Want to catch up with other articles from this series?

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part I

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part II

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part III

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part IV

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part V

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part VI

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part VII

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part VIII

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part IX

Previously, in Part I and Part II of this series, we addressed 4 concepts:

#1 — What is cholesterol?

#2 — What is the relationship between the cholesterol we eat and the cholesterol in our body?

#3 — Is cholesterol bad?

#4 — How does cholesterol move around our body?

Quick refresher on take-away points from previous posts, should you need it

- Cholesterol is “just” another fancy organic molecule in our body but with an interesting distinction: we eat it, we make it, we store it, and we excrete it – all in different amounts.

- The pool of cholesterol in our body is essential for life. No cholesterol = no life.

- Cholesterol exists in 2 forms – unesterified or “free” (UC) and esterified (CE) – and the form determines if we can absorb it or not, or store it or not (among other things).

- Much of the cholesterol we eat is in the form of CE. It is not absorbed and is excreted by our gut (i.e., leaves our body in stool). The reason this occurs is that CE not only has to be de-esterified, but it competes for absorption with the vastly larger amounts of UC supplied by the biliary route.

- Re-absorption of the cholesterol we synthesize in our body (i.e., endogenous produced cholesterol) is the dominant source of the cholesterol in our body. That is, most of the cholesterol in our body is made by our body.

- The process of regulating cholesterol is very complex and multifaceted with multiple layers of control. I’ve only touched on the absorption side, but the synthesis side is also complex and highly regulated. You will see that synthesis and absorption are very interrelated.

- Eating cholesterol has very little impact on the cholesterol levels in your body. This is a fact, not my opinion. Anyone who tells you different is, at best, ignorant of this topic. At worst, they are a deliberate charlatan. Years ago the Canadian Guidelines removed the limitation of dietary cholesterol. The rest of the world, especially the United States, needs to catch up. To see an important reference on this topic, please look here.

- Cholesterol and triglycerides are not soluble in plasma (i.e., they can’t dissolve in water) and are therefore said to be hydrophobic.

- To be carried anywhere in our body, say from your liver to your coronary artery, they need to be carried by a special protein-wrapped transport vessel called a lipoprotein.

- As these “ships” called lipoproteins leave the liver they undergo a process of maturation where they shed much of their triglyceride “cargo” in the form of free fatty acid, and doing so makes them smaller and richer in cholesterol.

- Special proteins, apoproteins, play an important role in moving lipoproteins around the body and facilitating their interactions with other cells. The most important of these are the apoB class, residing on VLDL, IDL, and LDL particles, and the apoA-I class, residing for the most part on the HDL particles.

- Cholesterol transport in plasma occurs in both directions, from the liver and small intestine towards the periphery and back to the liver and small intestine (the “gut”).

- The major function of the apoB-containing particles is to traffic energy (triglycerides) to muscles and phospholipids to all cells. Their cholesterol is trafficked back to the liver. The apoA-I containing particles traffic cholesterol to steroidogenic tissues, adipocytes (a storage organ for cholesterol ester) and ultimately back to the liver, gut, or steroidogenic tissue.

- All lipoproteins are part of the human lipid transportation system and work harmoniously together to efficiently traffic lipids. As you are probably starting to appreciate, the trafficking pattern is highly complex and the lipoproteins constantly exchange their core and surface lipids. This is a big reason why measuring how much cholesterol is within various lipoprotein species will in many circumstances be so misleading, as we’ll discuss subsequently in this series.

Concept #5 – How do we measure cholesterol?

All this talk about cholesterol probably has some of you wondering how one actually measures the stuff. Much of the raw content I’m going to present here is actually material I’ve had to learn recently. One of the best resources I’ve found on this topic is the text book Contemporary Cardiology: Therapeutic Lipidology, in particular, chapter 14 by Tom Dayspring and chapter 15 by Bill Cromwell and Jim Otvos. Anyone aspiring to be a lipid savant like these three pioneers probably ought to get a copy. The other book that tells this story well is The Cholesterol Wars: The Skeptics versus the Preponderance of Evidence. For most folks, however, I’m hoping this series is sufficient and I’ll do my best to get the important points across.

As far back as the 1940’s scientists understood that cholesterol and lipids could not simply travel freely within the bloodstream without something to carry them and obscure their hydrophobicity, but it certainly wasn’t clear what these carriers looked like.

The initial breakthrough came during the Second World War when two researchers, E.J. Cohn and J.L. Oncley at Harvard developed a complex and elaborate technique to fractionate (i.e., separate) human serum (serum is blood, less the cells and clotting factors) into two “classes” of lipoproteins: those with alpha mobility and those with beta mobility. [“Alpha” versus “beta” mobility describes a pattern of movement seen by different particles, relative to fluid, under a uniform electric field, which is the essence of electrophoresis.]

You’ll recall that LDL particles are also called “beta” particles and HDL particles are also called “alpha” particles. Now you see why.

