Want to catch up with other articles from this series?

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part I

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part II

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part III

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part IV

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part V

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part VI

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part VII

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part VIII

- The straight dope on cholesterol – Part IX

Previously, in Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V ,and Part VI of this series, we addressed these 8 concepts:

#1 — What is cholesterol?

#2 — What is the relationship between the cholesterol we eat and the cholesterol in our body?

#3 — Is cholesterol bad?

#4 — How does cholesterol move around our body?

#5 – How do we measure cholesterol?

#6 – How does cholesterol actually cause problems?

#7 – Does the size of an LDL particle matter?

#8 – Why is it necessary to measure LDL-P, instead of just LDL-C?

(No so) Quick refresher on take-away points from previous posts, should you need it:

- Cholesterol is “just” another fancy organic molecule in our body but with an interesting distinction: we eat it, we make it, we store it, and we excrete it – all in different amounts.

- The pool of cholesterol in our body is essential for life. No cholesterol = no life.

- Cholesterol exists in 2 forms – unesterified or “free” (UC) and esterified (CE) – and the form determines if we can absorb it or not, or store it or not (among other things).

- Much of the cholesterol we eat is in the form of CE. It is not absorbed and is excreted by our gut (i.e., leaves our body in stool). The reason this occurs is that CE not only has to be de-esterified, but it competes for absorption with the vastly larger amounts of UC supplied by the biliary route.

- Re-absorption of the cholesterol we synthesize in our body (i.e., endogenous produced cholesterol) is the dominant source of the cholesterol in our body. That is, most of the cholesterol in our body was made by our body.

- The process of regulating cholesterol is very complex and multifaceted with multiple layers of control. I’ve only touched on the absorption side, but the synthesis side is also complex and highly regulated. You will discover that synthesis and absorption are very interrelated.

- Eating cholesterol has very little impact on the cholesterol levels in your body. This is a fact, not my opinion. Anyone who tells you different is, at best, ignorant of this topic. At worst, they are a deliberate charlatan. Years ago the Canadian Guidelines removed the limitation of dietary cholesterol. The rest of the world, especially the United States, needs to catch up. To see an important reference on this topic, please look here.

- Cholesterol and triglycerides are not soluble in plasma (i.e., they can’t dissolve in water) and are therefore said to be hydrophobic.

- To be carried anywhere in our body, say from your liver to your coronary artery, they need to be carried by a special protein-wrapped transport vessel called a lipoprotein.

- As these “ships” called lipoproteins leave the liver they undergo a process of maturation where they shed much of their triglyceride “cargo” in the form of free fatty acid, and doing so makes them smaller and richer in cholesterol.

- Special proteins, apoproteins, play an important role in moving lipoproteins around the body and facilitating their interactions with other cells. The most important of these are the apoB class, residing on VLDL, IDL, and LDL particles, and the apoA-I class, residing for the most part on the HDL particles.

- Cholesterol transport in plasma occurs in both directions, from the liver and small intestine towards the periphery and back to the liver and small intestine (the “gut”).

- The major function of the apoB-containing particles is to traffic energy (triglycerides) to muscles and phospholipids to all cells. Their cholesterol is trafficked back to the liver. The apoA-I containing particles traffic cholesterol to steroidogenic tissues, adipocytes (a storage organ for cholesterol ester) and ultimately back to the liver, gut, or steroidogenic tissue.

- All lipoproteins are part of the human lipid transportation system and work harmoniously together to efficiently traffic lipids. As you are probably starting to appreciate, the trafficking pattern is highly complex and the lipoproteins constantly exchange their core and surface lipids.

- The measurement of cholesterol has undergone a dramatic evolution over the past 70 years with technology at the heart of the advance.

- Currently, most people in the United States (and the world for that matter) undergo a “standard” lipid panel, which only directly measures TC, TG, and HDL-C. LDL-C is measured or most often estimated.

- More advanced cholesterol measuring tests do exist to directly measure LDL-C (though none are standardized), along with the cholesterol content of other lipoproteins (e.g., VLDL, IDL) or lipoprotein subparticles.

- The most frequently used and guideline-recommended test that can count the number of LDL particles is either apolipoprotein B or LDL-P NMR, which is part of the NMR LipoProfile. NMR can also measure the size of LDL and other lipoprotein particles, which is valuable for predicting insulin resistance in drug naïve patients, before changes are noted in glucose or insulin levels.

- The progression from a completely normal artery to a “clogged” or atherosclerotic one follows a very clear path: an apoB containing particle gets past the endothelial layer into the subendothelial space, the particle and its cholesterol content is retained, immune cells arrive, an inflammatory response ensues “fixing” the apoB containing particles in place AND making more space for more of them.

- While inflammation plays a key role in this process, it’s the penetration of the endothelium and retention within the endothelium that drive the process.

- The most common apoB containing lipoprotein in this process is certainly the LDL particle. However, Lp(a) and apoB containing lipoproteins play a role also, especially in the insulin resistant person.

- If you want to stop atherosclerosis, you must lower the LDL particle number. Period.

- At first glance it would seem that patients with smaller LDL particles are at greater risk for atherosclerosis than patients with large LDL particles, all things equal.

- “A particle is a particle is a particle.” If you don’t know the number, you don’t know the risk.

- With respect to laboratory medicine, two markers that have a high correlation with a given outcome are concordant – they equally predict the same outcome. However, when the two tests do not correlate with each other they are said to be discordant.

- LDL-P (or apoB) is the best predictor of adverse cardiac events, which has been documented repeatedly in every major cardiovascular risk study.

- LDL-C is only a good predictor of adverse cardiac events when it is concordant with LDL-P; otherwise it is a poor predictor of risk.

- There is no way of determining which individual patient may have discordant LDL-C and LDL-P without measuring both markers.

- Discordance between LDL-C and LDL-P is even greater in populations with metabolic syndrome, including patients with diabetes. Given the ubiquity of these conditions in the U.S. population, and the special risk such patients carry for cardiovascular disease, it is difficult to justify use of LDL-C, HDL-C, and TG alone for risk stratification in all but the most select patients.

- To address this question, however, one must look at changes in cardiovascular events or direct markers of atherosclerosis (e.g., IMT) while holding LDL-P constant and then again holding LDL size constant. Only when you do this can you see that the relationship between size and event vanishes. The only thing that matters is the number of LDL particles – large, small, or mixed.

Concept #9 – Does “HDL” matter after all?

Last week was the largest annual meeting of the National Lipid Association (NLA) in Phoenix, AZ. The timing of the meeting could not have been better, given the huge buzz going around on the topic of “HDL.” (If you’re wondering why I’m putting HDL in quotes, I’ll address it shortly.)

What buzz, you ask? Many folks, including our beloved health columnists at The New York Times, are talking about the death of the HDL hypothesis – namely, the notion that HDL is the “good cholesterol.”

Technically, this “buzz” started about 6 years ago when Pfizer made headlines with a drug in their pipeline called torcetrapib. Torcetrapib was one of the most eagerly anticipated drugs ever, certainly in my lifetime, as it had been shown to significantly raise plasma levels of HDL-C. You’ll recall from part II of this series, HDL particles play an important role in carrying cholesterol from the subendothelial space back to the liver via a process called reverse cholesterol transport (RCT). Furthermore, many studies and epidemiologic analyses have shown that people with high plasma levels of HDL-C have a lower incidence of coronary artery disease.

In the case of torcetrapib, there was an even more compelling reason to be optimistic. Torcetrapib blocked the protein cholesterylester transfer protein, or CETP, which facilitates the collection and one-to-one exchange of triglycerides and cholesterol esters between lipoproteins. Most (but not all) people with a mutation or dysfunction of this protein were known to have high levels of HDL-C and lower risk of heart disease. Optimism was very high that a drug like torcetrapib, which could mimic this effect and create a state of more HDL-C and less LDL-C, would be the biggest blockbuster drug ever.

The past month or so has seen this discussion intensify, which I’ll quickly try to cover below.

The data

Torcetrapib

After several smaller clinical trials showed that patients taking torcetrapib experienced both an increase in HDL-C and a reduction in LDL-C, a large clinical trial pitting atorvastatin (Lipitor) against atorvastatin + torcetrapib was underway. This trial was to be the jewel in the crown of Pfizer. It was already known that Lipitor reduced coronary artery disease (and reduced LDL-C, though this may have been a bystander effect and real reduction in mortality may be better attributed to the reduction in LDL-P).

I still remember exactly where I was standing, on the corner of Kerney St. and California St. in the heart of San Francisco’s financial district, on that December day back in 2006 when it was announced the trial had been halted because of increased mortality in the group receiving torcetrapib. In other words, adding torcetrapib actually made things worse. I was shocked.

Many reasons were offered for this, including the notion that torcetrapib was, indeed, helpful, but because of unanticipated side-effects, (raising blood pressure in some patients and altering electrolyte balance in others), the net impact was harmful. Some even suggested that the drug could be useful in the “right” patients (e.g., those with low HDL-C, but normal blood pressure). Furthermore, in two subsequent studies looking at carotid IMT (thickening of the carotid arteries) and intravascular ultrasound, there was no reduction in atherosclerosis.

This was a big strike against the HDL hypothesis and work on torcetrapib was immediately halted.

