Author’s note: This post was originally published in May, 2014. It has been updated to reflect my current thinking on the topic. Perhaps the best addition, by popular demand, is Rik’s coffee recipe (click the 1st inline footnote).

§

In 2012, I was having dinner with a good friend, Rik Ganju, who is one of the smartest people I know. And one of the most talented, too—a brilliant engineer, a savant-like jazz musician, a comedic writer, and he makes the best coffee I’ve ever had.1Here is the coffee recipe, courtesy Rik. I make this often and the typical response is, “Why are you not making this for a living?” Look for Vietnamese cinnamon, also known as Saigon cinnamon; you need two big dashes, if that. You need real vanilla (be careful to avoid the cheap versions with added sugar). Best is dissolved in ethanol; if that doesn’t work for you get the dried stick and scrape the pods. Then find a spice store and get chicory root (I’m a bit lazy and get mine on Amazon). You’ll want to replace coffee beans with ~10% chicory on a dry weight basis. If you’re on a budget, cut your coffee with Trader Joe’s organic Bolivian. But do use at least 50% of your favorite coffee by dry weight: 50-40-10 (50% your favorite, 40% TJ Bolivian, 10% other ingredients [chicory root, cinnamon, vanilla, amaretto for an evening coffee]) would be a good mix to start. Let it sit in a French press for 6 minutes then drink straight or with cream, but very little–max is 1 tablespoon of cream. The Rik original was done with “Ether” from Philz as the base. I was whining to him about my frustration with what I perceived to be a lack of scientific literacy among people from whom I “expected more.” Why was it, I asked, that a reporter at a top-flight newspaper couldn’t understand the limitations of a study he was reporting on? Are they trying to deliberately mislead people, or do they really think this study which showed an association between such-and-such, somehow implies X?

Rik just looked at me, kind of smiled, and asked the question in another way. “Peter, give me one good reason why scientific process, rigorous logic, and rational thought should be innate to our species?” I didn’t have an answer. So as I proceeded to eat my curry, Rik expanded on this idea. He offered two theses. One, the human brain is oriented to pleasure ahead of logic and reason; two, the human brain is oriented to imitation ahead of logic and reason. What follows is my attempt to reiterate the ideas we discussed that night, focusing on the second of Rik’s postulates—namely, that our brains are oriented to imitate rather than to reason from first principles or think scientifically.

One point before jumping in: This post is not meant to be disparaging to those who don’t think scientifically. Rather, it’s meant to offer a plausible explanation. If for no other reason, it’s a way for me to capture an important lesson I need to remember in my own journey of life. I’m positive some will find a way to be offended by this, which is rarely my intention in writing, but nevertheless I think there is something to learn in telling this story.

