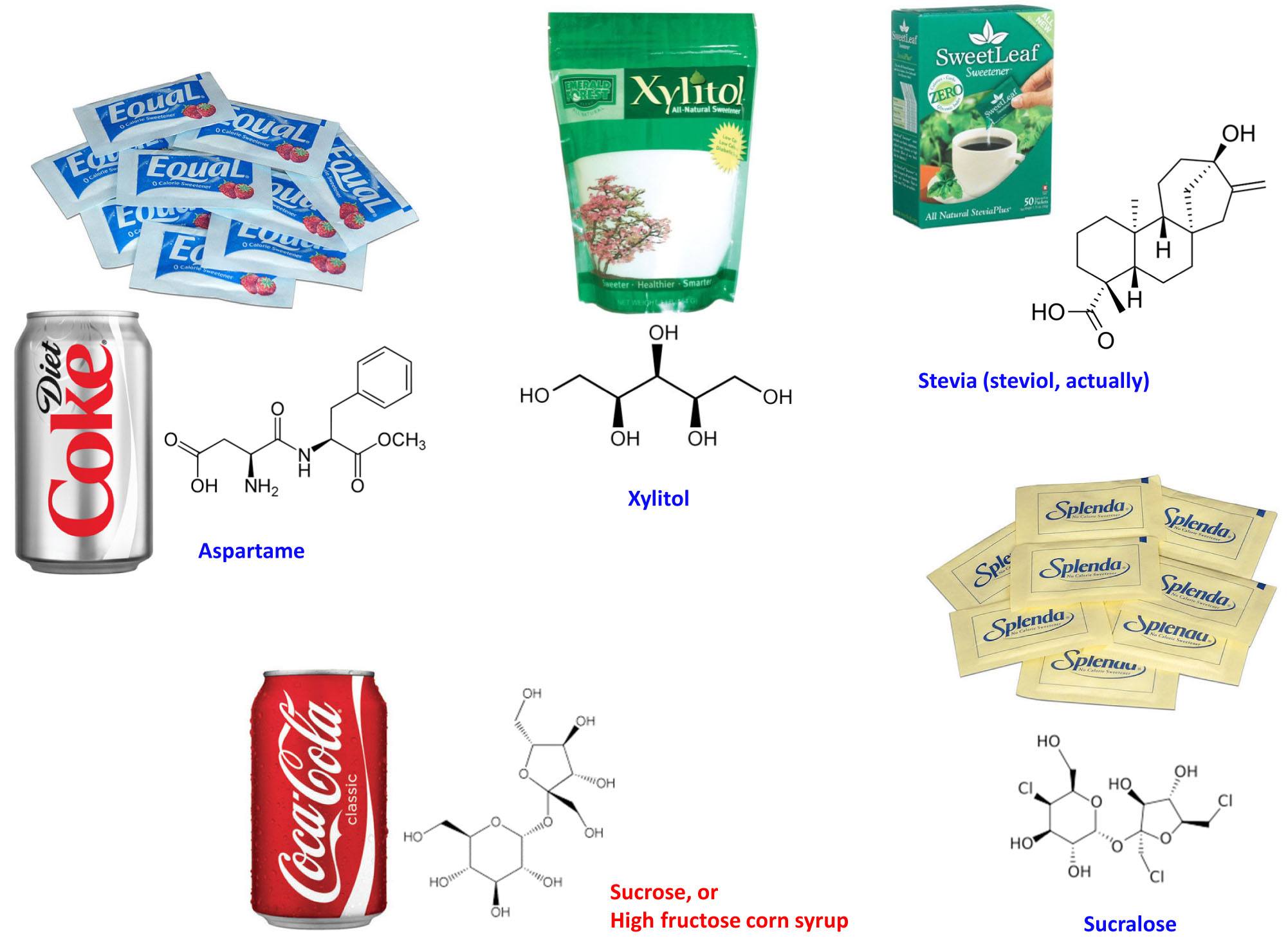

Once you realize how harmful sugar is (by sugar, of course, I mean sucrose and high fructose corn syrup or HFCS, primarily, but also the whole cast of characters out there like cane sugar, beet sugar, dextrose, corn syrup solids, and others that masquerade as sugar), you inevitably want to understand the impact of substituting non-sugar sweeteners for sugar, should you still desire a sweet taste.

Want more content like this? Check out my article on replacing sugar with allulose and my Ask Me Anything (AMA) podcast on sugar and sugar substitutes.

