Want to catch up with other articles from this series?

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part I

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part II

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part III

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part IV

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part V

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part VI

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part VII

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part VIII

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part IX

Previously, across 8 parts of this series we’ve laid the groundwork to ask perhaps the most important question of all:

What should you eat to have the greatest chance of delaying the arrival of cardiovascular disease?

Before we get there, since this series has been longer and more detailed than any of us may have wanted, it is probably worth reviewing the summary points from the previous posts in this series (or you can just skip this and jump to the meat of this post).

What we’ve learned so far

- Cholesterol is “just” another fancy organic molecule in our body but with an interesting distinction: we eat it, we make it, we store it, and we excrete it – all in different amounts.

- The pool of cholesterol in our body is essential for life. No cholesterol = no life.

- Cholesterol exists in 2 forms – unesterified or “free” (UC) and esterified (CE) – and the form determines if we can absorb it or not, or store it or not (among other things).

- Much of the cholesterol we eat is in the form of CE. It is not absorbed and is excreted by our gut (i.e., leaves our body in stool). The reason this occurs is that CE not only has to be de-esterified, but it competes for absorption with the vastly larger amounts of UC supplied by the biliary route.

- Re-absorption of the cholesterol we synthesize in our body (i.e., endogenous produced cholesterol) is the dominant source of the cholesterol in our body. That is, most of the cholesterol in our body was made by our body.

- The process of regulating cholesterol is very complex and multifaceted with multiple layers of control. I’ve only touched on the absorption side, but the synthesis side is also complex and highly regulated. You will discover that synthesis and absorption are very interrelated.

- Eating cholesterol has very little impact on the cholesterol levels in your body. This is a fact, not my opinion. Anyone who tells you different is, at best, ignorant of this topic. At worst, they are a deliberate charlatan. Years ago the Canadian Guidelines removed the limitation of dietary cholesterol. The rest of the world, especially the United States, needs to catch up. To see an important reference on this topic, please look here.

- Cholesterol and triglycerides are not soluble in plasma (i.e., they can’t dissolve in water) and are therefore said to be hydrophobic.

- To be carried anywhere in our body, say from your liver to your coronary artery, they need to be carried by a special protein-wrapped transport vessel called a lipoprotein.

- As these “ships” called lipoproteins leave the liver they undergo a process of maturation where they shed much of their triglyceride “cargo” in the form of free fatty acid, and doing so makes them smaller and richer in cholesterol.

- Special proteins, apoproteins, play an important role in moving lipoproteins around the body and facilitating their interactions with other cells. The most important of these are the apoB class, residing on VLDL, IDL, and LDL particles, and the apoA-I class, residing for the most part on the HDL particles.

- Cholesterol transport in plasma occurs in both directions, from the liver and small intestine towards the periphery and back to the liver and small intestine (the “gut”).

- The major function of the apoB-containing particles is to traffic energy (triglycerides) to muscles and phospholipids to all cells. Their cholesterol is trafficked back to the liver. The apoA-I containing particles traffic cholesterol to steroidogenic tissues, adipocytes (a storage organ for cholesterol ester) and ultimately back to the liver, gut, or steroidogenic tissue.

- All lipoproteins are part of the human lipid transportation system and work harmoniously together to efficiently traffic lipids. As you are probably starting to appreciate, the trafficking pattern is highly complex and the lipoproteins constantly exchange their core and surface lipids.

- The measurement of cholesterol has undergone a dramatic evolution over the past 70 years with technology at the heart of the advance.

- Currently, most people in the United States (and the world for that matter) undergo a “standard” lipid panel, which only directly measures TC, TG, and HDL-C. LDL-C is measured or most often estimated.

- More advanced cholesterol measuring tests do exist to directly measure LDL-C (though none are standardized), along with the cholesterol content of other lipoproteins (e.g., VLDL, IDL) or lipoprotein subparticles.

- The most frequently used and guideline-recommended test that can count the number of LDL particles is either apolipoprotein B or LDL-P NMR, which is part of the NMR LipoProfile. NMR can also measure the size of LDL and other lipoprotein particles, which is valuable for predicting insulin resistance in drug naïve patients, before changes are noted in glucose or insulin levels.

- The progression from a completely normal artery to a “clogged” or atherosclerotic one follows a very clear path: an apoB containing particle gets past the endothelial layer into the subendothelial space, the particle and its cholesterol content is retained, immune cells arrive, an inflammatory response ensues “fixing” the apoB containing particles in place AND making more space for more of them.

- While inflammation plays a key role in this process, it’s the penetration of the endothelium and retention within the endothelium that drive the process.

- The most common apoB containing lipoprotein in this process is certainly the LDL particle. However, Lp(a) and apoB containing lipoproteins play a role also, especially in the insulin resistant person.

- If you want to stop atherosclerosis, you must lower the LDL particle number. Period.

- At first glance it would seem that patients with smaller LDL particles are at greater risk for atherosclerosis than patients with large LDL particles, all things equal.

- “A particle is a particle is a particle.” If you don’t know the number, you don’t know the risk.

- With respect to laboratory medicine, two markers that have a high correlation with a given outcome are concordant – they equally predict the same outcome. However, when the two tests do not correlate with each other they are said to be discordant.

- LDL-P (or apoB) is the best predictor of adverse cardiac events, which has been documented repeatedly in every major cardiovascular risk study.

- LDL-C is only a good predictor of adverse cardiac events when it is concordant with LDL-P; otherwise it is a poor predictor of risk.

- There is no way of determining which individual patient may have discordant LDL-C and LDL-P without measuring both markers.

- Discordance between LDL-C and LDL-P is even greater in populations with metabolic syndrome, including patients with diabetes. Given the ubiquity of these conditions in the U.S. population, and the special risk such patients carry for cardiovascular disease, it is difficult to justify use of LDL-C, HDL-C, and TG alone for risk stratification in all but the most select patients.

- To address this question, however, one must look at changes in cardiovascular events or direct markers of atherosclerosis (e.g., IMT) while holding LDL-P constant and then again holding LDL size constant. Only when you do this can you see that the relationship between size and event vanishes. The only thing that matters is the number of LDL particles – large, small, or mixed.

- HDL-C and HDL-P are not measuring the same thing, just as LDL-C and LDL-P are not.

- Secondary to the total HDL-P, all things equal it seems smaller HDL particles are more protective than large ones.

- As HDL-C levels rise, most often it is driven by a disproportionate rise in HDL size, not HDL-P.

- In the trials which were designed to prove that a drug that raised HDL-C would provide a reduction in cardiovascular events, no benefit occurred: estrogen studies (HERS, WHI), fibrate studies (FIELD, ACCORD), niacin studies, and CETP inhibition studies (dalcetrapib and torcetrapib). But, this says nothing of what happens when you raise HDL-P.

- Don’t believe the hype: HDL is important, and more HDL particles are better than few. But, raising HDL-C with a drug isn’t going to fix the problem. Making this even more complex is that HDL functionality is likely as important, or even more important, than HDL-P, but no such tests exist to “measure” this.

Did you say “delay?”

That’s right. The question posed above did not ask how one could “prevent” or eliminate the risk cardiovascular disease, it asked how one could “delay” it. There is a difference. To appreciate this distinction, it’s worth reading this recent publication by Allan Sniderman and colleagues. Allan sent me a copy of this paper ahead of publication a few months ago in response to a question I had posed to him over lunch one day. I asked,

“Allan, who has a greater 5-year risk for cardiovascular disease, a 25 year-old with a LDL-P/apoB in the 99th percentile or a 75-year-old with a LDL-P/apoB in the 5th percentile?”