The evolution of thinking

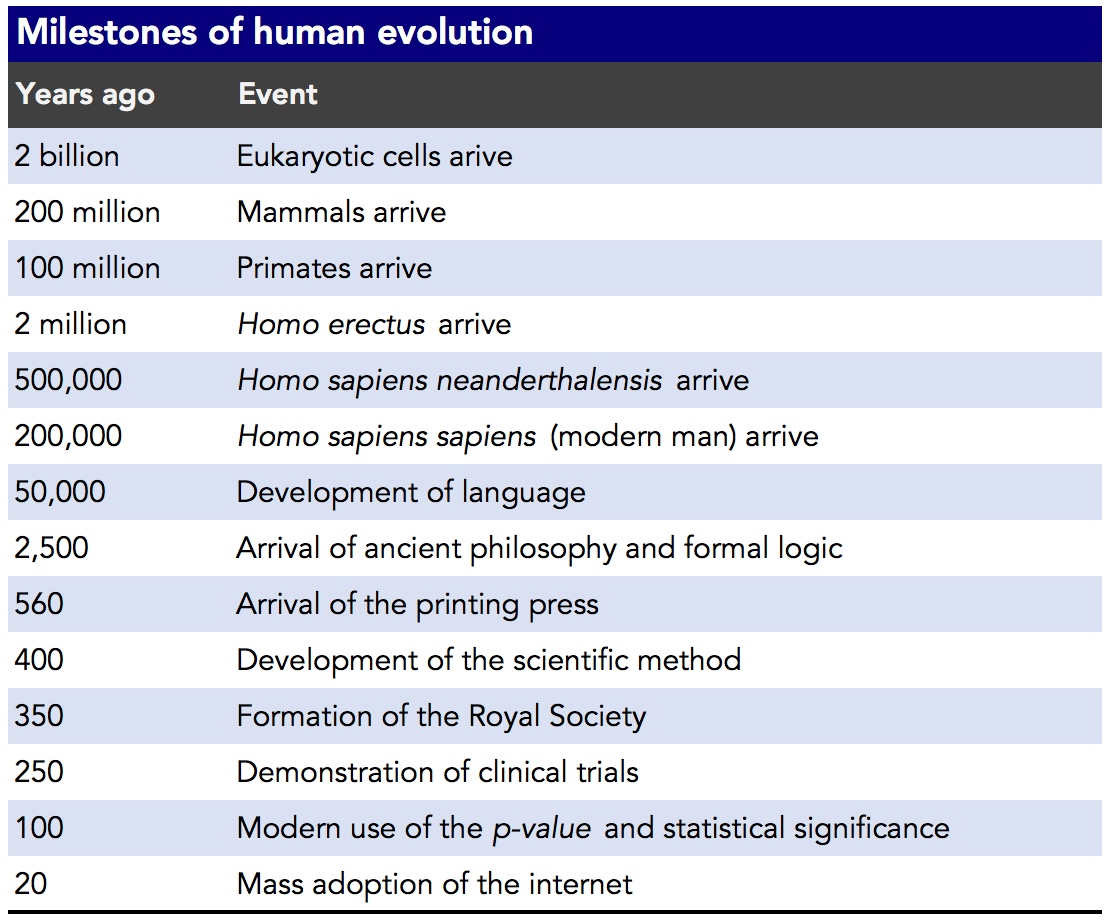

Two billion years ago, we were just cells acquiring a nucleus. A good first step, I suppose. Two million years ago, we left the trees for caves. Two hundred thousand years ago we became modern man. No one can say exactly when language arrived, because its arrival left no artifacts, but the best available science suggests it showed up about 50,000 years ago.

I wanted to plot the major milestones, below, on a graph. But even using a log scale, it’s almost unreadable. The information is easier to see in this table:

Formal logic arrived with Aristotle 2,500 years ago; the scientific method was pioneered by Francis Bacon 400 years ago. Shortly following the codification of the scientific method—which defined exactly what “good” science meant—the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge was formed. So, not only did we know what “good” science was, but we had an organization that expanded the application, including peer review, and existed to continually ask the question, “Is this good science?”

While the Old Testament makes references to the earliest clinical trial—observing what happened to those who did or did not partake of the “King’s meat”—the process was codified further by 1025 AD in The Canon of Medicine, and formalized in the 18th century by James Lind, the Scottish physician who discovered, using randomization between groups, the curative properties of oranges and lemons—vitamin C, actually—in treating sailors with scurvy. Hence the expression, “Limey.”

The concept of statistical significance is barely 100 years old, thanks to Ronald Fisher, the British statistician who popularized the use of the p-value and proposed the limits of chance versus significance.

The art of imitation

Consider that for 2 million years we have been evolving—making decisions, surviving, and interacting—but for only the last 2,500 years (0.125% of that time) have we had “access” to formal logic, and for only 400 years (0.02% of that time) have we had “access” to scientific reason and understanding of scientific methodologies.

Whatever a person was doing before modern science—however clever it may have been—it wasn’t actually science. And along the same vein, how many people were practicing logical thinking before logic itself was invented? Perhaps some were doing so prior to Aristotle, but certainly it was rare compared to the time following its codification.

Options for problem-solving are limited to the tools available. The arrival of logic was a major tool. So, too, was the arrival of the scientific method, clinical trials, and statistical analyses. Yet for the first 99.98% of our existence on this planet as humans—literally—we had to rely on other options—other tools, if you will — for solving problems and making decisions.

So what were they?

We can make educated guesses. If it’s 3,000 BC and your tribemate Ugg never gets sick, all you can do to try to not get sick is hang out where he hangs out, wear similar colors, drink from the same well—replicate his every move. You are not going to figure out anything from first principles because that isn’t an option, any more than traveling by jet across the Pacific Ocean was an option. Nothing is an option until it has been invented.

