Author’s note: This post was originally published in May, 2014. It has been updated to reflect my current thinking on the topic. Perhaps the best addition, by popular demand, is Rik’s coffee recipe (click the 1st inline footnote).

§

In 2012, I was having dinner with a good friend, Rik Ganju, who is one of the smartest people I know. And one of the most talented, too—a brilliant engineer, a savant-like jazz musician, a comedic writer, and he makes the best coffee I’ve ever had.1Here is the coffee recipe, courtesy Rik. I make this often and the typical response is, “Why are you not making this for a living?” Look for Vietnamese cinnamon, also known as Saigon cinnamon; you need two big dashes, if that. You need real vanilla (be careful to avoid the cheap versions with added sugar). Best is dissolved in ethanol; if that doesn’t work for you get the dried stick and scrape the pods. Then find a spice store and get chicory root (I’m a bit lazy and get mine on Amazon). You’ll want to replace coffee beans with ~10% chicory on a dry weight basis. If you’re on a budget, cut your coffee with Trader Joe’s organic Bolivian. But do use at least 50% of your favorite coffee by dry weight: 50-40-10 (50% your favorite, 40% TJ Bolivian, 10% other ingredients [chicory root, cinnamon, vanilla, amaretto for an evening coffee]) would be a good mix to start. Let it sit in a French press for 6 minutes then drink straight or with cream, but very little–max is 1 tablespoon of cream. The Rik original was done with “Ether” from Philz as the base. I was whining to him about my frustration with what I perceived to be a lack of scientific literacy among people from whom I “expected more.” Why was it, I asked, that a reporter at a top-flight newspaper couldn’t understand the limitations of a study he was reporting on? Are they trying to deliberately mislead people, or do they really think this study which showed an association between such-and-such, somehow implies X?

Rik just looked at me, kind of smiled, and asked the question in another way. “Peter, give me one good reason why scientific process, rigorous logic, and rational thought should be innate to our species?” I didn’t have an answer. So as I proceeded to eat my curry, Rik expanded on this idea. He offered two theses. One, the human brain is oriented to pleasure ahead of logic and reason; two, the human brain is oriented to imitation ahead of logic and reason. What follows is my attempt to reiterate the ideas we discussed that night, focusing on the second of Rik’s postulates—namely, that our brains are oriented to imitate rather than to reason from first principles or think scientifically.

One point before jumping in: This post is not meant to be disparaging to those who don’t think scientifically. Rather, it’s meant to offer a plausible explanation. If for no other reason, it’s a way for me to capture an important lesson I need to remember in my own journey of life. I’m positive some will find a way to be offended by this, which is rarely my intention in writing, but nevertheless I think there is something to learn in telling this story.

