I embarked on a self-experiment last weekend to see if I could better understand the interplay between the different types of exercise I do and ketone production (beta-hydroxybutyrate, or B-OHB, to be specific). To be clear, nothing I do with a sample size of one “proves” anything, but sometimes self-experiments can help you formulate hypotheses and, if nothing else, understand how your body works. Consider the parable of the black sheep. If you see even a single black sheep in the field, depending on your field of training, you can draw conclusions:

Three scientists were on a train and had just crossed the border into Scotland. A black sheep was grazing on a hillside. The biologist peered out of the window and said, “Look! Scottish sheep are black!” The chemist said, “No, no. Some Scottish sheep are black.” The physicist, with an irritated tone in his voice, said, “My friends, there is at least one field, containing at least one sheep, of which at least one side is black some of the time.”

My point is, even a self-experiment of one can be good for something.

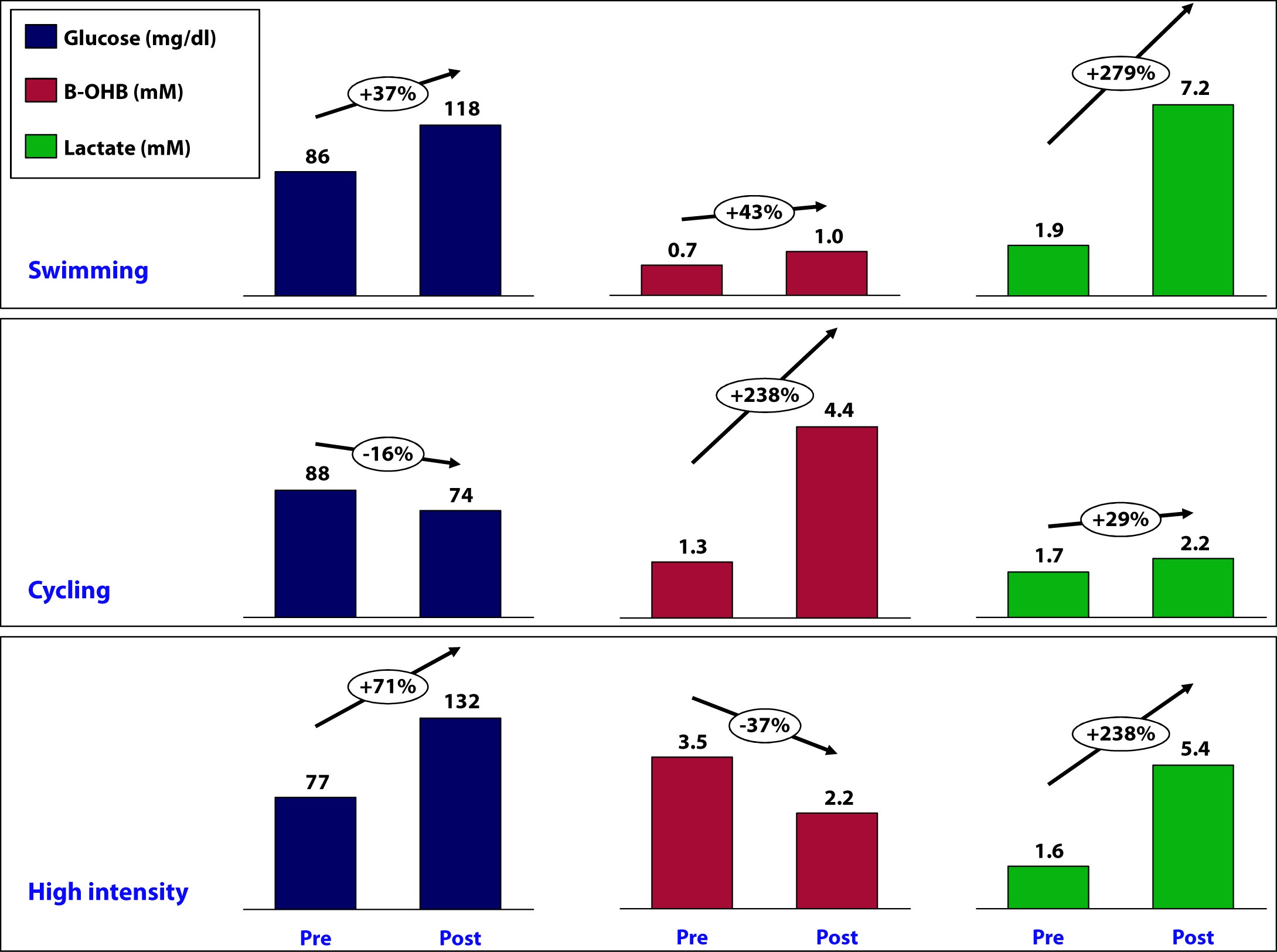

To test the relationship between exercise and ketosis I decided to examine my blood levels of glucose, B-OHB, and lactate immediately before and after three different types of workouts on three successive days. This interplay is complex and no one knows “everything” about it, including the world’s experts (which I am not pretending to be). I’m going to try to balance a fine line in this post – I want to be rigorous enough to explore the ideas with substance but not too detailed to put you to sleep. I hope I am able to balance these forces adequately.

If any of you are not familiar with the work of Jeff Volek and Steve Phinney, but you are interested in the biochemistry of nutritional ketosis, I recommend getting familiar with their work. The list of people who know more about nutritional ketosis is short.

Let’s take a look at the three parameters I measured in a bit more detail. To give you a sense of what is “normal” here are some guidelines:

Glucose

A normal fasting glucose is generally considered to be between 75 and 100 mg/dL. My mean over the past year has been about 90, but I need to mention two very important caveats:

- On the four occasions I have calibrated my hand-held device with an actual laboratory test, my device seems to run high by about 11 mg/dL, so a measurement of 95 mg/dL on my device is probably closer to 84 mg/dL in reality.

