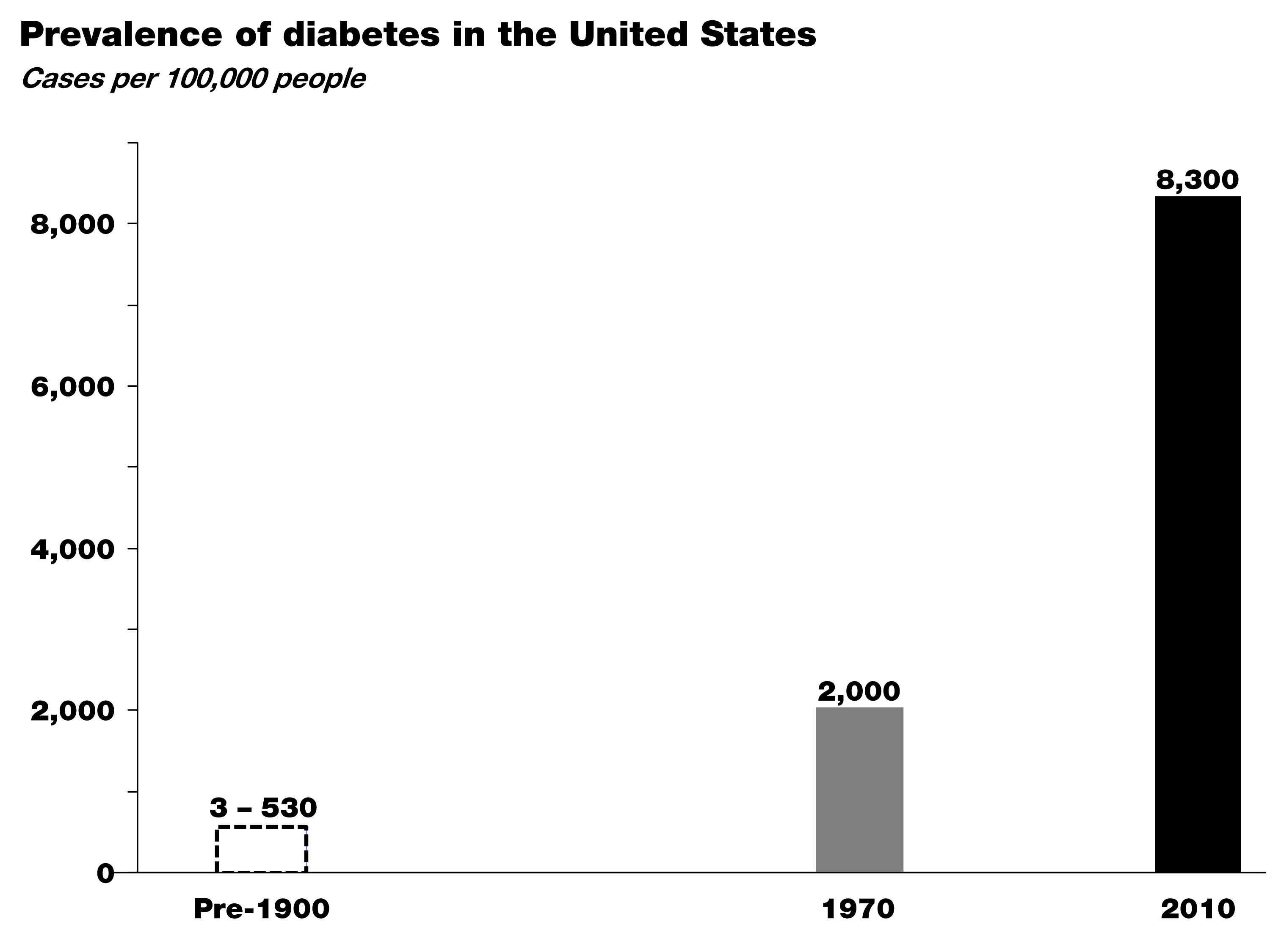

Let’s take a look at this figure. It shows the prevalence of diabetes in the United States over the last hundred-plus years. (Thanks to Gary Taubes who dug up these stats while researching his upcoming book.)

In the early 1900s the leading figures in medicine, Sir William Osler at Johns Hopkins and Elliot Joslin at Mass General, did exhaustive analyses of the number of patients with diabetes based on hospital records and census data. As you can see, diabetes was exceedingly rare in the 19th century—somewhere between about 3 and 500 cases per 100,000, depending on the analysis.

By 1970, around the time I was born, that number was up to 2,000 cases per 100,000, and between 1970 and today—at a growth rate of nearly 4% per year—that number has risen to more than 8,000 cases of diabetes per 100,000.

Worse yet, type 2 diabetes is now spreading into demographics previously naïve to the disease, particularly children. I don’t think any of us in this room today would argue that we have this situation under control. So where are we failing? Many of you understand the world of business. If this were a business, we’d be asking a lot of questions at this point, or we would be out of business. Like any business, we have two possibilities. We either look at our business plan (the basic premise for how we’re going to succeed) or the implementation of that plan (the way we operate on a day-to-day basis). When confronted with a runaway epidemic like this, we have to address the same two basic issues:

Either we understand the underlying cause of this disease and we have a good plan in place, but few individuals have the willpower or wherewithal to avoid the disease—whatever it is…In other words we’re not executing the plan.

Or, we don’t understand the disease in the first place and we’re giving the wrong advice. In other words, we don’t have the right business plan.

In this latter scenario, the failure is not one of personal responsibility, but of our assumptions about the cause of this disease. And these two scenarios have very different implications.

I am not certain which of these is more likely correct, but I do know the risk of ignoring the latter in favor of the former is not a choice we can make any more as a society.

