You’ll recall from last week’s post I did a self-experiment to see if I could learn something about the interplay of exercise and ketosis, at least in myself. To understand this discussion, you’ll want to have read Part I of this post.

However, before getting to this, I want to digress and briefly address two unrelated issues:

- Some of you (about 67 or 68 as of this writing) have sent me various links to news reports released yesterday reporting on a study out of Harvard’s School of Public Health. I was planning to eventually write a post about how observational epidemiology is effectively at the heart of the nutritional crises we face – virtually every nutrition-based recommendation (e.g., eat fiber, don’t eat fat, salt is bad for you, red meat is bad for you) we hear is based on this sort of work. Given this study, and the press it’s getting, I will be writing the post on observational epidemiology next week. However, I’m going to ask you all to undertake a little “homework assignment.” Before next week I would suggest you read this article by Gary Taubes from the New York Times Magazine in 2007 which deals with this exact problem.

- I confirmed this week that someone (i.e., me) can actually eat too much of my wife’s ice cream (recipe already posted here –pretty please with lard on top no more requests for it). On two consecutive nights I ate about 4 or 5 bowls of the stuff. Holy cow did I feel like hell for a few hours. The amazing part is that I did this on two consecutive nights. Talk about addictive potential. Don’t say I didn’t warn you…

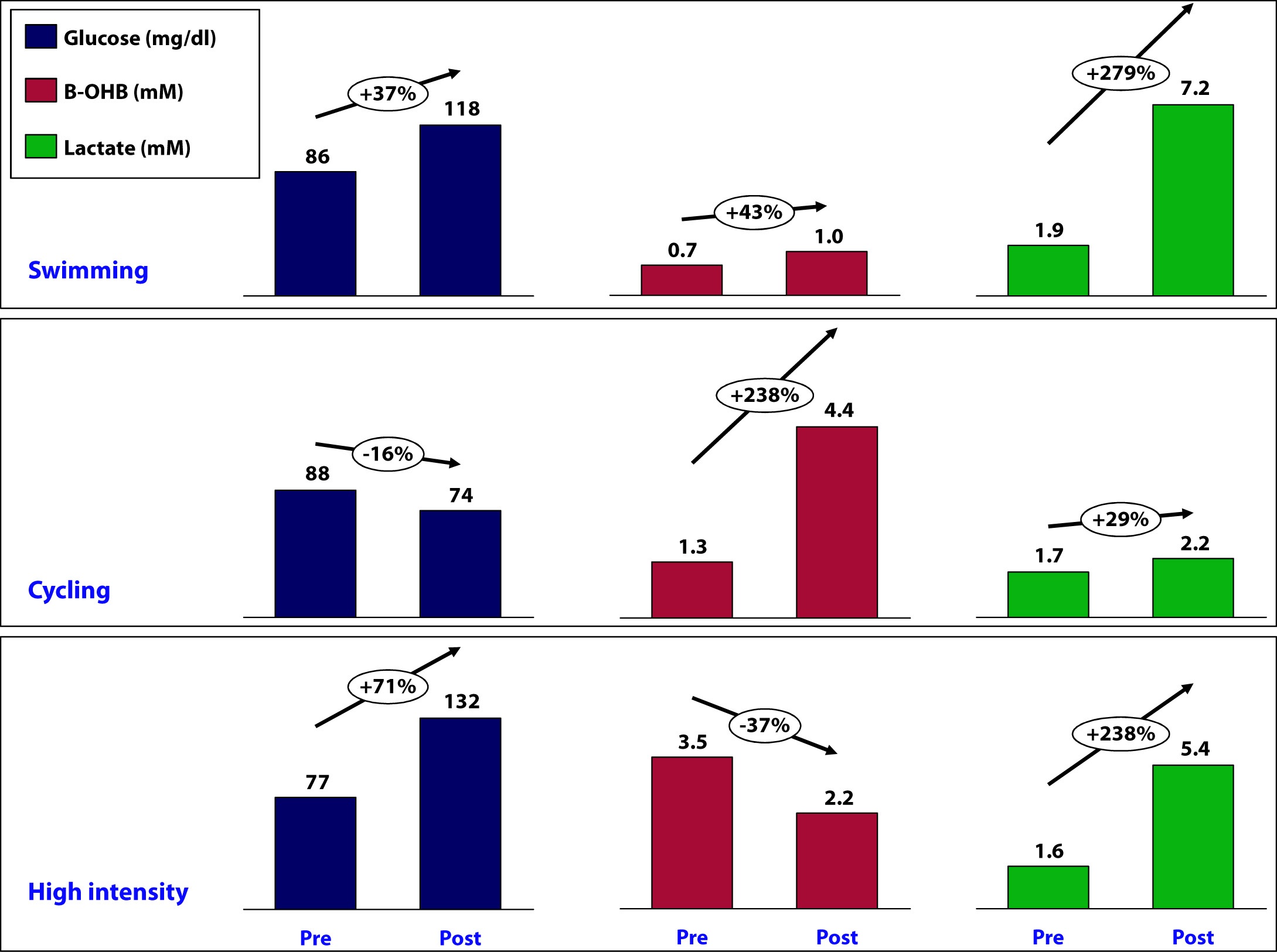

OK, back to the purpose of this post: How is ketosis impacting my ability to exercise? Here is the summary of the results from my personal experiment:

Let’s take a closer look at what may have been going on in each workout and see what we can learn.

Swimming

This workout probably produced the most lactate of the three workouts (we don’t know for sure because I only measured immediate pre- and post- levels without measuring in-workout levels). My glucose level rose by nearly 40% during this workout despite the fact that I did not consume anything.

How does this happen? Our bodies store glucose in the liver and in muscles in a “storage” form (a long chain of joined glucose molecules) called glycogen.

Whenever our bodies cannot access sufficient cellular oxygen, our metabolism shifts to a less efficient form of energy acquisition called anaerobic catabolism. During these periods of activity, we cannot oxidize fat or glycogen (i.e., use oxygen to harness the full chemical potential of fat or carbohydrate molecules). I will be writing in much more detail about these ideas in the next month or so, so don’t worry if these ideas seem a bit foreign right now. Just know that sometimes our bodies can convert fat or glucose to energy (efficiently), and sometimes we can only convert glucose to energy (inefficiently).

Because of my ketosis, and the metabolic flexibility that accompanies it, I only “require” that my body turn to glucose for energy under the most “stressful” forms of exercise – like I was doing a lot of during this workout. But keep in mind, my muscles CANNOT export one gram of the glucose they store, so any glucose in my bloodstream is either ingested (which I didn’t do) or coming from my liver, which CAN export glucose.

Furthermore, the stress of a workout like this results in my adrenal glands releasing a set of chemicals called catecholamines, which cause my liver to export even more of its stored glucose via a process called hepatic glucose output (HGO).

[As an aside, one of the major defects in type-2 diabetes is the inability of insulin to suppress HGO. In other words, even when not under the catecholamine stress that “should” lead to HGO, their livers constantly export glucose, which contributes to elevated blood glucose levels. The very popular drug, metformin, used often in type-2 diabetes, blocks this process.]

While I did experience a pretty large rise in lactate (almost 3x), my ketones still went up a bit. This could imply a few things:

- Elevated lactate levels do not directly inhibit beta-hydroxybutyrate (B-OHB)

- Mild elevations in glucose do not directly inhibit B-OHB

- Mild elevations in glucose do not directly inhibit B-OHB, if insulin is being suppressed (as is the case during vigorous exercise)

- B-OHB was suppressed, but we are only appreciating the net effect, which was a small increase (i.e., because of my MCT oil and activity, B-OHB levels were rising dramatically, but the rise was blunted by some other factor, such as HGO, insulin, and/or lactate)

More questions than answers from this workout, so on to the next workout.

Cycling

Despite this being a tough ride at several points, on average it was less stressful than the other two workouts and I spent the greater fraction of time in my aerobic to tempo (zone 2 to zone 3) zones.

A ride like this, however, is a great example of the advantages of improved metabolic flexibility that accompanies nutritional ketosis. My average heart rate during this 6 hour ride was 141. Prior to becoming ketotic, at a HR of 141 my respiratory quotient (RQ) was about 0.98, which meant I was almost 100% dependent on glycogen (glucose) for energy. Today, at a HR of 141 (with the same power output), my RQ is about 0.7 to 0.75, which means at the same HR and same power output as prior to ketosis, I now rely on glycogen for only about 10% of my energy needs, and the remaining 90% comes from access to my internal fat stores.

This is an important point. I will devote future posts to this topic in more detail, but I wanted to use this opportunity to mention it.

So what happened physiologically on this ride?

- My glucose levels fell, probably because I was slowly accessing glycogen stores for peak efforts (once my HR reaches 162 I become 50% dependent on glycogen) throughout the ride (e.g., peak climbing efforts, hard sections on flats), but my liver was not “called on” to dump out a massive amount of glucose in response to a catecholamine surge (and if it was, at some point during the ride, that amount of glucose had been used up by the time I was finished).