- I carry a genetic trait for a disease called beta-thalassemia. The clinical manifestation of this is that I have much smaller red blood cells than normal (about 65% of normal size). There is some evidence in the literature that this condition prevents some accurate testing of any assay that can interfere with hemoglobin. For example, a test measuring glycosylated hemoglobin suggests I have much more glucose in my blood than is actually measured. In fact, the Glycomark test for mean post-meal glucose level suggested I have an average post-meal glucose level of 190 mg/dL which is obviously not true. In other words, something about my beta-thalassemia seems to interfere with, at the very least, measuring glucose linked to hemoglobin, and possibly measuring glucose in general.

I mention these 2 features to say my glucose levels (unlike B-OHB and lactate which I’ve documented to be very accurate) may be artificially elevated. Here’s the important part, though: the discrepancy seems to be constant, so the increases or decreases seem to be good measurements.

Beta-Hydroxybutyrate (B-OHB)

A normal fasting B-OHB level for a “normal” (i.e., non-ketotic) person is zero. Within a day of fasting, you might expect this number to reach 0.2 to 0.4 mM, and about 1.0 mM within 48 to 72 hours of complete fasting, though this is highly variable among subjects.

If you’ll recall from my discussion of keto-adaptation, the threshold for nutritional ketosis is about 0.5 mM. My normal morning fasting level of B-OHB is usually between 1.0 and 2.0 mM with an arithmetic mean of about 1.4 mM.

Both insulin and glucose (probably by causing the secretion of insulin) suppress ketones. This is why, for example, consuming more than about 50 gm of carbohydrates per day and/or more than about 120-150 gm of protein per day makes it difficult to be in nutritional ketosis – too much insulin secretion.

Lactate

Lactate (or lactic acid) is a byproduct of anaerobic exercise. A normal level is considered to be below 2.2 mM. Basically (I’m oversimplifying a bit), when you exercise in a predominately aerobic capacity, while you do generate lactate your liver is able to match muscle production with clearance via a process called the Cori Cycle (a process in which the liver turns lactate back into glucose).