So, maybe the question we should be asking is whether we are right about the environmental triggers of this disease—the underlying cause. Is it as simple as gluttony and sloth and a food industry that overwhelms us with highly-palatable, energy-dense foods, or is there something specific about the quality of the food we’re consuming that triggers these disorders? If we don’t answer this question about what is it in our environment that’s causing this disease correctly, just like we were able to answer it in the mid-80s with HIV’s role in AIDS, we can’t effectively treat the disease. Instead we’re stuck putting on Band-Aids.

Here’s another way to think about it: imagine this panel was on a new crisis in aviation. Planes are constantly crashing—falling out of the sky—and killing 4,000 people a day (just like obesity-related diseases are killing 4,000 Americans a day.) And you’re a pilot and you tell me that surely we understand the principles of flight. Right. Sure, we might suspect user error to be part of the problem. (Maybe the pilots aren’t flapping the wings hard enough!) But, maybe a better idea would be to go back to the drawing board to make sure we really understood this whole aerodynamics thing and we didn’t miss something important?

That’s how we think we have to look at this problem: 4,000 people in this country are effectively falling out of the sky every single day—dying—and we’re saying we’ve got it all figured out, and people just need to adhere better to our advice. I’m not confident that that’s the solution. Nor should you be.

Is there a policy-based solution to this problem?

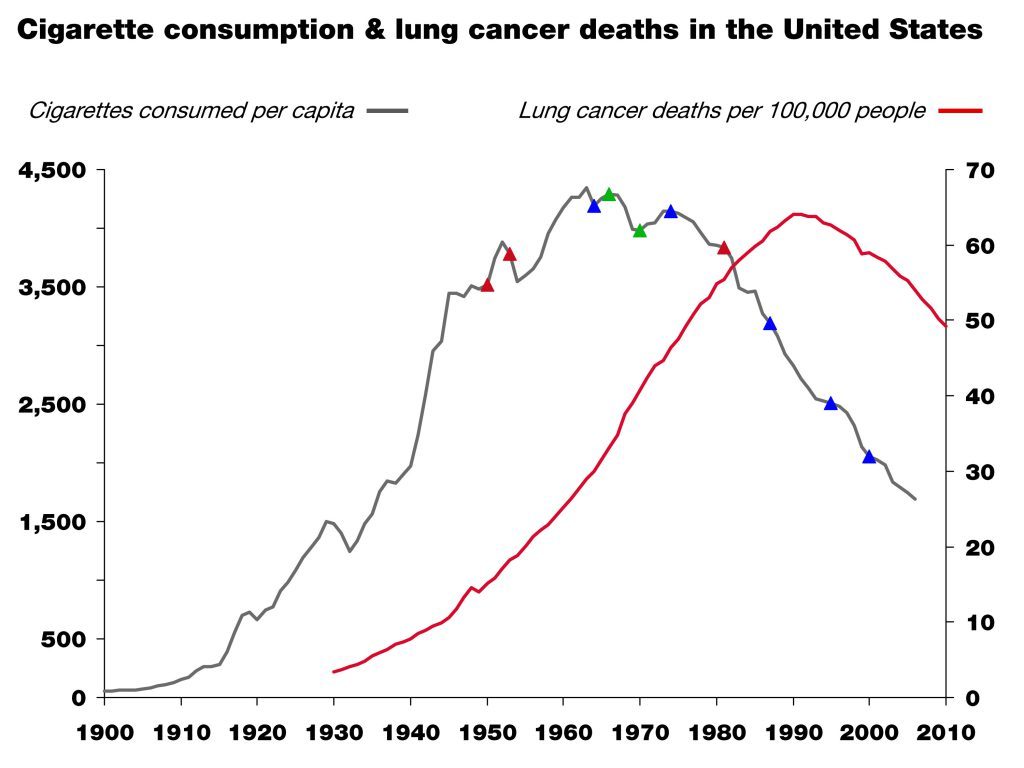

Surely policy changes will play a necessary role in restoring our health. But it may be less about ‘how?’ and more about ‘when?’ I’d like to refer to this slide showing per capita cigarette consumption in the U.S. from 1900 until today—the number of cigarettes consumed is shown in grey with death rate from lung cancer superimposed in red.

This is another success story. People in this room contributed to that success. The little colored triangles on the grey line are major milestones in science (red), market forces (green), and policy (blue). This is a great example of what one might call the “critical confluence”—scientific elucidation, policy action, market response, and behavioral shift—all coming together to save lives.

But, as in all things in life, algebra included, the order of events matters!

Which came first then? In the case of smoking and lung cancer, it was unambiguous scientific clarity, which in this case happened in the 1940s and 50s and resulted in the 1964 Surgeon General’s report. This information was absolutely necessary to drive the policy action, the market response, and the behavioral shift that followed. Without the knowledge that lung cancer is caused by smoking, no amount of policy or market response would have led to the necessary behavioral shift and so a meaningful reduction in lung cancer incidence.

When we consider the current situation with obesity and diabetes, we may still be missing the equivalent of the scientific clarity linking unambiguously the environmental trigger (smoking) that provided the obvious method of prevention (smoking cessation). And, again, if we think we do have that information, we have to ask why we’ve thus far failed to meaningfully prevent and successfully impact these disorders.

If the death rate from AIDS was still skyrocketing, I think we’d all agree we would either call into question our faith in HAART, or even the premise that HIV causes AIDS, if not both. Yet, in the face of skyrocketing obesity and diabetes, we play the who’s-on-first game all day long pointing fingers at people and industry.

Until we clearly identify the dietary triggers of obesity and diabetes, policies to shift behavior may be misguided and premature, despite their best intentions. Despite our best intentions.

I’m arguing that the policies so far may have been just that. Premature. And based on incomplete or faulty information. In other words, we may have the wrong business plan, but we blame our execution of the plan on our failure.