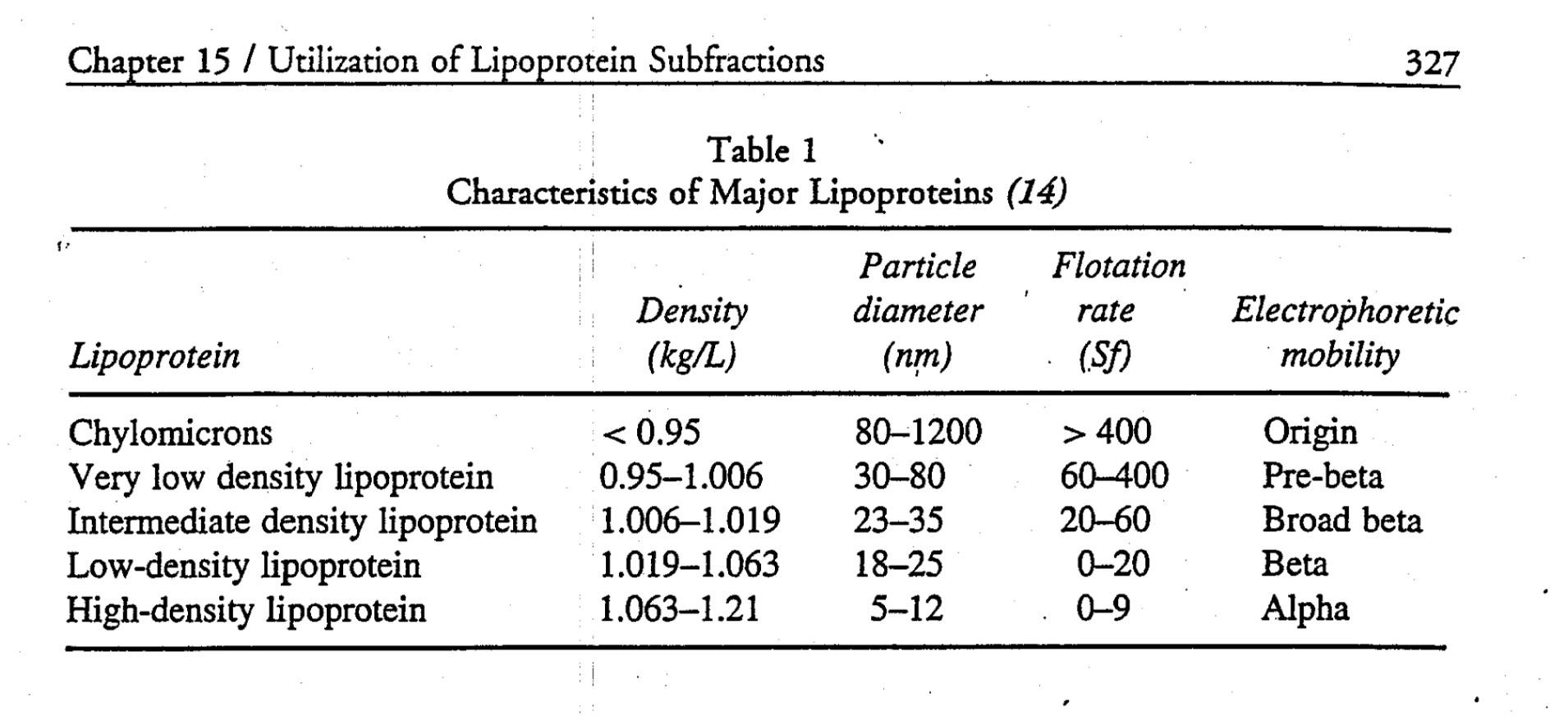

This work set the stage for subsequent work, by a physicist named John Gofman, using the techniques of preparative and analytic ultracentrifugation to fully classify the major classes of human lipoproteins. The table below summarizes what was gleaned by these experiments.

Cool, huh? Well, sort of. While this was an enormous breakthrough scientifically, it didn’t really have an inexpensive and quick test that could be used clinically the way, say, one could measure glucose levels or hemoglobin levels in patients routinely. What became crucial with Gofman’s discovery is that lipoproteins were now a recognized entity and they got their names according to their buoyancy: very low density, intermediate density, low density and high density.

There is more interesting history to this tale, but let’s fast-forward to where we are today. When you go to your doctor to have your cholesterol levels checked, what do they actually do?

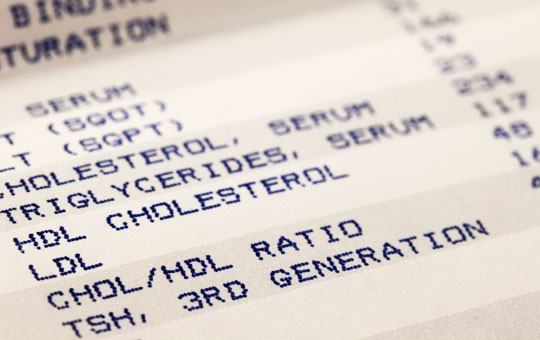

Let’s start at the finish line. What do they report? The figure below is a representative result. It reports serum cholesterol (in total), serum triglycerides, HDL cholesterol (i.e., HDL-C), LDL cholesterol (i.e., LDL-C) and sometimes non-HDL-C (i.e., LDL-C + VLDL-C). But where do these numbers come from?

Blood is drawn into a tube called a serum separator tube (SST) and immediately spun in centrifuge to separate the blood from “whole blood” into serum (normally clear yellow, top) and blood cells (dark red, bottom). A gel film, from the SST, separates the serum and blood cells, as shown below. The tube is kept cool and sent from the phlebotomy lab to the processing lab.

As early as the 1950’s scientists figured out clever chemical tricks to directly measure the content of total cholesterol in the serum. The chemical details probably are not interesting to non-chemists, but I was able to find a great paper from 1961 that details the methodology. The point is this: initially it was only possible to measure the total content of cholesterol (TC), or concentration to be technically correct, in plasma. By that I mean it is the total mass (weight of all the cholesterol molecules) of cholesterol trafficked within all of the lipoprotein species that exist in a specified unit of volume: in the United States, we measure this in milligram of cholesterol per deciliter of plasma abbreviated as mg/dL, or in the rest of the world as mmol/Liter or mmol/L. Why? Think back to our analogy from last week:

Cholesterol is a passenger on a ship — the “ship,” of course, being a lipoprotein particle. The early methods of measuring cholesterol had to break apart the hull of the ship to quantify the cargo. The assays to do so, like the one described above, were pretty harsh. If you had a bunch of LDL ships, HDL ships, VLDL ships, and IDL ships, these assays ripped them all apart and told you the sum total of the cargo. Obviously this was a great breakthrough in the day, but it was limited. From this assay, one could conclude, for example, that a person had 200 mg/dL of cholesterol hiding out in all their lipoprotein particles.

Good to know, but what next? It turns out there were two other important factors that could be measured directly in blood: triglycerides and the cholesterol content within the HDL particle, HDL-C. Early on laboratories could easily separate apoA-I-containing particles (i.e., HDL) from the apoB-containing particles (i.e., VLDLs, IDLs and LDLs), but they could not easily and economically separate the various apoB-containing particles from one another. A full description of these methods is not necessary to appreciate this discussion, but for those interested, methodologies can be found here (TG) and here (HDL-C).

Important digression for context

What becomes critical to understand for our subsequent discussions is that the apoB particles have the potential to deliver cholesterol into an artery wall (the problem we’re trying to avoid), and 90-95% of the apoB particles are LDL particles. Hence, it is LDL particle number (LDL-P or apoB) that drives the particles into the artery wall. Thus, physicians need to be able to quantify the number of LDL particles present in a given individual. For decades there was no way of doing that. Then LDL-C (read on) became available and it served as a way (not entirely accurate, but nonetheless a way) of quantitating LDL particles.

Back to the story

How can one figure out the concentration of cholesterol in the LDL particle? As you may recall from last week, LDL is the “ship” that carries the most cholesterol cargo. More importantly, as I mentioned above, it is also the key ship that traffics cholesterol directly into the artery wall. Thus, there has always been an enormous interest in knowing how much cholesterol is trafficked within LDL particles.

For a long time it was not possible to directly measure LDL-C, the cholesterol content of an LDL particle. However, we did know the following had to be true:

TC = LDL-C + HDL-C + VLDL-C + IDL-C + chylomicron-C + remnant-C + Lp(a)-C

where X-C denotes the cholesterol content of a respective cholesterol-carrying particle. There are 2 particles in the equation above that I didn’t specifically mention last week, the remnant particle and the Lp(a) particle (pronounced “EL – pee – little – a,” which sounds less silly than, “Lip-a”). Lp(a) is an LDL-like particle but with a special apoprotein attached to it, aptly called apoprotein(a), which is actually “attached” to the apoB molecule of a standard LDL particle. Think of Lp(a) as a “special” kind of LDL particle. As we’ll learn later in this series, Lp(a) particles are bad dudes when it comes to atherosclerosis.

“Remnants” are nearly-empty-of-triglyceride particles of chylomicrons and VLDL. In essence they are larger TG-rich particles that have lost a lot of their TG core content as well as surface phospholipids and are thus smaller than, or remnants of, their “parent particles.” Hence,they are cholesterol-rich particles. Under fasting conditions, in a not-too-terribly-insulin-resistant person, IDL-C, chylomicron-C, and remnant-C are negligible. Furthermore, in most people Lp(a)-C does not exist or is not very high.

So we’re left with this simplification:

TC ~ LDL-C + HDL-C + VLDL-C

which is clearly an improvement in convenience over the first equation. But what to do about that pesky VLDL-C?