If you’re not yet convinced sugar is a toxin, it’s probably worth checking out my post, Sugar 101, and the accompanying lecture by Dr. Lustig. Sugar is, tragically, more prevalent in our diets today than we realize – our intake of sugar today is about 400% of what it was in 1970. And it’s not just in the “obvious” places, like candy bars and soda drinks, where sugar is showing up, either. It’s in salad dressings, pasta sauces, cereals, “healthy” sports bars and drinks, low-fat “healthy” yogurt, and most lunch meats, just to name a few places sugar sneaks into our diet.

I know some people have an aversion to aspartame (i.e., Nutrasweet, Equal) over sucrose (i.e., table sugar, sucrose, or HFCS). In other words they think Coke is “better” that Diet Coke because it uses “real” sugar instead of “fake” sugar. If you find yourself in this camp, but you’re now realizing “real” sugar is a toxin, this poses a bit of a dilemma.

There are two things I think about when considering the switch from sugar to non-sugar substitute sweeteners:

- Are non-sugar sweeteners more or less chronically harmful than sugar?

- What are the immediate metabolic impacts of consuming these products, relative to sugar?

Let’s address these questions in order.

Question 1: Are artificial (i.e., non-sugar or substitute) sweeteners more chronically harmful than sucrose/HFCS?

There’s no shortage of fear out there that consuming aspartame, sucralose, or other non-sugar substitute sweeteners will lead to chronic diseases like cancer or heart disease. However, there is no credible evidence of this in humans. One can actually make a convincing case that no substance ingested by humans has been more thoroughly tested by the FDA than aspartame. The former Commissioner of the FDA noted, “Few compounds have withstood such detailed testing and repeated, close scrutiny, and the process through which aspartame has gone should provide the public with additional confidence of its safety.” While it might be the case that you can harm a rat with aspartame, it seems you need to force the rat to eat its bodyweight in aspartame every day for a year to do so (I’m being a bit facetious, but you get the idea). In fact, even water would be harmful to us in the quantities required to render aspartame harmful if we extrapolate from rat studies.

Since its invention/discovery in 1965, there is not a single well-documented case of chronic harm to a human from ingesting aspartame, and prior to its approval for human consumption in the early 1980’s it had been studied in approximately 100 independent studies. A possible exception to this might be in the rare person with phenylketonuria (PKU). Such folks lack an enzyme required to metabolize a breakdown product of aspartame.

So, aside from the rare person with PKU, does this mean aspartame is 100% harmless? Not necessarily. 100% harmless is a pretty high bar. “Harmless,” using air travel as an analogy, is not getting on an airplane at all. Consuming aspartame is more like getting on a commercial airplane – statistically speaking you are very safe, but something bad could happen that we’re not aware of yet. Consuming sugar in the amounts we typically do, by contrast, is downright harmful. “Harmful,” by the air travel analogy, is not only getting on an airplane but skydiving with a poorly-packed parachute – you might make it, but you’re really taking a chance.

As far as other non-sugar substitute sweeteners go (e.g., sucralose, saccharin, stevia, xylitol), the same logic holds except that we don’t have quite as much data on them because most of them (see figure, below, for the most popular ones) haven’t been on our tables quite as long as aspartame. However, to date there are no data linking these substances to the diseases people tend to erroneously link them to in casual conversation.

Question 2: What are the metabolic differences between sugar and non-sugar substitute sweeteners?

The metabolic effects of table sugar (sucrose) and high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) are well understood, so I won’t review them again. If you want a quick review of sugar and why it’s probably as chronically harmful as tobacco, see my previous post on the topic. Also, Dr. Lustig and his colleagues last week published a paper in the journal Nature titled, The toxic truth about sugar, which you may want to check out if you have a subscription to Nature. The press picked this up in spades, also, and here is one such story.

So how do non-sugar substitute sweeteners compare to sucrose/HFCS in the acute or immediate metabolic phase? Most non-sugar sweeteners (e.g., aspartame, saccharin, sucralose, stevia) are much more potent in their sweetness relative to sucrose, and therefore require a fraction of the amount to give the same “sweetness” as sucrose. So for these sweeteners, only a fraction of the substance is required for equal sweetness. That’s why when you look at a can of Diet Coke it has no calories in it. The amount of aspartame that’s used is so small (given its sweetness), it doesn’t even add a calorie worth of energy. Hence, we consume a fraction of them, relative to “real” sugar to get the same sweetness.