Niacin

Niacin has long been known to raise HDL-C and has actually been used therapeutically for this reason for many years. The AIM-HIGH trial (Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with Low HDL/High Triglycerides – you can’t have trials in medicine without catchy names!) sought to test this. The trial randomly assigned over 3,000 patients with known and persistent, but stable and well treated cardiovascular risk, to one of two treatments:

- Simvastatin (40-80 mg/day), +/- ezetimibe (10 mg/day) as necessary to maintain LDL-C below 70 mg/dL + placebo (a tiny dose of crystalline niacin to cause flushing);

- As above, but instead of a placebo, patients were given 1,500 to 2,000 mg/day of extended-release niacin.

Both arms of the study had their LDL-C < 70 mg/dL, non-HDL-C < 100 md/dL and apoB < 80 mg/dL, but despite the statin or statin + ezetimibe treatment still had low HDL-C. So, if niacin raised HDL-C and reduced events, the HDL raising hypothesis would be proven.

Simvastatin, as its name suggests, is a statin which primarily works by blocking HMG-CoA reductuse, an enzyme necessary to synthesize endogenous cholesterol. Ezetimibe works on the other end of problem, by blocking the NPC1L1 transporter on gut enterocytes and hepatocytes at the hepatobiliary junction (for a quick refresher, go back to part I of this series and look at the second figure – ezetimibe blocks the “ticket taker” in the bar).

After two years the niacin group, as expected, had experienced a significant increase in plasma HDL-C (along with some other benefits like a greater reduction in plasma triglycerides). However, there was no improvement in patient survival. The trial was futile and the data and safety board halted the trial. In other words, for patients with cardiac risk and LDL-C levels at goal with medication niacin, despite raising HDL-C and lowering TG, did nothing to improve survival. This was another strike against the HDL hypothesis.

Dalcetrapib

By 2008, as the AIM-HIGH trial was well under way, another pharma giant, Roche, was well into clinical trials with another drug that blocked CETP. This drug, a cousin of torcetrapib called dalcetrapib, albeit a weaker CETP-inhibitor, appeared to do all the “right” stuff (i.e., it increased HDL-C) without the “wrong” stuff (i.e., it did not appear to adversely affect blood pressure). It did nothing to LDL-C or apoB.

This study, called dal-OUTCOMES, was similar to the other trials in that patients were randomized to either standard of care plus placebo or standard of care plus escalating doses of dalcetrapib. A report of smaller safety studies (called dal-Vessel and Dal-Plaque) was published a few months ago in the American Heart Journal, and shortly after Roche halted the phase 3 clinical trial. Once again, patients on the treatment arm did experience a significant increase in HDL-C, but failed to appreciate any clinical benefit. Another futile trial.

Currently, two additional CETP inhibitors, evacetrapib (manufactured by Lilly) and anacetrapib (manufactured by Merck) are being evaluated. They are much more potent CETP inhibitors and, unlike dalcetrapib, also reduce apoB and LDL-C and Lp(a). Both Lilly and Merck are very optimistic that their variants will be successful where Pfizer’s and Roche’s were not, for a number of reasons including greater anti-CETP potency.

Nevertheless, this was yet another strike against the HDL hypothesis because the drug only raised HDL-C and did nothing to apoB. If simply raising HDL-C without attacking apoB is a viable therapeutic strategy, the trial should have worked. We have been told for years (by erroneous extrapolation from epidemiologic data) that a 1% rise in HDL-C would translate into a 3% reduction in coronary artery disease. These trials would suggest otherwise.

Mendelian randomization

On May 17 of this year a large group in Europe (hence the spelling of randomization) published a paper in The Lancet, titled, “Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: a mendelian randomisation study.” Mendelian randomization, as its name sort of suggests, is a method of using known genetic differences in large populations to try to “sort out” large pools of epidemiologic data.

In the case of this study, pooled data from tens of studies where patients were known to have myocardial infarction (heart attacks) were mapped against known genetic alterations called SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms, pronounced “snips”). I’m not going to go into detail about the methodology because it would take 3 more blog posts., But, the reason for doing this analysis was to ferret out if having a high HDL-C was (only) correlated with better cardiovascular outcome, which has been the classic teaching, or if there was any causal relationship. In other words, does having a high HDL-C cause you to have a lower risk of heart disease or is it a marker for something else?

This study found, consistent with the trials I’ve discussed above, that any genetic polymorphism that seems to raise HDL-C does not seem to protect from heart disease. That is, patients with higher HDL-C due to a known genetic alteration did not seem to have protection from heart disease as a result of that gene. This suggests that people with high or low HDL-C who get coronary artery disease may well have something else at play.

Oh boy. This seems like the last nail in the casket of the entire “HDL” hypothesis, as evidenced by all of the front page stories worldwide.

The rub: the difference between HDL-C and HDL-P

The reason I’ve been referring to high density lipoprotein as “HDL,” unless specifically referring to HDL-C, is that HDL-P and HDL-C are not the same thing. Just as you are now intimately familiar with the notion that LDL-C and LDL-P are not the same thing, the same is true for “HDL” which simply stands for high density lipoprotein, and like LDL is not a lab assay. In fact, unpublished data from the MESA trial found that the correlation between HDL-C and HDL-P was only 0.73, which is far from “good enough” to say HDL-C is a perfect proxy for HDL-P.

HDL-C, measured in mg/dL (or mmol/L outside of the U.S.), is the mass of cholesterol carried by HDL particles in a specified volume (typically measured as X mg of cholesterol per dL of plasma). HDL-P is something entirely different. It’s the number of HDL particles (minus unlipidated apoA-I and prebeta-HDLs: at most 5% of HDL particles) contained in a specified volume (typically measured as Y micromole of particles per liter).