The evolution of thinking

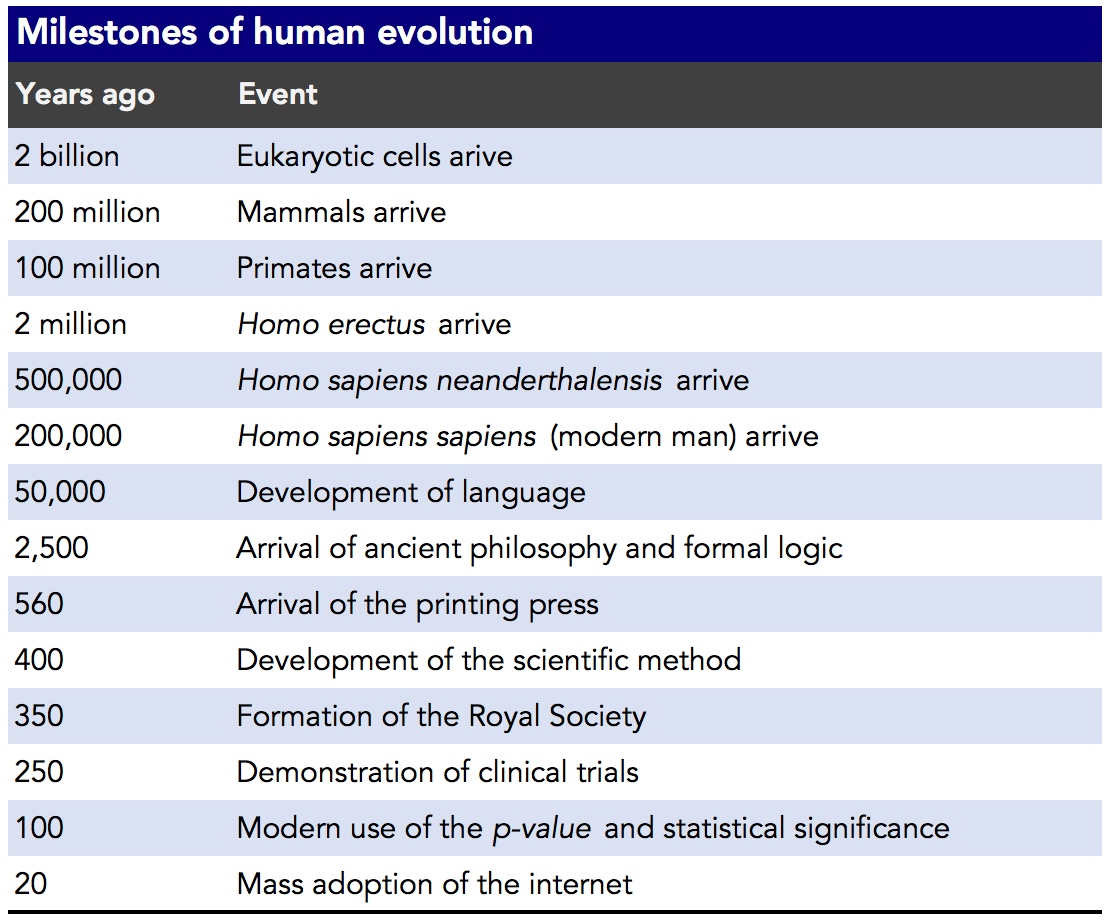

Two billion years ago, we were just cells acquiring a nucleus. A good first step, I suppose. Two million years ago, we left the trees for caves. Two hundred thousand years ago we became modern man. No one can say exactly when language arrived, because its arrival left no artifacts, but the best available science suggests it showed up about 50,000 years ago.

I wanted to plot the major milestones, below, on a graph. But even using a log scale, it’s almost unreadable. The information is easier to see in this table:

Formal logic arrived with Aristotle 2,500 years ago; the scientific method was pioneered by Francis Bacon 400 years ago. Shortly following the codification of the scientific method—which defined exactly what “good” science meant—the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge was formed. So, not only did we know what “good” science was, but we had an organization that expanded the application, including peer review, and existed to continually ask the question, “Is this good science?”

While the Old Testament makes references to the earliest clinical trial—observing what happened to those who did or did not partake of the “King’s meat”—the process was codified further by 1025 AD in The Canon of Medicine, and formalized in the 18th century by James Lind, the Scottish physician who discovered, using randomization between groups, the curative properties of oranges and lemons—vitamin C, actually—in treating sailors with scurvy. Hence the expression, “Limey.”

The concept of statistical significance is barely 100 years old, thanks to Ronald Fisher, the British statistician who popularized the use of the p-value and proposed the limits of chance versus significance.

The art of imitation

Consider that for 2 million years we have been evolving—making decisions, surviving, and interacting—but for only the last 2,500 years (0.125% of that time) have we had “access” to formal logic, and for only 400 years (0.02% of that time) have we had “access” to scientific reason and understanding of scientific methodologies.

Whatever a person was doing before modern science—however clever it may have been—it wasn’t actually science. And along the same vein, how many people were practicing logical thinking before logic itself was invented? Perhaps some were doing so prior to Aristotle, but certainly it was rare compared to the time following its codification.

Options for problem-solving are limited to the tools available. The arrival of logic was a major tool. So, too, was the arrival of the scientific method, clinical trials, and statistical analyses. Yet for the first 99.98% of our existence on this planet as humans—literally—we had to rely on other options—other tools, if you will — for solving problems and making decisions.

So what were they?

We can make educated guesses. If it’s 3,000 BC and your tribemate Ugg never gets sick, all you can do to try to not get sick is hang out where he hangs out, wear similar colors, drink from the same well—replicate his every move. You are not going to figure out anything from first principles because that isn’t an option, any more than traveling by jet across the Pacific Ocean was an option. Nothing is an option until it has been invented.

So we’ve had millions of years to evolve and refine the practice of:

Step 1: Identify a positive trait (e.g., access to food, access to mates),

Step 2: Mimic the behaviors of those possessing the trait(s),

Step 3: Repeat.

Yet, we’ve only had a minute fraction of that time to learn how to apply formal logic and scientific reason to our decision making and problem solving. In other words, evolution has hardwired us to be followers, copycats if you will, so we must go very far out of our way to unlearn those inborn (and highly refined) instincts to think logically and scientifically.

Recently, neuroscientists (thanks to the advent of functional MRI, or fMRI) have been asking questions about the impact of independent thinking (something I think we would all agree is “healthy”) on brain activity. I think this body of research is still in its infancy, but the results are suggestive, if not somewhat provocative.

To quote the authors of this work, “if social conformity resulted from conscious decision-making, this would be associated with functional changes in prefrontal cortex, whereas if social conformity was more perceptually based, then activity changes would be seen in occipital and parietal regions.” Their study suggested that non-conformity produced an associated “pain of independence.” In the study-subjects the amygdala became most active in times of non-conformity, suggesting that non-conformity—doing exactly what we didn’t evolve to do—produced emotional distress.

From an evolutionary perspective, of course, this makes sense. I don’t know enough neuroscience to agree with their suggestion that this phenomenon should be titled the “pain of independence,” but the “emotional discomfort” from being different—i.e., not following or conforming—seems to be evolutionarily embedded in our brains.