If you’ve ever done a very intense exercise – like run an all-out mile – and felt like your body is completely seizing up and you are unable to move, you’ve experienced a high lactate. Technically, the lactate is not causing this. Lactate gets a pretty bad rap, and it’s actually a good thing as it allows us to generate energy even when we demand it in an environment where sufficient cellular oxygen is absent. The real “bad guy” is the hydrogen ion that accompanies lactate and interferes with the ability of our muscles to contract and relax properly. However, we use lactate as a proxy for the hydrogen that is actually causing the pain and difficulty in muscle contraction.

For me (personally, though this is probably true for most people) the highest lactate I generate tends to be in all-out activities lasting about 2 minutes which use all muscles in my body (the more muscles you use, the more lactate you generate). Hence, the 200 individual medley (IM) race generates the most lactate in my body: It’s 2-plus minutes of maximum exertion sending pain into every muscle in my body (this event requires a swim, in order, of 50 yards each of all-out butterfly, then backstroke, then breaststroke, then freestyle). A runner would probably concur that the 800 meter (half-mile) run is one of the most painful races in that sport.

The highest lactate I have ever measured in myself, following a 200 IM race, was about 16 mM. I have measured higher levels in several Olympic swimmers, including 20.2 mM in one (as he was vomiting all over the pool deck – for reasons I’ll try to remember to explain in a subsequent post). On my bike, where I’m mostly using my legs, obviously, I think my highest recorded lactate measurement was about 12 or 13 mM following a set of ten 2-minute all-out hill repeats.

I measure my lactate levels using a different hand-held device from the one that measures glucose and B-OHB.

[Another parable, this time about marriage: 2 years ago my father asked me what my wife and I wanted for Christmas. I said “we” wanted a lactate meter with about 200 test strips (I think it was about $900 for everything). He looked at me funny, but figured I knew what I was talking about. When Christmas rolled around and “we” got “our” lactate meter I had to spend a few minutes explaining to my wife why this was a perfect gift for “us” as it allowed “us” to spend lots of time together while she pricked my finger for blood during my workouts. She didn’t really agree with me. I clearly don’t understand women very well – I really thought she would find this device “cool.” Which is why this is a blog about health, not marriage.]

Results from my experiment

Day 1: Saturday (hard swim workout, race pace)

This was a one hour, 45 minute swim with warm-up and cool down. The “main set” was mostly freestyle and butterfly at all-out race pace for distances of 25, 50, 75, and 100 yard intervals with long rest (1:2 – 2 times more rest than swim time) for the all-out 100 yard swims, and modest rest (2:1 – half the rest time of each swim). The single most demanding aspect of this workout took place with about 25 minutes remaining and, though I didn’t measure peak lactate, I suspect it was around 12-14 mM, based on the discomfort I experienced. I was surprised that my lactate level was still as high as it was (see below) 25 minutes later, though I suspect I didn’t cool down as gingerly as I should have, to optimize for maximum lactate clearance.

During this workout I consumed nothing and prior to the workout I consumed my usual 40 mL of medium chain triglyceride (MCT) oil.

At 7:29 am, just before beginning the workout, my glucose was 86 mg/dL, B-OHB was 0.7 mM (which is low for my fasting level), and lactate was 1.9 mM.

Immediately post-workout, at 9:14 am, my glucose was 118 mg/dL, B-OHB was 1.0 mM, and lactate was 7.2 mM.

Day 2: Sunday (long ride, 80% of race pace)

This was a tempo ride covering 104 miles (167 km) with 5,600 feet of climbing. Average pace was 17 mph (about 28 km/hr) with lots of headwind. My average HR over this 6 hour ride was 141 and average power output was between 190 and 200 watts. There were many sections of the ride, particularly on the climbs, where my HR was sustained in the 160’s for 30 minute stretches and power output was above 275 watts (which, for me, means my muscles generate lactate faster than my liver can clear it).

During this workout I consumed the following:

- Two single-serving packets (1 oz) of cream cheese (14 gm fat; 2 gm carb; 2 gm protein)

- 50 gm of super starch, by Generation UCAN mixed in my water bottles (50 gm super starch which, technically, is a carb but does not behave like one with respect to insulin secretion and ketone suppression – I will write a dedicated post on super starch in the future, but if you must try it now, use this code to get a discount: “UCANPA”)

- 2.5 oz of mixed nuts (25% of each almonds, cashews, walnuts, peanuts – 36 gm fat; 14 gm protein; 15 gm carb)

Total intake during 6 hour ride, therefore, was: 50 gm fat; 16 gm protein; 67 gm carb (of which 50 gm was super-starch), for a total of about 750 calories.