Parting shot

Today, we’re talking about a problem that touches, directly or indirectly, every single person in this room. It’s a topic that can be confusing and at times polarizing. We can’t lose sight of the big picture, which is easy to do when we just look at this problem through the lens of personal responsibility or will power. Remember, I used to think that “If people just learned to eat ‘right,’ (whatever that is), exercise and control themselves and their diet, everyone would be fine.” Today I reject that logic and the hubris that fostered it.

In the business world we know that the wrong strategy, no matter how well implemented, gives us little chance of success. Similarly, the right strategy, if poorly executed, often fails. What we need is the right strategy first and then the right execution second. At the moment, it’s hard to argue that we’re not failing with at least one of these two tasks. The question is which one.

Much of the discussion around this topic focuses on the execution; little attention is paid to the strategy or underlying insights that form the basis of the intervention.

Just 40 years ago the prevalence of obesity in this country was about one-third of what it is today, and that of diabetes about one-fifth. Is this all because Americans have become too gluttonous and slothful and the food industry figured out how to make food cheap and addictive enough? That they simply are too lazy and stubborn to do what we’ve been telling them to do—eat a little less, exercise a little more—for fifty years. Maybe. And I trust many good minds are already working on solutions to address that hypothesis.

However, what if the problem isn’t about non-compliance but about the nature of the advice we’re passing along. Maybe it’s our failure in that we have a simple idea about what causes these diseases, and like many simple ideas—paraphrasing Mencken here—it just happens to be wrong. It’s hard to fathom that two out of three Americans are simply too lazy to be active and too stubborn to eat healthy, despite losing their lives and their loved ones to the negative sequelae of these diseases. I find that hard to believe.

So, what if the problem is that our dietary advice is wrong in the first place? And incorrect dietary advice has resulted in an eating environment where the default for most people is a diet that causes obesity and diabetes?

If HIV or lung cancer were still spiraling out of control—as they were thirty and fifty years ago before the causes were unambiguously identified—the great minds in this country and the world would be leading investigative teams of scientists to figure out what we may have missed in our understanding of the cause of these diseases. We would not be complacent, perhaps because it would be harder to blame these diseases on the victims and their lack of will power. When we fail completely to prevent two devastating disorders for half a century, isn’t it time to investigate what we might have missed—what is it about these disease states that we do not understand? If nothing else, shouldn’t we hedge against the possibility—however slim you think the odds are—that we’re not as smart as we think we are. Those of us who are here today because of our business acumen know the importance of hedges in business. Isn’t it time we did that with obesity and diabetes?

Photo by PICSELI on Unsplash

Great post Peter. I often find myself thinking about the strategy issue in a similar, but slightly different way. For many of societies largest issues, I wonder what portion of resources get spent on treating the symptoms of the problem vs. understanding and treating the root problem. I can’t seem to find a significant societal issue where it feels like we are investing proportionally enough resources into understanding root causes. Which leads me to wonder if this is *the* root problem.

Maybe for every societal issue we face (health, financial system risk, climate change, etc.) we would be best off fixating on trying to get a meaningful proportion of resources devoted to investigating the root cause of the problem vs. constantly trying to simply treat the symptoms of the problem.

Thanks, Mark. I agree, sadly, with your observation. I do think we’d be better off, at least for the persistent problems, going after the root vs. just the symptoms. If we only fixated on giving tylenol to lower fevers without ever thinking maybe the fever was caused by a bacteria, well, you know…

Well people don’t go to doctors much. Forgive the cynicism, but if patients make themselves well without help from their doctors, or if the doctor knows why the patient has symptoms of type 2 diabetes and has a cooperative patient who gets well on the doctor’s program, the annual earnings of the doctor is going to go down.

If doctors know patients have type 2 diabetes but never mention the word, they have a chance to increase their annual earnings.

It took me 40 years (in the Chicago area!) to find a doctor who knows and cares enough to confirm my plan for recovery. Now in my fourth year of recovery and still see that doc, usually only once a year. Thank heaven for the ones who know and actually help; they’re rare.

What an amazing post. So thoughtful and reasonable without the decisive rhetoric that taints so much of this debate. It reminds me of how elon musk describes innovation: you must utilize ‘first principal thinking.’ Break it down to its most basic, fundamental parts and question each one. Could this be improved? Is this here just because our predecessors chose it?

Thanks, Larry. Flattering comparison!

Wow blast from the past but I’m reminded that Milken himself wrote a diet or cookbook around 1999 – 2000, rebounding from his colon cancer (I think) pretty much promoting all-soy-all-the-time. Soy bacon, soy shakes, tofu this and that. Wow I really really wish I’d never been exposed to that book!

Yes, and now beware the madness of crowds… especially when there’s marketing and money at stake.

Average daily energy expenditure from physical activity in the US over the last half century has declined by 100 calories.

At the same time, average daily per capita calorie consumption is up by 200 to 500 calories over the last 40 years. It think the lower end of the range is probably more accurate.

If those numbers are true, they could certainly contribute to the prevalence of T2 diabetes and obesity. Willpower and discipline may play a role in reversal.

-Steve

References:

Church, T., Thomas, D., Tudor-Locke, C., Katzmarzyk, P., Earnest, C., Rodarte, R., Martin, C., Blair, S., & Bouchard, C. (2011). Trends over 5 Decades in U.S. Occupation-Related Physical Activity and Their Associations with Obesity PLoS ONE, 6 (5) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019657

Swinburn, B., et al. Increased food energy supply is more than sufficient to explain the U.S. epidemic of obesity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2009 (90): 1,453-1,456.

These numbers don’t tell the story. When you look at error bars on them, it becomes clear we have little idea how much more or less we eat today than 40 years ago. Data are based on food availability and, at best, sometimes include waste. The expenditure data may be even less reliable. But given that we are indeed more overweight today than 40 years ago, it’s a given that (on average) people consume more than they expend relative the past. That’s merely a descriptive modifier. What’s missing is the explanation one. If I told you Bill Gates was rich because he “made more money than he spent” would that be saying another beyond the obvious? It’s true, sure, but it doesn’t say why. That’s what we should be asking ourselves.

