Avoiding late-night snacking has long been recommended to those trying to lose weight, and this recommendation appears to be well-founded: numerous studies have found a strong correlation between eating late at night and an increased risk of obesity. Adding to this body of literature are two recently published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) which further emphasized the metabolic benefits of consuming calories earlier in the day versus closer to bedtime. So let’s take a look at how these two studies – by Vujovic et al. and by Ruddick-Collins et al., respectively – compare with each other and what they can collectively tell us about the effects of calorie distribution patterns.

Study Designs

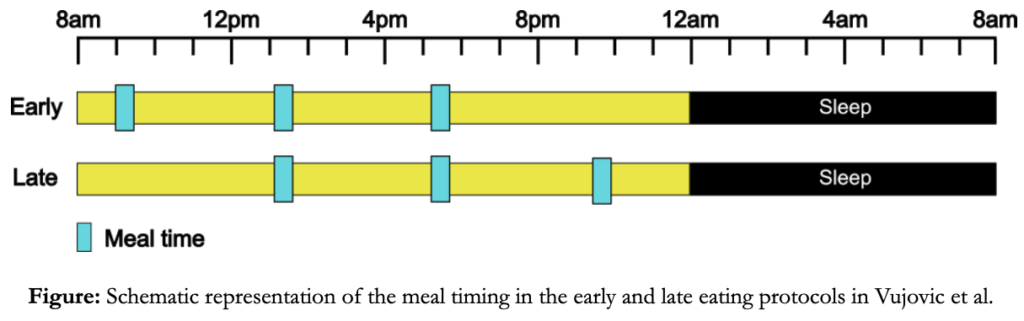

In the in-laboratory (read: highly controlled, but short and small) study by Vujovic et al., sixteen subjects with BMIs classified as overweight or obese were randomized to either an “early” or “late” eating protocol (see figure below).

After a 2-day period to allow participants to adjust to the experimental setting, they underwent four days on their randomly assigned feeding regimen. Participants then were allowed a washout interval of 3-12 weeks, after which the groups swapped and completed the other protocol. The same three isocaloric meals were consumed by both groups. On the first and last day of each feeding protocol, experimenters measured subjects’ energy expenditure (EE) and fuel utilization by indirect calorimetry over the 16-hour wake episode. On these test days, participants also self-reported their levels of hunger and appetite using visual analog scales.

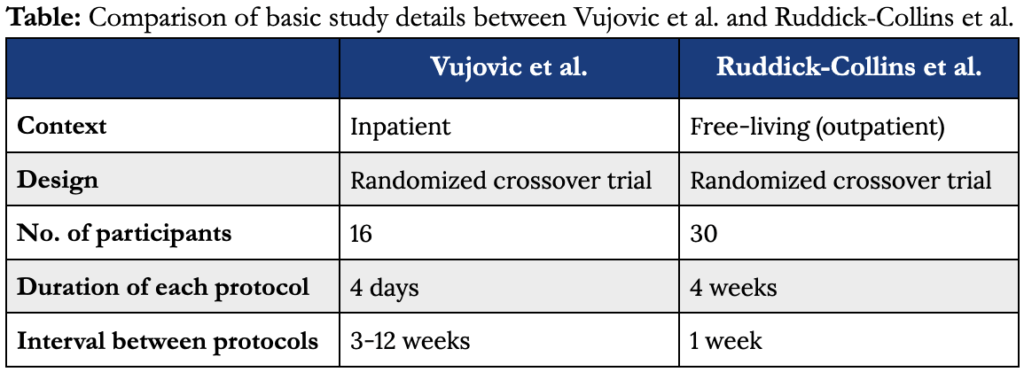

The study by Ruddick-Collins et al. recruited 30 participants, also with BMIs classified as overweight or obese. At the start of the study, each participant was randomly assigned to eat either a morning-loaded diet (“ML”: 45%, 35%, 20% calories for breakfast/lunch/dinner, respectively) or an evening-loaded diet (“EL”: 20%, 35%, 45%, B/L/D). Once participants completed four weeks of either the ML or EL protocol, they underwent a 1-week washout period before crossing over to the other arm of the study for an additional four weeks. This research group also measured perceived appetite and energy expenditure, though the latter was done using the doubly-labelled water method under free-living (out of laboratory) conditions.

A comparison of select details from both studies is presented in the table below. Note that, though both studies had fairly small cohorts, they employed a robust randomized crossover trial design, and both provided the food and beverages that the participants consumed.