Other non-sugar substitute sweeteners, such as alcohol sugars (e.g., xylitol, sorbitol), are not actually sweeter than sucrose, but they have very different metabolic and digestive properties. Furthermore, one actually uses similar amounts of these sweeteners, relative to sucrose (e.g., substituting an alcohol sugar in the place of sucrose occurs at about a one-to-one ratio). In other words, when consuming alcohol sugars you actually ingest non-zero calories of them. This is why you’ll note non-zero amounts of them when you look at the ingredient labels of foods containing them. Even a piece of gum sweetened with alcohol sugars contains 1 to 2 grams per piece. While an excess of alcohol sugars can cause gastrointestinal distress (e.g., if you overdo it on these you can get diarrhea), in most people they do not cause secretion of insulin from the pancreas due to their distinct chemical structure (see figure of their structures, above).

The same is true for the first group of non-sugar substitute sweeteners I mentioned (e.g., aspartame, saccharin, sucralose), with respect to the lack of insulin response. In addition to studies confirming this, I’ve also documented this in myself for xylitol (my personal favorite), aspartame (Equal), and sucralose (Splenda). I cannot speak to the other substitute non-sugar sweeteners in myself, but these three compounds seem to pass through my digestive tract without ever alerting my pancreas (i.e., without stimulating insulin). When I consume these non-sugar sweeteners neither my blood glucose nor insulin levels rise.

I should point out that some people have noted/suggested a cephalic insulin response to non-sugar substitute sweeteners. A cephalic insulin response occurs when the pancreas begins to secrete insulin before the “meal” actually gets into the bloodstream – the usual step required for the pancreas to secrete insulin. In other words, the anticipation of the meal leads to the release of insulin. This has been documented in humans, and a few studies have attempted to elucidate the mechanism indirectly by using various drugs to attempt to block this response. Furthermore, some have suggested that you can still experience the harmful effects of regular soda while consuming an equal amount of diet soda. It’s not clear to me this is true. First, this hypothesis has never been studied rigorously (i.e., prospectively and with random assignment in a controlled setting). Second, if there is some cephalic insulin response to non-sugar sweeteners, it is probably significantly less than that of sugar in both magnitude and duration, based on the studies I’ve read. To reiterate a common theme – this phenomenon is probably minimal in most people but significant in others. When I work with people who seem to be doing everything “right” but can’t seem to make improvements (e.g., fat loss), I will usually suggest removing all non-sugar substitute sweeteners to test this hypothesis.

Lastly, there has been some recent discussion about how diet soda may cause even more harm than regular soda. A few observational studies have commented on this, including a study released last week in the Journal of General Internal Medicine. Due to time and space, I’m not going to comment broadly on this paper in this post (though I will write a great deal more about this sort of study in the future). I do want to make one very important point that is true of virtually every study of this nature: it is impossible to make a correct inference without doing a prospective, random-assignment, controlled trial.

While the authors of this study acknowledge that “further study is warranted,” the lay press picks up the title of this paper: Diet soft drink consumption is associated with an increased risk of vascular events in the Northern Manhattan study, and fails to ask any questions. While I am not trying to be overly critical of the study authors (whom I do not know, either personally or by reputation), I am actually quite critical of the press that like to report on bumper-sticker messages without reading the fine print. Most people (including many policy makers, who are bombarded with this sort of bumper-sticker information) tend to form their opinions based on this sort of information.