So we’ve had millions of years to evolve and refine the practice of:

Step 1: Identify a positive trait (e.g., access to food, access to mates),

Step 2: Mimic the behaviors of those possessing the trait(s),

Step 3: Repeat.

Yet, we’ve only had a minute fraction of that time to learn how to apply formal logic and scientific reason to our decision making and problem solving. In other words, evolution has hardwired us to be followers, copycats if you will, so we must go very far out of our way to unlearn those inborn (and highly refined) instincts to think logically and scientifically.

Recently, neuroscientists (thanks to the advent of functional MRI, or fMRI) have been asking questions about the impact of independent thinking (something I think we would all agree is “healthy”) on brain activity. I think this body of research is still in its infancy, but the results are suggestive, if not somewhat provocative.

To quote the authors of this work, “if social conformity resulted from conscious decision-making, this would be associated with functional changes in prefrontal cortex, whereas if social conformity was more perceptually based, then activity changes would be seen in occipital and parietal regions.” Their study suggested that non-conformity produced an associated “pain of independence.” In the study-subjects the amygdala became most active in times of non-conformity, suggesting that non-conformity—doing exactly what we didn’t evolve to do—produced emotional distress.

From an evolutionary perspective, of course, this makes sense. I don’t know enough neuroscience to agree with their suggestion that this phenomenon should be titled the “pain of independence,” but the “emotional discomfort” from being different—i.e., not following or conforming—seems to be evolutionarily embedded in our brains.

Good solid thinking is really hard to do as you no doubt realize. How much easier is it to economize on all this and just “copy & paste” what seemingly successful people are doing? Furthermore, we may be wired to experience emotional distress when we don’t copy our neighbor! And while there may have been only 2 or 3 Ugg’s in our tribe 5,000 years ago, as our societies evolved, so too did the number of potential Ugg’s (those worth mimicking). This would be great (more potential good examples to mirror), if we were naturally good at thinking logically and scientifically, but we’ve already established that’s not the case. Amplifying this problem even further, the explosion of mass media has made it virtually, if not entirely, impossible to identify those truly worth mimicking versus those who are charlatans, or simply lucky. Maybe it’s not so surprising the one group of people we’d all hope could think critically—politicians—seems to be as useless at it as the rest of us.

So we have two problems:

- We are not genetically equipped to think logically or scientifically; such thinking is a very recent tool of our species that must be learned and, with great effort, “overwritten.” Furthermore, it’s likely that we are programmed to identify and replicate the behavior of others, rather than think independently, and independent thought may actually cause emotional distress.

- The signal (truly valuable behaviors worth mimicking)-to-noise (all unworthy behaviors) ratio is so low—virtually zero—today that the folks who have not been able to “overwrite” their genetic tendency for problem-solving are doomed to confusion and likely poor decision making.

As I alluded to at the outset of this post, I find myself getting frustrated, often, at the lack of scientific literacy and independent, critical thought in the media and in the public arena more broadly. But, is this any different than being upset that Monarch butterflies are black and orange rather than yellow and red? Marcus Aurelius reminds us that you must not be surprised by buffoonery from buffoons, “You might as well resent a fig tree for secreting juice.”

While I’m not at all suggesting people unable to think scientifically or logically are buffoons, I am suggesting that expecting this kind of thinking as the default behavior from people is tantamount to expecting rhinoceroses not to charge or dogs not to bark—sure it can be taught with great patience and pain, but it won’t be easy in short time.

Furthermore, I am not suggesting that anyone who disagrees with my views or my interpretations of data frustrates me. I have countless interactions with folks whom I respect greatly but who interpret data differently from me. This is not the point I am making, and these are not the experiences that frustrate me. Healthy debate is a wonderful contributor to scientific advancement. Blogging probably isn’t. My point is that critical thought, logical analysis, and an understanding of the scientific method are completely foreign to us, and if we want to possess these skills, it requires deliberate action and time.

What can we do about it?

I’ve suggested that we aren’t wired to be good critical thinkers, and that this poses problems when it comes to our modern lives. The just-follow-your-peers-or-the-media-or-whatever-seems-to-work approach simply isn’t good enough anymore.

But is there a way to overcome this?