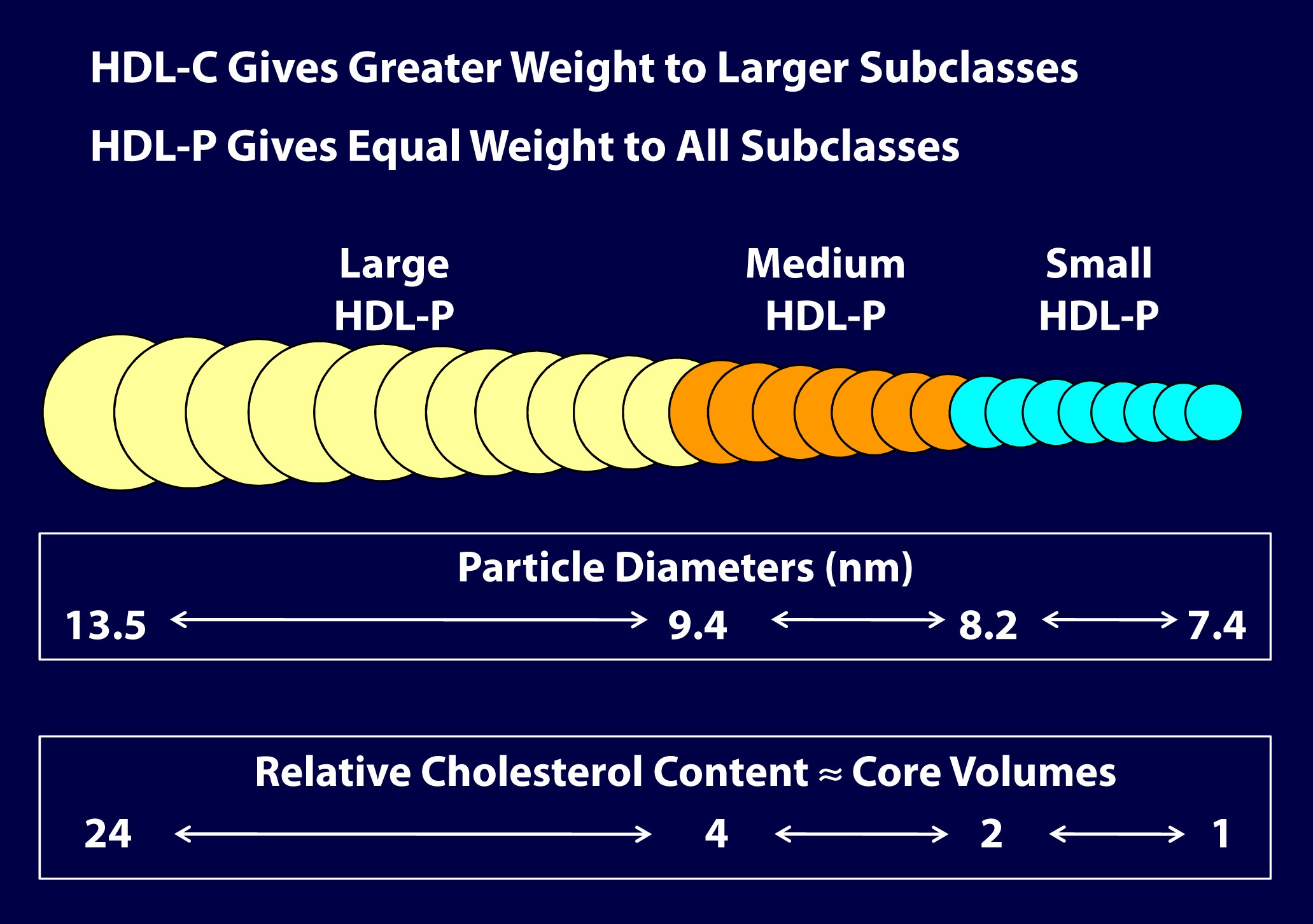

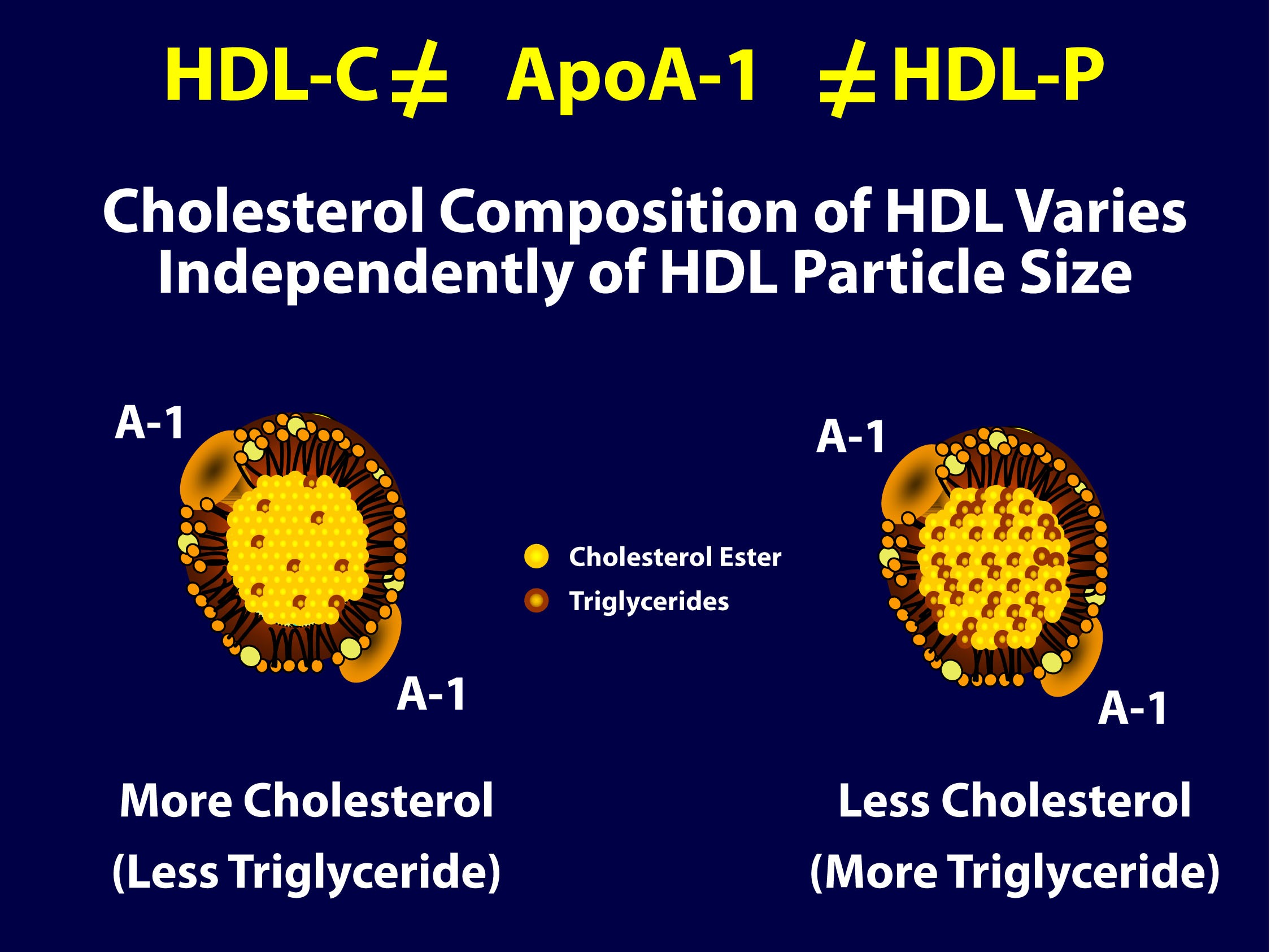

As you can see in the figure below (courtesy of Jim Otvos’ presentation at the NLA meeting 2 weeks ago), the larger an HDL particle, the more cholesterol it carries. So, an equal number of large versus small HDL particles (equal HDL-P) can carry very different amounts of cholesterol (different HDL-C). Of course, it’s never this simple because HDL particles, like their LDL counterparts, don’t just carry cholesterol. They carry triglycerides, too. Keep in mind, HDL core CE/TG ratio is about 10:1 or greater – if the large HDL carries TG, it will not be carrying very much cholesterol.

So, the important point is that HDL-C is not the same as HDL-P (which is also not the same as apoAI, as HDL particles can carry more than one apoAI).

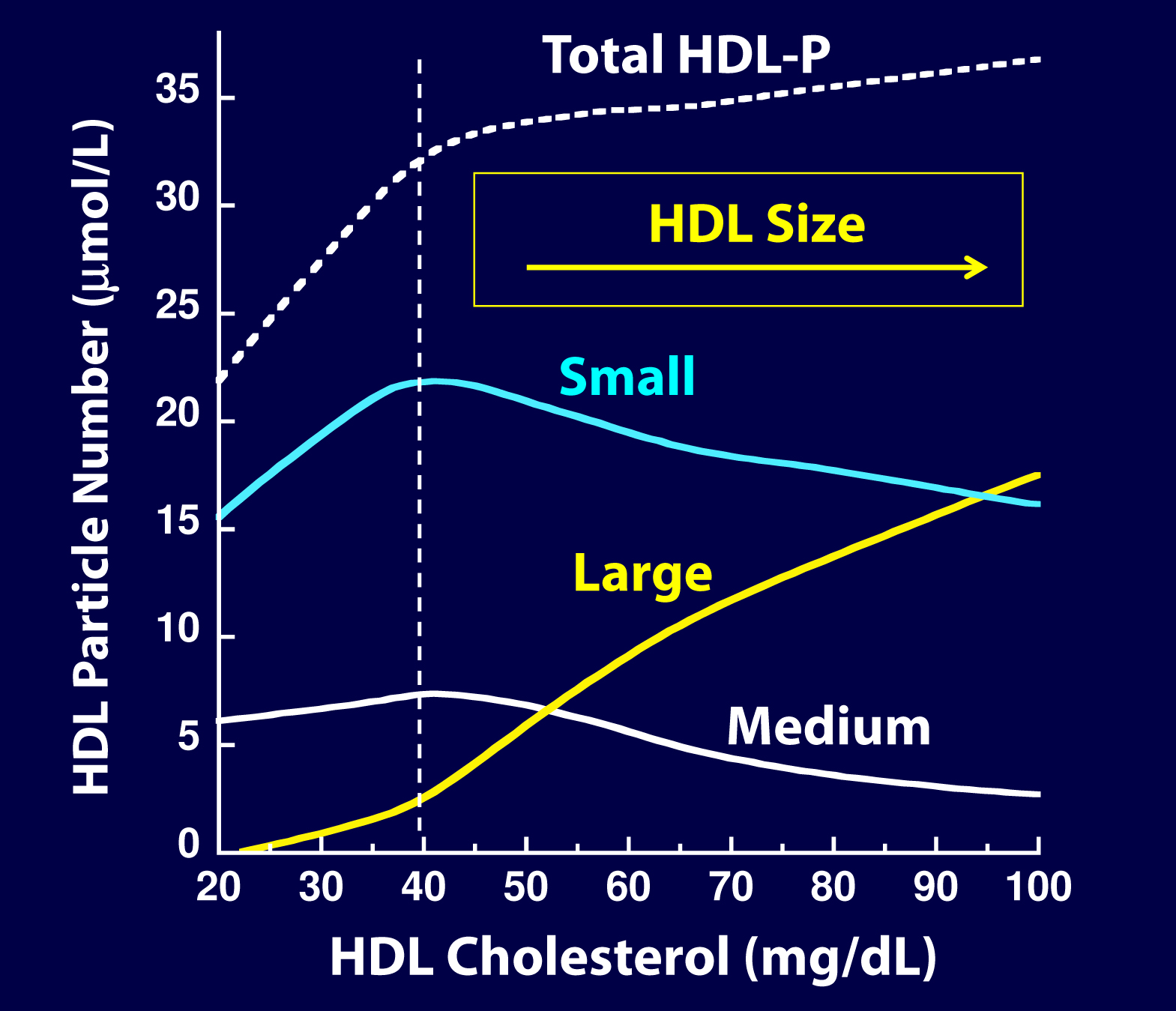

But there’s something else going on here. If you look at the figure below, from the Framingham cohort, you’ll note something interesting. As HDL-C rises, it does so not in a uniform or “across the board” fashion. A rise in HDL-C seems to disproportionately result from an increase in large HDL particles. In other words, as HDL-C rises, it doesn’t necessarily mean HDL-P is rising at all, and certainly not as much.

As you can see, for increases in HDL-C at low levels (i.e., below 40 mg/dL) the increase in small particles seems to account for much of the increase in total HDL-P, While for increases over 40 mg/dL, the increase in large particles seems to account for the increase in HDL-C. Also note that as HDL-C rises above 45 mg/dL, there is almost no further increase in total HDL-P – the rise in HDL-C is driven by enlargement of the HDL particle – more cholesterol per particle – not the drop in small HDL-P. This reveals to us that the small HDL particles are being lipidated.

Is there a reason to favor small HDL particles over large ones?

In the 2011 article, “Biological activities of HDL subpopulations and their relevance to cardiovascular disease,” published in Trends in Molecular Medicine, the authors describe in great detail some of protective mechanisms imparted by HDL particles.