Good solid thinking is really hard to do as you no doubt realize. How much easier is it to economize on all this and just “copy & paste” what seemingly successful people are doing? Furthermore, we may be wired to experience emotional distress when we don’t copy our neighbor! And while there may have been only 2 or 3 Ugg’s in our tribe 5,000 years ago, as our societies evolved, so too did the number of potential Ugg’s (those worth mimicking). This would be great (more potential good examples to mirror), if we were naturally good at thinking logically and scientifically, but we’ve already established that’s not the case. Amplifying this problem even further, the explosion of mass media has made it virtually, if not entirely, impossible to identify those truly worth mimicking versus those who are charlatans, or simply lucky. Maybe it’s not so surprising the one group of people we’d all hope could think critically—politicians—seems to be as useless at it as the rest of us.

So we have two problems:

- We are not genetically equipped to think logically or scientifically; such thinking is a very recent tool of our species that must be learned and, with great effort, “overwritten.” Furthermore, it’s likely that we are programmed to identify and replicate the behavior of others, rather than think independently, and independent thought may actually cause emotional distress.

- The signal (truly valuable behaviors worth mimicking)-to-noise (all unworthy behaviors) ratio is so low—virtually zero—today that the folks who have not been able to “overwrite” their genetic tendency for problem-solving are doomed to confusion and likely poor decision making.

As I alluded to at the outset of this post, I find myself getting frustrated, often, at the lack of scientific literacy and independent, critical thought in the media and in the public arena more broadly. But, is this any different than being upset that Monarch butterflies are black and orange rather than yellow and red? Marcus Aurelius reminds us that you must not be surprised by buffoonery from buffoons, “You might as well resent a fig tree for secreting juice.”

While I’m not at all suggesting people unable to think scientifically or logically are buffoons, I am suggesting that expecting this kind of thinking as the default behavior from people is tantamount to expecting rhinoceroses not to charge or dogs not to bark—sure it can be taught with great patience and pain, but it won’t be easy in short time.

Furthermore, I am not suggesting that anyone who disagrees with my views or my interpretations of data frustrates me. I have countless interactions with folks whom I respect greatly but who interpret data differently from me. This is not the point I am making, and these are not the experiences that frustrate me. Healthy debate is a wonderful contributor to scientific advancement. Blogging probably isn’t. My point is that critical thought, logical analysis, and an understanding of the scientific method are completely foreign to us, and if we want to possess these skills, it requires deliberate action and time.

What can we do about it?

I’ve suggested that we aren’t wired to be good critical thinkers, and that this poses problems when it comes to our modern lives. The just-follow-your-peers-or-the-media-or-whatever-seems-to-work approach simply isn’t good enough anymore.

But is there a way to overcome this?

I don’t have a “global” (i.e., how to fix the world) solution for this problem, but the “local” (i.e., individual) solution is quite simple provided one feature is in place: a desire to learn. I consider myself scientifically literate. Sure, I may never become one-tenth a Richard Feynman, but I “get it” when it comes to understanding the scientific method, logic, and reason. Why? I certainly wasn’t born this way. Nor did medical school do a particularly great job of teaching it. I was, however, very lucky to be mentored by a brilliant scientist, Steve Rosenberg, both in medical school and during my post-doctoral fellowship. Whatever I have learned about thinking scientifically I learned from him initially, and eventually from many other influential thinkers. And I’m still learning, obviously. In other words, I was mentored in this way of thinking just as every other person I know who thinks this way was also mentored. One of my favorite questions when I’m talking with (good) scientists is to ask them who mentored them in their evolution of critical thinking.

Relevant aside: Take a few minutes to watch Feynman at his finest in this video—the entire video is remarkable, especially the point about “proof,”—but the first minute is priceless and a spot on explanation of how experimental science should work.

You may ask, is learning to think critically any different than learning to play an instrument? Learning a new language? Learning to be mindful? Learning a physical skill like tennis? I don’t think so. Sure, some folks may be predisposed to be better than others, even with equal training, but virtually anyone can get “good enough” at a skill if they want to put the effort in. The reason I can’t play golf is because I don’t want to, not because I lack some ability to learn it.

If you’re reading this, and you’re saying to yourself that you want to increase your mastery of critical thinking, I promise you this much—you can do it if you’re willing to do the following:

- Start reading (see starter list, below).

- Whenever confronted with a piece of media claiming to report on a scientific finding, read both the actual study and the media, in that order. See if you can spot the mistakes in reporting.

- Find other like-minded folks to discuss scientific studies. I’m sure you’re rolling your eyes at the idea of a “journal club,” but it doesn’t need to be that formal at all (though years of formal weekly journal clubs did teach me a lot). You just need a good group of peers who share your appetite for sharpening their critical thinking skills. In fact, we have a regularly occurring journal club on this site (starting in January, 2018).