The paper Allan wrote is noteworthy for at least 2 reasons:

- It’s an excellent reminder that age is a paramount risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

- It provides a much better (causal) model for atherosclerosis than the typical age-driven models, and explains why age is an important risk factor.

What do I mean by this? Most risk calculators (e.g., Framingham) take their inputs (e.g., age, gender, LDL-C, HDL-C, smoking, diabetes, blood pressure) and calculate a 10-year risk score. If you’ve ever played with these models you’ll quickly see that age drives risk more than any other input. But why? Is there something inherently “risky” about being older?

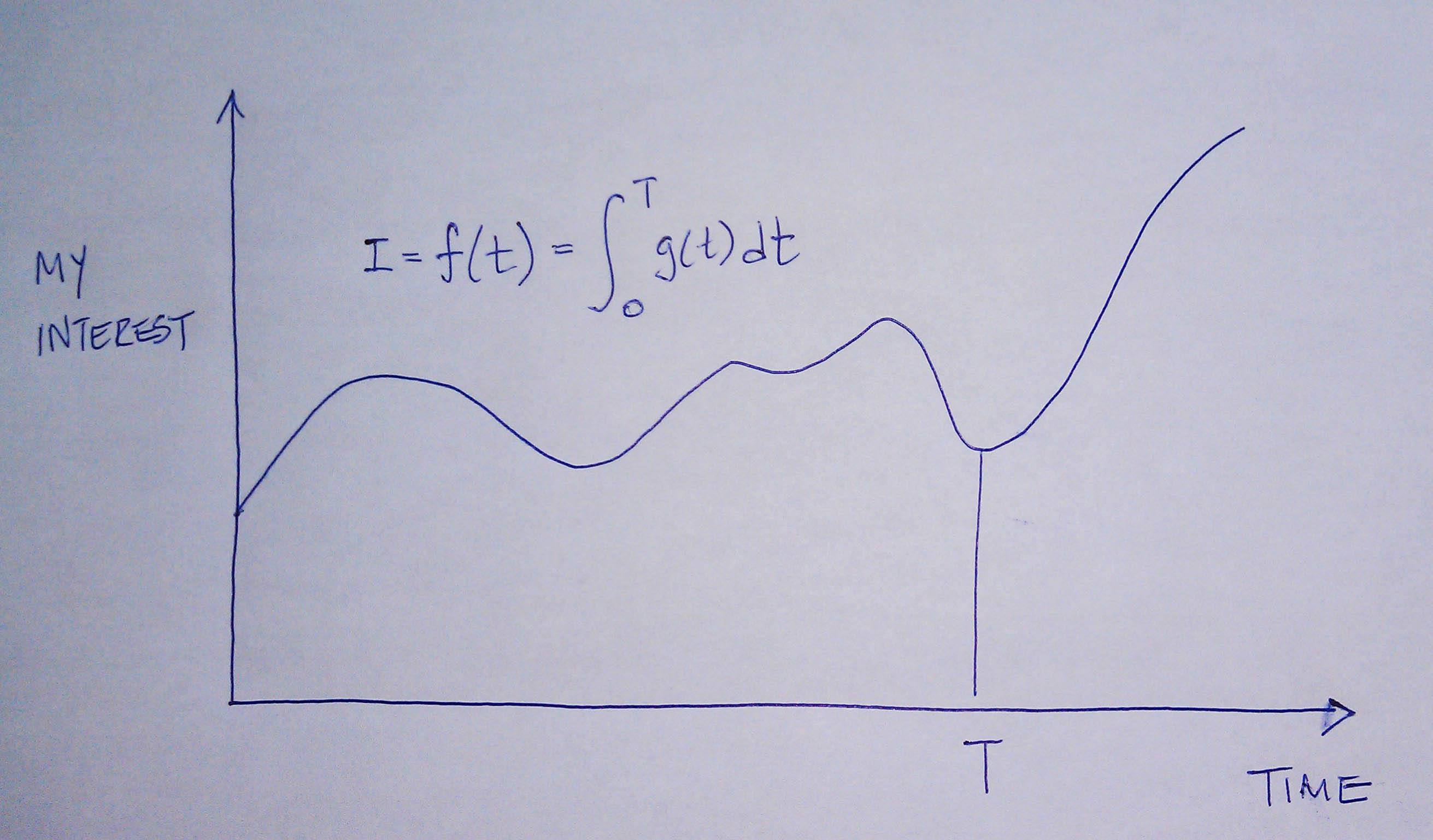

Sniderman and many others would argue (and I agree) that the reason age is a strong predictor of risk has to do with exposure to apoB particles — LDL, Lp(a), and apoB-carrying remnants. Maybe it’s because I’m a math geek, but such models just seem intuitive to me because I think of most things in life in terms of calculus, especially integrals, the “area under a curve.”

[I once tried to explain to a girlfriend who thought I wasn’t spending enough time with her that my interest in her should be thought of in terms of the area under the curve, rather than any single point in time. That is, think in terms of the integral function, not the point-in-time function. Needless to say, she broke up with me on the spot (in the middle of a parking lot!), despite me drawing a very cool picture illustrating the difference, which I’ve re-created, below.]

The reason age is such a big driver of risk is that the longer your artery walls are exposed to the insult of apoB particles, the more likely they are to be damaged, for all the reasons we covered in Part IV of this series. [This paper also reviews the clinical situation of PCSK9 mutations which builds a very compelling case for the causal model of apoB particles in the development of atherosclerosis].

What does eating have to do with cardiovascular risk?

So now that everyone is on the edge of their seat in anticipation of this punch-line, let me provide two important caveats.

First, there are no long-term studies – either in primary or secondary prevention – examining the exact question we all want to know the answer to with respect to the role of dietary intervention on cardiovascular disease. There are short-term studies, some of which I will highlight, which look at proxies for cardiovascular disease, but all of the long-term studies (looking at secondary prevention), are either drug studies or multiple intervention studies (e.g., cholesterol-lowering drug(s) + blood pressure reducing drug(s) + dietary intervention + exercise + …).

In other words, the “dream” study has not been done and won’t be done for a long time. The “dream” study would follow 2 randomized groups for many years and only make one change between the groups. Group 1 would consume a standard American diet and group 2 would consume a very-low carbohydrate diet. Furthermore, compliance within each group would be excellent (many ways to ensure this, but none of them are inexpensive – part of why this has not been done) and the study would be powered to detect “hard outcomes” (e.g., death), instead of just “soft outcomes” (e.g., changes in apoB, LDL-C, LDL-P, TG).

Second, everything we have learned to date on the risk relationship between cardiovascular disease and risk markers is predicated on the assumption that a risk maker of level X in a person on diet A is the same as it would be for a person on diet B.

Since virtually all of the thousands of subjects who have made up the dozens of studies that form the basis for our understanding on this topic were consuming some variant of the “standard American diet” (i.e., high-carb), it is quite possible that what we know about risk stratification is that this population is not entirely fit for extrapolation to a population on a radically different diet (e.g., a very-low carbohydrate diet or a ketogenic diet). Many of you have asked about this, and my comments have always been the same. It is entirely plausible that an elevated level of LDL-P or apoB in someone consuming a high-carb diet portends a greater risk than someone on a ketogenic or low-carb diet. There are many reasons why this might be the case, and there are many folks who have made compelling arguments for this hypothesis.

But we can’t forget the words of Thomas Henry Huxley, who said, “The great tragedy of science is the slaying of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact.” Science is full of beautiful hypothesis slayed by ugly facts. Only time will tell if this hypothesis ends up in that same graveyard, or changes the way we think about lipoproteins and atherosclerosis.