- B-OHB levels increased by about 2.5x – to 4.4. mM, which is pretty high for me. My highest recorded B-OHB level was 5.1 mM (also after a long ride). This confirms what my RQ data indicate — my body almost entirely relies on fat oxidation for energy for activity at this intensity. In the process, B-OHB is generated in large quantities, both for my brain and also my skeletal muscles (e.g., leg muscles). In reality, cardiac myocytes (heart muscle cells) also “like” B-OHB more than glucose and probably also access it when it is abundant.

- Lactate levels by the end of the ride were effectively unchanged though. Based on “feel,” I suspect I hit peak lactate levels of 8 to 10 mM on this ride during peak efforts, but I had ample time to clear it.

A few observations:

- I consumed 67 gm of carbohydrate on this ride (of which 50 gm was Generation UCAN’s super starch), yet this did not appear to negatively impact my ability to generate ketones. Technically, we can’t be sure this is the case, since I would have needed a “control” to know this (e.g., my metabolic and genetic twin doing and eating everything the same as I did, but without the consumption of super starch and/or without the bike ride). It’s possible that super starch did slightly inhibit ketosis and that my B-OHB level would have been, say, 5.0 mM instead of 4.4 mM. Metabolic studies of super starch show that it has a minimal impact on insulin secretion and blood glucose levels, hence the name “super” starch.

- Whatever impact peak levels of lactate production and hepatic glucose output had during the ride, they seem blunted by the end of the ride (and the ride did finish with a modestly difficult 1.4 mile climb at 6-7% grade, which I rode at a HR of about 150).

Since neither lactate levels nor glucose levels (nor insulin levels by extension) were elevated, I can’t really draw any conclusion about whether one factor, more than any other, suppressed production of B-OHB, so on to the next workout.

High intensity training

This sort of workout spans the creatine-phosphate (CP) system and the anaerobic energy system, and probably involves the aerobic energy system the least. I’ll write a lot about these later, but for now just know the CP system is good for very short bursts of energy (say 10-20 seconds) and recall the previous discussion of aerobic and anaerobic catabolism. In other words, this is the type of workout where my nutritional state of ketosis offers the least advantage.

- This workout saw the greatest increase in glucose level, about 70%. It is important to recall that during this workout I ingested water with a small amount of branched chain amino acids (BCAA’s – valine, leucine, isoleucine) and super starch, about 4 gm and 10 gm, respectively. I do not believe either accounted for the sharp rise in blood glucose and, again, I believe hepatic glucose output in response to a strong catecholamine surge attributed to this increase.

- Lactate levels also rose, though probably less so than during a peak swim effort. This suggests more of the effort in this workout was fueled by the CP system (versus the anaerobic system, which probably played a larger role in the swim workout).

- This was the only workout that saw a fall in B-OHB levels, which now offers some insight into what might be impacting B-OHB production.

Contrasting this workout with the swim workout draws a pleasant contrast: both saw a similar rise in lactate, but one saw twice the rise in blood glucose. In the former, B-OHB was unchanged (actually rose slightly), while in the latter, B-OHB fell by over a third.

This suggests – but certainly does not prove – that it is not lactate per se that inhibits ketone (B-OHB) production, but rather glucose and/or insulin. It is possible the BCAA played a role, and if I was thinking straight, I would not have consumed anything during this workout to remove variables. But I have a very hard time believing 3 or 4 gm of BCAA could suppress B-OHB. When you see hoof prints in the sand, you should probably think of horses before you think of zebras.

Conversely, there is some evidence that lactate promotes re-esterification of fatty acids into triglycerides within adipose cells. What does that mean in English? High levels of lactate take free fatty acids and help promote putting them back into storage form. This would prevent free fatty acids from making their way to the liver where they could be turned into ketones (e.g., B-OHB). In other words, we may be missing this effect because of my sampling error – I only sampled twice per workout, rather than multiple times throughout the workout.

So what did I learn, overall?

I think it’s safe to say I did not definitively answer any questions, which is not surprising given the number of confounding factors, lack of controls, and sample size of one. However, I think I did learn a few things.

Lesson 1

The metabolic advantages of nutritional ketosis seemed most apparent during my bike ride, evidenced by my ability to access internal fat stores across a much broader range of physiologic stress than a non-ketotic individual. (More on this in Lesson 4.)