About 90 minutes prior to the ride I consumed 4 eggs fluffed with heavy cream, cream cheese, coffee with heavy cream, and my usual 40 mL of MCT oil.

At 7:56 am, my glucose was 88 mg/dL, B-OHB was 1.3 mM, and lactate was 1.7 mM.

Immediately post-ride, at 2:39 pm, my glucose was 74 mg/dL, B-OHB was 4.4 mM, and lactate was 2.2 mM.

Day 3: Monday (dry-land, high intensity training)

On this particular day, it was raining (one of 3 days a year this happens in San Diego), so I did not do the outdoor stuff (including tire flips).

Prior to the workout I consumed nothing other than my usual 40 mL of MCT oil and during the workout I consumed about 4 gm of branched chain amino acids (BCAA) and 10 gm of super starch mixed in my water bottle – so essentially just water.

Immediately prior to the workout, at 6:43 am, my glucose was 77 mg/dL, B-OHB was 3.5 mM*, and lactate was 1.6 mM.

At 7:52 am glucose was 132 mg/dL, B-OHB was 2.2 mM, and lactate was 5.4 mM.

*If you’re wondering why my fasting B-OHB level was so high (recall, I’m usually between 1.0 and 2.0), I suspect it’s at least a partial result of 2 things:

- Residual fat breakdown from the previous day’s long ride and caloric deficit, and

- On Sunday night I ate (no exaggeration) about half a gallon of my wife’s famous zero sugar, high fat coffee ice cream, which must be the closest thing I’ve ever experienced to heroin in terms of addiction potential.

Summary

The figure below summarizes the data from the mini-self-experiment I just described.

What can we learn about the interaction between glucose, B-OHB, and lactate?

How does super starch impact my ketosis?

Is ketosis helping me or hurting me?

Stay tuned for next week, when I will try to interpret these results…

Photo by James Thomas on Unsplash

Thank you, Peter, for responding. Re-reading my note, I see I might not have been clear that the knowledge is hoped for to help me personally do what I can to avoid my mom’s fate, not thinking the good science will be of help to Mom. Congratulations on NuSI, and bravo that you are pursuing knowledge that will change the world. Blessings.

Dr Attia,

Over the last few months, I’ve noticed a strange little pattern. Just wondering your thoughts…

If I work out daily, and maintain a high ketosis reading (between 60/80 on the ketositx), my weight loss tends to be slow, and plateau. I eliminate most of the carbs to get the high reading. Workouts include a 40 minute run, then weights and cardio strength. Total workout around 1.5 hours, intense, 4- 5 times a week.

If I DON’T workout, BUT keep myself in ketosis at a lower reading (trace amounts of ketones, up to around 20/30), my weight on the scale starts to drop. During this time, I usually am adding a bowl of berries and cream to my diet at the end of the day, accounting for the lower reading.

Assuming that in scenario 1 when I’m working out, I’m NOT adding the exact weight back in muscle as to keep the scale even, any thoughts on what might be happening? I suppose simple coincidence can be an answer as well. Just trying to figure the best long-term strategy.

Thanks,

Shawn

…oh, and not asking advice “medically-speaking”, to be clear. Just asking if there’s a nutritional ketosis factoid that might line up with that. I gave the URL to my MD and we talk about all this stuff, FYI.

I am frustrated at my blood ketone blood levels. I have been on low carb (<50 g) now for several weeks. I have lost weight during this time. However, I just got a blood meter and have been disappointed at the ketone levels after exercise. I do short, high intensity cardio three days a week and short, high intensity weight training three days a week. As an example, today I did 25 minutes of fast, "can't do one more rep" weight training that puts me in an anaerobic state for about 30 seconds after each set. When I am done I consume about 40 g of whey protein because I feel my muscles need to rebuild from the workout. I then eat a high fat meal of eggs, butter, coconut oil and cream for breakfast. About an hour after my workout I tested my blood ketone level, and it was only 0.3. I don't understand why this is so low. Is this because my workouts are too intense? Does it make a difference how long after a workout I test ketone levels? Thanks for any help you can give me.