I look forward to seeing the comments on this post, as I suspect many of you will have excellent suggestions for reading materials for those of us who want to get better in our critical thinking and reasoning. I’ll start the list with a few of my favorites, in no particular order:

- Anything by Richard Feynman (In college and med school, I would not date a girl unless she agreed to read “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman”)

- The Transformed Cell, by Steve Rosenberg

- Anything by Karl Popper

- Anything by Frederic Bastiat

- Bad Science, by Gary Taubes

- The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, by Thomas Kuhn

- Risk, Chance, and Causation, by Michael Bracken

- Mistakes Were Made (but not by me), by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson

- Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman

- “The Method of Multiple Working Hypotheses,” by T.C. Chamberlin

I’m looking forward to other recommendations.

Ah, this is such an excellent post, relevant to so much more than just nutrition.

Obviously this quote comes to mind: “Science is a way of thinking much more than it is a body of knowledge.” -Carl Sagan.

All this reminds me of an online course I recently took, called Food for Thought. It’s taught by three McGill profs and is offered through edX (https://www.mooc-list.com/course/chem181x-food-thought-edx). It covers the basics of nutrition, spanning from micronutrients, to macronutrients, food additives, agriculture, weight control and everything in between. It’s very comprehensive but presents the information in a way that’s accessible to the general learned public. One of the things I really appreciated was learning about scientific publications- their history, how they work and how to interpret them. For every study that says “white”, there is another equally reputable saying “black”. One must also be aware of some important factors that put the findings in context, notably dosage and exposure. That is, chemical “A” may be dangerous at high doses when administered to rats, but do humans have nearly the same amount of exposure, and if they do, will it have an affect on them? (After all, humans are not rats.)

So, lots of great stuff in this course. Perhaps there are some questionable assertions in some parts (mostly regarding agricultural methods), but at least the course teaches you to think critically and so not to take anything at face value.

Once again, great job on this post. Thank you and keep it up! I look forward to reading more from you.

Great quote by Sagan! Thanks for sharing. I think it addresses concerns put forth by others.

Think of it from another perspective: We are all hard-wired to imitate. When we are offered mentors to imitate who are critical thinkers, we become critical thinkers. Most people are not offered such mentors, not at home, not in school, and not in college. When elementary school barely teaches science (in schools of poor children science is often cut in favor of the three ‘r’s) and what it does teach is only that which is already agreed to be absolute, then children are not exposed to the give and take of science exploration, that a large portion of hypotheses turn out to be imprecise or false. The public’s view of science is that created in school, that science knows everything absolutely. Then the press etc. present the vagaries of real science, and the public just shrugs shoulders and gives up or takes sides.

Another example: If you would have also been offered mentors who taught a mystical approach to life, you might have imitated them and thought mystically in addition to scientifically. Steve Jobs imitated rebels and critical thinkers and created his brilliant products and designs, and he imitated quackery health presenters and died young of delayed treatment of his cancer. Not that combining disciplines has to lead to this.

Yup, certainly puts into perspective the role of luck. Feynman would be the first to acknowledge the role his father played in developing curiosity in him.

And Neil DeGrasse Tyson’s mother just spoke about the role she played in raising him: https://www.wnyc.org/radio/#/ondemand/369021

For not being a neuroscientist, you do a great job of consolidating a lot of key points here! I especially like your focus on learning and practice as a way of overcoming our more basic cognitive tendencies (like imitation). I have no evidence of this, but I suspect that our current culture exacerbates the problem of science literacy by training our brains in the exact opposite way we’d want them trained if we were going to focus on critical thinking. This starts early on in schools, which now focus on (and reward) teaching kids to excel on standardized tests rather than thinking critically. It continues well into adulthood given so many aspects of our modern life focus on relatively immediate rather than long-term rewards (video games, TV, email, finding information at any time of day online, etc.). Our opportunities for practicing critical thinking skills (weighing the benefits of short vs. long term rewards, seeing both sides of an issue, anticipating outcomes, etc.) are becoming few and far between, unless we are the lucky few who are born with an abundance of curiosity (and/or have our curiosity encouraged from an early age). I also suspect our growing dependence on sugar has a role in this process by weakening our prefrontal cortex and its ability to regulate our more basic reward system (in a similar way that alcohol and drug addicts’ reward systems take over their ability to think critically). And that’s not even taking into account the damage high levels of dietary sugar likely does to the brain in general! I’m more than a little concerned we won’t see many improvements in get in teaching more people to think scientifically without some major policy changes in education, health, and nutrition.

50000 Development of language

…

2500 arrival of ancient philosophy and formal logic

…

You forgot *writing*! People could much more easily transform information from generation to generation. Maybe 5500 or so years ago in Mesopotamia and Egypt. Surely it helped those Greek philosophers in the end, and helped in this boom of culture, etc. 🙂

Fair point. Doesn’t change my thesis, though.