The role of sugar in cardiovascular disease

Let’s start with what we know, then fill in the connections, with the goal of creating an eating strategy for those most interested in delaying the onset of cardiovascular disease.

There are several short-term studies that have carefully examined the impact of sugar, specifically, on cardiovascular risk markers. Let’s examine one of them closely. In 2011 Peter Havel and colleagues published a study titled Consumption of fructose and HFCS increases postprandial triglycerides, LDL-C, and apoB in young men and women. If you don’t have access to this journal, you can read the study here in pre-publication form. This was a randomized trial with 3 parallel arms (no cross-over). The 3 groups consumed an isocaloric diet (to individual baseline characteristics) consisting of 55% carbohydrate, 15% protein, and 30% fat. The difference between the 3 groups was in the form of their carbohydrates.

Group 1: received 25% of their total energy in the form of glucose

Group 2: received 25% of their total energy in the form of fructose

Group 3: received 25% of their total energy in the form of high fructose corn syrup (55% fructose, 45% glucose)

The intervention was relatively short, consisting of both an inpatient and outpatient period, and is described in the methodology section.

Keep in mind, 25% of total energy in the form of sugar is not as extreme as you might think. For a person consuming 2,400 kcal/day this amounts to about 120 pounds/year of sugar, which is slightly below the average consumption of annual sugar in the United States. In that sense, the subjects in Group 3 can be viewed as the “control” for the U.S. population, and Group 1 can be viewed as an intervention group for what happens when you do nothing more in your diet than remove sugar, which was the first dietary intervention I made in 2009.

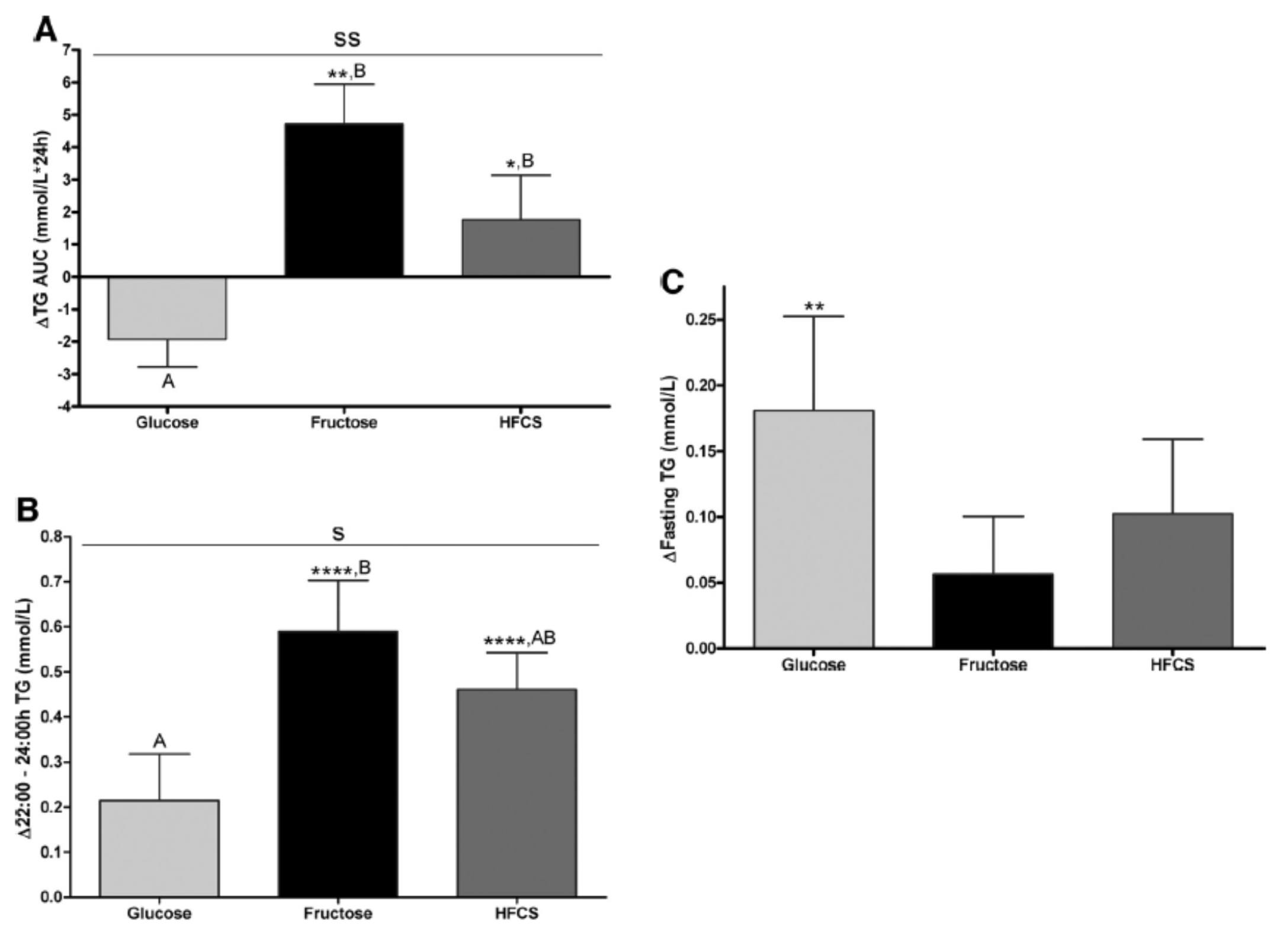

Despite the short duration of this study and the relatively small number of subjects (16 per group), the differences brought on by the interventions were significant. The figure below shows the changes in serum triglycerides via 3 different ways of measuring them. Figure A shows the difference in 24-hour total levels (i.e., the area under the curve for serial measurements – hey, there’s our integral function again!). Figure B shows late evening (post-prandial) differences. Figure C shows the overall change in fasting triglyceride level from baseline (where sugar intake was limited for 2 weeks and carbohydrate consumption consisted only of complex carbohydrates).

The differences were striking. The group that had all fructose and HFCS removed from their diet, despite still ingesting 55% of their total intake in the form of non-sugar carbohydrates, experienced a decline in total TG (Figure A, which represents the daily integral of plasma TG levels, or AUC). However, that same group experienced the greatest increase in fasting TG levels (Figure C). Post-prandial TG levels were elevated in all groups, but significantly higher in the fructose and HFCS groups (Figure B). The question this begs, of course, is which of these measurements is most predictive of risk?

Historically, fasting levels of TG are used as the basis of risk profiling (Figure C), and according to this metric glucose consumption appears even worse than fructose or HFCS. However, recent evidence suggests that post-prandial levels of TG (Figure B) are a more accurate way to assess atherosclerotic risk, as seen here, here, and here. One question I have is why did the AUC calculations in Figure A show a reduction in plasma TG level for the glucose group?