I don’t have a “global” (i.e., how to fix the world) solution for this problem, but the “local” (i.e., individual) solution is quite simple provided one feature is in place: a desire to learn. I consider myself scientifically literate. Sure, I may never become one-tenth a Richard Feynman, but I “get it” when it comes to understanding the scientific method, logic, and reason. Why? I certainly wasn’t born this way. Nor did medical school do a particularly great job of teaching it. I was, however, very lucky to be mentored by a brilliant scientist, Steve Rosenberg, both in medical school and during my post-doctoral fellowship. Whatever I have learned about thinking scientifically I learned from him initially, and eventually from many other influential thinkers. And I’m still learning, obviously. In other words, I was mentored in this way of thinking just as every other person I know who thinks this way was also mentored. One of my favorite questions when I’m talking with (good) scientists is to ask them who mentored them in their evolution of critical thinking.

Relevant aside: Take a few minutes to watch Feynman at his finest in this video—the entire video is remarkable, especially the point about “proof,”—but the first minute is priceless and a spot on explanation of how experimental science should work.

You may ask, is learning to think critically any different than learning to play an instrument? Learning a new language? Learning to be mindful? Learning a physical skill like tennis? I don’t think so. Sure, some folks may be predisposed to be better than others, even with equal training, but virtually anyone can get “good enough” at a skill if they want to put the effort in. The reason I can’t play golf is because I don’t want to, not because I lack some ability to learn it.

If you’re reading this, and you’re saying to yourself that you want to increase your mastery of critical thinking, I promise you this much—you can do it if you’re willing to do the following:

- Start reading (see starter list, below).

- Whenever confronted with a piece of media claiming to report on a scientific finding, read both the actual study and the media, in that order. See if you can spot the mistakes in reporting.

- Find other like-minded folks to discuss scientific studies. I’m sure you’re rolling your eyes at the idea of a “journal club,” but it doesn’t need to be that formal at all (though years of formal weekly journal clubs did teach me a lot). You just need a good group of peers who share your appetite for sharpening their critical thinking skills. In fact, we have a regularly occurring journal club on this site (starting in January, 2018).

I look forward to seeing the comments on this post, as I suspect many of you will have excellent suggestions for reading materials for those of us who want to get better in our critical thinking and reasoning. I’ll start the list with a few of my favorites, in no particular order:

- Anything by Richard Feynman (In college and med school, I would not date a girl unless she agreed to read “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman”)

- The Transformed Cell, by Steve Rosenberg

- Anything by Karl Popper

- Anything by Frederic Bastiat

- Bad Science, by Gary Taubes

- The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, by Thomas Kuhn

- Risk, Chance, and Causation, by Michael Bracken

- Mistakes Were Made (but not by me), by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson

- Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman

- “The Method of Multiple Working Hypotheses,” by T.C. Chamberlin

I’m looking forward to other recommendations.

Two thoughts on imitation:

1. Like animals, children and babies seem hard-wired to do it. Kids make great mimics. Which is why, I think, we have younger and younger kids putting on amazing performances of one sort or another, thanks to YouTube videos facilitation of finer and finer mimicry. (Though I do wonder how a nine-year old singer’s gestures and apparent emotion can be authentically rooted in experience.)

2. One of my favorite books is Julian Jaynes’, “The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind.” Jaynes believed that before around 1,500 B.C. pretty much everyone hallucinated voices (of parents or other authority figures), that there was no ego as we know it, i.e. no subjectivity, no mediating “I” or “me,” no interiority or self-talk. This is a state nearly impossible for us to imagine. But Jaynes shows how conceptualization, thinking, learning, etc. still happened unconsciously, thus enabling civilization to grow. (With no interior “I” to complain, I wonder, how else might things like the pyramids have been constructed?) Jaynes’ theory is, of course, controversial. But it is stimulating and, as a writer and thinker, he makes great company.

The scientific method requires interiority, thus a capacity to weigh and judge. Before the development of consciousness (roughly paralleling the development of writing, according to Jaynes), men were, he claimed, automatons, responding to hallucinated voices much in the manner of modern day schizophrenics. (These last, unfortunately, suffer the pain of ‘knowing what they’re doing; they are conscious.)