Lesson 2

The swim and high intensity dry-land workouts suggested that my state of nutritional ketosis did not completely impair my ability to store or export hepatic glucose. This is a very important point! Why? Because, it runs counter to the “conventional wisdom” of low-carb (or ketotic) nutrition with respect to physical performance. We are “told” that without carbohydrates we can’t synthesize glycogen (i.e., we can’t store glucose). However, those who promote this idea fail to realize that glycerol (the backbone of triglycerides) is turned into glycogen, along with amino acids, not to mention the 20 to 40 gm of carbohydrates I consume each day (since my brain doesn’t need them). We know muscles still store glycogen in ketosis, as this has been well studied and documented via muscle biopsies by Phinney, Volek, and others. But, my little self-experiment actually adds a layer to this. Because muscle can’t export glucose (muscle lacks the enzyme glucose-1-phosphatase), we know that the increase in my blood glucose was accounted for by HGO – my liver exporting its glycogen. In other words, ketosis does not appear to completely impair hepatic glycogen formation or export. Again, we’d need controls to try to assess how much, if any, hepatic glycogen formation and/or export is inhibited. It’s hard to make the argument that being in ketosis is allowing me to swim and do high intensity training with greater aptitude, and as I’ve commented in the past, I feel I’m about 5-10% “off” where I was prior to ketosis for these specific activities, but at the same time, I could be doing more to optimize around them (e.g., spend less time on my bike which invariably detracts from them, supplement with creatine which may support shorter, more explosive movements), which I am not.

Lesson 3

Consuming “massive” amounts of super starch (50 gm on the ride), did not seem to adversely affect my ketotic state. My total carbohydrate intake for that day, including what I consumed for the other 18 hours of the day, was probably close to 90 gm (50 gm of super starch plus 40 gm of carbs from the other food I ate). This suggests one or two possibilities:

- Because of the molecular structure of super starch (I’ll be discussing this in the future, so please hold questions) and the concomitant metabolic profile that follows from this structure, it may not inhibit ketosis like other carbohydrate, and/or

- During periods of profound physical stress insulin secretion is being sufficiently inhibited that higher-than-normal amounts of carbohydrate can be tolerated without negatively impacting ketone production.

This is pretty straightforward to test, even in myself. I just haven’t done so yet.

Lesson 4

While it’s probably the case that my liver has less glycogen (i.e., stored glucose) at any point in time, relative to what would be present if I were eating a high-carb diet, it’s not clear this matters, at least for some types of workouts. Why? Take the following example:

- Someone my size can probably store about 100 gm of hepatic (liver) glycogen and about 300 gm of muscle glycogen at “full” capacity. This represents about 1600 calories worth of glucose – the most I can store at any one time.

- Before I was ketotic, my RQ at 60% max VO2 (about 2,500 mL of O2 per min consumption) was nearly 1.00, so at that level of power output (a pace I can hold for hours from a cardiovascular fitness standpoint) I required 95% of my energy to come from glycogen. So, how long do my glycogen stores last? 2,500 mL of O2 per minute translates to about 750 calories per hour, so I would be good for about 2 hours and 15 minutes on my glycogen stores.

- Contrast this with my ketotic state. Let’s assume my glycogen stores are now only half what they were before. Muscle biopsy data suggests this is probably an overly conservative estimate, but let us assume this to be the case. Now I only store 50 mg of hepatic glycogen and 150 gm of muscle glycogen, about 800 calories worth of glucose.

- In ketosis, my RQ at 60% max VO2 is 0.77 (at last check), telling me I am getting only 22% of my energy from glucose and the remaining 78% from fat. So, how long do my depleted glycogen stores last? Nearly 5 hours. Why? Because I barely access glucose at the SAME level of oxygen consumption and the same power output.

I know what you’re thinking…why is this an advantage? Just consume more glucose as you ride! It’s not that simple, but you’ll have to wait until my upcoming post, “What does exercise have to do with being in the ICU” to find out.

Going back to the black sheep example I open Part I of this post with, we know that at least one person in nutritional ketosis seems to make enough liver and muscle glycogen to support even the most demanding of his energetic needs.

Photo by Troy Oldham on Unsplash

Hi Peter,

Thanks for all the info. Have not parsed all of it. Also an MD via Canada, currently in SF. Am wondering if you have any thoughts on Ketosis and Altitude +/- Diamox. Have just recently embarked

on the ketosis/low carbohydrate journey and exercise and am looking for shortcuts. Am going on a 5 day backpacking trip to Giant Sequoia and going to try and maintain my diet. Altitude ranges from 8,000 feet at the start sleeping in 10-12,000 range with a 14,000 peak over 4 days… Will be taking Diamox(never AMS but just want to try it) and NSAID- recent Stanford study with Iburofen. Of concern was that study with military that showed soldiers with 70% carb diet did better with less AMS. Wondering if you have any pearls of wisdom and really if should forgo ketosis/diet for this brief interlude. I understand if you won’t be able to reply in a timely or material manner.

Many Thanks,

A.

Funny you should ask. I just got back from a very intense bike training week in Colorado, which included most major climbs between 12,000 and 14,000 feet (including Mt. Evans). While anecdotal, I had heard that ketosis was a superior state for elevation. In my case, this turned out to be exactly true. I suffered no AMS, despite having no time to acclimate and felt shockingly strong at elevation, especially relative to others. While most of the riders I was with were much stronger than me, the gap seemed much narrower at elevation. Not sure what to make of it.