As a computer programmer, I’ve always felt that logic is the solution to any problem. But as I get older, I realize that solving the problem of how to get people thinking for themselves is much more difficult than it seems at face value. Half the time, people don’t understand the difference between good and bad data, and the other half of the time, people are contrarian for the sake of contrarianism. It hits on a quote you mentioned in another post by Bastiat:

“We must admit that our opponents in this argument have a marked advantage over us. They need only a few words to set forth a half-truth; whereas, in order to show that it is a half-truth, we have to resort to long and arid dissertations”

The trouble is that most topics are so enormously complicated, that people might extract a small component of it, ignore crucial details, and make faulty conclusions (ie Butter has fat in it, body fat is bad, therefore don’t eat butter). The more complicated components, the more likely people are to build faulty logic. It’s hard to understand why hormones have an impact on fat storage, just like it’s hard to understand why measles immunization is not going to stimulate inflammation in your gut and give you autism.

Simultaneously, any topic that takes more than 45 seconds to explain is ignored by mainstream media, which amplifies public ignorance about most topics.

Also, in order to be open minded about anything, one has to navigate through the world with a presupposition they might be wrong. As it turns out, people are not particularly good at doing this, especially when new information is coming from a person who they do not know or respect. Even if a person gets good information, it’s likely to fall on the floor.

All very depressing, but likely correct.

We all have the answer within us….. Historically we did not have a TV, radio or light after dark. I believe that many people turned to meditation and intuition to gain the knowledge of proper eating. For my healing jerney I used intuition and questioned all the food and the science and each time I got the correct answer. A clear yes or no to every study and every morsel of food to enter my body.

I’m very excited about this blog. I got a reading list for at least this summer. 🙂

As a non-scientist I only have the little bit to offer I learned in my college philosphy classes. The biggest gem to me: Plato’s cave story. If you don’t see the truth you can’t reach for it.

In the meantime I’m eagerly waiting on the blog post on insulin- resistance. Going low-carb (to the point of measuring blood sugar after every food) has helped with insulin-resistance of my muscles (I’m increasing muscle mass and losing body fat), but seemingly not insulin-resistance of the liver, which still dumps too much glucose into my blood in the morning when cortisol goes up. Will I always have to exercise hard when this happens or is there hope that my liver will get more insulin-sensitive?

Thanks for all your wonderful blogs that help me get through the science I missed in college.

Birgit

I’m working on it…

Birgit,

Have you considered the effect of gluconeogenesis on your blood glucose level as you sleep? I think it’s a fairly common phenomenon among humans that blood glucose is high in the morning.

Birgit,

“Dawn phenomenon” is often caused by eating too much protein in the evening. Try reducing your dinner protein portion and eating more protein at lunch instead. 😉 This has worked for many women.

I have a couple of thoughts on this interesting post:

1. I believe science has been around a lot longer than 400 years or so. If you take into consideration the practice of herbs and other natural remedies you would find that shamans/medicine men, etc. who used these remedies did so based on predictability, repeatable results and standard dosages. Isn’t this science?

2. In the late 1960s Candace Pert, PhD, presented the idea that the “mind” isn’t located only in the head/brain, but rather throughout the body. Over the decades this has led to some fascinating leaps in scientific (not the mainstream) thinking. People like her as well as many others (Robbie Richardson, PhD, Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD, Carl Simington, MD, et al) have discovered that the this interplay between mind and the physical self is closer to the Eastern paradigm than the Western one that is modeled on the Cartesian philosophy. Thus, we see the interplay between emotions and physical health (visa vis neurotransmitters) as well as between mental states and emotions. For example, certain ways of thinking lead to stress which may lead to emotional and/or physical problems (depression, ulcers, inflammation, cardiac illness, etc). A good number of neuroscientists and biologists have discovered the value of meditative practice in reducing not only stress but also increasing grey matter. Logic, therefore, tends to be a bit overrated in the overall picture because it is a conscious activity and so much of what is creating and affecting states of health is actually subconscious. And if you read Sam Harris’s latest work on free will, then it seems that more important than conscious thought is what’s going on beneath the surface.

In the interest of brevity, and I’ve already taken up enough space here, by branching out into the study of contemplative practices it becomes apparent that one of the biggest stumbling blocks is the misunderstanding of what “mind” actually is. Our study of the mind in the West is very limited, while the study of how the mind works, reacts and changes is much better understood by, say, the Buddhists who have been at it for 2500 years or so.

Observation has been around forever. Sharing has been around forever. But with modern science you have a high standard – to write and publish a methods and materials section that is absolutely transparent about what’s being done. This is a requirement which I believe the shaman did not have to live up to (btw- i have respect for these people, and I’m not suggesting they avoided transparency about methods). And the results must be reproducible by your peers or anyone with access to the materials, not just by one blessed shaman. There was a turn towards radical transparency in the 1660s that was needed before one paper could build open another in a solid way. I have respect for those older traditions and not enough knowledge about how they dealt with transparency and reproducibility in their ecologies – just pointing out some distinctions that first come to mind.