There are a number of variations, but essentially a breakthrough (mid 1970s) formula, called the Friedewald Formula, estimates VLDL-C as one-fifth the concentration of serum triglycerides (some variants use 0.16 instead of one-fifth, or 0.20). This assumes all TG are trafficked in one’s VLDL particles and that a normally composed VLDL contains five times more TG than cholesterol.

Rearranging the above simplified formula we have:

LDL-C ~ TC – HDL-C – TG/5

Let’s plug in the numbers from the above figure, as an example. TC = 234 mg/dL; HDL-C = 48 mg/dL, and TG = 117 mg/dL. Hence, LDL-C is approximately 234 – 48 – 117/5 = 163 mg/dL.

Kind of a long run for a short slide, huh? Perhaps, but it is important to understand that when you go to your doctor and get a “cholesterol test,” odds are this is exactly what you’re getting.

Therefore LDL-C can be estimated knowing just TC, HDL-C, and TG, assuming LDL-C matters (hint: it doesn’t matter much in many folks).

Furthermore, what if the LDL particle is cholesterol-depleted instead of its normal state of being cholesterol-enriched? Unfortunately, especially in an insulin resistant population (i.e., the United States), both TG content within lipoproteins and the exchange of TG for cholesterol esters between particles is very common, and using this formula can significantly underestimate LDL-C. Worse yet, LDL-C becomes less meaningful in predicting risk, as I will address next week.

What about direct measurement of LDL-C?

To chronicle the entire history of direct LDL-C measurement is beyond the scope of this post. Many companies have developed proprietary techniques to measure LDL-C directly, along with apoB, and ultimately LDL-P. I’ll address two “major players” here: Atherotech and LipoScience.

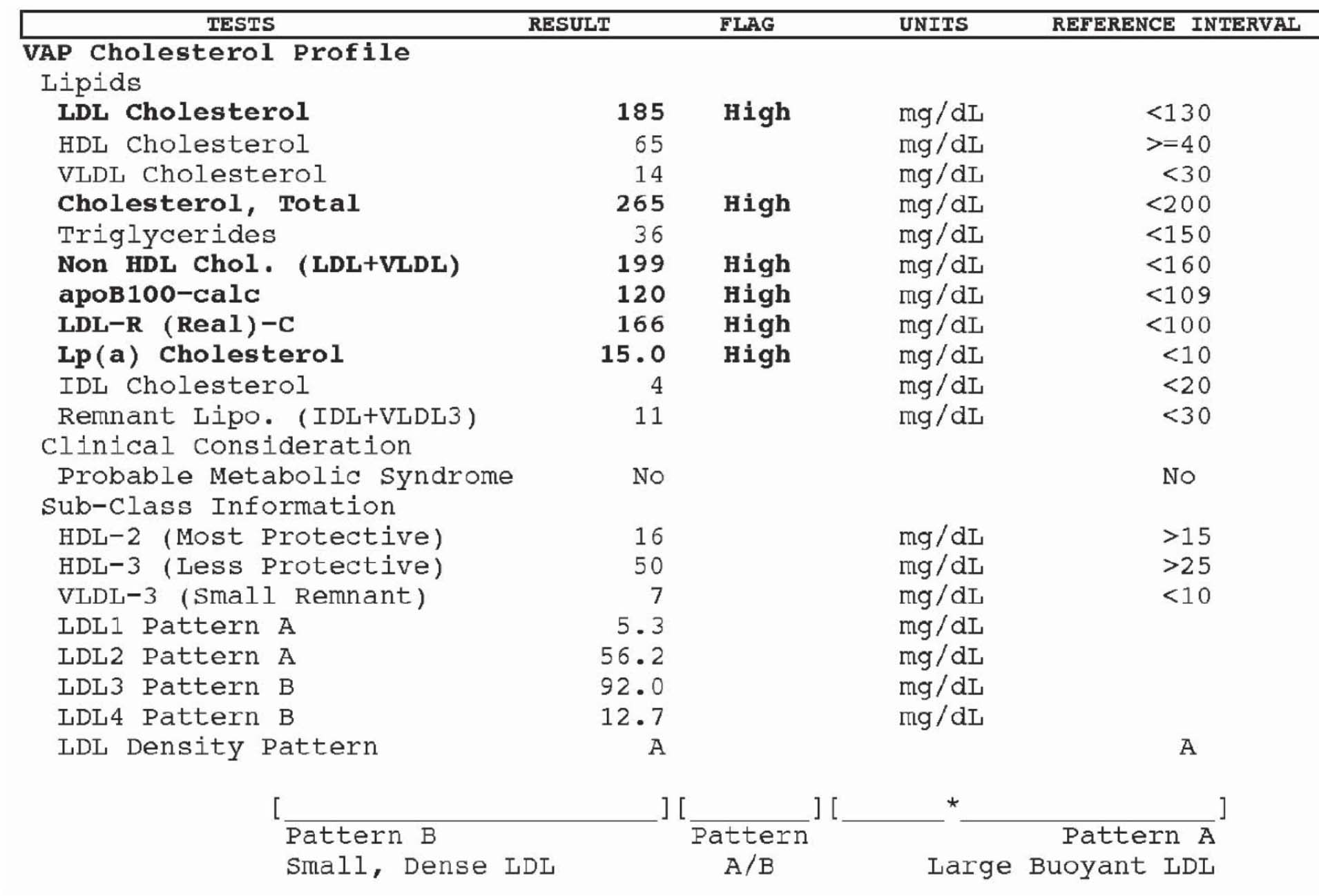

Atherotech developed an assay, called a VAP panel (VAP stands for Vertical Auto Profile) to do everything described above, but also to directly measure the amount of cholesterol contained within the LDL particle. Furthermore, they have developed assays to directly measure the cholesterol in IDL particles, VLDL particles, and even Lp(a) particles. Below is a snapshot of how VAP reporting looks.

A couple of things are worth mentioning:

- Subparticle cholesterol content information is also generated, including 2 different classes of HDL particles (HDL-2, HDL-3) and 4 different classes of LDL particles (LDL-1, LDL-2, LDL-3, LDL-4).

- LDL particles, based on the subparticle information, are classified as “pattern A,” “pattern B,” or “pattern A/B.” Pattern A implies more large, buoyant LDL particles, while pattern B implies more small, dense LDL particles.

Remember, though, while cholesterol mass concentration numbers may correlate with the number of particles, they often do not. They only convey the mass concentration of cholesterol molecules within all of the particle subtypes per unit of volume. VAP tests do not report the number of LDL or HDL particles, but they do attempt to estimate atherogenic particle number (apoB) using a proprietary formula based on subparticle cholesterol concentration and particle sizes. I should point out that the formula, to my knowledge, has not been validated in any study and not published in a peer reviewed journal.

A high estimate of apoB100 (i.e., what the VAP reports) is said to correlate with the actual measurement of apoB. Since apoB is found on each LDL particle, this serves as a proxy of LDL-P. The American Diabetic Associate and the American College of Cardiology Consensus Statement on Lipoproteins and the new National Lipid Association biomarker paper stipulates that apoB must be done using a protein immunoassay, not an estimate, such as that of VAP.

But how can one actually count the number of LDL particles and HDL particles?

There are several methods of doing this, but only one company, LipoScience, has the FDA approved technology to do so using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, or NMR for short. The other available methodologies are ion mobility transfer and ultracentrifugation (by Quest) and separation of LDL particles with particle staining (by Spectracell). Virtually all guidelines (e.g., ADA, ACC, AACC and NLA) only advise LDL-P via NMR at this time.