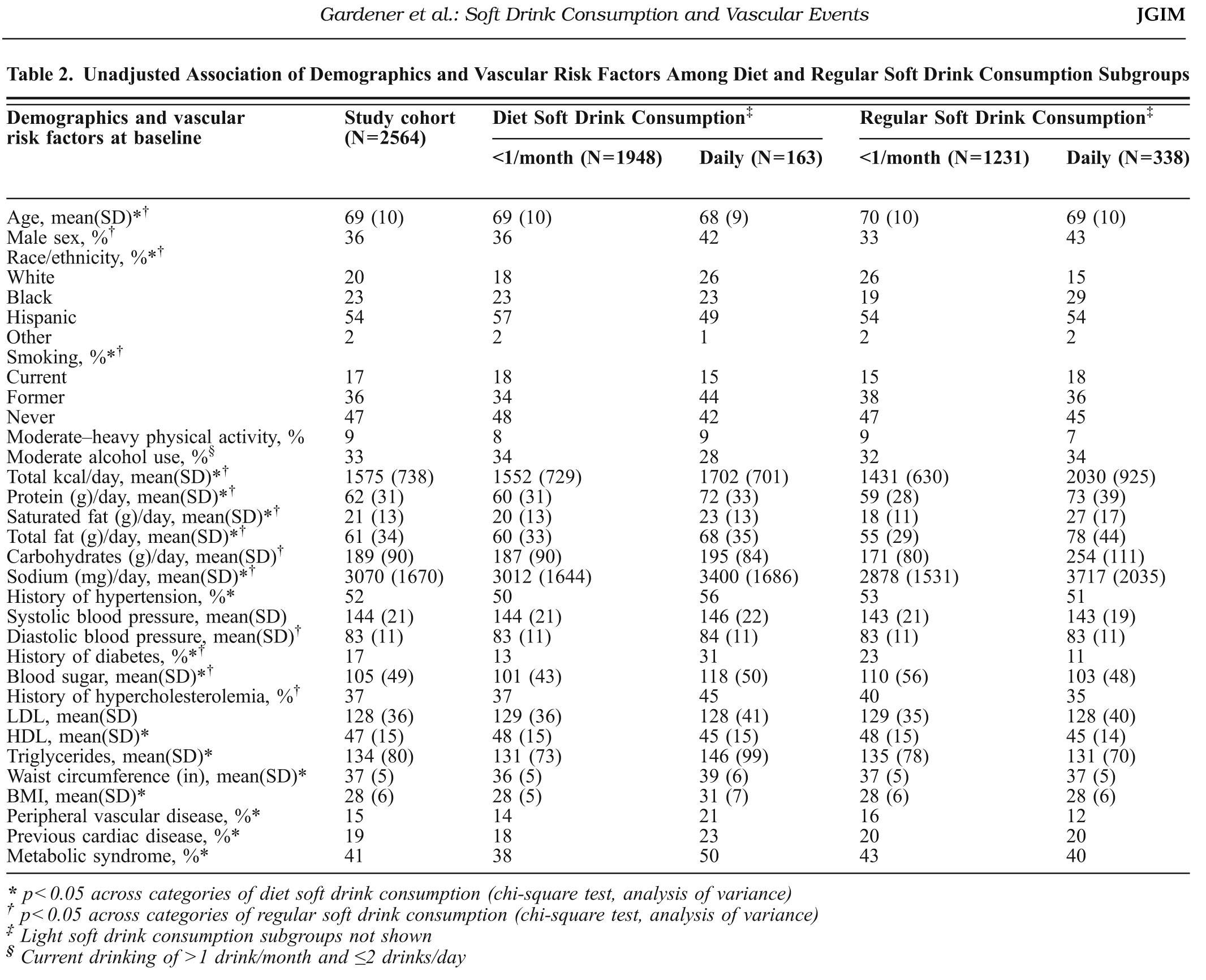

A table from this study (Table 2) is shown below. It’s a bit hard to read unless you click on it, which I’d suggest you do to see what I’m talking about. The group of 163 people who consumed diet soft drinks daily had worse clinical outcomes than the group of 1,948 people who consumed no more than 1 diet soft drink per month (all self-reported). That is, the people who drank more diet soda were more likely to have a vascular “event” (on a per person basis). Seems pretty bad, right? Is drinking diet soda actually causing this?

Well, let’s double-click on this question. Note that the people who were consuming daily diet soda (relative to those not) also had a few other factors not working in their favor including higher blood pressure, higher circulating triglycerides, a higher rate of diabetes, higher BMI, lower HDL-C, higher pre-existing vascular disease, a higher rate of metabolic syndrome, and a higher rate of previous cardiac surgery just to name a few. And in many of these factors the difference between the groups was very large (e.g., diabetes, history of peripheral vascular disease). You will also note that both groups of diet soft drink consumers reported between 1,500 and 1,700 calories per day, below the national average, suggesting yet another problem with this sort of study — self-reporting.

The authors try to correct for this obvious shortcoming by employing a statistical technique called “adjustment.” This means you try to “strip out” the differences between groups and see if the effect still holds. I do not want to turn this into a detailed post on elaborate statistics (a topic I greatly enjoy), but it’s REALLY important that you understand why this is a dangerous way to conduct science. The reason this is “dangerous” is that it only proves an association exists, not that there is any causal link between drinking diet soda and getting cardiovascular disease.