Thanks Peter,

Update: Interesting experience, but too many confounding variables to tease out the most likely etiology which may just be simple and common. The week before I had gone backpacking, I had tried some Nattokinase/ Serropeptase which I noticed had a diuretic effect. I felt like I was in Ketosis formost of the day (just butter and MCT oil in the morning) and would use UCann with exercise-mostly cycling. I do notice I lack a certain oomph at what I presume anaerobic threshold but lack of fitness

is also a variable.

I wanted to try Diamox to see how I would do on it in case I went to higher altitudes and to see if it was advantageous. I started with 125mg BID 48 hours beforehand and increased to 250mg BID, 24 hours prior to driving to 8-9000 ft at Mineral King in Giant Sequoia . I did notice a diuresis, less appetite,

a loss of a pound or two, and ate less. I increased added salt empirically and wondered if eating less would be beneficial… Upon arrival, I seemed to be adjusting well to altitude and less fatigued than my confreres(one a sports medicine doc from UCSD).

The first day was a killer. Despite the lightest pack I have ever carried- close to 40 lbs., I struggled. I just didn’t have the legs, much like cycling up the first hill-no legs. A friend took some weight but the long day continued including a 1-2 hour grind up some scree at Sawtooth Pass which seemed more of an anaerobic endeavour. We went down to Glacier Pass and over to Silver Lake… I realize I was over normal fatigue but not anything I hadn’t done before. That night I started eating the pasta and couscous being cooked… The next day went better over Blacrock Pass into Big Five Lakes but still fatigued….

About 24 hours post the first day exertion, I got myoglobinuria. Though tired, I didn’t feel that untoward nor particularly achy. ECF wise I seemed well hydrated, and had been sucking on a Camelbak all the way up the passes. That night I drank about 3 litres of water, ate carbs with extra added salt and stopped the diamox. By morning it had mostly cleared with some minor episodic discoloration. Over the next couple of days I continued to regain strength to about half. I didn’t know what to make of it, I suppose perhaps I was hypovolemic at least intra-cellularly, had been on a PPI-omeprazole, and was in a ketotic state at least the first day. I know they use diamox sometimes as a treatment for rhabdomyolysis probably just to avoid renal precipitation but confounding overall. I certainly won’t use diamox again unless necessary. Back at sea level, apart from normal fatigue, I feel fine and haven’t objectified any measurements, and back on my normal routine. Never had myoglobinuria before even at higher altitudes-highest being 20,000 ft. An interesting anecdote.

87Scott

August 30 19:16

Ketone Help. I started LCHF 6 weeks ago. Immediately dropped 10 pounds and need to plateau as it continues to decrease. I’m super active cycling and working out 5 to 6 days a week.I got the meter and tested Glucose (out of curiosity)20 min after a meal sugars at 70, the next day (yesterday) tested Ketones mid day 0.3. Today I blood tested first thing in a.m. and Ketones are 0.6, which sounds very low. I appear to exhibit all the signs of being in Ketogenic state, no food cravings, frequent urination (which is decreasing, thankfully) was keeping carbs less that 50 per day, now somewhere between 50 and 100. Extra are pre, post and during more intense cardio. work (2 to 4 hours). I’ve definitely lost strength in regard to cycling, hoping it will return??

What does low Ketone blood measure mean in regard to Ketogenic state?

What other fats can I eat to avoid continued weight loss (I may be eating too much protein now?)

And the big question, how does the body utilize fuels in an Anaerobic state if there aren’t adequate sugars availabe for fuel???

Thask for any input…

It would be interesting to hear how you fared. In theory, in a ketotic state, you don’t have easy access to pyruvate which would generate energy in the anaerobic mode, mainly in the circumstances of weightlifting and climbing long hills on a bike. How did time and more training play out for you?

https://www.genr8speed.com/endurance/vitargo.php

Is the vitrgo s2 a super starch as well?

No. Only Generation UCAN has the IP to make super starch. Others just use amylopectin or waxy maize, but don’t hydrothermally treat.

Problem: A pro-cyclist might burn 5500 calories in training everyday. Even if they’d be getting 80% of energy from fat, that still leaves 1100 calories from glycogen – daily. So how could a professional cyclist possibly be keto-adaptive?

A pro cyclist could likely tolerate more carb/protein to remain keto-adapted, given their enormous expenditure.