NMR, which is the basis for not only how to count lipoprotein particles, but also diagnostic tests such as MRI scans, is really one of my favorite technical topics. In residency I wrote a surgical handbook and on page145-146, if you’re interested, you can read a brief description of how MRI technology works, which will explain how NMR technology can actually count lipoprotein particles.

As an aside, and just to give you an idea of what a great sport my wife is, I wrote this surgical handbook over the course of a year while in residency. To do so, I had to read approximately 8,000 pages of surgical textbooks and try to distill them down to just this 160 page summary. Doing so required reading about 22 pages every day while working about 110 hours per week, typical of a surgical residency “back in the day.” Besides exercising, I spent every single moment of my “free” time reading for and writing this handbook. Finally, a few months into it, my wife asked, “Why the hell are you doing this? You never watch TV, you never go out, you never do anything else!” I responded that it was the best way I could learn this material, but also, that I wanted to have a legacy when I left residency. Half joking, I asked her, “What’s your legacy?” Blank stare. A few months later, for Valentine’s Day, she gave me this t-shirt. I think it’s safe to say not a single person has read this handbook. So much for my legacy…

A brief explanation of how NMR works to count (and measure) particles can also be found here.

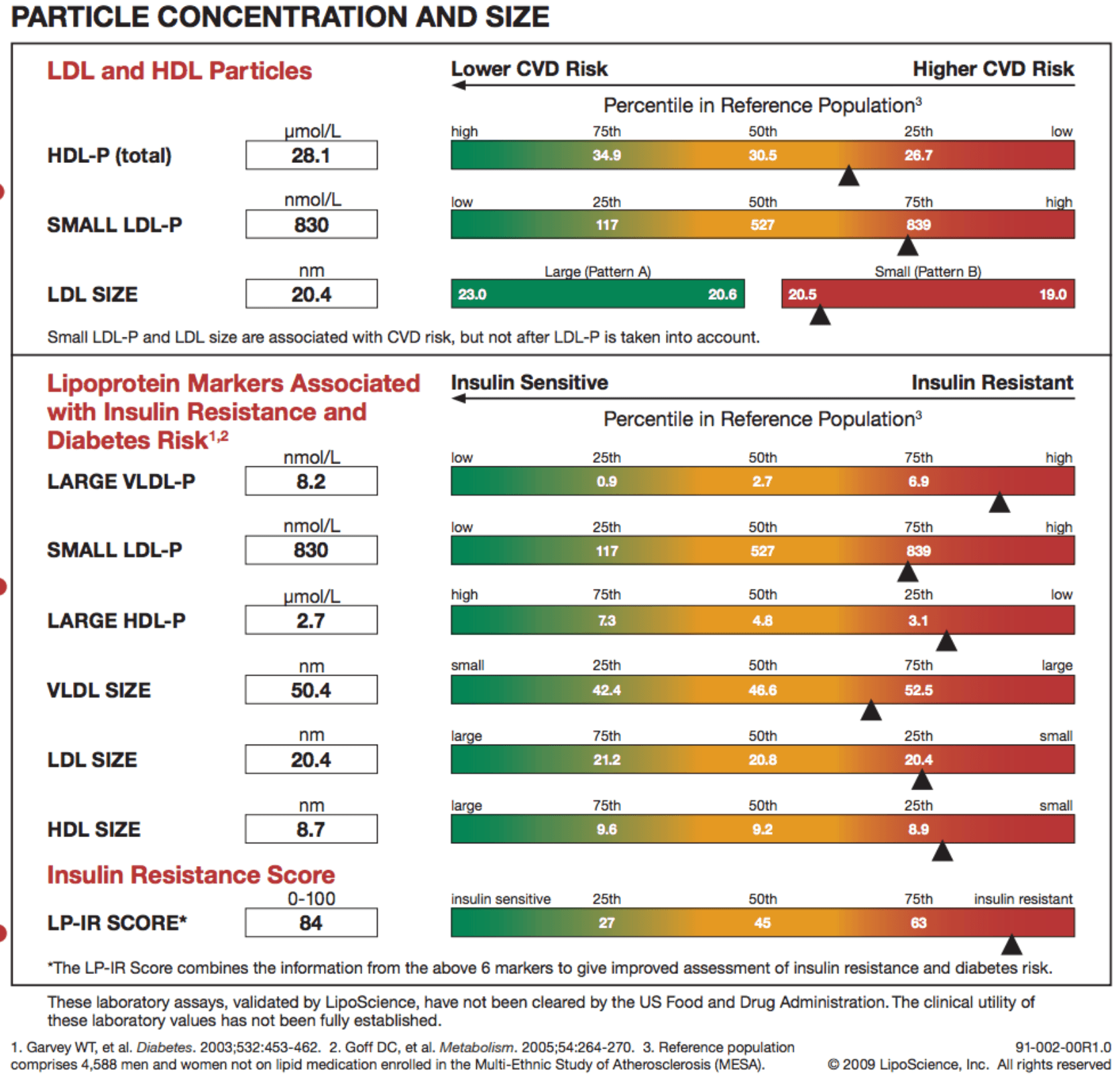

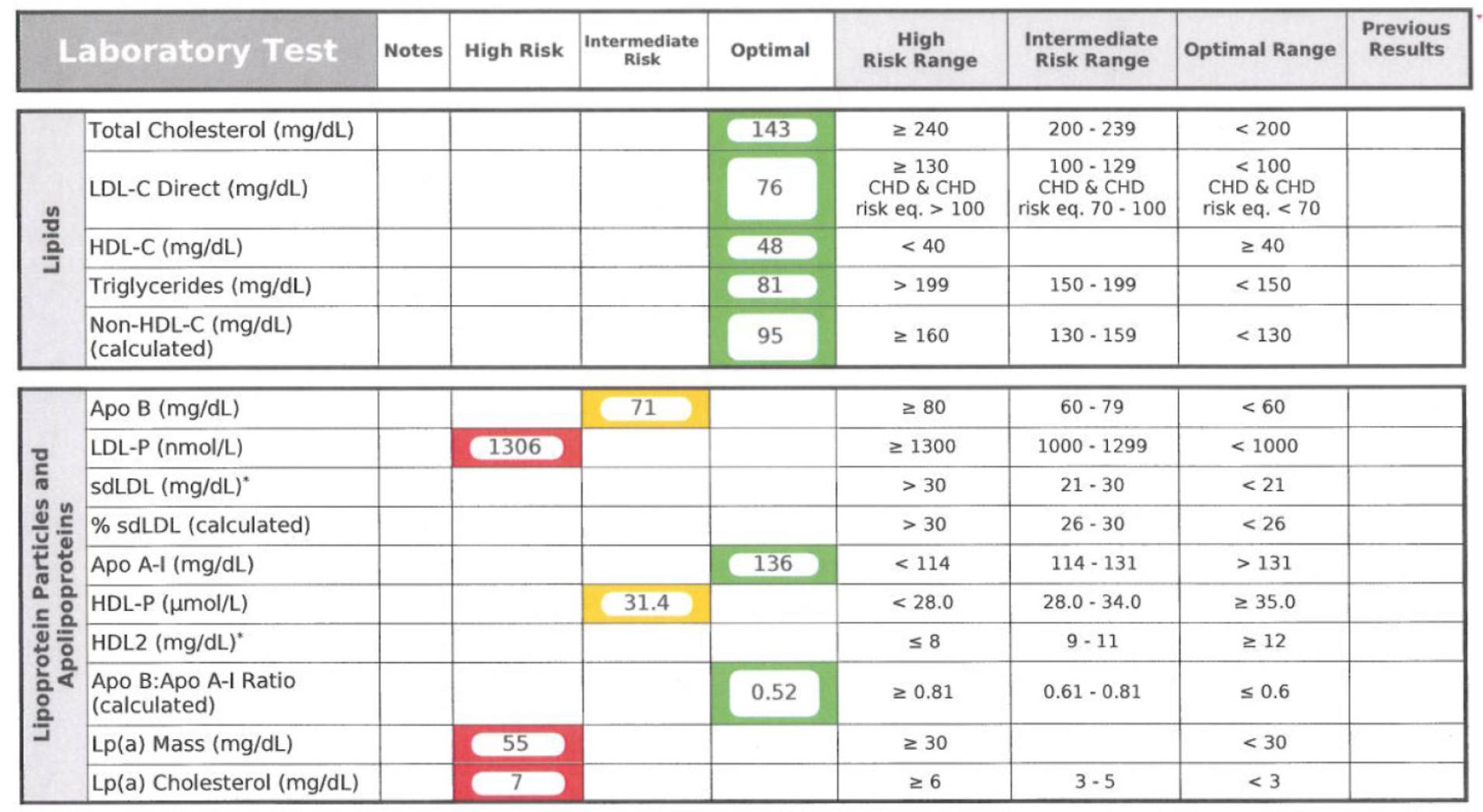

Below is a snapshot of how NMR reporting looks. This particular report is from Health Diagnostics Laboratory (HDL), Inc. LipoScience performs the actual NMR test, but HDL, Inc. runs a number of complimentary biomarkers I will discuss in subsequent posts. I now use the HDL, Inc. [now (circa 2017) True Health Diagnostics] test exclusively for reasons I will explain later.

In addition to counting the actual total number of LDL particles (LDL-P) and HDL particles (HDL-P) per liter, HDL, Inc. (not LipoScience) directly measures apoB and apoA-I. Furthermore, the size of each particle is measured using NMR in nanometers (to give you a sense of how small these things are, and why we need to use nanometers to measure them, about 1.3 million LDL particles stacked side-by-side would measure only one inch).

The final point I’ll make about the value of NMR reported subparticle sizes and diameters is particularly telling when it comes to insulin resistance. In the panel below, you can see that this person has small VLDL particles, small HDL particles, and LDL particles. Why is this interesting? The presence of increased large VLDL-P, large VLDL size, increased small LDL- P, small LDL size, reduced large HDL-P, small HDL size are early markers for insulin resistance, and such findings may actually precede more conventional signs of insulin resistance (insulin levels, glycemic abnormalities) by several years. In other words, the number and size of the lipoprotein particles is perhaps the earliest warning sign for insulin resistance.

In summary

- The measurement of cholesterol has undergone a dramatic evolution over the past 70 years with technology at the heart of the advance.

- Currently, most people in the United States (and the world for that matter) undergo a “standard” lipid panel which only directly measures TC, TG, and HDL-C. LDL-C can be measured directly, but is most often estimated.

- More advanced cholesterol measuring tests do exist to directly measure LDL-C (though none are standardized), along with the cholesterol content of other lipoproteins (e.g., VLDL, IDL) or lipoprotein subparticles.

- The most frequently used and guideline recommended test that can count the number of particles is the NMR LipoProfile. In addition to counting the number of particles – the most important predictor of risk – NMR can also measure the size of each lipoprotein particle, which is valuable for predicting insulin resistance in drug naïve patients, before changes are noted in glucose or insulin levels.

I know some of you are getting antsy. I thank you for your patience, and I hope you appreciate that it was a necessary step to get through this somewhat technical material and nomenclature. Next week we’ll get to the “fun” stuff – what does all of this cholesterol have to do with heart disease?