I’m trying not to be rude but you need to look up the scientific method and critical thinking e.g. The study of herbs and their benefits was essentially irrelevant before the scientific method. Even after that actually – if you can’t test a persons blood, what scientific results could you really provide. Sure you might give horny goat weed to 10 people and have them all increase their libido and assume by extension testosterone but what if horny goat weed only grew in summer when lots of people naturally have higher testosterone or maybe it decreased estrogen?

I strongly recommend looking up the differce between correlation and causation. You have to be able to specifically identify that something was the cause for whatever the results were. If you can’t than it’s simply a correlation. Correlation is fine it’s the basis for most scientific peer reviewed research but you have to understand it’s evidence not proof of something.

Otherwise mistakes are made. Aka fat must make you fat because fat people have lots of fat or a vegetarian diet is healthy but perhaps the benefits are because a vegetarian is more likely to take better care of themselves in other areas of their life?

Peter, I enjoyed your and your commenters’ recommendations. Here are a couple of recent books that I enjoyed, not specifically on the scientific method, but relating to other subjects raised in your post:

“A Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race and Human History” by Nicolas Wade.

https://www.amazon.com/Troublesome-Inheritance-Genes-Human-History/dp/1594204462/ref=sr_1_1_bnp_1_har?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1400691472&sr=1-1&keywords=a+troublesome+inheritance

“Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain” by David Eagleman.

https://www.amazon.com/Incognito-The-Secret-Lives-Brain/dp/0307377334/ref=tmm_hrd_title_0?ie=UTF8&qid=1400691745&sr=1-1

Thanks for recs.

A few random thoughts in response to your post:

Portions of Michael Shermer’s “The Believing Brain” are interesting. He posits the evolutionary advantage of pattern recognition and causation assumption, even when erroneous, e.g., walking the Savanna and hearing a rustle in the grass: assume it’s a dangerous predator and survive vs. stop and analyze whether it’s a lion or merely the wind and be removed from the gene pool.

I don’t know that it will improve critical thinking or reasoning, but for sheer beauty, almost anything by Bertrand Russell is a joy to read.

Congratulations on the Ludwig/Friedman piece. I was reading it and thinking “these guys are channeling Peter Attia,” so I wasn’t surprised at the end to see Friedman’s NuScI association. And that made me think, yet again, how much I hope that NuScI is devoting resources to planning how best to communicate effectively the results of the research it is supporting. I have encountered a few obstacles in my recent efforts to educate friends about nutrition science. First, as you note, because people have little ability to discern whether lay press accounts of recent studies — or the studies themselves — have any validity, they assume that none of it can be trusted and the science will change, i.e., that today’s vilified carbs will be resurrected in a decade or so. So new results must be conveyed along with explanations about how and why prior understandings were incorrect. (You’ve done a fabulous job of this, but as you point out, explaining why things are wrong takes a lot more time than making incorrect assertions). And try as I might, I can’t get everyone to read your “How did we come to believe . . .” or to watch “Sixty Years of Ambiguity,” or to read Denise Minger’s book, or Gary’s, or Volek and Phinney’s explanation of the story. So that’s first: how to get normal people to pay attention to this news and not assume that it’s just another chapter in the ongoing and to-be-ignored saga. The second obstacle is the power of authorities. I have friends with cancer who will not read your “metabolic quirk” piece, or any of the other work on possible benefits of a ketogenic diet when battling cancer, because their oncologists said there isn’t anything they shouldn’t eat! I have another friend just diagnosed with autoimmune hepatitis who won’t explore all the work being done with food sensitivities and autoimmune disease processes because her doctor said there isn’t anything she shouldn’t eat (other than a few obvious things relevant to a compromised liver). This is all extremely frustrating and painful, and I’ve been doing a lot of fig tree resenting. So I think it will be essential for NuScI to focus on physicians and medical training, because we defer to doctors, and we will not see the massive change we need until the doctors are on board.

Finally, I met Kirk Parsley at Paleo f(x); his talk on sleep was fascinating. And thanks for turning me onto Tim Ferriss, who is also fascinating — and just taught me how to swim! How cool is that?

Thank you, thank you for all you do.

Great to hear. Kirk is my man. Glad you got to hear him speak.

Great blog. I can’t think of a more important topic. I have often thought about this issue and have come to the conclusion, similar to yours I think, that humans are just not very good at science. Your reasons why are very persuausive. I think we are creatures that understand nature by telling myths and stories and we are constantly trying (often without realizing it) to fit “facts” into a story that makes sense to us. Because we may be hard wired this way it will be very difficult to change. I also think that having one of our stories challenged can be threatening and makes us defensive. It also requires effort, the ability to sit with the discomfort that we may be wrong, and to accept the possibility that we may have to learn a new approach. Unfortunately, these are attributes that are often lacking. All of these problems are present in the current debate about nutrition which can be very frustating. (Today in the New York Times there was a short article on how Polar Bears appear to have a gene that allows them to eat “artery clogging fat” without getting heart disease). Please keep up your excellent work. You have many fans and supporters pulling for you.

I saw that article…so painful to read this drivel.