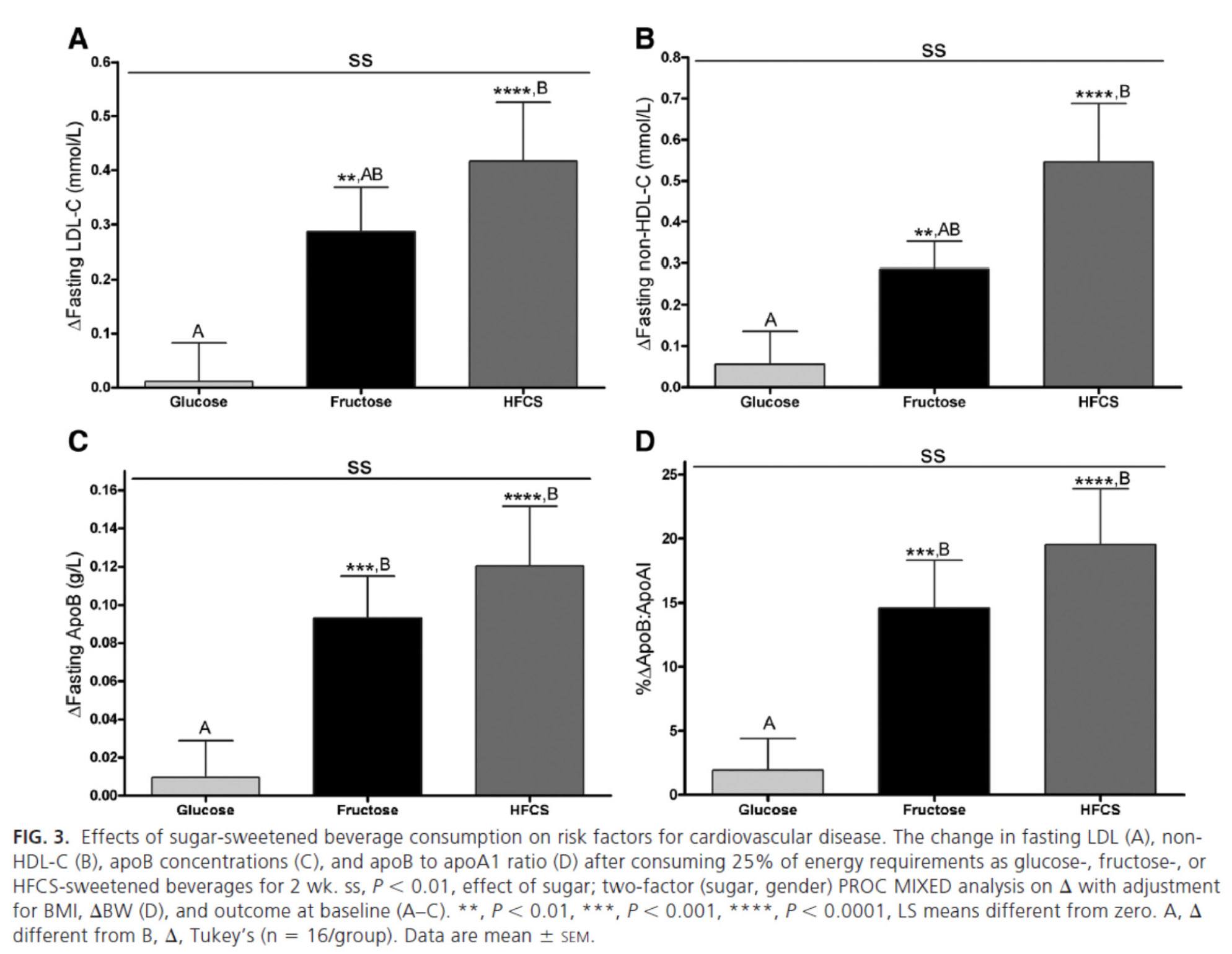

The figure below summarizes the differences in LDL-C, non-HDL-C, apoB, and apoB/apoA-I.

Again, the results were unmistakable with respect to the impact of fructose and HFCS on lipoproteins, and by extension, the relative lack of harm brought on by glucose in isolation. [Of course, removal of glucose and fructose/HFCS would have been a very interesting control group.]

One of the simultaneous strengths and weaknesses of this study was the heterogeneity of its subjects, who ranged in BMI from 18 to 35, in age from18 to 40, and in gender. While this provided at least one interesting example of age-related differences in carbohydrate metabolism (older subjects had a greater increase in triglycerides in response to glucose than younger subjects), it may have actually diluted the results. There were also significant differences between genders in the glucose group.

What was most interesting about this study was the clear difference between the 3 groups that was not solely a function of fructose load. In other words, the best outcome from a disease risk standpoint was in the glucose group, while the worst outcome was not in the all-fructose group, but in the 50/50 (technically 55/45) mixed group. This is a very powerful indication that while glucose and fructose alone can be deleterious in excess, their combination seems synergistically bad.