If anyone is really interested in the details of this, I actually reached out to my thesis adviser who did his Ph.D. in applied statistics at Berkeley at the age of 20 (and is one of the smartest people I’ve ever met). Just to make sure I hadn’t gone too far off the reservation, I asked him his view. Here was his response:

Do I buy the analysis? The unadjusted data (Table 2) is pretty hard to disagree with. The adjusted results are open to debate, because the conclusions depend on the form of the model that the authors proposed. A Cox proportional hazards model assumes that the predictors enter linearly into the model. This form is chosen for computational and mathematical convenience, not because anybody has a convincing argument for why the model is correct. But it’s the most popular model out there for survival analysis.

Remember also that the study is observational, not a controlled experiment. The authors can’t conclude that the diet soda is the cause of the greater disposition toward a vascular event, only that there is an association.

My translation: Taken as-is (i.e., unadjusted) there is no way to draw any conclusion from this. After statistical adjustment, you might be able to make the case that it’s worth looking into things further, but as it stands there is only an association between consuming diet soda and having a vascular event.

Want another way to think about? Think of a simple (and silly) example: I once read (I’m not making this up) that people with red cars are more likely to get into car accidents. Let’s assume this is true (though I can’t confirm it). Does it mean owning a red car causes you to have a higher chance of getting into a car accident? Or is it more likely that someone who buys a red car may drive in such way that they are more likely to have an accident? My guess is, even if this correlation between car color and accident frequency were true, there is no causal information contained within it.

Yes, it is possible the reporting of all behavior (e.g., intake) was accurate, and yes it is possible that, even when adjusting for these pre-existing differences between the groups, the outcome would have been the same. But is it likely? It is very hard for me to believe this.

There is a reason I refer (only half-jokingly) to observational epidemiology studies as “scientific weapons of mass destruction.” If you remember nothing else I write or say, please remember this: Never confuse association with causation. If we want to definitively know the answer to this question, we need to design a prospective, well-controlled, random-assignment experiment.

So what is the upshot of all of this?

I would argue (along with a legion of others) that once you eliminate sugar from your diet, your cravings for sugar actually vanish. So the question, rather than, Is it ok to consume sugar substitutes?, may actually be: Why do we need things to be sweet in the first place?

I think this is a personal choice, and something worthy of self-experimentation. I know many people who have eliminated everything sweet (both sugar and non-sugar sweeteners) from their diet, and within weeks they completely lose the desire or craving for sweet foods. Others (like me) still like the occasional taste of sweet things. One of my favorite snacks is home-made whip cream (heavy cream whipped with a touch of xylitol). But the point is this: despite occasionally consuming sugar substitutes I’ve really shed my pathologic need for sweet things. There was a day when I needed something sweet with every meal. That’s no longer true. I go days without ingesting anything sweet and don’t miss it. Other days, I feel like having some xylitol-enriched whip cream, or drinking a Diet Dr. Pepper, and I do so. Would I be better off without them? Maybe. But now we’re well past first-, second-, and third-order terms. (For a refresher on the concept of “ordered terms,” check out my post on irisin).

In summary, if you must drink a sweet beverage (or add sweetener to your coffee or tea) you are better off using a substitute for sugar than you are using sugar. But if you want to be really sure, and you want to kick the habit of needing a sweet taste, you’re probably better off avoiding substitute sweeteners altogether. If you want to be 100% safe, drink water. Just don’t make it bottled water (though that’s a whole other story). And don’t fly in airplanes or drive in cars, either.

Photo by Brooke Lark on Unsplash

I do think a third question…that you did address for your own case by direct experiment which is very cool, is whether cerebral insulin release is enough of an issue to block fat loss.

It’s a struggle for me as Im very much in the habit of drinking a lot of artificially sweetened soda.

It seems plausible. After all, insulin resistance implies a pancreas that’s extra responsive. In full blown metabolic syndrome cerebrally triggered insulin might be higher. It would just have to shut down the WAT’s energy release enough that even on a ketogenic diet, the resulting marginally greater hunger and fat intake would balance.

If you are talking about someone sipping diet soda like water all day, there would be a lot if low level insulin releases.