Blaming the patients: “Average daily energy expenditure from physical activity in the US over the last half century has declined by 100 calories. At the same time, average daily per capita calorie consumption is up by 200 to 500 calories over the last 40 years. It think the lower end of the range is probably more accurate. ‘

Read Taubes: Good Calories, Bad Calories

https://drhyman.com/blog/2011/08/04/new-research-finds-diabetes-can-be-reversed/#close

New Research Finds Diabetes Can Be Reversed

by Mark Hyman, MD

I have recently spent more time in drugs stores than I would like helping my sister on her journey through (and hopefully to the other side of) cancer. Rite Aid, CVS and Walgreens all had large diabetes sections offering support for a “diabetes lifestyle”—glucose monitors, lancets, blood pressure cuffs, medications, supplements and pharmacy magazines heavily supported by pharmaceutical advertising. Patients are encouraged to get their eye check ups, monitor their blood pressure, track their blood sugars, have foot exams and see their doctor’s regularly for better management of their blood sugars—all apparently sensible advice for diabetics.

But what if type 2 diabetes could be completely reversed? What if it wasn’t, as we believe, an inexorable, progressive disease that has to be better “managed” by our health care system with better drugs, surgery and coordination of care? What if intensive lifestyle and dietary changes could completely reverse diabetes?

A ground breaking new study in Diabetologia proved that, indeed, type 2 diabetes can be reversed through diet changes, and, the study showed, this can happen quickly: in 1 to 8 weeks. That turns our perspective on diabetes upside down. Diabetes is not a one-way street.

If we have a known cure, a proven way to reverse this disease, shouldn’t we be focused on implementing programs to scale this cure?

We used to believe that once cells in your pancreas that make insulin (beta cells) poop out there was no reviving them and your only hope was more medication or insulin. We now know that is not so.

Continuing misconceptions about what causes diabetes and our unwillingness to embrace methods know to reverse it have lead to a catastrophic increase in the illness. Today one in four Americans over 60 years old has type 2 diabetes. By 2020, one in two Americans will have pre-diabetes or diabetes. Tragically, physicians will miss the diagnosis for ninety percent with pre-diabetes or diabetes. (Below I tell you exactly what tests to ask your doctor to perform and how to interpret them).

From 1983 to 2008, world-wide diabetes incidence has increased 7 fold from 35 to 240 million. Remarkably, in just the last 3 years from 2008 to 2011, we have added another 110 million to the diabetes roll call. And increasingly small children as young as eight are being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (formerly called adult onset diabetes). They are having strokes at 15 years old and needing cardiac bypasses at 25 year old. The economic burden of caring for these people with pre-diabetes and diabetes will be $3.5 trillion over 10 years.

If we have a known cure, a proven way to reverse this disease, shouldn’t we be focused on implementing programs to scale this cure? Unfortunately despite this extraordinary new research, the findings will likely be pushed aside in favor of the latest greatest pill or surgical technique because behavior and lifestyle change is “hard.” In fact, with the right conditions and support, lifestyle diet and lifestyle change is very achievable.

What did research show?

Reversing Diabetes: Can it Be Done in a Week?

The study, entitled Reversal of type 2 diabetes: normalization of beta cell function in association with decrease pancreas and liver triglycerides, was exquisitely done. The bottom line: A dramatic diet change (protein shake, low glycemic load, plant-based low-calorie diet but no exercise) in diabetics reversed most features of diabetes within one week and all features by eight weeks. That’s right, diabetes was reversed in one week. That’s more powerful than any drug known to modern science.

We know from gastric bypass patients that with rapid changes in diet right after surgery, within just a few days, without significant weight loss, diabetes goes away—fatty livers heal, cholesterol levels plummet. Some theorized it was because of changes in the stomach hormones related to the gastric surgery. Others, including the researchers of this new study surmised that maybe it was just the drastic change in diet. So they went about studying just the diet change without surgery.

They studied 11 people with diabetes and compared them to a control group. Through very sophisticated techniques including MRI imaging, they measured their blood sugar and insulin responses, cholesterol levels and fat in the pancreas and liver (some of the hallmarks of diabetes) before and after diet changes at 1, 4 and 8 weeks.

What they found was revolutionary. The beta cells—the pancreas’ insulin producing cells—woke up, and the fat deposits in the pancreas and liver went away. Blood sugars normalized in just one week, triglycerides dropped in half in one week and reduced 10-fold in eight weeks. The body’s cells became more insulin sensitive and essentially, in just 8 weeks, all evidence of diabetes was gone and the diabetic patients looked just like the normal controls on all the testing.

While this may be surprising to most, it is something I see regularly in my medical practice. With focused, strategic, scientifically based nutritional intervention, combined with exercise, stress management and sugar and insulin balancing nutritional supplements, many of my patients completely reverse their diabetes. And the side effects—more energy, better sleep, improved sexual function and weight loss—are all good.

What most don’t realize is that pre-diabetes and diabetes exist on a continuum and both dramatically increase the risk of heart attacks, stroke, cancer, infertility, sexual dysfunction, depression and dementia. You don’t have to get diabetes to be at risk for all those problems. That is why it is so important to get your doctor to diagnose pre-diabetes early and implement an intensive lifestyle program to help you reserve it.

You may be at risk if you have extra belly fat, have a family history of diabetes, gestational diabetes, are in at risk ethnic group (Asian, Hispanic, African American, Native American, Middle Eastern), have high triglycerides (> 150 mg/dl) or a low HDL (< 50 mg/dl) or have high blood pressure.