The role of saturated fat in cardiovascular disease

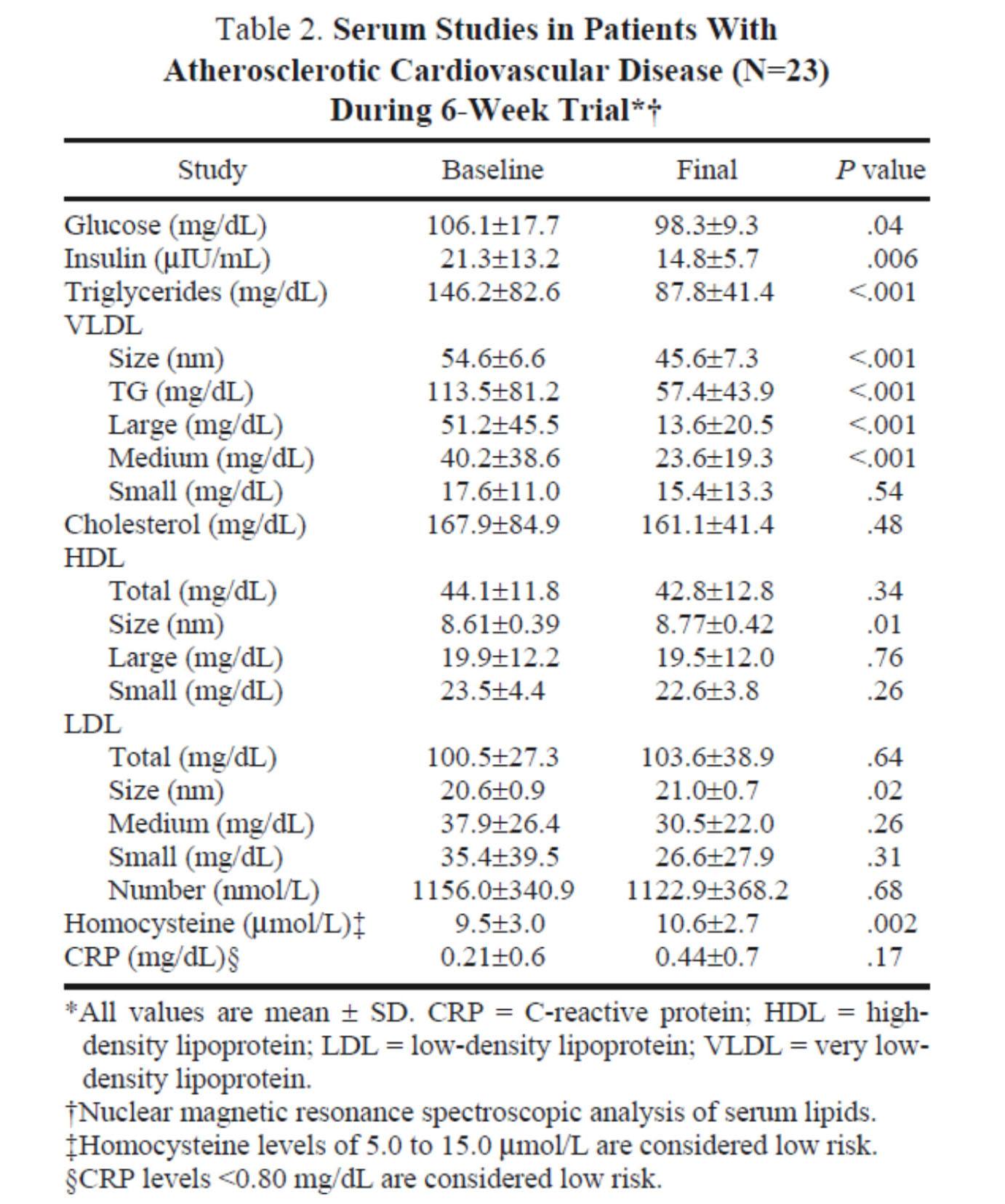

In the next week or two I’ll be posting an hour-long comprehensive lecture I gave at UCSD a few weeks ago on this exact topic. Rather than repeat any of it here, I’ll highlight one study that I did not include in that lecture. The study, Effect of a high saturated fat and no-starch diet on serum lipid subfractions in patients with documented atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, published in 2003, treated 23 obese patients (average BMI 39) with known cardiovascular disease (status post coronary artery bypass surgery and/or stent placement) with a high-fat ketogenic diet. Because the study was free-living and relied on self-reporting, not all subjects had documented levels of elevated serum B-OHB. However, the subjects were instructed to avoid starch and consume 50% of their caloric intake via saturated fat, primarily in the form of red meat and cheese. There were no restrictions on fruits and vegetables, which may have accounted for the observation that not all subjects were ketotic during the 6-week intervention. In total, only 5 of the 23 patients achieved documented ketosis.

All of the subjects were on statins and entered the study at a goal LDL-C level target of 100 mg/dL, which may have been the only way the authors could get the IRB to approve such a study.

The table below shows the changes in lipoprotein fractions following the intervention (there was no control group):

This study was conducted during the height of the “outcry” over the Atkins diet. While most doctors reluctantly agreed that Dr. Atkins’ diet could reduce body fat, most believed it was still very dangerous. In the words of Dean Ornish, “Sure you can lose weight on a low-carb diet, but you can also lose weight on heroin and no one would recommend that!”

Fair point. In fact, the authors of this study acknowledged that they “strongly expected” this dietary intervention to increase risk for cardiovascular disease, which is why they only included subjects on statins with low LDL-C. However, as you can see from the table above, the authors were startled by the results. The subjects experienced a significant reduction in plasma triglycerides and VLDL triglycerides, without an increase in LDL-C or LDL-P. In fact, LDL size and HDL size increased and VLDL size decreased – all signs of improved insulin resistance. Furthermore, fasting glucose and insulin levels also decreased significantly. The mean HOMA-IR was reduced from 5.6 to 3.6 (normal is 1.0) and TG/HDL-C from 3.3 to 2.0 (normal is considered below 3, but “ideal” is probably below 1.0) in just 6 weeks. Taken together, these changes, combined with the dramatic change in VLDL size, suggest insulin resistance was dramatically improved while consuming a diet of 50% saturated fat!

As all of these patients were taking statins, we’re really robbed of seeing the impact of this diet on LDL-P, which did not change. Also, CRP levels rose (though not clinically or statistically significantly).

Putting it all together

It is very difficult to make the case that when carbohydrates in general, and sugars in particular, are removed or greatly reduced in the diet, insulin resistance is not improved, even in the presence of high amounts of saturated fats. When insulin resistance improves (i.e., as we become more insulin sensitive), we are less likely to have the signs and symptoms of metabolic syndrome. As we meet fewer criteria of metabolic syndrome, our risk of not only heart disease, but also stroke, cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease goes down.

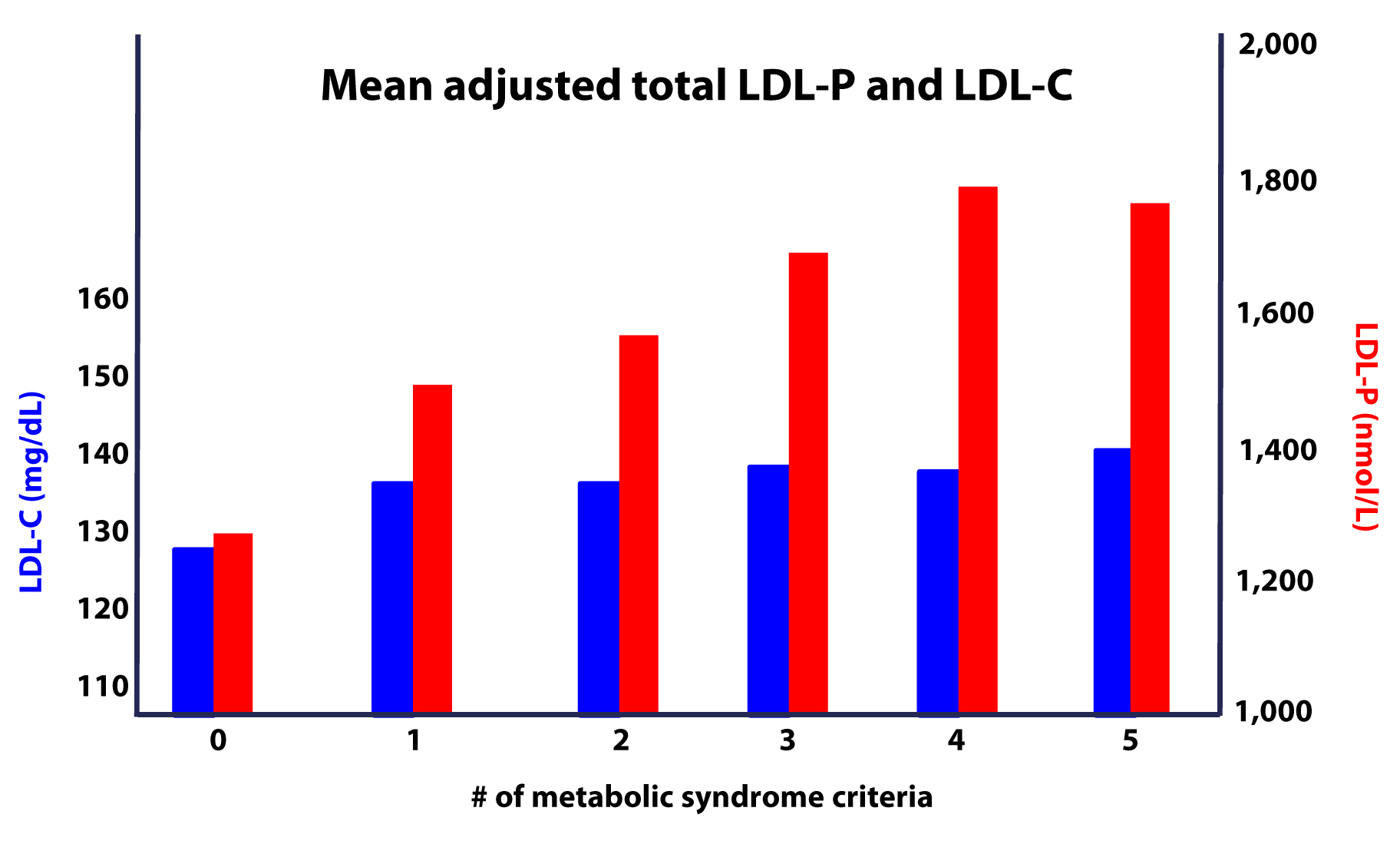

Furthermore, as this study on the Framingham cohort showed us, the more criteria you have along the spectrum of metabolic syndrome, the more difficult it becomes to predict your risk, due to a widening gap in discordant risk markers, as shown in this figure.

As I noted at the outset, the “dream” trial has not yet been done, though we (NuSI) plan to change that. Until then each of us has to make a decision several times every day about what we will and won’t put in our mouths. Much of this blog is dedicated to underscoring the impact of carbohydrate reduction on insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome.