Brett, they must have been French Polar Bears!!

I love this fat phobia issue, in particular horrifying my family and freinds by eating a diet that 2/3 fat!

Christopher Hitchens was an incredible thinker, debater/orator and bastion of intellectual integrity. He wasn’t a “scientist” but remains an example of how to gracefully navigate the limits of ones own scientific literacy. His many YouTube debates and conversations with fellow scientists are always worth hearing.

This https://www.gnolls.org/3637/what-is-metabolic-flexibility-and-why-is-it-important-j-stantons-ahs-2013-presentation-including-slides/ piece on metabolic flexibility is a rare and welcome example of good concise scientific reasoning IMO.

Other scientists with very interesting and high-quality papers worth reading are Dr.Stephanie Seneff (MIT) https://people.csail.mit.edu/seneff/ & Dr.Dominic D’Agostino (USF Health, Florida) https://health.usf.edu/medicine/mpp/profile.html?person_id=24854 .

Gary Taubes is one of the best ‘scientific mentors’ that one could wish for. June 11th 2012 ago he granted me a Skype interview about nutrition – amazing – I couldn’t believe it and can’t thank him enough. Here’s the link: https://www.dropbox.com/s/3ltnly97gew40oq/gary%20taubes%20on%202012-06-11%20at%2018.26.mov

(Nota bene: my views on pre/probiotics & on the gut microbiome/microbiota have changed since then)

Interesting post Peter!

I’ll make sure to pass along your kind words to Gary.

This is an important topic that we tackled recently in a philosophy discussion group I belong to precisely to sharpen my critical thinking skills. I do not think of this in an all or nothing way. How could logic be invented without the ability to think logically already present? I agree there are strong incentives to make quick decisions about most things using limited information and observations of how those around us behave. And maybe that becomes a habit or the dominant thinking pattern because it sure is a lot of mental overhead to think critically about or apply the scientific method to every new thing we encounter. The pressures of daily life discourage us from taking the time to use our critical thinking muscles and over time they atrophy. When you combine that with all of the sources of information we are exposed to now, each of which should be examined critically before being accepted, one is often forced to rely on the opinions of others. So my approach is to always question and to make the effort to research and think critically about the issues that are most important to me while recognizing that those issues will not be a priority for everyone.

I look forward to checking out the great bibliography here.

Agree, it’s less that logic was “invented” per se. It’s more the codification that enabled “mass” adoption.

https://www.amazon.com/Brain-Bugs-Brains-Flaws-Shape-ebook/dp/B0054LXX5O/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1400696283&sr=1-1&keywords=brain+bugs

Hey Peter,

Thanks for mentioning the importance of being mentored in thinking logically. It’s a critically important skill and certainly not one that comes easily to a large portion of people.

I myself learned to think logically by playing chess, and my chess coach was instrumental in that regard.

I would highly recommend that you add the serious study of a game like chess to your list of things that are good for learning logical thinking.

Thanks for the piece, it is great as usual. Though there appear to be some typos…

Ken

Mentorship maybe the only vehicle for most of us. Please recommend a book about chess if you know one.

Logical Chess, Move by Move by Irving Chernev.

Yasser Seirawan is a good writer who wrote some great books for beginners, but they are mostly very specific (openings, endgames, analysis).

I learned a lot of what I know (about chess) from a book entitled “Chess tactics for students” by John Bain. It is, unfortunately, not a chess book for non-players of the game, and is a text for study of the game.

I think the best way to get people interested in chess is to show them the art of the game. For this, you would want a book of analysis of games of some of the best attacking players: Mikhail Tal, Bobby Fischer, and the legendary Paul Morphy. There’s one called “The King Hunt” by W H Cozens that details plenty of the most beautiful games of those three specifically.

Peter,

Please forgive the pedantry, in the interest of correcting a tiny error above.

Aldous Huxley was the author of fiction. His grandfather, Thomas Henry Huxley was Darwin’s bulldog.

Thanks for another great meaty read, and for more to read as follow up. Can’t wait to sink in my teeth!

A recent book on the topic, science and critical thinking: “Ignorance” by Stuart Firestein.

Patrick

Patrick, you’re absolutely correct and I “spoke” too soon…I need to slow down.

Hi Peter,

Good post. However, as a statistician, I that it is even worse. At times I think that we are very little better off than in antiquity when oracles were used. For example, you said that you are working on a post on insulin resistance. Yet when I did a search for ‘insulin resistance’ in Google scholar I got 1,690,000 hits. Just limiting the search to 2014 resulted 38,200 hits. These are huge numbers and are way beyond reading and analysis by any one individual. And that is before knowing that on a statistical basis a significant number are likely wrong or misleading.

Note that I am not disparaging your work. In fact I am looking forward to your article. I am just pointing out that you are working in a toxic minefield. The oracle had it easier, since if he was good, he would just provide the expected answer. Otherwise he might just loose his head.

You’ve reiterated my point! With 1.7 million “hit” what do you figure the signal-to-noise ratio is?