Late eating increases appetite and fat storage

Both Vujovic et al. and Ruddick-Collins et al. reported that eating later in the day resulted in significantly increased self-reported ratings of hunger level relative to eating early, despite each study matching diet composition and calorie intake across protocols. Neither study reported a difference in weight changes between protocols, though this is not surprising since total caloric intake was controlled by the experimenters, and participants thus would not have been able to seek out more food in response to additional hunger.

Though subjective reports of perceived hunger and appetite used in both studies may provide some hints about metabolic effects, they are notoriously unreliable forms of measurement. One strength of the Vujovic et al. study is thus that it also assayed blood samples on test days for circulating levels of the satiety-signaling hormone leptin, which were found to provide quantitative, objective support for the differences in reported hunger. The area under the curve of leptin concentration throughout the day was elevated among early eaters relative to late eaters, which would be consistent with the participants’ reports of decreased hunger on the early protocol.

Vujovic et al. also collected biopsies of white adipose tissue to study the potential effects of late eating on adipose tissue gene expression, which was altered in a way consistent with decreased lipolysis and increased adipogenesis. Though diets were isocaloric between groups and no differences in body weight or composition would be expected over the short study duration, demonstration of a convergence of molecular and physiological changes favoring increased appetite and fat accumulation strengthens the conclusion that late eating is more likely than early eating to promote positive energy balance and development of obesity if sustained over a long period of time.

Late eating may decrease energy expenditure

Using indirect calorimetry, the Vujovic et al. team also observed significantly decreased daytime EE among those on a late-eating protocol, reporting that this group expended an average 59.4 ± 13.9 fewer kcal (5.03% less) per wake period than their early-eating counterparts, though it bears noting that this difference is near the sensitivity limit of their methodology. In contrast, Ruddick-Collins et al. – who monitored 24-hour energy expenditure via doubly-labeled water – reported no difference between EL and ML diet groups.

While this discrepancy might suggest that late eaters compensate for reduced daytime EE with elevated EE during the sleep cycle, Vujovic et al. present core body temperature (CBT) measurements which argue against that conclusion. The authors note that although EE was not measured directly during sleep periods, CBT – a proxy of resting energy expenditure – was monitored continuously. No difference was observed between groups in overnight CBT, whereas daytime CBT was significantly lower among late eaters, consistent with EE measurements by calorimetry. It’s worth noting that the authors observed a particularly strong divergence in CBT between early and late eaters in the last four hours of the sleep phase, by which point acute feeding-induced thermogenesis would be expected to have ceased in both groups. Thus, the energy expenditure difference between groups cannot be entirely explained by thermic effects of food favoring early eaters.

A more likely explanation for the apparent inconsistency in EE findings between studies lies in the details of the respective study designs. Vujovic et al’s. study involved complete shifts in meal times in early vs. late eating groups relative to sleep periods, whereas Ruddick-Collins et al.’s study involved only a shift in calorie distributions across meals, which were timed identically relative to sleep between both groups. In addition, Ruddick-Collins et al. allowed participants to choose their own mealtimes for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, potentially adding enormous variability within groups in calorie distribution relative to sleep. Finally, this team also notes that although overall calorie intake was the same between ML and EL groups, some participants were unable to consume the entire meal portions provided at the designated times – particularly for breakfast and lunch among the ML group. This means that differences in calorie distribution between protocols were likely even smaller than planned and may not have been sufficient to yield significant divergence in EE results between ML and EL diets.

Bottom Line

The results of both studies provide further evidence to support the idea that snacking close to bedtime is not a wise practice for those aiming to lose fat mass or keep it off. However, the Vujovic et al. study follows an overall stronger design and provides more robust mechanistic and quantitative data to support their findings that late eating can increase appetite and possibly reduce energy expenditure (and it’s likely the former is a greater contribution to weight gain than the latter). Still, the Ruddick-Collins et al. study, by virtue of its relatively poor control over participants’ diet patterns, manages to demonstrate that effects on appetite may be generalizable to more subtle changes in daily calorie load distribution, as well as to some level of variation in absolute meal and sleep times. It appears, in other words, that even modest shifts in calorie load toward earlier in the day would yield benefits.

In essence, these two studies offer complementary insights into the effects of late eating. The Vujovic et al. study demonstrates efficacy – how an intervention performs under ideal, highly-controlled conditions – while the Ruddick-Collins et al. study gives us an indication of effectiveness – how an intervention performs under “real-world” conditions in which individuals are able to make their own choices.

Ultimately, studies of longer duration that allow participants to modulate their total intake based on hunger level will still be important to ascertain the overall effect of early vs. late eating schedules on the development of obesity, but in the meantime, these short-term studies provide plenty of reason to think twice before grabbing a late-night snack.