Couple of things….yes intense workout suppresses ketone production and/or contributes to net utilization resulting in lower levels. See my series on the interplay of exercise and ketosis.

Also, don’t fixate on ketosis unless you have a real need to be there. You can be perfectly fine without being in ketosis. So be sure you know why you’re trying to get there.

Have you been checking your blood glucose as well, post-workout?

Per Peter’s advice to self-test, I have been monitoring myself extensively on BG/B-Ketone levels just before, just after, and an 60-90 minutes after exercising (sometimes I take superstarch just after exercise, sometimes not—so far that appears to make little difference with my numbers). I mainly do weight lifting (HIIT style) and running (8-9 minute pace), 4-6 miles. I have probably a dozen such tests under my belt now; I want to double or triple that and run some statistics on it before I feel sure of my impressions.

That said, here is where my data about myself is pointing me right now: I find that lifting blunts ketosis and spikes blood glucose the most for me, and that the shorter the lift, the “worse” the effect, in general. For example, I will see a post-workout BG of 120-180 mg/dL (from 70-90 mg/dL pre) and B-ketone drop of 30-50%. An hour later, the BG especially drops back, though usually not back to baseline. The B-Ketone level usually recovers much more slowly. The same effect is true of running to a lesser degree: shorter runs mean higher blood glucose and lower B-ketones at the end. And having a lower post-workout blood glucose definitely means that, an hour or so later, my blood glucose and B-ketones are usually a lot ‘better’ than they would be after a short workout. For reference, for me, a short workout would be 25-30 minutes. For lifting, a longer workout would be 35-40 minutes (that extra 10 minutes can make a big difference for me). For running, a short run would be 30 minutes, a long one would be 45 minutes or more. If I run for over an hour (which is rare), usually my numbers improve by the end of the workout and get even better an hour later (B-ketones up, BG down from pre-workout). As far as I can tell, high B-ketone levels are driven by heavy fat burn, so things that amplify that (like long workouts that really empty liver glycogen and require very a lot of fat burning) help a bunch.

I’ve only been kicked out of ketosis once (down to 0.4 mmol/L), after doing a workout in very mild ketosis. I was only ‘out’ for a few hours. So I can’t speak to having that “issue” often, but I did want to say that, in my experimentation with nutritional ketosis and monitoring myself daily, I am finding that, almost regardless of what I eat (within the limits of 50g carbs per day or so), I can have spectacular ketosis (>2.5 mmol/L B-ketones) or very modest or low ketosis (0.8-1.0 mmol/L B-ketones). The thing that distinguishes the two states for me personally is exercise. On days that I exercise, the next morning I will be deep in ketosis. On days that I don’t, it’s usually not so great. Skipping 2-3 days of exercise leads to high fasting BG for me (85-95 mg/dl as opposed to ~70 mg/dl) and low fasting B-ketone levels for me.

The upshot of that is that, in my personal experience over the last few months, physical exertion is a huge contributor to awesome blood sugar levels and heavy ketosis—even when it causes acute, temporary aggravations to these measurements during and shortly after exercise. So, my suggestion would be to MAYBE extend your exercise time by ~10 minutes, but regardless, to check your ketone levels before exercise and at a different interval post-workout—2 hours after, and also the next morning. See if you notice a pattern there.

Also, one final note from me—it took me six weeks (!) of ketogenic eating to see my athletic performance recover to the point where my exercise was as good as before on a high-carb diet. I didn’t have the blood ketone tests available at that point, so I don’t know how that was. All my above numbers were taken after being in virtually uninterrupted ketosis for over 2 months. I definitely recommend sticking with the ketogenic diet for several months if you really want to see what it’s all about. I liked the diet from the start, but exercising was miserable and frustrating for, as I said, 6 weeks for me. After that passed, everything seemed better for me. Good luck, and thanks for sharing your experience. It’s interesting to read about how ketosis works for others.