In addition, we’ll get further into the importance of using LDL-P as the best predictor of risk. If anyone wants to read up on another very important topic, especially for understanding why LDL-P is more important to know than LDL-C, get familiar with the concepts of discordant and concordant variables. You’ll be hearing a lot about these.

Photo by Fleur Treurniet on Unsplash

Peter I’m getting blood drawn (for the 4th time) to get my LDL-P from LipoScience. The other 3 were lost, or something… My local lab sends the sample to Quest in California, who theoretically should send it on to LipoScience. How does the Health Diagnostics laboratory fit into the process if LipoScience is doing the scan? Again great stuff. Dave

I think your wife probably figured out a long time ago that you have an obsessive type personality and throw yourself into whatever your current passion is head first. Fortunately for you now, a lot of people are reading your blog – so you’ve got that going for you which is nice (Caddyshack reference).

Doctor, doctor, doctor, doctor, doctor, aaaaaaand doctor! Did I miss anyone? (Spies Like Us reference).

HDL, Inc. sends blood to LipoScience specifically for the NMR. They do a large number of other tests that compliment the NMR.

Comment: I am a post-bypass 71 year old. My 15 year old by-pass arteries are doing fine, however, the desending posterior coronary is too pluged to receive a stent !

I am working hard at the low carb protocol as explained by yourself (for 6 months now) & weight is coming off but with heavy fat ingestion, I am concerned about causing more blockage; should I be concerned ?

Check NMR and inflammatory markers. Ask you doctor to get the full panel through HDL, Inc.

Damn! When the site was down today, I “sensed” that the next installment was coming. The F5 key on my keygboard is broken now.

One of the thing I find a little concerning about the tests is that they contain the predictive information of the moment – the same sort of information that makes doctors prescribe statins from the standard tests. They see somewhat elevated LDL-C and they want to write a scrip – it doesn’t matter that HDL is higher and triglycerides are low.

In short, I wish they would just report the numbers.

But thank you for another awesome post – I’ll read it again tomorrow (have pity on your East coast readers).

Note to self – always compose in Word which spellchecks and allows editing before posting.

This will take awhile to digest. Incredible work – thank you!

Have you seen the press release about Frank Sacks’ HDL study looking at apoC-III? https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2012/05/when-good-cholesterol-goes-bad/

How does that figure into this analysis?

These analyses are interesting, but difficult to draw firm conclusions from. They are often observational, not experimental. However, it does suggest how primitive our understanding remains. We know too many LDL-P are bad, but we still don’t really understand how it all fits together. Another caveat: no drug that has been designed to raise HDL-C (to date) has shown any efficacy in reducing heart disease. Interesting, huh?

Hi, thank you for a most insightful site. I don’t think Americans are stuck with the problem some of us here in South Africa have (caucasian Afrikaners and some Jews too) – we have familial hypercholesterolaemia. So now where does this throw us into the equation? I do know for certain that if children are born with a double gene from both mom and dad they are in very serious trouble. Our levels are always double digit. In metric it’s about 11 to 13 without medication. BUT then my mom who only found out about this in her 60’s has recently turned 80!!! And from her 60’s she was on and off meds. She didn’t like the idea. Yet still? It does frighten me however. My 2 sons also have this. The meds also never bring it down to acceptable levels. I have now gone on low carb diet just to see if it makes a difference. What is your opinion please. No-one thus far has answered me on this. Would so appreciate. Cheers

“no drug that has been designed to raise HDL-C (to date) has shown any efficacy in reducing heart disease. Interesting, huh?”