I just wanted to say thank you. I was inspired to give low carb/high fat way of eating a try. I raced on Sunday in Amsterdam (two weeks after changing my eating) and I had a great day full of energy, despite not eating any gel or drinking sports drink. It was tough to break through the sports-nutrition-dogma. But this method worked for me!

Wow, that’s actually unusual. Good for you. Most people do not adapt that quickly. I sure didn’t…

I should add the change was dropping carbs from about 100-150g/day to <50 and increasing the amount of fat. Moving out of the "wobble" zone has been very satisfying so far. I'm looking forward to seeing how this works for my 25k race next month, and next year's cycling season too. Thanks for taking the time to produce the superstarch video – really interesting and will help me explain this to my friends.

Hi Peter,

I run the risk of oversimplifying things here, but doesnt the introduction of UCAN at least in theory ELIMINATE any sort of trade-off between aerobic efficiency vs top-end power? So you can be in ketosis but as long as you keep your glucose levels topped up using UCAN you can still be very competitive in lets say sprint or olympic distance triathlons which – lets face it – are at threshold for 80% of the race and above threshold for the remainder.

Alex

Yes, that was my original reason to start experimenting with it over a year ago. Could I get some of the glucose I was missing, without inhibiting ketosis…

So have you found that you have regained some of your top-end power after starting to use UCAN vs in the past when you relied mainly on ketones?

Perhaps that could be a great experiment for the future – give a placebo and UCAN to a fully keto adapted athelete at two different sessions and test performance at threshold intensities

I definitely feel my top end is better this year than one year ago…but I can’t honestly say I know which factor or factors have contributed, and to what extent. If I had to speculate, I’d guess that adaptation has continued and I’m getting more efficient with less substrate. I think UCAN plays a role, but it’s hard for me to parse out exactly how much, because my metabolic state is already putting me a low insulin environment, so UCAN’s help may be just incremental in me (vs. more pronounced in others). Agree with your idea for an experiment.

Hey Peter

Forgive me if you’ve covered this but I am still unsure of the way ketones reflect fat loss. If my blood ketones are low (.2-.4) could I still be burning fat?

Thanks for all you do!

Yes, one need not be in ketosis to burn fat. Ketosis just means you’re produce enough B-OHB to offset your brain’s need for glucose.

Hi Peter,

My question is in regards to how long it actually took your body to adapt to a high volume training regime while making the switch to a keto-adapted state. I am asking you for the following reason:

I’m in my first month of keto adaptation, and made sure it coincided with my off-season in triathlon to give my body a chance to make some adaptations “at rest” before starting to build up volume again.

Last week I went for a 4hr fun ride in the mountains, it was my first long ride since starting the new diet so didnt really know what to expect. I was happy to find my energy levels steady (just one LCHF bar during the ride and some nuts) though I found my climbing power to be absolute rubbish.

Today I went for a low intensity/aerobic 80 mile ride on flat terrain. It was going great for the first half with no hunger or need to refuel and somewhat decent output but after the 3hr mark the wheels started to come off. I had another LCHF bar and kept replenishing with water which got me back home through another 1.5hr of being in a very fatigued, low energy/cursing my existence type state (couldnt just stop cause I was another 30 miles from home). Once I got home I could hardly stand up without getting dizzy and found it hard to even take a shower while standing or cook my post-workout meal. Please note I had 400mg sodium before the workout and another 500 or so during.

Once I ate my post-workout meal (LCHF) I immediately felt better but I still felt a bit “off” for the remainder of the day.

What has your experience been when starting out? I may have gone a bit too hard on cold turkey here so will try to take a bit more fuel with me next time but did you find yourself feeling like this sometime in the initial phase? Will it gradually start getting easier? Maybe I was too low on sodium? Anyone else had any similar experiences?

Apologies for the long post

It’s been so long now, that I’m sort of forgetting, but I think it took about 12 weeks to really adapt. Maybe even longer to get the last 10%.

I am trying to get me head around what you are saying about higher glucose levels and lower B-OHB levels after a high intensity workout. When I do HIIT my glucose levels rise about 75% post workout from pre workout. My B-OHB levels post workout are relatively low (0.3 to 0.6). Does the fact that there is hepatic export of glucose during high intensity workouts mean there is an elimination or significant reduction in ketosis, and if so for how long? Or are both happening simultaneously? In contrast when I do a moderate bike ride (65-70% of max heart rate) my B-OHB levels usually are a full point higher than after a high intensity workout. Does the low level of B-OHB (sometimes <0.5) after a high intensity workout mean that I am not fully keto adapted or is it a function of the intensity of the workout. Or both?

Yes, HGO raises overall glucose levels, which raises insulin levels, which lowers B-OHB. How long this lasts is not entirely clear, but it seems to be dependent on duration of exercise, intensity, and maybe a few other factors.