If any of these apply to you or you have other cause for concern, here is what to do.

How to Reverse Your Diabetes

First, get your doctor to test the following:

1.A 75-gram glucose tolerance test measuring BOTH glucose and insulin fasting and 1 and 2 hours later. Your fasting blood sugar should be less than 100 mg/dl and your 1 and 2 hour sugar levels should be less than 130 mg/dl. Your fasting insulin should be less than 10, and your 1 and 2 hour levels should be less than 35.

2.Triglycerides should be less than 150 mg/dl and HDL (good cholesterol) should be over 50 mg/dl, and the triglyceride to HDL ratio should be less than 4. These ranges are meaningful only if you are on no medication.

3.Newer cholesterol tests measure the size of your cholesterol particles and is very effective in diagnosing problems with pre-diabetes early. In fact, this is the only cholesterol test we should be performing.

And here’s the program I use for my patients to reverse diabetes:

1.Eat a low glycemic load, high fiber, plant-based diet of vegetables, beans, nuts, limited whole grains, fruit and lean animal protein

2.Vigorous exercise (fast walking, running, biking, etc.) 30 minutes 4-5 times a week and strength training 20 minutes 3 times a week

3.Take a good multivitamin, fish oil, vitamin D and blood sugar and insulin balancing nutrients (including chromium and alpha lipoic acid)

Remember, pre-diabetes and diabetes is not a one way street and the solution is not at the bottom of a pill bottle or the end of an insulin syringe, it is at the end of your fork and in the shoes on your feet!

Now I’d like to hear from you …

Do you think diabetes can be reversed? If so, how?

What methods have you tried to gain control of your diabetes or weight gain? How have those methods worked for you?

Why do you think accessible, scalable, lifestyle solutions like these that actually reverse chronic illness are not more frequently prescribed in conventional doctor’s offices? How can we change this?

Please share your thoughts by leaving a comment below.

To your good health,

Mark Hyman, MD

Social norms have changed which may help explain increased calorie consumption. One example a 4yo birthday party we went to yesterday. 40 years ago a party would have consisted of cake and maybe lunch. Yesterday, pastries, lunch (pizza and pasta), cake, free soda fountain, a giant table laden with sugary junk, a pinata more candy, and “Frozen” cotton candy. Other social norms – daily high calorie coffee consumption, free soda fountain at work, eating out instead of brown bag at work, etc. What is “normal” has changed in my view.

Hazel: For a different perspective on how to reverse diabetes, check out Richard Bernstein’s book “The Diabetes Solution.” Whereas Hyman advocates a plant-based diet, Bernstein recommends a more typical very-low-carb diet. He, too, maintains that type 2 diabetes can be reversed, and that the side effects of type 1 diabetes can be reversed.

Peter, based on the cover and article in current issue of Time, in which you are mentioned, looks like word is finally getting out in the mainstream re fat vs. carbs and some of the dietary issues you, among others, are raising. Must feel good to be part of that.

I think it’s a step in the right direction. But there are 3 mighty pillars of nutritional wisdom that still need to be tested and, if necessary, overturned.

Hi Dr.Attia,

I discussed the failure & successes of treating obesity/T2D with Dr.Guyenet. It seems to have “hit a nerve”, spurring him to write this post “Has Obesity Research Failed?” [https://wholehealthsource.blogspot.fr/2014/06/has-obesity-research-failed.html].

In this post you use AIDS as an example of ‘success’, which I thought was all the more interesting considering Dr.Guyenet specifically says “Obesity is much more challenging than a simple infectious agent or nutritional deficiency that can be readily treated”.

He goes on to say: “I hope it’s clear that obesity research has not failed– it has produced huge amounts of scientifically robust information, and a number of effective therapies. None of these therapies are the magic bullet we wish they were, yet there’s no reason to believe this is because our understanding of obesity is fundamentally flawed.”

Your response would be greatly appreciated & likely enlightening to both readerships. Thanks!

Well, I agree to some extent with Stephan that obesity may be a more complicated problem than polio, AIDS, or smallpox (i.e., infectious diseases). But that is not the point of my post, if you read it *carefully*

The point is obesity research has largely been a failure because the outcome has gotten better, not worse.

If you’re a CEO and your job is to raise money for your company, you can’t say you’ve been great–you have a great pitch, you communicate well, etc.–if you fail to raise money. Even if those things are true, the final yardstick of your performance is against the initial objective.

If there is another objective for obesity and T2D research beyond reducing their prevalence, fine, evaluate the research against that. But for me, that’s all secondary.

Peter: I just (this morning) finished reading “Mistakes Were Made (but Not by Me)” on the recommendation of your previous post. Fresh in my mind is the closing chapter, wherein the authors explore the value of making mistakes (so that we can learn from them), and of Americans’ cultural loathing of making mistakes (which leads to denying them and, often, to making more to cover up the original ones). They quote Edison on his thousands of initial “failed” attempts to create the incandescent light bulb. He famously said, “I have not failed. I successfully discovered 10,000 elements that don’t work.” Without having read Guyenet’s paper or knowing his philosophy, I wonder if that is the perspective he’s adopting: “We haven’t failed; we have produced reams of information, some of which is useful in addressing this problem and some of which we can discard.” (Of course, more is revealed in the last part of Guyenet’s quote: “…yet there’s no reason to believe this is because our understanding of obesity is fundamentally flawed.” Maybe he is indeed clinging to evidence that needs to be discarded.) Failure would be if we stopped now, having erroneously assumed we’d found the solution, or if we kept doggedly pursuing lines of questioning that obviously keep going nowhere. I know that individual researchers and even some significant groups of researchers no doubt are guilty of those very things. But I’m using the collective “we” here in the broadest sense possible. “We” haven’t failed yet as long as there are people who are willing to continue tackling the problem with fresh eyes. They (hopefully) will learn from and build on the mistakes that were made by their predecessors.