This is actually interesting… might this imply that other interventions (lifestyle, high levels of saturated fat, especially high intake of lauric acid… coconut oil) wouldn’t work either?

Which is interesting… if you are managing the numbers that are the inputs for “risk”… are you really changing your risk or changing your numbers?

To the extent you are not modulating causal factors, but biomarkers, then you probably arent modulating risk. Dont put out fires by hiding the smoke.

Not necessarily. It’s more likely to suggest that the rise in concentration of HDL-C is symptom of the positive metabolic change. Give a drug that only raises HDL-C –> no change in underlying metabolic problem. Fix HDL-C with “lifestyle” –> you fix a lot of other stuff with it.

Now it’s getting interesting! I had a chat with my sister (a physician). Surprisingly she understood right off the truth of how a low carb diet would be expected to affect the lipid profile, and she practically wanted to give me a VAP panel on the spot — but she’d never heard of the NMR.

Never too late to learn! I didn’t know about NMR until a year ago.

What is the NMR price?

Thanks. 🙂

Cost of NMR is probably under $100.

NMR lipoprofile from LabCorp November 2014 = $100

After LabCorp acquires LipoScience

NMR lipoprofile from LabCorp February 2015 = $150

50% increase, must have been an expensive acquisition.

Thanks again for the great posts. Can you give us any info on the relative costs for these tests? I’m going to guess that my health insurance will not cover the NMR test.

I’m not sure of the exact relative differences. Obviously a simple lipid profile is the cheapest. All of these tests probably cost under $100. The most deluxe of these panels, with advanced genotyping, can be done for $500. If an NMR is warranted, insurance almost always picks up the cost.

$127 at DirectLabs.com https://www.directlabs.com/OrderTests/tabid/55/language/en-US/Default.aspx (search NMR).

BTW- last year, Blue Shield in California denied coverage of my VAP panel as well as my hsCRP tests, because “these treatments weren’t supported by peer reviewed research”. I received a form letter to this effect and got so mad I dug up some research (NEMJ) and tried to get on the phone with them. But you know, I went through 60min of automated response systems before it transferred me to a number that was busy. I just gave up.

Thank you for the explanation of VAT. I was unaware that it was an estimate.

I couldn’t help but thinking as I read this post of the enormous impact of whatever the current state of technology has been on public health. We had the ability to measure total cholesterol and then we had Ancel Keyes and the Food Pyramid. We had the ability to fraction cholesterol and then we had “good cholesterol”/”bad cholesterol”. The whiz-bang of the day drives health policy and food policy, people try and do the right thing, and diabetes and heart disease marches on. Uncharacteristic of me as a lover of whiz-bang, this post has me feeling a tone of cautiousness that we need to be really careful this time, and we need to be very sober about understanding as much of the mechanisms as possible because a lot is riding on it.

I certainly need to do much more reading. My biggest question at this point is why are increasing particle number considered to be an early predictor of IR? Additionally, I get the metaphor of the increasing traffic in the artery [it’s the cars not the passengers] that’s more likely to cause an injury to the epithelium, but to me that sounds like “plaque clogging cholesterol”. What’s the mechanism that causes increased particle number and the mechanism that increases the risk of injury as a result of increased particle number? Asking these questions not so much for you to answer them, Peter, although if they come up in following posts that’ll be great, but rather just to try and sort out in my own head the things that I need to further hunt down. And yeah, that feeling of caution.

edit: Above, I meant “artery clogging plaque”.

Very informative: I hope you will cover why some of us generate more LDL particles for a given level of LDL than you would think. Is it just genetics; and if so what is the genetic basis for particle production? Are drugs the only way to deal with it? In my case, diet manipulation after learning I generated tons of particles was unsuccessful- still no matter the diet generated tons of particles with size differing- larger with less carbs. Particle count per last NMR was 569, but achievable only via Crestor 10 and Zetia 10.

Your wife has a great sense of humor! I love the T-shirt! May have to get some made- w/o the PA at the end of course!. Thanks for the hard,very important work; many will be benefited from it.

Genetics and diet play a large role in the discordance of LDL-P and LDL-C, which I’ll discuss subsequently.

So, if I go to my primary care physician for a check-up and he orders blood testing, can I request the NMR testing? Also, if he can do this, will insurance cover this?

Yes, and probably. Of course, your doctor needs to explain to them why this test is necessary. I’ve very rarely seen any issue with this.

I’m looking forward to reading your post on genetics and diet and LDL-P and LDL-C.

Thank you thank you for doing this! What you have written is going to be extremely helpful to me and other health educators. There is SO much misinformation out there in the general public (and in the minds of most medical practitioners for that matter) about cholesterol, heart disease, and diet. Your articles are going a long way to refute the “high cholesterol, take a Statin, continue to eat crap and get sicker” mind set that I encounter every day.

I think I’m getting to know enough about cholesterol to become an annoyance to my physician (and perhaps a hazard to myself…). Thanks for that, Dr. Attia. I kept wondering what you consider to be a “too terribly insulin resistant person”. Could I be one of those (I’ve been in ketosis for 3 months, strictly doing the induction phase of Atkins, and yet my HOMA-IR stubbornly remains at 2.4)? What should such a person do differently when monitoring lipids?

It’s possible.

If someone starts a low carb diet, a significant fall in TG should be expected, right? If the LDL-C ~ TC – HDL-C – TG/5 formula is then applied to estimate the dieter’s LDL-C before and during the diet, is it right to conclude then that the result during the diet will necessarily be higher than before the diet, only because TG has fallen? Looking at my own standard cholesterol tests before and during my diet, it seems this was exactly the case, which renders the slight increase I have verified in my LDL-C completely meaningless, doesn’t it???…

Not always. HDL-C often rises, too. The point, however, is that is probably doesn’t matter what’s happening to LDL-C. All that matters is what’s happening to LDL-P. Even the TG/HDL-C ratio becomes unimportant once you know LDL-P or possibly (real) apoB.

It is wonderful to read real information on this subject rather than the usual hysterical arm-waving. But knowledge always begets more questions. I hope you address these other questions: 1) Why does the body raise the LDL-C concentration? 2) When that happens, what is it telling us, assuming that it is doing so in response to some pathological or other condition that needs LDL for correction? It would seem that the body is sending a message, and we need to know how to interpret the message. Thank you for making the effort to write this clear series. I am very grateful.

My ideal TG/HDL ratio from standard LP could be misleading as I could still have excessive LDL-P particles, even if they are mostly pattern A. Previously I was skeptical about NMR. No longer.

A direct count from NMR makes sense. Inferences, like the formulaic calculation of LDL-C in standard LP, provide a range at best. Accuracy trumps inferences.

Thanks much for the education.

Thank you Peter. Almost everyone I know is trying to lower cholesterol with drugs and/or diet but the cardiologists are still very busy. Our friend had a very low cholesterol. His doctor said he would never have a heart attack. He had a heart attack. He is now on Lipitor. His very low cholesterol number didn’t prevent his heart problem. I think Vitamin C deficiency has something to do with this. Thank you again Peter.

Not uncommon to see LDL-C in the “low” range with sky-high LDL-P. Will discuss later.

Interesting article, I was wondering if you had any disclosure statements or conflicts of interest with these companies?