Thanks for a very interesting post.

I think anyone who regards man as a fundamentally rational animal is historically unconscious. The triumphs of reason are rare and minds like Feynman’s rarer still. Fighting your way through the tendencies you noted, and the social pressures, and the misinformation of the information age, to find some truth is a significant accomplishment. It requires the critical thinking skills you noted. All we need is 1/1000th of Feynman.

I think with diet we can put it to the test and experiment on our bodies to find what works for the individual. A little applied science can be very illuminating.

As to what might be done about the lack of thinking skills, I have seen some programs for high school students like Critical Thinking in Science (UNC) or Teaching Critical Thinking Skills (Dayton) that if I were king would be mandatory. However, it may be that only a few will ever really become better at thinking no matter what we do. We tend to run with the herd.

Thanks again. I enjoyed this piece.

Read, you may never be king of the world, but don’t give up on try to make this happen with high school kids.

This is a very interesting post. Framing logical thought and critical thinking skills in the context of millions of years of evolution is an insightful way of thinking about just how many biases need to be overcome in order to accomplish it.

If you need or want data regarding how difficult it is to learn (or teach others) to think critically, then there’s a pretty large literature. A pretty old (but still solid) review of the cognitive work is:

Halpern, D. F. (2001). Assessing the Effectiveness of Critical Thinking Instruction, The Journal of Education, 50(4), 270-286.

One of the huge challenges of this field is knowing how well such instruction and interventions generalize to novel contexts — It is hard to get people to think about anything critically. It is even harder to get people to develop a more general skill that can be applied across many domains. For example, it is not particularly fruitful to teach people how to critically approach a multiple choice, standardized test if that same critical approach can’t be applied to other situations in which they are consuming information (e.g. reading a popular press article about some scientific report). This idea of training and transfer has been around an extremely long time, but has recently witnessed a resurgence, largely because of a burgeoning sub-field in the cognitive neuroscience literature that you brought up. Results have been pretty mixed, so far, with more recent articles raising more questions about the effectiveness of recent techniques:

Redick, T. S., Shipstead, Z., Harrison, T. L., Hicks, K. L., Fried, D. E., Hambrick, D. Z., et al. (2013). No evidence of intelligence improvement after working memory training: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(2), 359.

Overall, this is to say that the problem of training critical thinking is probably even harder than we’re giving it credit for!

Best, and keep up the great work!

-Jeremy

Is there any hope?

Excellent point about training and greater ecology.

@Attia

“Is there any hope?”

Depends on what you think “hope” means, Peter. If Kahneman is correct – and he is piling up strong evidence, no doubt even despite the limitations of social/psychological science – then the answer is “no.” There’s no hope, because we all have monkey brains that have evolved only a limited rational capability and with a built-in irrational system that cannot be overcome, just compensated for. We’d need more evolution to “fix” the balance between Systems 1 & 2.

On the other hand, it can also be argued that we have a lot of hope, because some rationality is better than none, there is a range of rational capability that perhaps can be slightly improved through expert training, and we can work together to create better techniques, systems, and processes that will help us compensate for many of the predictable errors of System 1.

And on the third hand, we don’t need any hope, because as tribe- & family-based primates, we’ve evolved to be pro-social: to love our families, to be altruistic, to help not only our own children, but other people’s children as well, to show concern and care for others, to be happy & experience joy. These are irrational behaviors & capabilities but ones that make life beautiful and which we ought not be eager to trade away. 😀

Nice point of view.

Never thought about it this way. Very interesting. Following a leader is related to our human need to not be isolated; we need to belong to a group and have an identity. Historically those talented in persuasion and appealing – not necessarily wise or humane – have risen to lead tribes, states, religious groups. To think independently does seem to go against our very basic needs. So why are some of us skeptics and questioners (like me)?

I’ve been shocked to learn that often science is bad science, that doctors and researchers are like everyone else, reluctant to keep an open mind, unlikely to question what they learned in medical school and information received by their organizations. I assumed science reporters of all people would be the most eager to ferret out facts and lies.

I feel if you’re an honest person – with yourself – you eventually face the truth: that no one has the absolute truth and absolute answers about anything – certainly not health and nutrition. And I’m NOT a science person. But, I have a body, a brain and a history, and have always been pretty honest (got that from my mother).

Over the years I realized the experts failed me in my quest to lose weight, cure my eczema and carpel tunnel, not to mention my depression and overall emotional problems. I had to be scrupulously honest – which means I never know exactly what’s going on with me – and try to learn stuff on my own through reading, trial and error, thinking hard, and most of all sitting with that discomfort you talk about, the discomfort of disagreeing with everyone in the room and also of not having real answers, of sitting with a lot of contradictions. We don’t like that, we like the answers our leader provides. (As in our currently political climate of red and blue.)

So, here’s to the discomfort of being a critical thinker! Thanks for this great post.

Debbie, make sure you pick up Mistakes Were Made (but not by me). Definitely addresses your points.