Glad you read it. Carol has become a close friend. She’s also become obsessed with nutrition and hopes to publish a 2nd edition which will include a chapter on nutrition. Lots of material to work with, unfortunately.

“I’m arguing that the policies so far may have been just that. Premature. And based on incomplete or faulty information.”–

What it all comes down to, making policies and telling people what to do when you aren’t even sure it’s right.

This week’s Time Magazine cover story about fat/cholesterol being good after all is a great reminder of this – we have people in “our circles” rejoicing at the relenting of a major media influence, but what about their responsibility almost exactly 30 years ago when they outright said it’s not even up for debate – cholesterol and fat are killing us?

Sorry, you don’t get a hall pass because you are now saying what you think is currently the right thing. The data even back when they published that BS was already pretty clear that sat fat/cholesterol weren’t the problem – but even moreso, there evidence that it IS a problem was completely non-existent, yet they were still willing to tell the world something so polarising based on this?

And of course the other classic example is McGovern and his little speech back in ’72 along the lines of “we don’t have the time to wait for evidence, we need to tell people how to be healthy NOW, and we’ve decided that way is by avoiding animal fats and reducing cholesterol”. Well done fellas.

I’m just glad I spent a life willfully ignorant of policy, and never once missed out on a juicy steak covered in butter.

Bravo!

On a semi-related note, you are probably aware of the take-down of Demasi’s Catalyst program by the Aussie ABC channel. I think this program – and the whole clusterfk surrounding it needs to be seen by as many as possible to understand the suppression of sanity we’re up against.

I’ve put together a host of resources about the program (the vids, transcripts, Cliff’s Notes, links to blogs talking about the behind-the-scenes stuff, etc) here:

– https://highsteaks.com/abc-catalyst-heart-of-the-matter-dr-maryanne-demasi/

Cheers.

Bravo; I copied and saved the info.

Cynical but true; if TPTB can keep the info under wraps, they profit.

Does HIV cause AIDS?

Not everyone thinks so.

https://www.duesberg.com/

And some people think the world is flat and that the sun orbits the earth.

Peter I am disappointed you dismissed this comment so out of hand. I do not think the world is flat or that the sun orbits the earth but I have listened to Dr Duesberg and he raises some difficult questions about the HIV/AIDS hypothesis. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pB8g0b-FkW0 With your intellect and medical knowledge I would love to hear your opinion on this.

How do explain the HAART-AIDS interaction?

Hi, Peter.

I also found your answer here unnecessarily blunt and sarcastically.

I can totally see someone saying ‘Peter Attia believes that maybe diabetes causes overweightness through insuline resistance, haha!’ and then quickly replying, totally convinced of the available evidence on the contrary, the same as you replied.

Personally, I believe your hypothesis is right and the AIDS denialists are wrong. But this is only because I read a lot about the arguments and evidence presented from both sides of both AIDS denialists and non-denialists, as well as lipid hypothesis denialists and non-denialists.

My point here is not so much whether AIDS denialists are right or wrong (much probably wrong), but that the way you rejected the comment seemed hasty and irrational, as if just because the claim seemed a bit absurb (and contrary to the popular medical consensus) it didn’t deserve any thought. This is precisely one of the reasons lipid hypothesis and cholesterol skepticism don’t get wider attention: because it goes against decades-long medical consensus, so ‘it’s definitely nonsense’.

I think your rejection is a true negative. But you seem to have arrived at it with a not-so-good process, which if replicated may yield to false negatives in the future.

Part of it may be simply shortage of time: you were in a hurry and you don’t possibly have time to analyze everything everyone sends you. A better response would have been ‘No time to see it, but find very unlikely to be true, because HAART works based on the premise HIV exists.’

Best.

Interesting read, as always.

The link you provided for “The way we talk is the way we teach” is behind a paywall. I would very much like to read it; do you know of anywhere else it might be found?

Hmmm, worked for me easily. Try to google the title of the article, “The way we talk is the way we teach” and “Tribble.” Hope you can find it.

Yes, It’s about $35 to get the article.

Hopefully this is the beginning point where biases are laid off (even if just a little) and folks like you start thinking more scientifically…as you may precisely know than many studies appearing every day in medical journals poorly resemble the scientific method.

Will post the panel on my support group to debate it. Thanks Peter!

Interesting! A good discussion.

In my own practice I do inform the diabetic patients about eating a low carbohydrate diet and a simple walking practice daily. They often reject my help and continue to have elevated blood glucose and non-healing wounds. It is depressing. They won’t even try because they would have to “give up” beer, pizza, etc.

I ‘ve noted the resistance seems to be related to their worsening disease. Can it be a circular problem?

In the clinic we call it Sugar Brain.

Sad, indeed. A complicated answer sits in my head, but it would take another blog post to expand.

It must be immensely frustrating for doctors who know that a simple method of changed eating does work for many people but their patient or patients won’t try. I know many people who won’t, no matter how simple the change may be.

That’s my brother. I have given him the 2011 version of the Diabetes Solution and he hasn’t touched it. I send him articles, posts, studies from scientific journals. But he’s fine. All his numbers are “normal”. Thanks to medication. He won’t “deprive” himself. He came to visit me and had a foot long meatball sub (white bread) and a HUGE serving of french fries. Then gets on the phone to his friend and says he’s doing more cardio now. He still thinks it’s fat that is keeping him fat. He still calls it “grease”. His doctor tells him about 10g of sugar a day is okay. But keep eating that high-carb diet. Thanks to his doctor he thinks he’s doing a great job of controlling it. Our Dad is on dialysis, barely walks, has a pacemaker, is in and out of the hospital and this is at 72 – my Mom has to put his pills in his mouth because he can’t feel his fingers anymore. My brother honestly doesn’t think that will happen to him. My Dad was never obese – he just had the carb belly. My brother is obese. He also has a huge carb belly.