The results of the trials to date, combined with a nuanced understanding of the lipoprotein physiology and their role on the atherosclerotic disease process, bring us to the following conclusions:

- The consumption of sugar (sucrose, high fructose corn syrup) increases plasma levels of triglycerides, VLDL and apoB, and reduces plasma levels of HDL-C and apoA-I.

- The removal of sugar reverses each of these.

- The consumption of fructose alone, though likely in dose-dependent fashion, has a similar, though perhaps less harmful, impact as that of fructose and glucose combined (i.e., sugar).

- The addition of fat, in the absence of sugar and starch, does not raise serum triglycerides or other biomarkers of cardiovascular disease.

- The higher the level of serum triglycerides, the greater the likelihood of discordance between LDL-C and LDL-P (and apoB).

- The greater the number (from 0 to 5) of inclusion criteria for metabolic syndrome, the greater the likelihood of discordance between LDL-C and LDL-P (and apoB).

I would like to address one additional topic in this series before wrapping it up – the role of pharmacologic intervention in the treatment and prevention of atherosclerotic disease, so please hold off on questions pertaining to this topic for now.

Peter there are many interesting papers on the “ancient pathway called autophagy”

Its activation is linked to starvation , Ketones , and vitamin D ( also papers looking at hibernation in animals )

My Question ( linked to the niacin question )

Is this .. –> It seems a lot known about the cholesterol question is only known as averages in a population suffering carbohydrate excess and vitamin D deficiency .

Probably such people have this “ancient pathway called autophagy” down regulated . ( “we don’t eat ourselves enough” ( papers suggest this is so and a cause of age related diseases ) .

How many other pathways might be effected .? ( previous question on Niacin )

Maybe many concerns on the cholesterol question become altered .

Maybe a Ketogenic diet and Vitamin D could reverse and prevent arteriosclerosis and that other things like autophagy become important than cholesterol numbers ?

I am reading the work of Thomas Seyfried on Cancer and I have a family member with Epilepsy doing much better on a ketogenic diet. I have adopted a Ketogenic diet myself.

The diet seems to change multiple systems in the body and has seen in epilepsy works through many pathways.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/09/110908124140.htm

Process That Clears Cholesterol Could Reverse Major Cause of Heart Attack

ScienceDaily (Sep. 9, 2011) — Researchers at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute (UOHI) have discovered that an ancient pathway called autophagy also mobilizes and exports cholesterol from cells.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/09/110908124140.htm

Coronary atherosclerosis: Significance of autophagic armour

“Autophagy is a lysosomal degradation pathway of cellular components such as organelles and long-lived proteins. Though a protective role for autophagy has been established in various patho-physiologic conditions such as cancer, neurodegeneration, aging and heart failure, a growing body of evidence now reveals a protective role for autophagy in atherosclerosis, mainly by removing oxidatively damaged organelles and proteins and also by promoting cholesterol egress from the lipid-laden cells. Recent studies by Razani et al and Liao et al unravel novel pathways that might be involved in autophagic protection and in this commentary we highlight the importance of autophagy in atherosclerosis in the light of these two recent papers.”

https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v4/i9/271.htm

Raymund, your point does speak to an issue I and others have raised. I don’t know the answer and can only speculate, which I’ve done. Curious as the thoughts of others, also. Thanks for compiling.

Just read the series after coming across the synopsis on Mark’s Daily Apple a few weeks back. Thanks for the effort and information. As someone trying to learn as much as possible for myself, my family, friends and clients, series like this are invaluable. Your analogies are very helpful in discussing these things and are a must have when interacting with people who have conventional wisdom filled brains and a little less biology in their backgrounds. I look forward to exploring your site in more detail. Thanks again!

Peter,

First off, I know you can’t give medical advice over the internet. I respect that. I am however at a bit of a loss. I did 3 months on a strict ketogenic diet (not one cheat day and all “clean” whole foods). I got my standard lipid profile and an NMR.

TC: 229

LDL-C: 169

HDL-C: 55

TG: 22

LDL-P: 2192

I was obviously happy with my TG and HDL (previous “healthy” diet HDL was 36). But my LDL-P number is concerning me.

Without asking for medical advice, is there something that could have effected the test to make that number so high? Was I not on the diet long enough? I’m definitely disappointed in that number. I’m hoping that maybe something went wrong somewhere and that’s not an accurate number. Anything you can tell me would be much appreciated but I understand and respect your limitations.

Brian

Brian, I am definitely going to be doing a post on this exact topic, so I hope you can hold tight till I get there. The short answer is this: I actually don’t know what to make of a high LDL-P in the presence of remarkable TG and HDL-C…but I’m working very hard with some of the country’s experts to sort this out. In the mean time, I could suggest folks in your situation consider non-invasive testing to further stratify risk, such as hs-CRP, Lp-PLA2, CIMT, MPO. I won’t leave you hanging, but I need a bit more time to aggregate information. There is a great post you might want to read that addresses this: https://azsunfm.blogspot.com/2012/09/font-definitions-font-face-font-family.html

Brian,

Hey, I just posted my numbers at the bottom. They are similar to yours, but LDL-P is actually worse than yours. I feel your pain. I don’t know what to make of it either.

I fall in the discordant group, too, that is mentioned here. Super wonderful “standard” tests including TG/HDL (<.5), eating strategy ketogenic (tested by meter), feel great, last NMR 2400+. Cartoid arteries clear of plaque. I was the one that told my doctor about NMR and they didn't resist to having it done. That was in May. Next one December. I continue to do what I have been doing and choosing not to worry. Looking happily toward the day when your post on this, Peter, appears. Thanks for all you do.

I listened to you on a few podcasts and wanted to get your opinion on my lab results.

I’m a 5’2″ 44 year old female who is pretty lean. I eat a low carb diet (probably not under 50, but under 75 – never calculated it). Here are my #’s

Total Chol 299

HLD-C 85

Trigs 50

LDL-P 1,981

LDL-C 204

HDL-P 41.6

Small LDL-P 173

LDL Size 21.4

My Insulin resistance score was 6

My doctor is insisting I go on a statin. Is my lipid profile dangerous that I would need a statin? I’m pretty sure they don’t show to help females at all, but he says I have familiar Hypercholestrolimia so that would need medication. Should I cut down on my saturated fat consumption? I consume coconut oil, MCT oil, coconut milk and coconut flakes and red meat daily. I have never been overweight and I strength train and am athletic. Do hormones affect your LDL? I just got lab work from an endocrinologist since I don’t seem to make any hormones and thought maybe the 2 were related since cholesterol makes hormones, maybe it’s a pituitary issue that’s driving my numbers up. Any insight to my concerns and confusion would be great. Thank you.

I’m sorry Cara, I can’t provide medical advice.

I have been holding my breath for part x, the one that probably interests a lot of people: the role of pharmacologic intervention.

It must not be easy to write about this. It’s one thing to describe and explain relatively objective facts, but not so simple to wade in the more controversial waters of medication use.

I am looking forward to your post on this.

Bernard, I sure do hope I can get to this, but there a few pressing issues ahead of it.

Peter,

You posted somewhere (and I can`t find) a multi-day recording of your NMR numbers and their variability which I believe was significant.

Where was this ?

Was your diet constant throughout ?

Thank You

I have not posted it yet, but I did allude to it in a post. Variability on LDL-P was over 10%, while apoB and LDL-C were less than 5%. Yes, diet constant through the 3 days.

Hi Peter,

I’ve only skimmed through most of this, but so far I’m impressed. Excellent work.