Large HDL particles may be less protective and even dysfunctional in certain pathological states, whereas small to medium-sized HDL particles seem to confer greater protection through the following mechanisms:

- Greater antioxidant activity

- Greater anti-inflammatory activity

- Greater cholesterol efflux capacity

- Greater anti-thrombotic properties

In other words, particle for particle, it seems a small HDL particle may be better at transporting cholesterol from the subendothelial space (technically, they acquire cholesterol from cholesterol-laden macrophages or foam cells in the subedothelial space) elsewhere, better at reducing inflammation, better at preventing clotting, and better at mitigating the problems caused by oxidative free radicals.

Of course, reality is complicated. If there was no maturation from small to large HDL particles (i.e., the dynamic remodeling of HDL), the system would be faulty. So, the truth is that all HDL sizes are required and that HDL particles are in a constant dynamic state (or “flux”) of lipidating and delipidating, and the real truth is no particular HDL size can be said to be the best. If the little HDLs do not enlarge, the ApoA-I mediated lipid trafficking system is broken.

The truth about the old (and overly simplistic) term called reverse cholesterol transport (RCT)

HDL particles traffic cholesterol and proteins and last in plasma on average for 5 days. They are in a constant state of acquiring cholesterol (lipidation) and delivering cholesterol (delipidation). There are membrane receptors on cells that can export cholesterol to HDL particles (sterol efflux transporters) or extract cholesterol or cholesterol ester from HDL particles (sterol influx transporters).

The vast majority of lipidation occurs (in order): 1) at the liver, 2) the small intestine, 3) adipocytes and 4) peripheral cells, including plaque if present. The liver and intestine account for 95% of this process. The amount of cholesterol pulled out of arteries (called macrophage reverse cholesterol transport) is critical to disease prevention but is so small it has no effect on serum HDL levels. Even in patients with extensive plaque, the cholesterol in that plaque is about 0.5% of total body cholesterol. HDL particles circulate for several days as a ready reserve of cholesterol: almost no cell in humans require a delivery of cholesterol as cells synthesize all they need. However, steroidogenic hormone producing tissues (e.g., adrenal cortex and gonads) do require cholesterol and the HDL particle is the primary delivery truck.

If, as is the case in a medical emergency, the adrenal gland must rapidly make a lot of cortisone, the HDL particles are there with the needed cholesterol. This explains the low HDL-C typically seen in patients with severe infections (e.g., sepsis) and severe inflammatory conditions (e.g., Rheumatoid Arthritis).

Sooner or later HDL particles must be delipidated, and this takes place at: 1) the adrenal cortex or gonads 2) the liver, 3) adipocytes, 4) the small intestine (TICE or transintestinal cholesterol efflux) or give its cholesterol to an apoB particle (90% of which are LDLs) to return to the liver. A HDL particle delivering cholesterol to the liver or intestine is called direct reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), whereas a HDL particle transferring its cholesterol to an apoB particle which returns it to the liver is indirect RCT. Hence, total RCT = direct RCT + indirect RCT.

The punch line: a serum HDL-C level has no known relationship to this complex process of RCT. The last thing a HDL does is lose its cholesterol. The old concept that a drug or lifestyle that raises HDL-C is improving the RCT process is wrong; it may or may not be affecting that dynamic process. Instead of calling this RCT, it would be more appropriately called apoA-I trafficking of cholesterol.

Why do drugs that specifically raise HDL-C seem to be of little value?

As I’ve argued before, while statins are efficacious at preventing heart disease, it’s sort of by “luck” as far as most prescribing physicians are concerned. Most doctors use cholesterol lowing medication to lower LDL-C, not LDL-P. Since there is an overlap (i.e., since the levels of LDL-P and LDL-C are concordant) in many patients, this misplaced use of statins seems to work “ok.” I, and many others far more knowledgeable, would argue that if statins and other drugs were used to lower LDL-P (and apoB), instead of LDL-C, their efficacy would be even greater. The same is true for dietary intervention.

Interestingly, (and I would have never known this had Jim Otvos not graciously spent a hour on the phone with me two weeks ago giving me a nuanced HDL tutorial), a study that went completely unnoticed by the press in 2010, published in Circulation, actually did a similar analysis to the Lancet paper, except that the authors looked at HDL-P instead of HDL-C as the biomarker and looked at the impact of phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) on HDL metabolism. In this study, though not the explicit goal, the authors found that an increase in the number of HDL particles and smaller HDL particles decreased the risk of cardiovascular disease. The key point, of course, is that the total number of HDL particles rose, and it was driven by increased small HDL-P. The exact same thing was seen in the VA-HIT trial: the cardiovascular benefit of the treatment (fibrate) was related to the rise in total HDL-P which was driven by the fibrates’ ability to raise small HDL-P.

It seems the problem with the “HDL hypothesis” is that it’s using the wrong marker of HDL. By looking at HDL-C instead of HDL-P, these investigators may have missed the point. Just like LDL, it’s all about the particles.

Summary

- HDL-C and HDL-P are not measuring the same thing, just as LDL-C and LDL-P are not.

- Secondary to the total HDL-P, all things equal it seems smaller HDL particles are more protective than large ones.

- As HDL-C levels rise, most often it is driven by a disproportionate rise in HDL size, not HDL-P.

- In the trials which were designed to prove that a drug that raised HDL-C would provide a reduction in cardiovascular events, no benefit occurred: estrogen studies (HERS, WHI), fibrate studies (FIELD, ACCORD), niacin studies, and CETP inhibition studies (dalcetrapib and torcetrapib). But, this says nothing of what happens when you raise HDL-P.

- Don’t believe the hype: HDL is important, and more HDL particles are better than few. But, raising HDL-C with a drug isn’t going to fix the problem. Making this even more complex is that HDL functionality is likely as important, or even more important, than HDL-P, but no such tests exist to “measure” this.

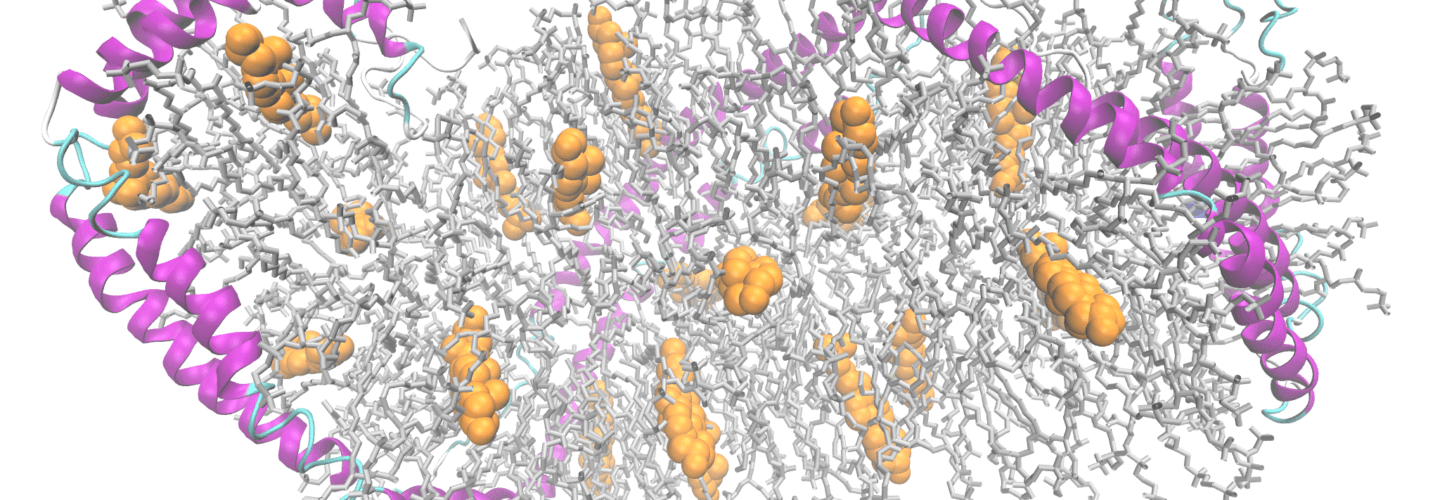

Two apolipoprotein A1 chains (magenta ribbons) complexed with cholesterol (orange balls) and phospholipids, after PDB 3K2S by Ayacop [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Hi Peter,

This series has been one of the most informative series and I really appreciate your effort. As my knowledge and awareness of cholesterol has increased many fold, I am finding it harder to make sense of my cardiologist who still talks to me in terms of good/bad cholesterol. I have thoughts of printing this series and presenting it to him for his bedtime reading but that would essentially end our relationship. My FP is worse. He is so afraid of eating saturated fat that he won’t allow me to eat eggs and he is still wondering how I managed to raise my HDL-C from a measly 23 to 55 (thanks to 4-6 eggs I eat everyday)

I guess I was happier when eating “healthy” vegetarian lifestyle and everybody telling me how good I was! I just have to find a doctor who is not afraid to have an open mind and up to date on all this research you and others write about.

Thanks again for this wonderful series.

Phil, I hate to suggest this, as it’s not my place, but have you considered looking for new doctors?

I’ve never bought into the reverse cholesterol transport theory. I’m much more interested in the role of HDL-associated proteins such as paraoxonase, which is known to metabolize oxidized lipids (which we know can become trapped in the endothelial space). If you have small dense LDL with lots of omega-6 fats, these fats will easily oxidize, and the oxidized lipids act as potent inflammation triggers, leading to atherosclerosis. The paraoxonase (from the HDL) can help deal with this problem. Just measuring the cholesterol levels tells you nothing useful.