Good Afternoon Dr. Attia,

Thank you for your excellent and inspiring work (and research).

I wonder if you would write an article in the short future 🙂 about what happens to the Cori Cycle once a person has been keto-adapted. I ask because I practice Chinese (internal) martial arts that requires me to hold diffucult postures from long periods of time which activate the Cory Cycle. This in turn, leads to the acumulation of internal power (that’s why they are called internal martial arts).

I haven’t found anything on the Internet about it. Do keto adapted athletes still rely on the Cori cycle or something else kicks in?

Thank you,

Sam

The Cori Cycle is still in effect in ketosis. This week I’ll be publishing a detailed post on ketosis.

Thank you Sir!

Both insulin and glucose (probably by causing the secretion of insulin) suppress ketones. This is why, for example, consuming more than about 50 gm of carbohydrates per day and/or more than about 120-150 gm of protein per day makes it difficult to be in nutritional ketosis – too much insulin secretion.

Is that total carbs or net carbs?

At the 50 gm level, this is closer to total.

This study https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17848941 suggests some people may compensate for energy expenditure through exercise more so than others, and greater weight loss may be observed in those that do not have a compensatory effect from exercising. Maybe exercise induced weight loss may be effective in some, but not others.

Quick question if you have 15 seconds:

I have been in NK for about 3 weeks now(as shown by Ketone Blood sticks; avg ~ 2mm).

After energetic 30 min Cardio work(rope work mostly) my Blood Glucose which otherwise averages ~82, goes upto ~100. Does this indicate Ketosis is not fully achieved yet? I was expecting the energy expenditure to all come fat, I suppose.

Thanks in advance!

Indy M.

Sunnyvale, CA

I reread your post(Part II) and the Glucose appears to be coming from my Liver, when I workout at a pretty high Heart rate. So the answer is found.

I need to vary my workouts and check against the four/five heart rate zones I utilize, namely Aerobic threshold, Tempo, Sublactate threshold, Lactate threhsold and sometimes Aerobic Capacity(all Joel Friel’s terminology). It would be interesting know how the Hepatic Glucose output varies with the different Heart Rate Zones.

Thanks again.

Nope. It’s hepatic glucose output. I did a tough 90 minute workout yesterday at 8 am (fasted). I ingested nothing but water during the ride. Glucose went from 85 to 135 by end of the ride (lactate was about 5 mM and B-OHB when from 1.9 mM to 0.6 mM).

”

Nope. It’s hepatic glucose output. I did a tough 90 minute workout yesterday at 8 am (fasted). I ingested nothing but water during the ride. Glucose went from 85 to 135 by end of the ride (lactate was about 5 mM and B-OHB when from 1.9 mM to 0.6 mM).

”

Those numbers are in the ball park of what I am seeing. It is amazing that the Liver is managing to squirrel away enough Glycogen in spite of my <= 20 gms of Carb a day!

Thank you very much! Thats good to know. I hope to find out by experimenting in what heart rate zone I have least Glucose rise/most Ketone fall. Hopefully in one of the midzones, say Tempo, which is close to my Marathon speed.

Thanks for all your help.

Indy M.

At some point, I’ll report on my latest metabolic self-experiments. I’m learning more by the day.

I am currently in the starting phase of entering ketosis, but there is a question of mine that remains unanswered. I do strength training regularly, both for health reasons and to get stronger, and I wonder what kind of effect ketosis has on that. I know a lot of people who work out to build a lot of muscle use ketosis as a way of losing excess fat after “bulking up”, but I wonder about all the other implications. More specifically:

1. Is ketosis efficient at conserving muscle mass when eating at a caloric deficit? The body burning fat but not muscle, that is.

2. Compared to a glycolytic diet, how easily does the body build muscle while in ketosis when eating at a caloric surplus? When not eating carbs, it would seem to me that the body doesn’t put on fat that easily, but unless you excrete the caloric surplus, it appears that the excess calories must be stored on the body in some way.

Hope you have the time to answer, and thanks a lot for all the information and all the articles on this site! It really is of a different level than the average opinions of people in the dieting/bodybuilding scene.

Kindest regards, Nicholas T.