Without the prior development of consciousness/subjectivity, then, the scientific method would have been impossible. So it makes sense that since consciousness (“there being someone home”) introduces what I would call a kind of ‘friction’ in mentation, then the default response would be the easier one, i.e. imitation. For some, doubt can be frightening.

Interesting point. I see it every day with with my daughter, too. Imitation has been such a remarkable “tool” for us for so long. But if a boxer can learn to NOT flinch (there is a FANTASTIC short e-book on this), then I’m confident we, too, can learn to not imitate blindly.

This ebook? https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B0062Q7S3S/

Free, but also a pdf here: https://raouldify.files.wordpress.com/2011/12/2011_1203-the-flinch.pdf

Exactly! Great read.

This topic came up at dinner last night, I had a brief moment where something bugged me and I just had disdain for the modern world we live in, the girlfriend asked “do you think we’re evolving too quickly?”, I said “no, I just think technology and society is a few dozen thousand years ahead of where it should be.”

As to mimicry, in the end we’re just overwhelmed with options for a “healthy” lifestyle, and in the last 5 or so years especially so as everyone is now not just exposed to, but often barraged with constantly as many “sciencey” reasons for following a given health and nutrition path. Being constantly connected has it’s downsides. At some stage we just have to commit to something, pick a thought leader who expounds a system that seems tenable and fits in with our desired lifestyle, then tweak as necessary – but not every damn day.

It’s a telling sign that your most popular posts are about what YOU actually eat and do.

And also just yesterday I stumbled on an obscure magazine article from 1950 (which I believe was mentioned in GCBC or WWGF) all about how to have an “eat all you want reducing diet” – driven by Dr A W Pennington, which is effectively what we now know as somewhere between keto and PHD. Reproduced here:

–> https://highsteaks.com/an-eat-all-you-want-reducing-diet-elizabeth-moody-1950/

(There’s a ton of great quotes in there)

The point being I’ve read and have notes written down on science studies numbering in the thousands, yet as I read the article and got taken back into some quaint notions and ideologies, I found myself just thinking that this article was so simple yet prescriptional with *just enough* science that it’s a diet and lifestyle I could really follow (plus it’s also not much different from my own), and I don’t need to read another 20 RCTs a day seeking to confirm my bias, or be bombarded by “The Others” who want me to read their own confirmation biases.

Nice find, Ash.

Hello Friends. Thanks to Peter on another stimulating post and to all of you for adding color and nuance here in the comments. If you have gained from this (or the coffee recipe), I wonder if you would support the following: I released a song last week called “Stars Fell on Daniel” for a friend who passed away recently. I’d like to donate the profits from download sales to research in mental health illness, and to suicide prevention hotlines – at least my local hotline. I released the music under the name Ganfunkel, the album is called Fighting Music with Music, and the song is Stars Fell on Daniel. Personnel joining me on this piece have recently recorded and/or toured with the Kronos String Quartet, Terry Riley and John McLaughlin. If those names mean anything to you, and you have 99 cents to spare, please consider a purchase at itunes, amzn, or anywhere downloads are sold. The song is instrumental blending tabla, guitar, and woodwinds and unfolds into a lyrical somewhat meditative lament for this lost friend.

Please accept my thanks in advance for those willing to offer support. – Rik

Peter, thanks again for a brilliant post.

I sometimes wonder if I am the only one who thinks the way I do (which some might describe as obsessive when it comes to learning and understanding) but thank God for the web. You are part of the peer group I refer to, thank you for keeping me sane (or insane depending on your viewpoint).

I can 100% relate to your points on 75%/25%. In a nutshell, my family are fat (thank God they don’t read this but if they did perhaps they wouldn’t be or at least as much) but I am not. I used to be (lost about 70 pounds and maintained for 10 years, now BMI around 18, looking to eliminate last bits of ‘skinny fat’) but similar to yourself it was a tough learning curve to really understand how my body works. It is amazing that I almost now feel like I am one of these naturally lean people as remaining in this state for so long I find it hard (in a good way) to shift my weight either upwards or downwards – this last element of control was learned from the knowledge I acquired after following your site and reading wider.