“the binary view (“Everyone should be on statins” versus “Statins are horrible and should be abolished”) is utterly baseless and naive. Statins are a tool. Simple and plain. Use the tool for the RIGHT job at the RIGHT time, and it helps. If you don’t, it doesn’t, and it might cause harm.”

I assume you are referring to our discussion here. I want to go on record as disassociating myself with what I would call a parody of my view on statins. Its hard to argue with maxims like “right tool for the right job” but I would counter with another old standby “when the only tool you have is a hammer, then every problem looks like a nail.” Enough said.

“There is no one number that is “perfect” and there is no test, even LDL-P, that should be taking in complete isolation.”

Glad to hear you say that. Even if we disagree on when, whether, or if an NMR is warranted, we seem to agree on integrating a larger set of information. That was far from clear from our earlier discussion.

Some additional thoughts:

1) Has anybody ever considered evaluating LDL-P/HDL-P as a risk marker.? Not sure we need yet another one of those but it would solve the units of measurement issue.

2) Kudos to lorraine for raising the issue of inflammation……’

3) I am doing some interesting reading on insulin resistance and HDL-P. I have some thoughts but they are not yet ready for prime time.

Hasan, I was not referring to you when I made that statement. It’s a very broad statement reflecting a view held by many. Also, I agree that when you only have a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Fortunately, we have an entire tool kit.

” It would seem that forcing the body to make more HLD-C upsets the balance of the system and that there is a different mechanism in play when drugs are in play versus someone who has naturally occuring high HDL-C”

The recent Mendelian randomization study:

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2812%2960312-2/fulltext

has also cast some doubt on the idea that “naturally occurring” HDL is protective. While this is not the end of the story, it may be once again that HDL is only a risk marker that covaries with insulin resistance and that natural variations in HDL levels have no inherent meaning. It does seem that wherever I look, insulin resistance rears its ugly head!

” it may be once again that HDL is only a risk marker ”

Commenting on own comment, I want to head off any misunderstanding I may have created by bad phrasing. I don’t mean to suggest that HDL has no other function other than as a risk marker only that all lipid markers have to be looked in a larger context rather than as meaningful in and of themselves. I hope that makes sense.

I am wondering if the effort of drug companies to start to focus on HDL effecting drugs is a result of the fact that there are still way to many heart incidents for many who are already on statins? Of course, the reason for this is focus by to many physicians(and maybe drug co’s)on LDL-C and not LDL-P. Not to say that raising HDL-P won’t be helpful, particularly in combination with lowering LDL-P, and for those who already have some CAD,but it appears that overwhelmingly the emphasis should be on lowering LDL-P.

Tim Russert was a prime example of this: low LDL-C of under 70, but no idea where his particles were. Am betting above 1,000.

Since NMR measures LDL-P particles in the bloodstream not taken up by the liver( I think?) then something has to happen to these particles regardless of the number of them. It would be my guess that they degrade and regardless of amount, as they get smaller, particularly in a person in an inflammatory state, not only penetrate the endothelial layer, but are of the oxidized variety setting off the whole process of CAD. Any thoughts about this?

From my point of view, the posts are not to technical. I would find it hard to understand if you did not go in to the science.

I do think there are certain things not yet answered: cholesterol may not matter, but can the same be said for sat fat and its impact on LDL-P?

Thanks for all your hard work. You are providing us with an amazing education to allow us to go about how we want to address the risk of heart disease which remains the number one killer of far to many, way to soon.

Tim Russert’s LDL-C, as you note, was under 70 mg/dL. His TG was about 380 mg/dL, if I recall. If I were a betting man, I would have guessed his LDL-P was over 3,000 nmol/L. His LDL particles carried virtually all TG and very little CE. Of course, his doctors didn’t need an NMR to measure his risk. His TG alone was an elephant in the room. But most doctors aren’t thinking through these issues. LDL-C, and even non-HDL-C, are really, really primitive. TG/HDL-C is probably better. apoB to apoAI is excellent, and recent data would suggest LDL-P to HDL-P is especially good [ratio of LDL-P to HDL-P less than 30 is ideal].

Peter,

I have been looking around for doctors who are following up new research and aren’t afraid to challenge conventional wisdom. My hospital publishes many of its doctor’s philosophy and answers to questions. As I poured through those, it was clear to me that there is either no useful information about what they actually believe in and then there are those who stress the same old ideas.

One of the questions was about coconut oil. The Doctor’s answer revolved around the nature of coconut fat, lack of conclusive studies and advice to avoid eating it. The last thing he stated was the (supposedly) high incidence of CHD in some parts of South India where a lot of coconut oil is used in cooking. And he was one of the few that I thought worth checking out! He also considers rice to be as bad as fat (some consolation there!).

My frustration is that my doctors don’t seem to have time for anything but routine tests and medication. My doctor continues to do the standard lipid profile and talks to me about good and bad cholesterol every six months! He looks at me as if I am nuts when ask him about cholesterol density and particles. I can almost visualize the rolling of eyes 🙂

Thanks for your advise. I will continue my search for a good doctor and hope it ends up well.

So sorry to hear that. NuSI has a lot of work to do.

I’m currently pondering the same issue raised here, as elsewhere in the comments to this latest post.

How do I find a doctor who will accept a patient eating high fat, moderate protein, and very low carb?

How do we find our own Dr Westman, or Dr Phinney?

Patrick

If I knew I’d tell you. I think it just takes a lot of time and diligence. It’s no different than buying a house or a car. Nobody does something like that without REALLY shopping around, right? Yet how many folks just “show up” in their doctor’s office? I was very lucky. 1) My doctor was naturally very open to my “crazy” idea for how I was going to cure my metabolic syndrome 2) As a doctor, it probably but me more slack in pushing the envelope.

You may not have factor #2 in your favor, but you can shop around until you find factor #1 in your favor.

Yeah, can you get on the NuSI thing? 😉 There is a decided lack of forward-thinking doctors here on the East coast. I think we have 2 in Maryland on Jimmy Moore’s site. 🙁

I’m very lucky in that my doctor is a believer – sort of. He saw what I did, he read Gary Taubes, gave the book to his other patients, etc. BUT, when I run up against a block, he really doesn’t know what to do. Last time he suggested bariatric surgery! (I said absolutely not.)

Folks, Jimmy Moore maintains a “low-carb doctor” blog list. You can check it for a doctor in your area who may be accepting of a lo carb diet. See:

https://lowcarbdoctors.blogspot.com/

Thanks for your response, Peter.

I’m keen to find a doctor primarily because I would like a prescription for a ketone meter and strips. My insurance company will apparently cover a free Precision xtra meter, and reduce the cost of the ketone and glucose test strips, but the catch is that I must have a prescription. So either I try to persuade my doctor to provide one, which I anticipate will be a sisyphean labor, or I find a doctor already “concordant” with the idea of ketogenic eating.

I am not diabetic, not suffering from metabolic syndrome (or anything else). Lucky me. But I would like to know about the ketone levels I’m producing, as I tweak the fat and protein in my daily eating.

I mention this because other readers here, especially those with a doctor already well informed, can perhaps take advantage of the reduced costs of a meter and test strips via a prescription.

Patrick

Hi Peter,

Thanks for another rewarding post.

I have one request: please don’t start spacing out these “hard” posts with “lighter” ones. Yes, the subject is difficult and the discussion is exhaustive (I didn’t say “exhausting”) — but the subject is crucially important, and you are laying to rest some important mistakes that we have been taught for years.

I certainly would like to get to the conclusion, so I can say, “Well, I understand all that better,” but if you spend time on lighter subjects in between, it will just take longer to finish this one.

Notice that you are not getting a lot of comments like, “Gee, this is too hard, stop boring us….” 🙂

Fair point. The other thing I have to balance is the time it takes to write “hard” posts versus “soft” ones. Each of these cholesterol posts takes me a minimum of 12 hours to write, all of which I have to do on weekends. Cuts into family time and training time…It’s a balance for me, too.

I just listened to live radio show this morning with Dr Michael Richman, who I think may be associated somehow with Dr Dayspring through lipidcenter.com(apologies if this isn’t correct). It was interesting. He seemed very much up to date on the importance of measuring LDL-P (also sounded like a very bright guy), but boy was he certain that eating fat, particularly saturated fat, would give you heart disease. Is this the view of most lipidologists?

Actually it is. One of the reasons Tom Dayspring, Tara Dall, and others have become such good friends is that they are really open minded about learning out “my” world, just as I’m interested in learning about “theirs.” It’s a slow process to undo 40 years of bad science and nutritional “wisdom.”

To answer my own question about the LDL-p/HDL-p ratio as well as to address the assertion above that this ratio is the best risk marker for CVD. From:

https://www.lipidjournal.com/article/S1933-2874(10)00458-7/abstract

“In our large study cohort, a predictive model for future coronary events incorporating the best-available novel lipid parameter (LDL-p/HDL-p ratio) was comparable with the same model that incorporated conventional lipid ratios such as the TC/HDL-c ratio . The use of LDL-p/HDL-p ratio did not appear to offer incremental value over more traditional risk prediction models.”

So, similar to LDL-P, LDL-p/HDL-p does in fact not to seem to offer any value over the standard risk markers.

Not sure I agree, Hasan. An “ideal” ratio of LDL-P to HDL-P is probably less than 30 or 35 (when reported in the typical units – nmol/L and umol/L, respectively; if both actually in the same units, ideal ratio is less than 0.03). This ratio is actually better than TC to HDL-C or even apoB to apoA-I when used to predict CV risk. This was validated in the Women’s Health Study and VA-HIT Trial. However, ratios are never meant to be used as goals of therapy as they have not been validated for that purpose and the numerator carries far more weight than the denominator. In drug naïve patients, low risk (bottom quartile) is LDL-P to HDL-P < 35, while a ratio greater than 70 is considered high risk (top quartile). The figure that shows this can be found in Circulation 2006;113:1556-63.