Peter,

I watched the panel discussion and I think your message was quite clear. I’ve talked to so many people who believe that exercise is the answer along with eating a “balanced” diet. I think if people avoided sugar and carbs like they avoided fat, cholesterol and tobacco, we’d see a drop in metabolic syndrome like in those charts you showed above. The problem is, people already have their preconceived notions of what healthy eating already and with all the differences in opinion even in the scientific community, how can there be any effective policy implementation? Like you said, we need to get rid of the noise with hard scientific data that the scientific community, and by extension the policy makers, can come together around.

What are your thoughts about the artery picture, where the top showed an artery of a person that eats whole foods, the middle is a person who eats refined carbs and the bottom is someone who eats low carb high fat diets? I know you’re a supporter of low carb and high fat at least for yourself. Are you worried at all that your arteries are clogging? (My guess is no, but could you talk a bit about it?)

Thanks,

Jack

Jack, you watched the whole thing? Even I don’t have the patience to do that! Most of those pictures are in mice. Also “high fat” diets in mice contain about 20-25% sucrose by weight. So I don’t think we’re learning much. The ones in humans are comparing a low fat AND low sugar/low flour diet to a standard American diet high in fat, sugar, and simple carbs. So, again, no new insight. In short, few people have the insight of what’s going on inside their arteries as much as I do. So for me, at least, I’m not worried.

But I don’t know universally if this is true across the board. Hence my plea for more of the right kind of studies to elucidate this.

I watched it too, the message as outlined in this post got across just fine, the girlfriend picked it up easy enough.

Funniest part was the bit about how the eat less/move more thing is an utter failure, and right on the back of that another speaker tries to reconstruct the house of cards with exactly that approach, how we’re eating 100 calories a day more and exercising less with dramatic pictures of pushbikes dwindling etc.

Ornish has GREAT monologues on how bad the situation is and how to go about fixing it in general that are almost worth a standing ovation – but I just wish he’d stop there. He always stuffs them up by suffixing his personal “hearthealthywholefoodsplantbasedlowfatdiet” dogma to the end of it and somehow constantly slotting in that one time he magically reversed heart disease by getting people off junk food (which is the same as animal protein I guess).

Compelling panel overall, worth a watch to anyone who’s reading this blog.

Dr. Attia,

I am very much interested in your theories as I am one who has developed Type 2 diabetes in the last 7 years. I am 60 years old. I don’t have a lot of information on my heredity, since my mom passed at age 27 with melanoma. However, neither of her parents had diabetes, and neither did any of her siblings. As far as I know, I have one cousin (out of 12) who is 2 years my junior who has developed Type 2 diabetes. I hate this disease! I find my energy down, my depression is up, and I hate constantly trying to figure out what to do to improve my “condition”. I am not looking for an excuse. I am looking for results! I have often thought that the major causes of some of our prevalent diseases was the way our food sources have been “human” contaminated with GMO, pesticides, overuse of land that causes our foods to lack nutrition, and perhaps other things not yet identified.

I cried when I saw your TEDTALK because I had felt the same way before I got diabetes! I think you are definitely on to something!

Elizabeth, the books by Steve Phinney & Jeff Volek, along with that of Richard Bernstein, are great resources.

Elizabeth: I second Dr. Attia’s recommendation of Richard Bernstein’s books. Bernstein says that type 2 diabetes can be reversed with a very low carb diet (and that the complications of type 1 diabetes can be reversed with a VLC diet). Like Dr. Attia and his colleague Gary Taubes, Bernstein is no-nonsense. His only agenda seems to be discovering and disseminating the truth. His personal story as a type 1 diabetic is also intriguing. His website provides a wealth of information: https://www.diabetes-book.com

I came across Bernstein’s work because my husband is a type 1 diabetic, age 51, diagnosed at age 4. He’s in great health, but a few minor complications started to crop up a couple years ago. They improved within about a month of hubby dialing in his blood sugar control a bit more by reducing (not even eliminating) carbs.

Good luck in your journey. I wish you the best. Stay strong!

Elizabeth, I’m 60 and was developing Type 2 Diabetes, according to doc and blood tests and 3.5 years ago started following the diet Gary Taube recommended in his Reader’s Digest article. I lost 40 lbs the first 6 months and have kept it up and have lost 65 lbs. I’m 5’10”. I decided then that it wouldn’t be a “diet” but just a permanent change. I eat pretty all the fatty food I want to, and eventually found myself just eating twice a day because I wasn’t hungrey. The first two weeks are difficult, as the sugar/carb craving comes after you but after that you feel great! I aim for zero carbs, which is nearly impossible, but don’t go any “middle of the road” methods, i.e., only carbs on weekend, only whole grains, etc. Believe nothing that comes from the USDA, FDA, etc. Meat, (of all kinds. Enjoy the fatty cuts), nuts, cheese, whole yogurt, berries (not other fruits), whole cream and milk, peanut butter, green vegetables, other kinds of greens, any kind of fatty dressing, but always check carb content on prepared foods. Absolutely no sugar in any drinks. Believe me it works! Never been so pleased! When you lose the first 5 lbs., it’s so encouraging you just want to keep doing it!

Thank you for another excellent article. I find that the ‘calories in/calories out’ model is firmly ingrained in the psyche of most who have ever tried to lose weight or studied weight management. It takes a lot of effort to relearn what is actually the truth and that is hormones rule.

Bravo! Hail to glucagon.

“The ‘winner’ isn’t even necessarily the one with the best ‘facts.’…I realized going into this that I would be the contrarian in the group.”

It hardly ever happens that debates change anyone’s mind, and they’re more of an intellectual p**sing match than anything else. It takes a lot to overcome the “conventional wisdom” about what food is healthy versus unhealthy, and to undo the paradigm that is so locked in and reinforced via government and corporate interests.