Firstly, thanks SO MUCH for the hard work you put into his blog! The amount of information here is staggering and I’m only beginning to scratch the surface. A percentage is somewhat over my head but when I put in the effort, I learn a lot.

My question is a little off-topic for this thread but it relates to something you said above:

“Furthermore, the stress of a workout like this results in my adrenal glands releasing a set of chemicals called catecholamines, which cause my liver to export even more of its stored glucose via a process called hepatic glucose output (HGO).

[As an aside, one of the major defects in type-2 diabetes is the metformin, used often in type-2 diabetes, blocks this process.] ”

I have been in constant ketosis for a couple of months now and the transformation in my health is ASTOUNDING, energy, mental clarity etc. I’m convinced this is THE way to go! After having had a myriad of vague health problems that so often plague 40ish women, I now feel decades younger.

The question is: a friend mentioned he is on Metformin to promote and support longevity. I can certainly see the theory in this but if I understand correctly, it seems to be a vague substitute for the conditions created by a ketogenic state. ( I would assume that if someone who was in ketosis took metformin they would experience a potential hypoclycemic crisis?)

Am I correct in the (simplificated) understanding that a healthy, non-diabetic person taking metformin may assert some protective measures against glucose/insulin effects in the modern north-american diet so therefore it has at least some similarity to being in ketosis? I instinctively feel that ketosis is a superior state but I’m not sure I could explain why.

Thanks again!!

Lisa

Great question, Lisa. There is strong epidemiologic data suggesting that “prophylactic” use of metformin (i.e., someone who is not T2D but takes it) may be protective of several diseases, including cancer. In fact, I know a number of non-diabetic cancer researchers who take metformin prophylactically for this reason. Of course, no RCT data support this, but the mechanism does make sense, if you believe that more HGO leads to more insulin and IGF.

My husband and I were prescribed Metformin for preventive reasons by a cutting-edge lipidologist. after our NMRs. We were both prescribed 2000 daily. He is taking 2000; however, I had such horrible side effects that I stopped taking it. (We are taking the best brand for minimal side effects, so changing brands won’t help.) I was wondering Peter, if in your experience, there are people who just can not tolerate it. I started with a very low 250 and was instructed to increase gradually, but even at that level side effects were terrible. Our doctor who you know and respect, takes 2000 per day herself for prevention. I think it is important to take it. I was wondering, not in my personal case, but in general, if you have seen this problem and what the cut-off point is with patients who have persistent side effects…how long to give medication a try and at what point the patient is determined to be intolerant. I am aware of the many benefits you mentioned about metformin. Thank you! maryann

I do know that some folks can’t tolerate it, with nausea being the most common side effect. One option, if your doctor feels it’s helpful, would be to reduce the dose to 1000 mg. I’m not sure the drug has any efficacy below 1000 mg, though maybe ramping up could help.

I’m at 250, but thanks. You’re right, efficacy is at 1500-2000. I was just interested in knowing at what point to give up trying…how long to wait before expecting side effects should be gone. Thanks again for your kind help.

Hi Peter – Thanks for all this great information.

I’ve regularly been in ketosis for the past couple of years and recently invested in a blood ketone meter. I conducted an n=1 experiment recently to figure out the amount of fat I can consume withouth significantly affecting my post prandial triglyceride levels. I’ve posted about this experiment on the Track Your Plaque forum if you have access :

https://www.trackyourplaque.com/forum/topics.aspx?ID=12824

Briefly, I measured TG’s, blood ketones and blood sugar, upon waking, 1 hour, 2 hours, 4 hours and 5 hours post “breakfast”. Breakfast consisted of 25gm LEF Whey Protein, 5gm psyllium husk, 8oz water and 45gm of “high oleic” safflower oil, coconut oil, butter or olive oil.

The results surprised me. Safflower oil had the least effect, followed closely by butter. I noticed that as my level of ketones increased so too did the TG levels – mild exercise seemed to reduce the levels after a period and I wondered if you’ve noticed anything similar i.e. your exercise prevents negative effects of higher TG’s.

I’m planning on repeating the same experiment using MCT oil, almond oil and high oleic sunflower oil.

I’m regularly in and out of ketosis with eating 60-80gm carbs – I wondered if you consider it likely more beneficial to stay one way or the other rather than flip-flop between the two?

Cheers!

Very interesting results, Dave! Thanks so much for sharing. I wonder, exactly, what is going on? The MCT will likely increase ketosis, but I do wonder about the impact on TG. PLEASE do keep me (us) posted. BTW – what did you pay for your TG meter?