Anyway to the point, resources. There is nothing which sums up and explains this phenomenon better in my opinion in an accessible to the lay population than Daniel Kahneman’s ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’. This is a must read. He shows how we often default to a kind of natural pattern recognition survival mode which defies logic. It takes so much more effort to pause, take a breath and really apply our critical minds. Kahneman developed a whole new language for describing our natural tendency towards this and teaches us how to recognise some of the situations where our ‘system 1’ (the non-logical) thought process can prevent us from making rational decisions. A good example of this was where students were offered either a mug or a sum of money say $6, most chose the $6. However, where students were given the mug first as a gift then offered $6 to part with it most refused to sell.

We like stories and we are hard-wired to recognise patterns therefore we tend to attribute meaning even where the evidence (or scientific experiment) proves these theories to be wrong. For example, the simplistic view of calories in, calories out (where calories are ‘perceived calories’, calories in are via bomb calorimetry and calories out are via some arbitrary value the popular media agree upon e.g. it takes x calories to climb the stairs). This is a powerfully simple story that many are unwilling to question.

I disagree on one small point you make about blogging probably not contributing to scientific advancement. I think that in general this is true, but in the case of your blog, you bridge the gap between the scientific and lay population creating an irresistible force (for some) pulling them closer towards the science. You are contributing big time!

One other resource which might be of interest is Nate Silverman’s ‘The Signal and the Noise’ which shows how we often apply meaning to data even where there is more noise than signal.

Finally, thanks for the props to Fehnman and the reference to Napoleon Dynamite 🙂

JJ, thanks for sharing all of this. I can’t believe I forgot to add Danny’s book (which I’ve read). Need to fix that! I’m going to send this post to Danny, also, given how many folks, like you, have brought it back to his work. This is what happens when I rush blog posts…sloppy work!

I hope you’re right about blogging…I guess time will tell. Lastly, glad at least one person could “hear” Napoleon Dynamite saying, “Lucky…!”

Another great post and many very sharp commenters! I’ve been wondering about this subject for some time. Example: I prescribe dietary changes to assist my patients with blood glucose control and they ignore my advice, telling me, “fat is bad for you!” I provide them with reliable sources some of which are noted above, and they continue to eat in the way that has damaged their metabolism and body habitus.

I was assuming it was “sugar brain” a phrase i’ve used to explain to my staff that they are having cognitive difficulties as a result of high BG. But, even with better control they don’t believe me and rely on some TV doc and his/her infomercial-like presentation. Sigh.

A great quote : ” Don’t believe anything you hear and only half of what you see.” I don’t know who to attribute this one to….it fits a lot of thinking patterns.

Thanks for the great reading list.

Lauren, I hear your frustration. Maybe such patients will be swayed by Dr. Oz changing his tune?

Great post, Peter! I would just add that not only does one need to read the media carefully, but one also needs to read those original papers carefully and not take the authors at their word about what their research implies. I would suggest that a surprisingly large proportion of health researchers don’t interpret their studies correctly, and the media often just repeats what they say in their papers or what the university press release says. When reading the scientific literature, my strong suggestion is to avoid reading the Discussion or the authors’ conclusions in the Abstract. Read the Methods and the Results first, and make your own interpretation.

Absolutely. The last time I looked into it (about 10 years ago), one of most surprising facts I found was that some 70-75% of peer-reviewed published research was never cited again–in other words about 3/4 of all published research is pure junk. Others have estimated that as much as 90+% is likely outright wrong.

Ioannidis, J.P.A., 2005.

Why Most Published Research Findings Are False.

PLoS Medicine, 2(8).

Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1182327/

————————————————

I will likely be citing this and others like it in my own publications.

Epic paper.

Peter,

Great post as usual. I just finished “Surely you’re joking Mr. Feynman” after you suggested it. A great book. A example of imitation in his book is his teaching in Brazil. He remarks how the students there had no conceptual ideas of physics but instead was just learning the equations (without knowing what they mean) and did not ask questions because they thought they needed to imitate other countries by having a big science dept. I can personally say that the more advanced the math got for me in school (I quit at calculus) the less they bothered telling me what the equations meant to the point where I no longer could understand or remember the equations because they had no meaning behind them.

As already recommended “Thinking, Fast and Slow” by Daniel Kahneman is a great book on the subject. One test he talks about is how people resort to “non-thinking” as their glucose levels got lower. Made me wonder if us in ketosis use “thinking” more than non-keto because of a steady supply of brain energy? Something to look into from a nutritional side for sure.