Disclaimer: I am not requesting medical advice, but rather a dietary compromise.

Here is my situation. After reading Gary Taubes “Why We Get Fat”, I switched to a high fat low carb diet, which I’ve faithfully adhered to for the past 4 months. When I started this diet I was about 185 lbs (I’m 5’8). After two months on the diet I dropped down to 168 lbs, which has been pretty much been maintained for the past two months.

Now I started this diet knowing I would have a physical coming up, and my wife has said “If your cholesterol goes up, this diet stops”.

Well, I had my physical last week and here were the results:

LDL = 170 mg/dl

HDL = 74 mg/dl

TG = 64 mg/dl

My PCP said my LDL jumped 80 points since my last physical (a year ago). For the sake of full disclosure, I’m on ramipril 5mg for hypertension, and I exercise infrequently (averaging 3 or 4 days every other week).

Anyway, once my wife finds out about my LDL, there’s going to be a “debate” about the future of my diet, and I’m wondering what sort of compromises I can offer that will keep me in ketogenic mode (honestly i feel great), but are friendly to the anti-saturated fat/anti-cholesterol group.

Here’s my typical diet:

Breakfast: 3 eggs, 3 or 4 slices of bacon, 3 sausage links, pretty much everyday

Lunch: chicken (thighs, legs), burgers (no bun), 4 or 5 servings of spring mix, sometimes fish.

Dinner: same as above (lunch is usually left overs)

snacks (salami, roast beef deli meat, deli cheese, polio string cheese, almonds, cashews)

Thanks in advance

Correction:

LDL = 179 mg/dl

TG = 54 mg/dl

TG/HDL ratio = 0.73

Thanks again.

This is a science question.

Cholesterol is used for steroid hormones synthesis. One such hormone is aldosterone, which is responsible for fluid and sodium retention. Now going backwards until I get to my point, aldosterone secretion is triggered by angiotensin II, which is converted from angiotensin I by angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), correct? Well, ramipril is an ACE inhibitor, so that entire process is interrupted. Less angiotensin I is converted to angiotensin II, meaning there is less available to trigger aldosterone secretion.

If less aldosterone is secreted, could that mean that less is synthesize? And if so, is it possible that the raw materials to produce the aldosterone are continuing to be supplied in spite of demand by the adrenal glands? And if so, could that account for the elevated LDL-C count?

Thanks.

I don’t think the production of aldosterone is significant enough to account for the difference you describe.

Peter,

Have read through this entire series, it was very well done, thank you. I have also tried to read through as many comments as I can to find an answer to my question but there are a lot throughout the series. My question is how you would suggest going about finding a primary care physician that is staying on top of the most current research and theories as you do. In my experience, most of the doctors I have had contact with seem to be a decade behind, and given this subject, that is too far. My family has always had issues with cholesterol and heart disease. My father has gone the route of avoiding cholesterol in food and using statins as suggested by his doctor (a very well known doctor in the media). He has been maintaining a decent total/LDL level for a while but I get the feeling his risks are not reduced, especially after your series. I myself have had good numbers but my ApoB level is elevated (not sure if it is an estimated or directly measured value) and want to get NMR testing as you have pointed out. In the end a doctor who can help me manage these numbers and figure out a way to reduce my risks using the most up to date (and credible) research out there instead of what they have learned 20 years ago. Any suggestions on how to find the right physician would be greatly appreciated.

Thanl

Ari, beyond the stuff you’ve already probably tried, I’m not sure I can offer much, other than to suggest you not rest until you find a doctor that meets your standards.

Hi Ari, have you looked into Jimmy Moore’s (livinglavidalowcarb) list of low-carb doctors?

Hi Ari and Peter,

There are a couple of websites that can be of potential help to you and others. Lipidboard.org and lipid.org have databases of members by area of the country. Some of these lipidologists are also cardiologists and primary care physicians. Best wishes, maryann

I’m still working through the material, so forgive me if this has already been answered.

On the first part you wrote “…Everything I have learned and continue to learn on this topic has been patiently taught to me by the words and writings of my mentors on this subject: Dr. Tom Dayspring, Dr. Tara Dall, Dr. Bill Cromwell, and Dr. James Otvos.”

What role did they actually play? Did you have a personal dialogue with them, or was this a condensation of their research and knowledge passed via other sources? Have any of these individuals reviewed this series of articles or commented on it?

Thank you for this excellent series, Peter. I hope to see lots more in the future.

All of the above.

Hi Peter, I am just trying to understand how much do Coconut/MCT oil “extend” Ketosis? Do they help you produce Ketones even if you go a bit more that 50g of carbs?

Also hypothetical question, if I am eating lets say 80g of carbs, I am probably not producing Ketones and therefore probably not getting enough glucose for the brain? So is it not healthy to be just above Ketosis?

Dr. Attia thank you for this excellent and educational series on cholesterol, and also to all those who have provided a valuable contribution with their questions and comments. I have one question which I would like to ask, it’s a point I’ve seen discussed on other forums but no one has been able to provide a proper answer:

It relates to a person who is following a low to very low carbohydrate paleo diet, has no obvious health problems, non smoker who looks after his/her health but with a family history of CVD. Following an NMR test the person finds out he/she has a LDL-P count of 3000 nmol/L, Trig/HDL-C = 0.75 (HDL-C77, LDL-C 220, Trig 57), Lp (a) 70, IR score of 25, hs-CRP 0.20, Lp-PLA 250, Apo E 3/4 . With such a high particle count what options does this person have? What should he/she be doing if a low carb / high fat diet has been followed for some time?

One should wait for part X of the cholesterol series.

Dr. Attia,

IMO you have written the most informative series on cholesterol I have seen. I am waiting for X hoping that the contents will answer a question that is very important to me. I recently had a drug-alluding stent placed through my 88% occluded circumflex artery. In addtion, my right coronary artery is 100% occluded but has found a collateral blood supply so that area of the heart is healthy according to cardiology. This stent requires drug therapy for about a year after placementt, so I must take Plavix for that period of time. As Plavix is used to prevent blood clotting, does it conflict with taking Vitamin K-2? Also, I have been on a high dose statin from 1988 until about 2 years ago when I stopped it after developing neuropathy in my feet and severe muscle pain in my legs and shoulders. I have acheived about the same cholesterol levels after about a year on low carb as I did with the statin,

while losing close to 40 pounds. I also participate in a very high level of excercise now that I’m angina free. I am very interested in seeing your view on drug therapy for lowering cholesterol. Lipitor will lower LDL but there may be a painful price to pay in the process. I fear that the truth is yet to be told about these drugs.

Dr. Attia

I greatly appreciate your efforts to educate us about nutrition and health. It is difficult for most folks to objectively evaluate often seemingly contradictory information on healthy eating. The following link to an article published in the Journal Circulation (2010) argues that dietary cholesterol from foods like egg yolks present a serious risk associated with increased vascular inflammation. Can you comment?

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2989358/

You realize Spence is the same guy who thinks eating eggs is as harmful as smoking in terms of vascular disease, right? Oh, and that’s all based on observational epidemiology.

Dr. Attica,

Thank you for your comments on the article. This is my back story and why I asked about egg yolks. I am a lean 65 year old who exercises daily and avoids sucrose and high glycemic foods – following a low glycemic diet (protein and veggies) for over twenty years. My doc uses the NMR Lipoprofile. My traditional markers are always well within range but particle number and size values are not optimal. For example, LDL-P is approximately 1200. I have been working with a naturopathic doc to try to improve these values. I added eggs to my diet (1-2/day) as a protein source last year. My lab valves all significantly improved with one major exception. My LP Plac2 values increased < 50 to 255. My docs were shocked but offered no explanation. So now I'm stuck in the quandary of wanting to maintain the optimal lipid profiles while addressing the inflammatory marker. I was thinking about avoiding or drastically reducing egg yolks (reducing extra dietary cholesterol and arachidonic acid) and supplementing with choline but realizing that this may be flawed reasoning. Any thoughts or insight on how to approach this dilemma?