Hi Peter- I’ll keep you posted. The next series of tests will most likely be early in the New Year. I just placed an order for the TG strips. I use a Cardiochek PA meter which cost me iro $600 five years ago. The results have generally compared well with lab results and I’ve found it useful to be able to test my cholesterol on a weekly basis to help assess dietary changes. There is also the regular Cardiochek meter which now retails for around $90 and is probably just as good as the professional version when it comes to testing individual levels i.e. TG or HDL or total cholesterol. I purchased mine from https://www.testsymptomsathome.com/ but they do come up regularly on ebay at good prices. Cheers!

The only thing I’d want to check is trig, so looks like the $90 version + trig strips would be good.

Peter,

I am on day 35 in ketosis and it is awesome, my experimenting has lead to a full life change. I am finally at the point where I can pick up the speed again. My running tests have all been fasted and I laugh the whole run in amazement; it is incredible. The other day I ran a 21 mile run with about 3,500′ of climbing. Three hours into the run I had a Stinger Waffle, I was also told that I could eat a carb or two mid run and wouldn’t kick me out. Once it hit my blood, I felt like a rock star and had an awesome kick for the last mile at 6:40 pace. This is not typical for a training run.

I am running a 10k this weekend and want to go full throttle. My gut is telling me to eat a gel or something prior to the race. I feel that I will have plenty of carbs stored, will I? I was suggested to eat a full 50g of carbs the night before including a sweat potato. I am planning on running under 40 minutes and my heart rate will be maxed.

Dan.

Dan, let us know how it works!

Well, I was talking with my buddy the night before the 10k and he said that I have enough glycogen stored in my muscles to last me for at least 1.5 hours, so I didn’t eat a gel. But since I was peer-pressured to run hard, a ‘friend’ placed a bet on me – thanks buddy, I didn’t think it was enough. So 60 minutes before the race I had an espresso (typical) and 30 minutes before I drank a UCAN cocktail. Now I felt for this short of a race, the UCAN might not influence my performance, but I didn’t think it would hurt me. I guess it was mostly psychological. Also, I did have a yam with dinner the night before, still maintaining my 50g carb limit.

The Results: I ran 40:22 which is 4.5 minutes faster than last year’s 10k; I have only run two 10ks ever. I am 42 years old and only been training (running) for two years now. Hmmm, so many variables? The Wednesday before, I had a gym workout that really beat me up. It didn’t seem hard at the time, but I felt it right up to race morning. I took three ibuprofen (not typical) prior to the race; that is how sore I felt and also shows how smart I am. The first thing I noticed, which was not typical, was that I did not have a finishing kick at all and I always have a kick – a strong kick. Aside from the first mile, which was a bit fast, my pace was the most stable ever, which also could be the reason I did not have a kick. I don’t think that taking a gel would have improved my performance; in fact I would bet that I would have had a slower time due to a fluctuating pace. It is hard to say.

I have a 5k coming up in a week and haven’t run one since high school without a pushing a stroller. I plan on eating a yam the night before and an espresso morning of. I am shooting for a sub 19 . . . we will see.

You’ll go under 19 with the right speed work. 800 meter repeats are your friend.

I am 48, I’ve been eating more or less Paleo (about 85%) for the past two years and am on day two of VLC. My hands and feet are swelling quite a bit. I always have some pitting edema in my legs by the end of the day, but generally my rings are loose, however, they started feeling a little tight yesterday and are appreciably so today.

I’m using https://paleotrack.com/journal to track my food, and according to it I’ve had 21g (4%) of carbs, 1417 mg of Potassium and 2530 mg of Sodium so far today. I workout 5 days a week, Crossfit with a strength emphasis.

I drink one large coffee with heavy cream every morning, and nothing but water for the rest of the day. Do you have any idea what would be causing this?

Finally got ‘Keto adapted’ (about 2.3 on the Meter today) after ~3 weeks of <= ~40 gms of Carb/day. After a few days, I want to introduce UCAN(10-20gms) for Dinner, in a soup, and see if that takes me out of NK. I have been trying to incorporate UCAN into my regular meals and increase my hydration at the same time. If it does not take me out of Ketosis, that will be a big help and a big find! (Don't like to cook at night ;)).

Indy M.

Keep us posted. Remember, though, you can’t heat the UCAN product or the hydrothermal processes reverses and the superstarch reverts to just plain old waxy maize.

“Peter Attia February 12, 2013

Keep us posted. Remember, though, you can’t heat the UCAN product or the hydrothermal processes reverses and the superstarch reverts to just plain old waxy maize.”

No, I did not know that. I thought I read thru the package material carefully enough. Many many thanks, I will try my experiments without applying heat to the UCAN powder.

Check directly with them. I don’t recall the temperature (maybe 110 F) at which it basically reverts to (now very overpriced) waxy maize.