” In drug naïve patients, low risk (bottom quartile) is LDL-P to HDL-P < 35, while a ratio greater than 70 is considered high risk (top quartile)….The figure that shows this can be found in Circulation 2006;113:1556-63."

Hmm…going to Circulation 2006;113:1556-63 brings us to this study:

https://m.circ.ahajournals.org/content/113/12/1556.long

which clearly CANNOT be used to evaluate LDL-P/HDL-P as a risk marker in the general population since the study was designed to test Gemfibrozil in a cohort that already had an established diagnosis of CHD. Additionally, there were the following "lipid eligibility criteria" for the participants:

"Lipid eligibility criteria were HDL-C ?40 mg/dL, LDL-C ?140 mg/dL, and triglycerides ?300 mg/dL."

In contrast, the study I cited above, this is hardly the appropriate cohort to test anything as a risk marker for the general population.

The only other study I found of LDL-P/HDL-P as a risk marker was cited by Dayspring here:

https://www.obgmanagement.com/article_pages.asp?AID=6991&UID=

who claimed that it was one of "Several epidemiologic studies that enrolled both genders found the best predictors of risk to be: elevated levels of apoB or LDL-P and reduced levels of apoA-I or HDL-P [OR} a high apoB/apoA-I ratio or LDL-P/HDL-P ratio. 6,13,14"

However, only reference 14:

https://circ.ahajournals.org/content/119/7/931.full

discussed LDL-P/HDL-P and it neither concerned both genders nor did it find LDL-P/HDL-P to be the best predictor of risk. In fact, it concluded:

"In this prospective study of healthy women, cardiovascular disease risk prediction associated with lipoprotein profiles evaluated by NMR was comparable but not superior to that of standard lipids or apolipoproteins."

Interestingly, and germane to this conversation, it also found no additional value for LDL-P itself:

"Essentially no reclassification improvement was found with the addition of the LDLNMR particle concentration or apolipoprotein B100 to a model that already included the total/HDL cholesterol ratio and nonlipid risk factors (net reclassification index 0% and 1.9%, respectively), nor did the addition of either variable result in a statistically significant improvement in the c-index."

To add to this growing body of evidence against the routine use of LDL-P is this brand new study:

https://m.circ.ahajournals.org/content/early/2012/04/20/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.073684.abstract

that concluded:

"In a population at 2% average coronary event risk per year, cholesterol, apolipoprotein, and particle measures of LDL were strongly correlated and had similar predictive value for incident major occlusive vascular events."

I think it should be very clear by this point why the a 2011 Expert Panel of Lipid Specialists:

https://www.lipid.org/uploads/300/Expert%20Panel%20Paper.pdf

does not recommend LDL-P testing for low-risk patients as as it does not appear to add any value, either alone or in a ratio, to the standard risk markers.

While it may have some value in the subset of those with insulin resistance/Met Syn, I continue to be disturbed by the assertion that LDL-P (and NMR testing) is an advance on standard risk predictors for the general population. I won't recapitulate all of my arguments against LDL-P screening which can be found above or in Part VI of this series but I will leave you with this from "Advanced Lipoprotein Testing and Subfractionation Are Not (Yet) Ready for Routine Clinical Use":

https://circ.ahajournals.org/content/119/17/2396.full#_jmp0_

'In summary, a lipoprotein measure obtained from an advanced test is clinically useful if the following criteria are met: It adds to clinical knowledge; it provides risk information that is independent of established predictors; it is easy to measure and interpret in a clinical setting; it is accurate, reproducible, and internationally standardized; and it has a favorable cost-benefit ratio.55 Importantly, the lipoprotein measures should improve patient management, particularly through more accurate risk classification and guiding choice of therapy.55,56 "

I submit that LDL-P, in the general population and alone or in a ratio with HDL-P, is not independent of established predictors, has an unknown cost-benefit ratio, and does not result in more accurate risk classification for that population. I am always willing to hear any evidence to the contrary but in the absence of that evidence, I would conclude that there is no reason at the current time for a healthy person to measure his LDL-P, via NMR or by any other means.

Yes, I misspoke about this trial being in drug naive patients and was thinking of something else. For an easier view of the paper, you can get the pdf here: https://circ.ahajournals.org/content/113/12/1556.full.pdf+html. Table 5 has a nice summary.

Before we pick on this study too much, however, we need to keep an important principle in mind. When powering a study you have a choice — A) make it as broad as possible (e.g., include young, old, sick, healthy, men, women, cats, dogs), or B) make it as narrow as possible.

Most elaborate studies do the latter for the obvious reason that an 80% power can be achieved, as in the case of this study, with 1200 patients or so. If the former, it would have required 2 million patients. That, obviously, will not happen. We trade power for applicability every single time we do these studies. When we don’t, the results often get lost in the noise.

So these are some of the natural limitations of clinical trials. What you are pointing out is true in the sense that you (I’m assuming) and I don’t fit the demographic of this study. But your conclusion, namely that it is necessarily the case that the results don’t apply, is not. It just has not been validated yet. Of course, the same is true of many things in medicine. Right or wrong, medicine often has to use interventions or diagnostic tests on a population (A) that was not appropriately represented by the studies validating it on a different population (B).

Is this ideal? No. Is there a chance of error? Of course. But we do the best we can and we continue to try to make forward progress. Almost nothing in medicine would have progressed without this challenge of conventional wisdom. If you have not already done so, the chapter on radical mastectomy in The Emperor of all Maladies (the biography of cancer) is a bold example.

In 1957 Ancel Keys and his wife Margaret would have told us, definitively, that measuring total cholesterol was enough to predict heart disease.

Today we know that is silly.

In 1984 the NIH consensus panel told us LDL-C was the best way to measure risk for CHD. Same story.

Almost certainly in 30 years we will have enough information to say marker X or ratio Y is the best predictor of disease, but today we’re at a transition point. Most of the studies (i.e., the bulk of the patient interventions) have involved “typical” markers. A select few, usually on smaller cohorts, have begun to test other markers, but as you point out, the populations may not be representative of the average “healthy” person.

Of course, the term “healthy” is misleading. How do we really define it? For any metric of healthy out there (e.g., normal glucose, insulin, TG, HDL-C), I have personally seen a dozen with hidden pathology. I know you reject this type of “individualization” of the discussion, but this is where you and I really differ.

Medicine is an art that tries to relay on science whenever possible. I take care of some people with an LDL-P of 1,400 who I suggest do nothing but continue their course. I take care of others with an LDL-P of 1,100 that I would like to see on 2 drugs. Why? It would take me an hour of typing, which I’m not going to do, to explain the differences between these patients and why the first requires only a lifestyle interaction and why the second does not.

I’m going to leave it at that and hope you can respect the fact that I can’t spend an additional hour each day defending this point. I know you disagree. Everyone else knows you disagree. We’ve reached a point of diminishing returns on this topic. Perhaps there are other topics on this blog worthy of your scrutiny. There is obviously a big discussion going around about the role of inflammation as the primary driver of CHD. This might be something to weigh in on.

I am sorry Peter but it is just not appropriate to end this discussion without me having the opportunity to respond. You are going to have a lot of people here unnecessarily running off to get NMR’s based on what appears to be wrong information. You cited two studies above to prove your point about LDL-P:

“This was validated in the Women’s Health Study and VA-HIT Trial.”

Neither one says what you claimed it did. As already discussed the VA-HIT Trial was not appropriate given the cohort and now you are arguing that it is too difficult to construct a proper study in a healthy population. Well, I am sorry to say that the Women’s Health Study, which did manage to construct a proper study of a healthy cohort (cmon, its not that hard) also does not support your claim:

https://circ.ahajournals.org/content/119/7/931.full.pdf

It says:

“To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first large, prospective comparison of associations of NMR-measured lipoproteins with both standard lipids and immunoassay measured apolipoproteins for predicting incident CVD. We found that NMR-measured total LDLNMR particle concentration was similar in CVD risk prediction to apolipoprotein B100 , and both measurements performed better than LDL cholesterol; however, the differences compared with triglycerides, non-HDL cholesterol, and the total/HDL cholesterol ratio were small and do not support the routine measurement of NMR lipoproteins or immunoassay apolipoproteins when a standard lipid panel is available. The data from the present study, along with our prior findings 14,29 and recent data from the Framingham Study, 30 provide evidence-based confirmation for guidelines that are based on the use of standard lipid measurements, particularly the total/HDL cholesterol ratio.”

To be fair, they do go on to qualify by suggesting that NMR results may have a role in certain situations, something I am not arguing with.

I am not sure why you are continuing to argue this point when even Dr. Dayspring has said that in healthy populations, such as those in the WHS above, these lipid measures are all highly correlated:

https://www.lipid.org/newcommunity/groups/orca/topic/–2009-11-01.htm

I will agree to move off this topic and on to inflammation if you will just explain why you are continuing to assert your position even in light of the fact that the studies you are citing do not, in any way, uphold it. It would only reflect well on you to acknowledge that perhaps you overestimated the evidence on this one subject. I think people always respect an analyst who is willing to change his mind on the basis of new evidence.

I know you are busy and I respect the fact that you continue to publish my remarks. I look forward to moving on to a new topic.