Dr. Attia,

I’ve also been attempting to locate information regarding non vascular causes of elevated Plac 2, but have not finding anything on google scholar or pub med. Do you have any suggestions?

LDL-associated PLA2 (PLAC) (Info from Cleveland Clinic website)

This blood test measures the level of lipoprotein associated-phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2), an enzyme associated with inflammation, stroke and heart attack risk. However, elevated levels also may be due to non-arterial causes.

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/heart/services/tests/labtests/testscad.aspx

Yes, there are no doubt some false positives. I suspect there are false negatives, too. Speaks to the need for a triangulating approach. This is why, at least in my clients, I use many markers and modalities (e.g., lipids, inflammatory markers, CIMT, family history, genetic markers).

Dr. Attia,

Hmm, I think a retest might be informative. Thank you for giving your time and knowledge to help others.

Hi Peter,

Just spotted this article linked in Sisson’s website:

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/02/130227151254.htm

Not sure you mentioned some of the things studied by Mr. Fred Kummerow in this otherwise amazing series of articles!

J.

I’m actually not familiar with this gentleman, but he observations seems reasonable.

Hi there,

Wow, great information. I am a Critical Care Paramedic, and participate in daily workouts, weights, cardio ( burn some 350 calories) and stretching. i have been unable, at age 56, to reduce my abdominal fat. It is clear now that the muffin and pie that I consume is killing me, too much sugar. While I look to remove that from my diet, I am intrigued by the Vegan diet, and its seemingly profound benefits, documented by Dr.C.Campbell and Dr. Esselstyn, I am considering making a bold move in a dietary sense. I have not been successful just with exercise and their comments certainly seem pragmatic. I do have a family history of cardiac risk with elevated cholesterol and a CT scan which demonstrated scaring at my LAD.

What do you think?

Cheers,

Richard

Hi Peter,

Have very much enjoyed the series. I know you cannot provide medical advice but am curious as to what you think is a better measurement, if you had to choose, LDL-P or Apolipoprotein B. After about 8 months of basically removing most sugar, exercising 4 times a week and dropping 20 lbs, I got my LDL-P down to 1461- from over 2100. My ApoB is 89. I’m curious as if both measurements are available, what is the best measurement to look at? Looking forward to part X

Best regards

Mike

If the LDL-P is measured with NMR, it is probably more important than apoB.

Hello Peter!

I want to sincerely thank you for all this free information on heart health. I’m a Danish paramedic and I read a lot of science and health blogs as a little hobby probably spawned by my work. It’s very interesting to learn what really goes on “behind” the endless ECG’s. You are definitely one of my “regulars” along with Chris Masterjohn, Chris Kresser, Mark Sisson and Gary Taubes. Keep up the great work!

I run kind of an n=1 experiment featuring myself from time to time. This time it’s rice MicroRNA and the impact on LDL receptors. I have a doctor who willingly has blood tests done on me when I ask him nicely. (He’s very interested in nutrition and sees the point in experimenting, although he does tend to think that 3 eggs a day and the lauric acid in coconut is gonna kill me!) Normally it’s a standard lipid panel, but this time I had an ApoB/Apoa1 test done and sent to the States Serum Institute for analysis. I’m waiting for the results right now. However, I honestly don’t know what numbers to expect or what to hope for. What would be some heart-healthy numbers for this test (ApoB and ApoA1 values) apart from a low ratio? I have searched a lot for this information but somehow it has escaped my attention. Would you be able to help me out?

I discovered this blog last night and have spent most of the last 24 hours getting up to speed and I am giddy with excitement. I’ve been attempting to follow the growing scholarship over sugar and its effects on blood chemistry and cholesterol, and I have been absolutely appalled at the state of nutritional observational research, as well as the state of medical advice I have received. (I can’t count the number of times I have screamed “correlation is not causation” at mainstream media…I assumed I was missing something.) I am so incredibly happy to have Dr. Attia (and some of the scholars to which he links) to synthesize current research for me. At age 30, I had my first cholesterol test (about 11 years ago). My TC was 375 (I don’t even know my specific numbers now, other than my HDL/LDL ratio was “normal”). Because I exhibit no other signs of metabolic syndrome (I look young, I’m thin and athletic), nobody seems to know quite what to do with me. I once had a cardiologist tell me that with high doses of statin, he could probably fix me and if not, not to worry, he could filter my blood of cholesterol (!!). So…that made me worry (and not visit him again). Since then, I have been prescribed a variety of statins by confused doctors that have various levels of success at bringing down LDL (and giving me very achey hips and legs), while my HDL has remained high. I’ve been consistently underwhelmed by the general profession’s knowledge of the intricacies of high cholesterol and decided to take matters into my own hands, which is how I landed here. A couple questions…when is the next volume regarding the use of pharmaceuticals coming out? I feel like I need to make a decision about statins on my own, but finding useful information is well nigh impossible. Two…how does one go about getting LDL-P and apoB tested? I know you have listed companies that do so, but…how do you actually do it? I don’t have a lot of faith that my doctor is going to have any idea. Can I direct a sample to them? Send it myself? I know this seems like a silly question. Thank you very, very much for what you are doing.

I think currently you need a doctor to order the test.

Hello Jeff, I heard Jimmy Moore recommend privatemdlabs.com as the lab he uses for his testing. No doctor is needed. Best wishes, maryann

Hi, firstly can I say I think what your doing is amazing and I love your blog. Sorry if I am posting this in the wrong area. I am from the U.K and I came across your blog from Zoe Harcombe’s forum, I started following her eating plan about 6 weeks ago and because of the way I am, I cant just take her word for it, I have to find real evidence that what I am doing is the right thing, hence why I like your blog! I have a question that I hope you may be able to advise me on.

I had my gallbladder removed last October and I have read on zoe’s forum that because I don’t have a gallbladder I may not be able to absorb the nutrient’s from the fat I am eating and that I may even store some of the fats, which obviously I don’t want to do. I have read a lot about people gaining weight after gallbladder surgery, which would be explained if your storing fat and not digesting it properly. I have read that taking bile salts can help with this but have also read that bitters (herbs) would be a better option because they would stimulate my liver to produce more bile, today I read else where that in fact bitters are not recommended after gallbladder removal. So as you can imagine I am quite confused as to what is the best thing to do. I know you cant advise me medically but I am wondering if you could point me in the right direction regarding this topic, maybe a trusted website or book? I cant ask my doctor because his advise would be eat a low fat diet, that is what all the doctors say about gallbladders in the u.k.

I am an active member of ” Unofficial The Harcombe Diet” facebook page and there are a few of us on there with gallbladder problems and ones like me who don’t have gallbladders anymore, we would all be extremely grateful for any advise you may be able to offer on this subject, thanks! 🙂

This is a bit misleading, Dawn. The gallbladder is just a reservoir for bile (which the liver produces to help with fat and cholesterol absorption, among other things). Absent a GB, your livers still makes normal amounts of bile, but it’s true for that for some people status post cholecystectomy (GB removal), the absolute amount of bile delivered in one instant can be reduce. If you notice malabsorption after a fatty meal, it would suggested slowing down or spreading it out over more time is the prudent thing to do.