Great question, Eugene. Thank you for asking. I have no financial interest in any of these companies, nor do I receive any compensation in any form from any of them. As a provider, I now only use Health Diagnostics Laboratory, Inc. for any client (or friend or family member) I get bloodwork on. This choice is based on my belief in their comprehensive assays and the quality of their service.

Peter,

Thanks for all this important (but heavy) information.

My MD currently uses Berkerley HeartLab(BHL) for advanced lipid panels. How does the BHL “Segmented Gradient Gel Electrophoresis” (S-GGE) process fit with your recommendations? BHL says that it “is the only commercial standard method that correlates with” analytic ultracentrifugation (AnUc) which BHL cites as the “gold standard” for lipid fractionation (page 3 of BHL’s Clinical Implications Reference Manual https://www.bhlinc.com/pdf/CIRM_v1_2.pdf ). I do note that the cites in support of this statement are quite old!

I touch on this part II. There is only FDA-approved way to counter particles — NMR by Liposcience.

Thanks for the comprehensive explanation! I am not sure if this is the best place to ask this but here goes. Based on what I read here I have been using super starch and I love it. My question is should I count the 31 gr of carb toward the 50 gr max to get into ketosis or not. I only use the super starch when running, biking or swimming an hour or more. Thanks and I always look forward to your next post.

It’s not really clear. Probably not the whole amount, and it depends how much you’re exercising when you ingest it.

Speaking of this (and sorry, I also realize this is off topic of the lipid discussion), do you count fiber into your total CHO? (I’m assuming you’re not using any other “net carb” products).

I count ’em all. Certainly fiber has a lesser effect, but if I only need to keep track of one thing, this is easiest. The “high bar” so to speak.

I may be way off base for this comment but really, where is all this testing getting us? Is this what passes for preventive medicine these days? I thought preventive medicine was what we did BEFORE we had to go to the doctor. You know, eating right, getting lots of exercise, lots of fresh air and sunshine, reducing stress, staying slim, getting plenty of sleep, not working too hard – that kind of thing. Now we’re off to the doctor getting “check-ups” and “tests.” and Peter, you seem to be fostering all kinds of new more sophisticated tests, and telling us all about the ins and outs of even more intricate ways of finding out how complicated cholesterol really is.

I have not been to the doctor for a check up for 15 years and I don’t see the need to go. I’m not sick. I’m not fat. I don’t get flu shots. I don’t care if I have high cholesterol. I try to eat right. Now don’t flame me for this, but I see the sky high cost of the medical systems both in the US and in Canada as a result of people going to the doctor and having tests when they are not sick. If high cholesterol is not a worry for 90% of people why would anyone go for a check up and have a blood test for cholesterol?

Barbara, 4 weeks from now I’ll be exactly the same age as my father was when he dropped dead of a heart attack. I for one am VERY interested both in knowing all I can about such things as cholesterol (one component of which seems to be largely responsible for causing heart attacks); about recognizing and quantifying as well as possible my own risk of dropping dead; and of learning what if anything I can do to somewhat lessen the risk that I’ll drop dead next month.

Obviously, Peter here is providing some of that education; and he’s letting us know about new technology we can use to help identify and quantify those risks (and God knows we’ve been living in the dark ages using leeches up til this point); and he’s discussing dietary practices that may mitigate these problems. How is that not very relevant? You’r free not to care, but that being the case how do you wind up on this blog in the first place?

As for as the cost — yes I’m sure that we do a lot of needless screening and tests. But the solution is to develop and identify the RIGHT test to do, and not waste money administering a bunch of useless myth-based testing that leads to the obligatory useless prescription.

The data would suggest that preventative testing is not at the heart of what we spend on healthcare. Yes, the US spends more on healthcare than any other country by just about any metric you want to consider: total amount ($2.5 Trillion), %GDP (18%), per capita (about $8,000 per person per year). But here’s the thing…that money is not spent uniformly across one’s life. Most of the healthcare dollars a person spends are spent in the last 90 days of their life. It’s not the tests and check-ups that are killing our economy — it’s the catastrophic diseases we try to fight off when it’s probably too late.

We’re being decimated by 2 factors: 1) our behavior is driving an unhealthy lifestyle because poor infrastructure and poor information feed it; 2) and we only play “defense” — that is, we only spend money when it’s too late.

Is a $500 lab test worth it to let me know if I’m a ticking time bomb? It is to me. But you’ll have to make your own choice. Just make sure you’re starting with the right information, though.

Question to KevinF:

I found today a bottle of high oleic acid cold pressed safflower oil (organic), from Europe, but when I went to look at the breakdown of PUFA in it, it was all omega-6 (about 2.6g per tablespoon). Does that make any sense to you? Naturally, I didn’t buy it, as I do not wish to mess around with my OM6:OM3 ratio. You mentioned that high oleic acid cold pressed safflower oil should have very little if any PUFA of any kind in it, so the ratio hardly matters. But that does sound to me like alot of omega-6 – now perhaps I misread it (in Europe they use commas instead of decimal points), but I don’t think so! I believe it was 2,6g per tablespoon (15 mL). Does that seem like a huge amount to you?

Thanks in advance.

Dan

I see now I screwed up, Kevin. You said the ratio of MUFA:PUFA is 11:2, and that is exactly what’s in a Spectrum brand. The brand I saw was not spectrum and I do not recall the MUFA:PUFA ratio. I do think it had either 2.4 or 2.6 g of OM6 per tablespoon, which seems really high to me (if OM6 is as biologically active as OM3 – no idea).

That sounds about right Dan. I think I got the 11:2 ratio by noting that a tablespoon has 11 grams MUFA and 2 grams PUFA. And I suppose just about all that 2 grams PUFA is Omega 6. So yeah you probably get that much O6 in a tablespoon, and maybe they rounded down on the label. Nevertheless, hard to get much less than that if you to cook higher heat and avoid saturated fat (which I think was your original issue).

I’m thinking that’s not bad in terms of O6:O3 ratios, assuming 1) you are supplementing with a good Omega 3 or eating salmon, and 2) you are not using huge amounts of the oil. Not sure what your plans there are, but I’d be apt to use maybe a tablespoon in the wok doing a stir fry every now and then — can’t see me using a whole lot of it.

Aside from that kind of higher-heat application, you can stick with olive oil, which would have less Omega 6 (but still isn’t O6 free).

Barbara,

Information is power; why shy away from it?

Kevin, thanks so much for checking in and for writing me back and hope you will tolerate (I know you will) – two more questions

1) How is olive oil better? Is it just the lower OM6 content, or high resilience to heat? Or its use in the Mediterranean diet trial showing improved vascular outcomes (Lyon Heart Diet Study)?

2) 2+ grams per tbsp of OM6 still seems really high to me. If one wanted to maintain a 1:1 relationship of OM3:OM6, that would mean having to eat oily fish every day or popping a supplement (something I am really loath to do, for several reasons). Many of my stir-fry recipes call for well more than a tbsp (sometimes up to 3 tbsp), and a single serving of salmon or tuna would not provide sufficient OM3 coverage. Then again, I’m still very uncertain whether OM3:OM6 is simply an epiphenomenonal marker of “healthier” patterns of eating in general (for example, the very nice 1:1 ratios in Greenland and Japan have been correlated with better vascular health, but those are simply correlations not necessarily cause-and-effect relationships – we really need a randomized trial to dissect that).

Thanks again. It’s great to have such astute people to consult with.