1. Not sure. I would not imagine it’s “best” or even “optimal,” but it’s certainly possible. Just yesterday I set a new record for fastest 6 consecutive flips of the 450 pound tire. Obviously, there is more to that than pure strength, but this is pretty demanding.

2. The key, for me, is timing of protein ingestion. How much BCAA…when I take them…how much glutamine…when I ingest it…what kind of post-workout protein…how much… etc.

Alan Aragon said something along the lines of: fat adaption can potentially impair performance by reducing the activity pyruvate dehydrogenase which could thereby decrease the rate of glycogenolysis during times of high glycogen demand. Interesting, as I would guess that fat adaption, even on a moderate carb diet, would be beneficial for athletic performance. Have you read any studies on this?

Thanks Peter

Not sure what the evidence is supporting this claim. One of the main defects in insulin resistance is just that (impaired flux through PDH), especially at the neuron. So I’m not sure how PDH impairment is being documented. Also, one would need to define “fat adaptation” a bit more rigorously to have this discussion. My definition may be different than yours.

Peter,

You said, “In your case, I’d be curious to see what would happen to your BP if you did not, at least temporarily, supplement with sodium.”

I’ve been ketotic ~8wks (<=30g) drinking copious amounts of sea salt in order to avoid feeling plagued. Salt works but, my bp has jumped to 143/86 from 127/80.

If you had to bet, would say that it is more likely this happened due to 8 weeks of inactivity (physiological stress due to adaptation and mental stress due to finals) or over-supplementation of salt?

Btw., def agree on that it takes at least a few miles to rev up. Wow, never thought I'd corroborate such subtleties. You are the man.

Hard to say, but you may consider only supplementing sodium (and magnesium) around long workouts, but not routinely.

Peter, thank you. I would actually never supp. sodium, if it weren’t for utter malaise I feel without it (or something else). Even being sedentary is difficult under 30g of carbs for me. 8 weeks into nutr. ketosis and I still feel like I am “hitting the wall” 8-10hrs into any sedentary day (a dehydrated, nauseated, head-ache feeling). There is almost nothing I can do to stay up at that point; and I used to pull all-nighters back to back just 2 months ago. It’s like there is something fundamentally wrong with this ketotic metabolism. Anyway, I really appreciate your input. These random pangs of seeming “imbalance” are just getting frustrating, esp. for my workouts.

Hello Alec, I had somewhat similar experience – even with months on ketogenic diet and huge weight loss I had high fasting blood glucose (90-100) and similar feelings you had before dinner…

Few days ago I started to measure blood ketone levels, which were not that high (<1) and I started to supplement more coconut oil (2 tbsp). Within two days my ketones went over 3, few times maxing at 5 and in two days my fasting blood glucose did significantly fall down (60-70), as well as hunger etc. All of that with exactly the same diet.

Possibly some people need that extra push that normal fat alone doesn't do… BTW, urine ketone strips max out after this change, before I had them in the middle of the scale. I will keep it like that for few weeks and then see if it's permanent…

It is common training dogma that a large post-workout dose of carbs can capture transient high levels of glycogen synthase in order to increase muscle glycogen beyond baseline. This is thought to better prepare the athlete for their next training session. If on a carb restriction diet and therefore without this dose, do you feel that high glycogen levels can be achieved by other means?

Thanks for the excellent website and your humble approach to the science.

I’m less convinced of the timing need, or the so-called “window” effect. If the liver or muscle are deplete of glycogen, they will always have metabolic priority to replenish in the face of available CHO, long before DNL kicks in. Most people, of course, dramatically over-estimate how much CHO is necessary to “load” the system.

Peter.

I do apriciate all the hard work you are doing in educating us.

In this blog entry you have answered to Nicholas Tidemann on March 18, 2013 with an answer saying: The key, for me, is timing of protein ingestion. How much BCAA…when I take them…how much glutamine…when I ingest it…what kind of post-workout protein…how much… etc.

Would you be so kind and elaborate this? I am a pretty lean person and enjoying ketosis but I want to gain more muscle mass and gain strenght, stay in ketosis and also eat naturally, as my main goal is longevity and a productive life. I also wonder how come you are using supplements BCAA and glutamine when both can come from correct diet. Do you do this just because its less time consuming?