It may seem like a marginal issue, except for the massive sales of diet soda and the fact that I know from experience that if one assumes it must have no effect on fat loss because it has zero calories (more “calories are calories” distortion) then consumption can get pretty extreme.

It also seems plausible that the quantity and frequency may be the major issues here so sweeteners in food rather than drinks may have much less impact.

If the effect is based simply on the sweet taste and not how the sweetener is digested it’s worth knowing

Hi Peter,

What is your view on alcohol sugars such as polyols? I have reformed my diet to be low carb recently, and am eating very few carbs (fruit, a little dark chocolate and very small portions of porridge, brown rice etc.). I’m eating a lot of meat, fowl, fish, vegetables, eggs, nuts, seeds etc.

Problem is, I miss having something a bit sweet. I like to occasionally have a sweet snack. I am a young guy and am very fit (go to the gym around 5 times a week), and have a low body fat percentage. I am not changing my eating habits to lose weight, as I don’t need to lose any weight at all. I am doing it to improve my health in the long term, as before I learnt about low carb regimes, my diet cosisted almost purely of carbs (pasta, rice, cereal, bread, chips etc.). Whilst this may be manageable now, I would prefer to improve my diet now so that as I grow up i do not become very insulin resistant and get fat.

However, as i said, i still miss sweet treats. I found a website (https://www.lowcarbmegastore.com/) that sells a lot of low carb snacks, bars, sweet etc. It seems like they use technicalities to illustrate a low carb content, and it seems like a lot of there snacks are sweetened with alcohol sugars which dont have to be counted as carbs on the label.

What do you think of eating the occasional snack bar or sweet that is sweetened in this way. I know you shouldnt overdo it because of its laxative effect, but will snacks from these sort of websites be more beneficial than say a bar of chocolate from the newsagents. I wouldn’t be eating much of it at all, maybe just a little snack every now and again (would make my whole diet consist of low carb fad foods like this).

What do you think?

Cheers

I don’t think we know the “right” answer (yet). There are many issues at play — physiologic (e.g., cephalic insulin response in some, but not others) and psychological (e.g., never “losing” the taste for sweetness). It’s really quite a personal decision and one that folks should be willing to monitor within themselves. What is clear, to me at least, is that if you’re choosing between sucrose and xylitol, for example, it’s a no-brainer.

Hi Mr. Attia,

In this article, you state:

” While it might be the case that you can harm a rat with aspartame, it seems you need to force the rat to eat its bodyweight in aspartame every day for a year to do so (I’m being a bit facetious, but you get the idea). ”

However, a quick Google immediately finds studies claiming the opposite, that there was a higher frequency of cancer in rats consuming aspartame.

https://www.webmd.com/cancer/news/20051118/rat-study-shows-cancer-aspartame-link

How do you reconcile this? People ask me about aspartame all the time.

On a per weight basis, the amount of aspartame you feed a rat to harm it is significantly greater than what a human would or could eat. I’m not telling anyone it’s ok to consume aspartame, I’m just saying it’s probably a lot less harmful than sugar.

How much relevant to us is that rats endure high doses of aspartame without negative consequences? Not much, given that rats have an effective catalase metabolizing methanol in their livers and we do not: read the review by William R. Ware of While Science Sleeps, a Sweetener Kills. On the other hand we have no problem to metabolize low doses of fructose, where it is used to replenish liver glycogen (at least at breakfast time).

The note of the FDA about aspartame is an unlaughable joke.

I’ve read these user experiences with interest and would just like to add that I have tried aspartame, cyclamate, acesulfame-k, splenda (sucralose), xylitol and stevia. I had no reaction to any of them in terms of blood glucose or side effects, with the exception of some diarrhea with the xylitol, but this only happened the first couple of times I ingested it. I don’t use large amounts of any of these, just in baking, making ice-cream and desserts. I am keenly interested in any new studies that may reveal long-term negative effects, since I am not experiencing anything negative at the moment.

Hi Peter,

Thank you for your article. Can you speak to the potential effects on hunger and appetite with consumption of artificial sweeteners?

It’s probably highly variable by individual, and it hasn’t been studied (at least to my limited knowledge) robustly enough to draw unambiguous conclusions. Clearly, in some folks, artificial sweeteners are treated just like sugar (e.g., by the brain and/or pancreas), while in others, this is not the case.

Peter

A must read. From the oct.22 New Yorker, “Germs Are Us” by Michael Specter.