Hasan, I’m not suggesting everyone get an NMR. When folks send lab results that look bad (e.g., high LDL-C, high TG, low HDL-C) I suggest an NMR because I still believe LDL-P is the best target of therapy (i.e., diet or medication).

” I’m not suggesting everyone get an NMR.”

Fair enough then but that hasn’t been the tone of the thread until now.

As for the rest, if there is evidence that treating to LDL-P could make a real difference in the health of an individual, then of course I am all for it. That said, I maintain that the real issue here is insulin resistance/ MetSyn and absent that or some other heath issue/risk marker, I am opposed to medication based on LDL-P or LDL-C alone. “Lifestyle changes” are another matter I await your thoughts on this.

Thank you again for being open enough to allow me to say my piece. I look forward to the rest of the series.

I think we are bumping up against the NC medical advice controversy again. This site has convinced me to make a personal decision about managing my health. I got the NMR (insurance happened to pay for it, but if it didn’t, no problem, $129), got a carotid ultrasound (covered), got a CAC score (not covered, $350), all with my doc saying that it was unnecessary.

For a few hundred dollars I now have more data about my health than I knew was possible a few months ago and in my individual case, more data is always better. Considering the importance of the information received, and the possible concordance issues raised here, this financial risk/information reward ratio was easily economically justifiable for me even though nothing changed, treatment wise. So my doc made the correct assumption, but she didn’t KNOW.

I know a little about risk and modeling and studies in the financial community, and know that there are a lot of prestigious, expensive and flawed theories out there. I was not shocked to find Peter pointing out a few in medical research as well.

And if you think medical professionals have theoretically strongly grounded (but different) opinions on your health, you really don’t want to know what the issues are with the theory professionals use to manage your money…

Hasan, I understand you are playing devil’s advocate here and your posts are reasoned and not inflammatory. I’m not sure that you’ve picked the best argument to advance however. Pragmatically I think the NMR test costs about $30 more than a standard Lipid profile. So what do we get for our extra money? LDL-P and other markers that could predict if you are pre diabetic.

You contend that the studies you have cited show that LDL-P provides no predictive benefit. I’ve read all of Peter’s posts and never came away with the idea that he supports NMR lipid testing for everyone. If a 20 year old male had normal Lipid profile no one would suggest he get an NNR test. If he had an abnormal lipid panel, he might benefit from an NMR test. Move our test subject to his 40’s – an age range where many males suffer heart attacks. I might convince you he could benefit from the test if he showed signs of Insulin Resistance (belly fat, elevated BP, etc). But what if he exercised and had a good height/weight ratio and no other risk factors? Can I convince you that he should get the test?

Jim Fixx the marathon runner and author died of a heart attack while running. He may be a 1 off case, but in shapetrim guys have heart attacks all the time. Could these heart attacks be prevented with an NMR test? I would think that anyone who has an actual heart attack will likely have some predictive markers that if detected could lead to treatment prior to suffering irreparable damage. There is a subset of individuals male & female that will ultimately suffer a heart attack or stroke.

Is NMR lipid testing the best and cheapest way to weed them out? Maybe, maybe not – the data Peter has provided is compelling. As he pointed out however, the signal to noise ratio of NMR lipid testing where you have a lot of patients with low risk factors is likely to show a null result. That doesn’t mean that there isn’t a signal present, only that you need a test group with greater risk factors to accentuate it.

Now if we take a step back and view things from the 40000 ft level – in the old days information transfer was pretty limited. You went to your doctor and trusted what you were told. It would take a lot of work to find relevant research and most people didn’t do it. We now have the internet age where everyone can search for most anything and find it. If you think salt and fat are bad for you – you can find lots of information to confirm your feelings. If you feel salt and fat are good for you – it may be a bit harder but you can confirm this information as well. You can do this same exercise with almost any subject.

I take everything I read on the net with a grain of salt – even what Peter writes. I do feel that he goes the extra mile to ensure what he writes is accurate and looks for contrary data that might oppose his own views. In 20 years there will almost certainly be some new test out there that is much better than NMR. But we don’t have the benefit of future findings and must do the best we can with what we have. Do doctors prescribe unwarranted tests? Of course, there is a tendency to cover their backsides and also give in to patient requests. Peter has provided the data he feels supports his arguments and it appears compelling.

There are no absolutes or guarantees in life. Steve Jobs might be alive today if he’d taken a different treatment for his cancer. He might also be just as dead, but he made a choice based on the data he had and it wasn’t the one with the best probability for the condition he had. We all have decisions to make concerning our health. If you’re rich you can have the best doctors and run every possible test. If you’re poor you generally have no money for preventative medical care. If you’re in between you make choices based on your own personal data. Since we live in a free country so if you don’t want an NMR or any other test you don’t have to get one. You may think everyone on this site is a hypochondriac or overly concerned with their health. I don’t know, but it seems to me you’re barking up the wrong tree on this one.

Peter,

“Pragmatically I think the NMR test costs about $30 more than a standard Lipid profile. So what do we get for our extra money”

You question is based on one very wrong assumption- that the cost of diagnostic testing is only represented only by the cost of the test itself and the same question could be asked about a myriad of other lab tests and diagnostic procedures. What is the cost of a PSA test after all and by that measure, there should be no controversy whatsoever about the cost of that testing.(Please see the latest Preventive Task Force recommendation on this) However, the real cost lies in the so-called “false-positives” which frequently lead to unnecessary further testing and treatment not to mention the attendant anxiety involved. In the matter discussed here, the likely further treatment is statin therapy. If routine NMR testing leads to statins, with the NNT’s I have already discussed, then the cost will be far above the $30.00 of the test. As I have tried to explain already, any screening procedure has to meet the cost/benefit criteria (using the expanded definition of cost already defined.). I see no such data for an NMR.

“There are no absolutes or guarantees in life. Steve Jobs might be alive today if he’d taken a different treatment for his cancer…….Jim Fixx the marathon runner and author died of a heart attack while running. He may be a 1 off case, but in shapetrim guys have heart attacks all the time. Could these heart attacks be prevented with an NMR test? ”

This is the argument by anecdote always used to justify screening. It may seem heartless, but there will always be people who would have been saved by a test or procedure but that simply does not justify that same test or procedure as routine screening. Otherwise we could say that every person should have every conceivable one of them. You are simply not taking into account the issue of false positives.

“Since we live in a free country so if you don’t want an NMR or any other test you don’t have to get one. You may think everyone on this site is a hypochondriac or overly concerned with their health”

I don’t think that but clearly there are a subset of people who are going to be panicked with the thought that they have undiagnosed “discordance.” There was already one person in this thread who contrary to the advice of his physician went out and obtained $500 worth of further diagnostic testing, some of which was paid by insurance and some out of pocket. The result was money wasted, some paid by the individual and some by the rest of us. (Aren’t medical costs a high enough percentage of the U.S. GDP?) To save time, before responding with the question “what if it had saved his life”, read the above again.

“So what do we get for our extra money? LDL-P and other markers that could predict if you are pre diabetic.”

We already have criteria for “pre-diabetes” and even here, an argument could be made that like “pre-hypertension”, the notion itself is just pushing more screening onto the U.S. population. However, assuming that “pre-diabetes” is a worthwhile concept, I would like to see the evidence that an NMR has demonstrable reclassification utility. In other words, does adding an NMR to the existing criteria for pre-diabetes make a significant impact on reassigning people to high or low risk groups. This is just a standard question in evaluating new testing.

“the signal to noise ratio of NMR lipid testing where you have a lot of patients with low risk factors is likely to show a null result. That doesn’t mean that there isn’t a signal present, only that you need a test group with greater risk factors to accentuate it………

Move our test subject to his 40’s – an age range where many males suffer heart attacks. I might convince you he could benefit from the test if he showed signs of Insulin Resistance (belly fat, elevated BP, etc). But what if he exercised and had a good height/weight ratio and no other risk factors? Can I convince you that he should get the test?”

If your hypothetical patient had “belly fat, elevated BP” and by “etc” you meant the additional criteria for Metabolic Syndrome, I have already said several times that this is already a situation which requires treatment or change of some kind. Before convincing me that an NMR is additionally warranted, I need to see the evidence (the kind of evidence I have already requested) that the NMR will demonstrably assist in risk classification and/or lead to a different treatment with a reasonable NNT.

You may think that I am being unnecessary quarrelsome here as you have said that you find the case for NMR and LDL-P testing “compelling.” Well, medicine is littered with compelling arguments that led nowhere or, worse, down roads we came to later regret. That is why actual evidence is the only way we have to settle arguments such as these. For those who want a more comprehensive and technical overview of the issues involved, see:

https://circ.ahajournals.org/content/119/17/2396.full#_jmp0_

We do seem to me making progress in this discussion since we already agree that not everybody needs an NMR (no routine testing). The subject now to be resolved is that in people with additional risk factors, does NMR testing add further value? I do not yet see the case for that in terms of actual evidence as opposed to theory.

I think you mean to be responding to someone else.

BTW, even a first year statics student learns that if you want improve a regression equation, look for variables that are not inter-correlated, so if you want to add a lab test for purposes of risk classification, I would suggest hs-CRP. Unlike LDL-P, CRP has been validated as adding predictive power to the set of Framingham variables:

https://circ.ahajournals.org/content/118/22/2243 (note that the author invented the test but do we want to go there???)

and conceptually makes sense since inflammation is inextricably tied up with CVD.