6 months ago, someone could have shown me the dozens of scientific studies showing better weight loss results from low carb diets, or they could have described the problem of insulin and its role in fat accumulation, or they could have shown me all the statistics that demonstrate our current paradigm isn’t working, and my response would have been some dimwitted logical round-robin that would have exposed my ignorance and cognitive dissonance.

I think (some percentage of) people entertain alternative hypotheses when it becomes impossible to ignore the faultiness of the conventional hypothesis. I believe most people are ignorant of this dichotomy, and that’s half the problem.

If you don’t mind me asking, what changed (for you, personally) in the past 6 months?

In my case, it was sort of a “brute force” process of overcoming my ignorance

I’ve always had a tough time maintaining weight. And I have a family history of pretty major heart problems, diabetes 2, cancer, etc. Like most people, I’ve always thought that if I just had more will power, more inclination to exercise, and a willingness to eat fruits, veggies, and “heart healthy grains”, I would have good health outcomes. After all, weight change = calories in – calories out.

Year after year, I would start an diet/exercise program, get discouraged (and hungry), and give up. Then I’d feel bad about myself, consider my fate if I didn’t do something, and the cycle would repeat.

My real catalyst was a little silly and anticlimatic…after eating a 850 calorie piece of red velvet cake, I asked the question: will my body “use” all those calories? In other words, was I going to have to do 120 minutes of cardio to “burn” those calories that took me all of 120 *seconds* to eat?

The question got me started on an exhaustive journey to better understand cellular metabolism, and each question I answered left me wanting to know more about it – adipocytes and skeletal muscles, insulin, HSL and LPL, etc. I was quite ignorant about all of it.

Google led me to your site, and its treasure trove of information. It’s really been a great tool in helping me to understand the science of it all. So, thanks for that!

Very interesting journey. Appreciate you sharing it, Tim.

Although your question was posed to Tim and not to me, I can tell you what changed MY mind two years ago. I hold a BS (ha!) degree in nutrition, from 1984 (but I never completed the additional training to become an RD). I edit health-oriented self-help books for a living. So I’ve been a student–formally and informally–of nutrition, health, and fitness for 35 years. Like Tim, I was committed to the calories in/calories out theory (aka the “gluttony/sloth” hypothesis). As someone who has never had a weight problem, and who can eat a LOT without gaining much weight, but who has always eaten a fairly “healthy” diet (never indulged in much junk food and cooked mostly from scratch), I sort of wondered, “What’s so hard about this?” I also am a fitness instructor (Jazzercise) and teach 4-5 classes per week. I haven’t read popular diet books obsessively, but I have read a few, and of course have stayed aware of the most popular diets (via cultural exposure, with a bias on my part toward absorbing nutritional info) and could summarize most of them more or less.

About two years ago I heard a 10-minute radio interview with Gary Taubes. I was like, “Great…another ‘expert’ who thinks he’s discovered the magic bullet. And he’s not even a doctor.” But something about his measured tone and his logic caught my attention. Still, I was resistant to having my paradigm challenged.

Shortly thereafter, a vegan friend of mine posted on FB a link to an article by John McDougall, whose book “The Starch Solution” was just coming out. I looked at the article. It was compelling in certain ways, but mostly I found McDougall’s argument based as much on rhetoric as on facts. Remembering the interview with Taubes, I felt some cognitive dissonance, but wrote it off to “There are so many conflicting theories out there. What are you gonna do? I guess I’m one of the lucky ones.” (I still think I more or less lucked into my metabolism.) Then I was shopping at my regular grocery store, walking down the “popular books” aisle (which I never really pay much attention to) and noticed GT’s “Why We Get Fat” at eye level. I thought, “What the heck?” So I bought it. And I immediately went home and ordered McDougall’s “Starch Solution.” I read the two in quick succession. It was Gary’s obvious commitment to finding the truth that won me over. His tone (“I think I’m on to something, but lots more research needs to be done” rather than “I’ve discovered The Truth and now I just need to convince you”–ie, McDougall’s tone) was just right.

It’s not precisely accurate to say that I’ve become a staunch devotee of the low-carb philosophy (although I find that if I minimize carbs in my diet, I don’t have to think about my weight at all). Mostly, I’ve returned to my questioning ways. So, thanks GT and PA and NuSI. This journey of exploration has been among a handful of life-changing ones for me.

Correction: On re-reading Tim’s comment, I see that he didn’t specifically talk about hewing to the “calories in/calories out” theory. Yet in my comment I mentioned his doing so. My mistake. Sorry, Tim.

I have not had a chance to see the video. Before approaching a “problem”, you have to have the “right” people, with the “right” mentality.

Keep up the great work!

Even Luc Montagnier, directly says HIV infection alone is “not enough” to cause AIDS. If you find a scientific paper that proves that HIV causes AIDS let Kary Mullis know. He’s been looking for it for 20 years! Haha!

So what’s your answer? Kary Mullis is definitely a smart guy, but if that’s your benchmark for truth you should get familiar with his other positions rather than just say, “he’s been looking at it for 20 years.” That means nothing.

Thanks for all you are doing to change the world. Sounds hyperbolic, but it’s true.

When is Gary’s book coming out?

I don’t know (and I don’t think he knows either!).

Good post Peter.

Trouble is, when you have doctors like Ornish, Essylstein, McDougall, etc. spewing forth their unscientific BS, it’s a tough road ahead. These people are not interested in the science behind the issues, they are only interested in their own agenda.

When these people are taken seriously as Ornish always is, so too are their ideas and this is unfortunate. In our efforts to seem fair, reasonable and accepting of other viewpoints – viewpoints that are absolutely wrong – we shoot ourselves in the foot. Ornish shouldn’t even be on that stage.