Among other things ,it discusses the obesity crisis in terms of certain bacterias that are no longer present in our bodies, as a result of antibiotics. antibiotics are used to fatten animals..do they fatten people?

craig

Yes, very likely based on emerging evidence that altering gut flora can impact obesity. Antibiotics almost certainly play a role, but so too does the actual food we eat.

Just read most of the comments of all you wonderful people, and am more confused then ever I was. The reason why I was searching the web was because my husband insists that he needs to drink fizzy drinks to help him to burp. He was doing fine on just using soda water made by his soda stream machine at home. Now he has gone back to drinking Coke which has Aspartame in it and I was concerned about it as he has type 2 diabetes.

My answer to all these suggestions is,,,,why don’t you all try to drink just plain water with a bit of lemon juice in it.

Stay happy and healthy and God bless you all as you seek a way to stay fit.

Or better yet, carbonated water with lemon or lime in it…

A lot of research is being conducted regarding safety aspects of stevia and actually no risk has been identified. in some cases it is dose dependent. is it correct to say that stevia is also not a safe artificial sweetener???

I would not say that.

Hi Peter

Have you read about this research?

https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/story/2013/02/15/artificial-sweetners-diet-nutrition.html

The article was confusing to me. No insulin release is good. Why would they find that it is bad? More confusing info from the main stream media. I think their correlation is wrong; Obese people drink diet soda to avoid a few calories here and there. Diet soda doesn’t make them obese. Thoughts?

You hit the nail on the head. These are real associations, no doubt. But it’s quite likely the arrow of causation is going the other way. There certainly may be problems with diet soda (I drink at most 1 per month, and usually less), but I have a hard time imagining that ounce for ounce, diet soda is half has harmful as regular soda.

Peter,

Very interesting article, and I’m impressed with the depth of knowledge shown by the commenters.

However, I do not agree that aspartame is “Safe”. Your reliance on the stamp of approval by the FDA does nothing to assuage my doubts. The FDA has an extremely poor record when it comes to the safety of drugs and products it approves. In my opinion, and I am not alone, is that the FDA is the most corrupt and incompetent agency of the US government.

Aspartame breaks down into methanol and formaldehyde inside the human body. Does anyone here think that’s healthy? There was an incident 10-15 years ago, widely reported at the time, concerning an airline pilot who collapsed during a passenger stop. He was taken to a hospital, but the doctors couldn’t figure what was wrong until someone said he consumed several diet sodas daily, sometimes 2-4 during a flight. He had aspartame poisoning!

Further, do you realize that diet sodas sweetened with aspartame have an expiration date? The aspartame gradually breaks down into methanol after a month or two, depending on ambient temperatures. I’ve tried an expired one, just to see how it tasted – it was disgusting!

Thanks, Peter. I will be a regular reader from now on.

Roger

Roger, well I certainly agree that aspartame tastes horrible! I think the question is still one of dose. If there is toxicity at “normal doses” of aspartame, it must be small, lest we’d be seeing more of it. Great data do exist on consumption. Anecdotes aside, clearly the safest thing to do is avoid it, but if I was forced to choose between a diet coke and regular coke….I’d drink the diet coke. I’d prefer soda water with lime to either, though.

Hi Peter! New reader to your blog, fascinating stuff. I’m curious about this way of nutrition in regards to child development and wondering if you have any thoughts/data/research on how/what to feed growing children? Any ideas on the most favorable sugar substitute for them (in terms of health not taste)? Many many thanks! 🙂

See post about my daughter.

Being overweight may be unattractive in the opinion of society but it doesn’t mean the perfect picture of unhealthy. Diabetes is one of the main reasons people get scared into “healthy” eating and exercise. The reason overweight people have a higher risk of diabetes is because they eat more diet foods to let’s face it appear more attractive. Eat sugary foods with aspartame and I guarantee you will have diabetes in a short period of time. The reason people can’t see the harmful connection is that the new generation never had a chance to know what good food tastes like. Remember, greed isn’t just about money. You can be greedy for wisdom.

Hi Peter!

Thank you for this posting. I always appreciate your willingness to stay away from dogmatism and your guarded approach to interpreting the evidence.

My question is regarding sweeteners (including Low GI sugar alcohols like xylitol and erythritol) and ketones. dietdoctor.com has a very interesting post concerning sweeteners. After consuming a Pepsi Max Dr. Eenfeldt monitored both his blood sugar and his ketones. He observed no significant movement in his blood sugar levels but did observe a very significant decrease in his blood ketone levels.