Dan – Well keep in mind I don’t have a PhD in oil or anything, so I can just pass on what I’ve read. (A good book for example is called “The Queen of Fats”). I realize that a 1:1 ratio of O6:O3 is often said to be ideal, however I’m not sure how you get there in the real modern world. It’s hard to GET Omega 3, while it’s hard to AVOID Omega 6. There is some advice out there that a more achievable ratio of, say 4:1 in favor of Omega 6 is OK or at least an improvement — I think that’s now official advice in some countries. And really the typical America diet is probably somewhere between 15:1 and infinity to 1. (And now Peter is saying, just make sure you get your O3).

And you can drive yourself crazy looking up fat-sources in something like https://nutritiondata.self.com

… everything seems to have lots of Omega 6.

So my approach is to somewhat minimize the O6, while taking about 2.0 – 3.0 grams of liquid O3 supplement from Carlson Labs — citrus flavored, very nice, not fishy. I eat salmon when the opportunity presents itself but probably only once a week at most.

Olive oil is usually seen as good for two reasons: one, it’s nearly all MUFA and not PUFA or saturated fat. Some people fear saturated fat and some people fear PUFA, but just about everyone agrees mono is benign (at worst) or positively good for you. Even if it’s just benign, then this is a way to get some fat in your diet without megadosing on O6.

And then there is the Mediterranean diet theory — I won’t attempt to judge if that’s valid or not, but IF it’s valid there might be some mysterious X-factor that makes olive oil healthy, even beyond the whole MUFA/PUFA/SFA thing.

A drawback to olive is: yes it does have SOME omega 6. It does not have a good O6:O3 ratio. But the key is it doesn’t have much of either. So as far as oils go, it’s not a good source of Omega 3, but also it doesn’t deliver very much Omega 6, despite what the ratio looks like. But if you actually used a LOT of olive oil, yes the O6 will add up. Second drawback is, it has a lower smoke point than your PUFA type oils. It’s not a high-heat oil. So, not good for high-heat applications like true stir-fry.

So … to your case, you say you want to avoid saturated fat, I believe. But you also want to minimize O6. It’s hard to do both unless you just avoid added fats altogether. (And I don’t see how it’s possible on a true low-carb high-fat diet). It would be nice if there was a high-heat, O6-free, pure mono oil … but I’m not aware of any such thing. And you certainly are not supposed to be cooking with fish oil (it burns and becomes corrupted).

Finally one thing I’d recommend (at the risk of being obvious) is to use good modern non-stick pans. That way you don’t need much if any oil, unless you want want to add that fat on purpose, like I do with ghee or coconut. I’m sure I don’t use anywhere near more than a tablespoon of oil when I DO stir fry, in a pretty large wok. If you haven’t tried them, new white-surfaced ceramic pans are simply unbelievable. You could fry road tar in those things and wipe it off with a paper towel. Also, you can simply accept working at medium heat with olive instead of stir-frying at high heat.

Some of the bigger problems in modern medicine is the over diagnosis and overtreatment. You have it with PSA, mammography, cholesterol etc… Patients are being harmed more by the treatments than from the ailment they went to treat. Modern medicine is a business having patients to treat with pharmaceuticals and interventions is big business. You very be well informed before falling victims, there may be times were there could be more natural lifestyle modification and treatments available that you can try first.

Kevin, this is great and very helpful. Indeed I am trying to limit consumption of substances which might boost my LDL-P count. You are right that it is very difficult to both limit carbs and limit SFA and dietary cholesterol. It is like walking two tightropes rather than one.

Now on top of those two tightropes, imagine walking the OM6:OM3 ratio tightrope.

I am metabolically very sensitive to both carbohydrates and to fats, therefore I am attempting to maximize lean protein intake, coupled with MUFA and OM3 PUFA. Tricky to do, but my main sources of protein are now nuts, tofu, fish (both lean and oily), (skinless) chicken. Pretty much the Mediterranean diet (which unlike most diets has randomized trial evidence showing a reduction in hard outcomes). Fats for me will include olive oil and avocados (as well as, obviously, what’s in nuts and oily fish). I’ve cut out all red meat, butter, coconut oil, hard cheese, cream cheese, sour cream – the main chol/SFA sources in “low carb, high fat”.

I’m guessing for barbequeing (a truly high heat application – in many cases), you are applying ghee or coconut oil. I was actually applying olive oil, which I now see from your post is a very bad thing to do (as Peter once put it, bad to add heat to a double bond). This puts me in a bit of a quandry as I love to barbeque salmon and red snapper. The recipes I have seen even call for coating the fish with olive oil (before applying seasonings and prior to grilling on the ‘Q’). Is there anything other than SFA (coconut oil, ghee) that you would recommend for frying at high heat? I guess we come back now to high heat oleic acid containing safflower oil (cold-expressed)! Time for me to pick up some of that stuff!

Dan, Kevin, I’m planning to rock your paradigm a bit in the coming months with a series on n-6 and n-3. Hope you can wait until then.

Peter, I really look forward to it.

I just picked up a can of Spectrum organic high heat canola oil (expressed). Ingredients: Expeller Pressed Refined High Monounsaturate Canola Oil, Soy Lecithin, Propellant (no chlorofluorocarbons). This is the only thing I could find that said it was stable at the temps I barbeque at (400-425 F). The other choice was a cold-expressed organic safflower which did not promise heat stability and had 4.9 g of OM6 per teaspoon (10 mL). So given the devil of heat-produced free radicals and/or trans fats vs having to use canola with an unknown OM6 content but heat-stable, I chose the latter devil.

I love this site, as you can tell.

@Peter, I was just pointing here from Facebook, saying you tended to write in cliffhanger fashion. Are you sure you never worked in media?

@Dan, after all that, just an hour ago I think I found a winner for you. Was in a specialty grocer called Sprouts, and found a product called Napa Valley Naturals High-Oleic SUNflower oil. It has about the highest smoke point yet (460 degrees), and has only 1 gram PUFA per tablespoon, for a MUFA:PUFA ratio of 12:1. That there might be the best you can hope for.

It’s this product here, but not sure where you buy it if you don’t have Sprouts.

https://tracker.dailyburn.com/nutrition/napa_valley_naturals_organic_sunflower_oil_high_oleic_calories

My high heat cooking, such as I do it, is just wok and pan-frying. Sadly I haven’t lived in a grill-friendly place since I was out in Peter’s neck of the woods, living in Coronado.

Kevin, thanks for the tip. I am going to see if I can order this online.

I hit PubMed last night to see if pure saturated fat – in the form of coconut oil – and in the absence of dietary cholesterol – has any effect on serum lipid levels. There were about 7 or 8 direct feeding studies which suggested that coconut oil (which is high in myristic but also several other types of FAs) does increase apoB, total:HDL ratio, LDL, triglycerides and VLDL. Unfortunately none of them studied these in carbohydrate-restricted people; rather these were randomized, crossover trials in which all fat was from coconut oil (that would be a rare situation). Not surprisingly, Walter Willett has a piece in the Harvard Health Letter declaring caution regarding the burgeoning use of coconut oil. Lastly, none of these studies looked at LDL-P – I think that marker is just too new for major feeding trials to have pronounced any effect (though the changes in apoB are pretty telling).

Anyway, thanks for the tip re the sunflower oil!

DHackman, if you don’t mind me asking, how have you determined that you are sensitive to dietary fat? Thanks.