If you want to play around with CRP as a risk factor, there is a neat calculator here:

https://www.pramilahomeopathy.com/calc_advanced_cardiac_risk.html

which lets you compare a whole bunch of different risk assessment algorithms. (A word of caution, make sure you read the notes in order to have some understanding of each of the different algorithms before drawing any conclusions. Otherwise you might get odd results such as 0% risk.)

All that said, I don’t support using hs-CRP as another screening test (lets not talk about the JUPITER trail please!) and as a gateway to stain therapy. Rather, as noted, it has utility in improving risk classifications, reinforcing the need for lifestyle interventions, and possibly as a tool to bolster the case that higher LDL on various diets may not raising risk as much as thought (or not at all?), although this is a subject for another time.

(One additional note on CRP- since so many things can raise it, multiple measurements over time might be necessary before concluding that it is elevated. )

“I think you mean to be responding to someone else.”

Yes sorry, that was my response to David.

Had never heard Russert Trgs were so high! Hard to believe his doc did not have him on some meds to lower that! Anyone with a family history of heart disease in my view should ignore ratio’s, and caution should be exhibited in their use in any event. MY Trg to HDL ratio has always be no greater that 1:1 and yet when an NMR was done it showed very very high levels of LDL-C almost all small. Docs always said perfect numbers and no worry with family history: you exercise lots, normal weight, good BP, diet, etc.

Dr attia: you might find this interesting commentary by Dr Ron Krauss:

https://www.nxtbook.com/tristar/ada/day3_2012/index.php#/8

favors a low carb, hi fat diet, but says not only are polyunsaturated sources better than saturated fat, but goes on to say that in his studies, hi red meat intake causes all LDL particle sizes to increase, and he believes small LDL is much worse than large LDL-P and to him it sounds like size matters which is different than your and Dr.Dayspring’s viewpoint. Interesting.

Yes, interesting indeed. Ron Krauss does does really excellent work, so this is certainly worthy of further investigation.

Steve, Kraus did not say red meat causes all LDL particle SIZES to increase, he said it causes all types of LDL particle NUMBERS to increase; hence he is suggesting fat is OK as long as you limit intake of red meat. (Unfortunately that sentence was written unclearly, but that’s what he’s saying.)

I understood what Krauss said,but may not have related correctly.

Most interesting is his preference for polyunsaturates, and his statement that small LDL-P is worse than large LDL-P. Dr. Dayspring thinks otherwise, and Dr Attia has posted his view which is in line with Dr. Dayspring. With such expertise expressing an opinion, it might not be that clear, and particle size may matter. Dr Bill Davis of heartscan blog thinks small LDL-P matters more and advocates a level of carb restriction(and fat addition) to virtually eliminate them.

Would be nice to know which is it: does size of LDL-P matter or not?

In his red meat study, both exp groups ate the same lean red meat, it was only the saturated fat that changed between them and that saturated fat was made up with saturated dairy fat. With that in mind, I don’t think it’s necessarily that red meat is bad, but that red meat for breakfast lunch and dinner coupled with a high saturated fat lifestyle could be potentially atherogenic.

Palmitoleic acid: is an omega-7 monounsaturated fatty acid that is a common constituent of the glycerides of human adipose tissue It is biosynthesized from palmitic acid by the action of the enzyme delta-9 desaturase. A beneficial fatty acid, it has been shown to increase insulin sensitivity by suppressing inflammation, as well as inhibit the destruction of insulin-secreting pancreatic beta cells.[1]

https://discovermagazine.com/2012/jun/03-snake-oil-cures-for-damaged-hearts

The thing you always need to be careful of in animal studies is that they are animal studies. What works in animals doesn’t always work in humans, as we’ve got different evolutionary trajectories.

For example, hypoxia: bad for mice (or pythons); bad for humans. Cats: bad for mice; not bad for humans.

https://www.sciencemag.org/content/334/6055/528

Hello Peter,

Thank you for all the time invested in providing such important information. Do you plan to relate all this info to some dietary specifics? It would very helpful if you were able to translate this information into an action plan of sorts regarding dietary as well as exercise suggestions.

Thank you!

Peter, in the study by Asztalos referenced above, it wasn’t necessary to measure large HDL-P, because the two largest HDL’s in his scheme (alpha-1 and alpha-2) nicely blanket the size of the large HDL-P from NMR, and are therefore likely to be equivalent. So when alpha-1 and alpha-2 go up, so does large HDL-P. And I don’t think we can assume without evidence that LDL goes up when HDL goes down in these cases, although it may. That appears to an unjustified assumption from these studies, although the data should be out there somewhere, since both of these 2 studies were done on well know patient populations. Also, take a look at this study of VA-HIT patients, where Astalos uses 2D-GGE to evaluate the risk of CHD vs eight of his variables.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2194640/

Table 5 of that study shows that recurring CVD risk increases with increasing values of pre-beta-1 and alpha-3, and decreases with increasing values of the other alphas, pre-alphas, and pre-beta-2. This suggests to me that large alpha particles are strongly atheroprotective, except for alpha-3.

Please, please finish this series and if possible make some dietary recommendations – I find this subject fascinating but at times overwhelming – I need to reread segments until I understand it better. But am very personally interested, and realize that everything I keep hearing from doctors, including highly paid cardiologists, is mostly simplistic and possibly dead wrong! Thank you for making this information more available.

Dr. Attia

Thank you for this wonderful overview of key concepts in lipidology and the role of different different subtypes of cholesterol and other lipoproteins for the risk of cardiovascular disease.

I am a practicing cardiologist myself and I am always trying to improve my knowledge on the effects of diet and lifestyle interventions on the risk of cardiovascular disease. As a profesional I rely on clinical guidelines during my daily practice. But, as you are aware of, there is so much evidence suggesting that we have been on the wrong track for many years concerning diet, obesity, sugar, carbohydrate, fats and cardiovascular risk.

As a clinician I tend to go for the big questions. For example, we know that statins improve prognosis in patients with documented coronary artery disease. However, we still don´t really know whether that is due to their LDL-lowering effect or due to something else, possibly their antiinflammatory effect.

Although we know that there is a relationship between cholesterol levels, LDL-C, LDL-P and cardiovascular risk, we still don´t really know the mechanisms, or whether there is a causative relationship. Is cholesterol really a causative factor or just a surrogate. Is lowering cholesterol really as important as previously thought. We know that there are no studies showing that lowering cholesterol reduces the risk of heart disease, apart from the statin studies.

Again. Thanks for your wonderful blog. I really look forward to seeing you adress the big clinical questions;

Does lowering cholesterol by diet reduce the risk of heart disease?

What is the best way to lower cholesterol by diet?

Most clinical guidelines on the prevention of cardiovascular disease recommend staying away from saturated fat. Do you think this is an evidence based conclusion?

What is your opinion on statin therapy in primary prevention?

I have been dreaming about blogging about those big questions myself. Maybe you will get there in # 45.

Axel, there really aren’t good data on primary prevention due the time issue. Funding such studies would be very costly due to power (size) and intervention (drug).

The problem with the statin studies, of course, is that they are typically done for non-primary prevention, and they are only funded by drug companies.

What we really need is a properly done, appropriately controlled (the key) study on primary prevention.

Hi Axel:

Here is my current understanding to all your queries. If I am wrong, hopefully other commenters will correct:

Q. Does lowering cholesterol by diet reduce the risk of heart disease?

A. Current evidence appears mixed at best, depending on what cholesterol measures you use. Reducing particle count appears beneficial.

Q. What is the best way to lower cholesterol by diet?

A. A low-carb diet, such as Dr. Eric Westman’s No Sugar No Starch or Dr. Dean Ornish’s (which Peter argues is actually a low-carb diet in disguise).

Q. Most clinical guidelines on the prevention of cardiovascular disease recommend staying away from saturated fat. Do you think this is an evidence based conclusion?

A. A few months ago, I would have cited the Siri-Torino/Hu/Krauss meta-analysis from 2010 to say no, sat fat has been exonerated. However in the past few months, that paper has seemingly died an ugly death and the authors apparently no longer bother to defend it. Currently, I am not sure we have strong evidence either way. I think at this time we have to say we don’t really know.

Q. What is your opinion on statin therapy in primary prevention?

A. Currently it appears that if you are what Peter calls “discordant,” they may be useful. Likewise, if you are a man or woman who has already suffered a cardiac-type incident. If you are a woman who still has a period, there may be doubt they do much for you. As Peter says, the evidence is poor and seems mixed, maybe biased.

Welcome to the murk of uncertainty. 🙂

Another excellent post. This has been fascinating, so far. I look forward to more.

I don’t live in SD, but I live close enough I think I can get to your talk at UCSD and am planning on trying. Looking forward to hearing your speech! Along with your friend Gary Taubes, you are one of my heroes.

Hope to meet you there.

Not asking for any advice, just thought I’d share an anecdote of possibly some interest. Pre-LCHF, LDL-C was 166 (tested 5 years ago). 4 months into LCHF, LDL-C just came back at 401, TC 499. Still waiting on ApoB results before I totally freak out. One positive (yay!) is that my Trigs/HDL ratio has improved from 2.44 to 1.266.

NMR not available where I live. I’ve read that this sometimes happens to people – don’t know why other than possible ApoE problems. I’ll wait for the ApoB and ApoE and go from there. Not sure of the likelihood of it coming back particularly good. Fingers crossed it isn’t terrible.

Barry, I don’t understand why NMR is not available in your area. My understanding is only one lab in the country does the test, and your blood sample has to be sent there. You can order this test from several online services.

Hello Vernon. I do not live in your country.