I have also read some other studies that observed similar phenomenon with xylitol. Is is possible that sugar substitutes for some reason unrelated to insulin and blood sugar can have a depreciable effect on blood ketones? Could this also explain why many people have experienced weight loss problems they have attributed to sweeteners?

Here is the link if you have not read his post: https://www.dietdoctor.com/is-pepsi-max-bad-for-your-weight

Thanks for sharing, Joe. Had no read this. The effect could be mediated by a cephalic insulin response or some other impact on hepatic glucose output, I suppose?

Dr. Attia,

I was wondering if there are data regarding insulin response to diet soda. I am admitting a diet dr. pepper fan.

Short answer, is aspartame should not raise insulin, but it might, as I explain in this post.

That was what I gathered with the pre-prandial pancreatic response to food stimulus. I really don’t want to give it up and am hoping it doesn’t affect metabolism. Thank you for your response.

Probably the best thing to do, Cynthia, is a self-experiment. If you’re stalled in some way, see what happens if you sub sparkling water for Diet Dr. P for 4-8 weeks.

About 10 years ago I used to be very addicted to Diet Coke– drinking 4-5 32oz buckets/day. I just wanted it all the time. Eventually I started having issues where I was throwing up very often (with no other side-effects), with some random acute pain like an ulcer. A doctor told me he thought it was the aspartame and that I should quit diet sodas immediately. I did. No more stomach issues, ever again. Could be a coincidence, or some other cause, but I’ve been hesitant since to consume anything with aspartame. I’ve tried Splenda in things, but it has a sickly-sweet-chemical taste that I just can’t get past. I have had really good luck with the xylitol, though. But now that I’ve been in ketosis for about a month, I rarely crave things that would require it.

Hi Peter

I’ve only just discovered your blog and could spend hours here! It’s wonderful informative and well researched.

I thought you may be interest in a program that aired in Australia last Thursday on ABC’s Catalyst program on Saturated Fat and Cholesterol and how we’ve all been fed a lie for decades!

https://www.abc.net.au/catalyst/stories/3876219.htm

Part II will be airing this Thursday night. I have no associated with the ABC or this program but as one interested in optimal health and nutrition, thought you might find it of value.

In Good Health!

Suzie.

Very interesting. Thanks for sharing.

Peter, your response to “Wally” on 22 Apr 2012 seems to imply that you do not believe that sucralose induced gut dysbiosis is relevant to fat accumulation. However, on 27 Nov 2012 you state that there is emerging evidence to support the concept of gut flora being relevant to obesity. Have I misunderstood your initial take or was there a change of heart over those months?

Personally, I feel better without any artificially created sweeteners in general, and lots of water. But I must be one of the cephalicly challeged individuals with regard to insulin response because when I’m in ketosis, any sweeteners at all, even the natural ones, leave me foggy for 30 to 60 minutes or so.

I guess my question is, is your general stance that we should choose the lesser of the evils presented? As with the grass fed vs grain fed beef debate? Also, do you feel that, realistically, the potential dysbiosis from sucralose is enough to negate the impacts of an improved and sugar/carbohydrate restricted diet?

I’m inclined to believe that with a high quality pro/prebiotic, and healthy choices in the rest of the diet, the impact of sucralose would be minimal, and most people would see positive gut flora changes anyway. Maybe I’m just making random statements. And anyway, the study I have only documents the dysbiosis in male rats.

The latter. I think my understanding of nutrition continues to evolve daily.

During the blog a comment was made that there have been no accounts of toxicity from aspartame and other artificial sweeteners. This is not an accurate comment. There have been tens of thousands of reported accounts of toxicity. The chemical reaction occurring from digestion produces formaldahyde and has been advertised in dozens of articles and is medically accepted. During 1995 the FDA stops taking accounts of adverse reactions to aspartin after 75% of there total complaints were related to cases of aspartame toxicity. The FDA has recieved dockets for the removal of aspartame as a neurotoxic drug.

However I don’t believe chemical sweeteners and natural sweeteners like stevia are in the same boat.

I knew that sugar & Aspartame have their side effects. But didn’t knew that Stevia is also harmful.

In this notion I thought that Coca Cola which uses stevia is also better that HFCS. But also my doubts got cleared after I read this article. https://5best.in/shocking-facts-about-coca-cola/