Dare, to address this properly requires an entire post, unfortunately. It will happen at some point.

Thanks for a fast reply Peter, I cant imagine you still have time to answer us and doing everything else.

One more question thou. I am still in doubts about builing muscle on a keto diet. Do you know anything about how process of builing muscle works and do you recommend any literature to me, about it? My biggest concern is that it is impossible (or at least very hard) to build muscle if glycogen stores are not full. The way I look at it, using only my regular Joe logic, is that after a hard workout body’s primary function around muscles is to refill the glycogen stores first (beside other – more important stuff) and only later it will go and build new tissue, does this makes sense or its completely off? I know timing is not an issue so its not mandatory to do this in 30min window (like most bodybuilding sites recommend), but if im on a keto diet I wonder how fast can we convert fat/protein to carbs and use that to refill glycogen?

Dr. Peter,

If you’re primarily keto-adapted and you’re glycogen levels are depleted, how would you ‘top off’ the tank before a big event when you’re daily intake is ~50g/day? How exactly would you do that to ensure that you can last 10-12 hours just under Aerobic Threshold? Once that is set, sounds like SuperStarch pre-race and during is a smart practice to go along with electrolytes and some onboard fat supplementation like nuts and other fat portables. Hoping you can comment on this.

Thanks,

Jeremy

I use the actual delta of carb requirement to top of glycogen stores. Sometimes this is more than 50 gm/day. If I’ve estimated correctly (i.e., that I needed more than ~50 gm/day), I stay in ketosis.

how long did it take restricting carbohydrates before you were consistently in ketosis? I have personally restricted carbs to <30g/day for the past 11 days. Today I had coffee with heavy cream, and then a lunch of italian sausage, red peppers, spinach in a home made tomato sauce, and my post prandial ketones 75 min later were .2mmol/L. I was expecting 1-3mmol/L. I'm wondering if there is something you did that I have not done to get my body into ketosis. Thanks.

You are likely consuming too much protein. Switch to ketosis should take no more than 3 or 4 days.

Question: Post 40mile ride/then 6 mile run/with weight lifting in the middle did precision test for glucose and ketones. Did eat four hundred calories of coconut oil/butter/cocoa candies I make with stevia and two ozs of cheese to replenish protein within 30 minutes of getting home and testing.

Glucose 168! Ketones 1. How concerned should I be? Is this a byproduct of ketosis (>100 days) combined with intense exercise? My fasting glucose is usually 75 and post meal glucose 110 at one hour.

Hey Peter.. have you interpreted the results yet?

Yes, I think so. Addressed in recent posts.

I have been on LCHF for the last 5 years. However, for the last 4 weeks I’ve been eating to minimize insulin as much as possible to get a bit leaner. I would like to get to about 7% body fat.

I eat according to the following rules. Rule 1 may override rule 2 and rule 2 may override rule 3 etc.

1. Eat 100 grams of protein on days with 1 workout, closer to 150 grams on days with 2 work outs. Do not go over or under these numbers.

2. Eat protein only when insulin is low. Insulin levels can be approximated by blood glucose or ketones.

3. Do not eat more than 50 grams of protein per meal. Closer to 30 grams is ideal.

4. When hungry eat fat.

I also eat 1 tomato covered in salt at each meal.

I go to the gym and lift weights 8-10 times a week (sometimes twice a day).

I have huge amounts of energy all the time and even after my hour session is up I usually would like to keep going. I spend the whole day behind a computer and if I do not go to the gym that day I feel uncomfortably energetic. I often train having not eaten dinner the night before and not having eaten breakfast that morning. In this case I find my ketones are super high, I am very thirsty in the gym but there is no decrease in energy what so ever. One more thing, on a diet with a bit more protein and carbs (but still what most consider low carb) I would always get light headed after performing big exercises like squats or dead lifts, this never happens anymore.

There certainly is an adaptation phase every time you lower carbs+protein but after you get past that you will never look back. I am a fat burning machine.

Very interesting experience, Emil. Thanks for sharing.