Love Frederic Bastiat. Another economist I would recommend is Friedrich Hayek. His book “The Fatal Conceit” gets very much into how people imitate more than thinking logically and how that applies to economics and the type of words we even use. Thanks again.

Great rec. Thank you.

My high school education occurred in the 1960s. The science teaching staff was very skilled and even midgrade students were offered challenging fare. I am not mathematically inclined at all (I tend to be “arty”) but my science education was amazing and the effects of it have carried throughout my life. Now high school science has been dumbed down and the equivalent to the classes I took can be found at universities or sometimes at community colleges. But you have to complete many mathematics classes before you can take them. My son, who is mathematically impaired as I am, was eager to take science classes, but it was not allowed even though he wa a 4.0 student. My point is, decent science classes are only offered to a narrow population, and we’re suffering as a society because of it. I think everyone needs to be educated in chemistry, biology, and physiology.

Did your wife read” Surely your Joking”? And had she not, have you thought about what that loss might have meant to you?

You mention at times in the post ” the signal from the noise”, but wondered why Nate Silver book not on the list.

I think if most just read this book, they would be on the path to improved critical thinking and might not have to delve in to more complex thinkers such as Popper.

Taleb’s Fooled by Randomness said it all for me, and his other two I found to be derivatives, variations of the thinking discussed in the first book.

Lack of critical thinking is a major shortcoming of the educational system. To go through HS and college and not have a modicum of critical thinking skills is a tragedy!. Of course schooling in our politically correct culture, has become watered down. All should be required to study statistics/probability which would go a long way in achieving a level of critical thinking skills..

Great post!

1. Of course she did! We would not have got to date #5 if she had not. And she “had” to read The Transformed Cell (also on my list). In retrospect, I’m lucky she didn’t tell me to screw myself, as I would have lost out on the opportunity to marry her (by my calculation, there are only 7 women on this earth could happily live with me).

2. I haven’t read Silver’s book, but I’ve just ordered it.

3. I loved FBR (better than BS, actually). Probably should be on the list, also.

7 women! I won’t ask what the margin of error in that calculation might be!

Anyway, your wife is apparently a flexible and accepting soul. Many would have flipped you the bird!

Silver book is relatively elementary; good discussion of Bayes theorem

thanks for the post

I think it’s +/- 1. But she is a very unique person.

(Brief note to say thanks x 1M for reply, am amazed & impressed you are on first name terms with one of my heroes, more evidence for the theory that you possibly are a legend!)

Ha ha. I’m no legend, but I’m lucky to be friends with a few.

I also highly recommend Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow. Daniel Kahneman won a nobel prize for his research into cognitive biases which is exactly the subject of this blog. He includes lots of different categories of cognitive biases and he also has solutions for over coming the biases.

Yup, on the list.

I think the following 2 books by Ben Goldacre are worth looking at:

Bad Science (2008)

Bad Pharma (2012)

He also has a couple of TED videos which I like as well:

https://www.ted.com/talks/ben_goldacre_battling_bad_science#t-614314

https://www.ted.com/talks/ben_goldacre_what_doctors_don_t_know_about_the_drugs_they_prescribe

Blimey, an intelligent and erudite blog. My friend Alan might even like it https://goodlondoncopywriter.co.uk/ I mention him because he’s been a friend for nearly two decades and rarely agrees with anything I say, he certainly doesn’t take anything on face value. A true friend indeed.

I have two comments to make, both of which are going to be quite long and so, I’ll split them up into separate comments. The first comment is about the pain of not imitating everyone else. As far as I’m concerned, that pain is real but, if you do it often enough, like anything else, your brain normalises it.

In the early nineties, I was given the task of designing a system so complex that everyone except my mentor and my employer said that it was impossible. My employer was one of the largest law firms on the planet and they hoped that since I was “untrammelled by a formal education”, that I could do it – they realised that I didn’t have to “think outside of the box” because I just don’t have a “box”. My mentor, one of the most senior consultants for one of the “big three” management consultancies, somehow knew that I could do it and spent seven years supporting me in my research before I designed the thing.

I won’t bore you with what the system was but instead, I can contribute the lessons that I learned in my journey of designing it.

First, I think it was the physicist Murray Gell-Mann, who really jumped up and down with rage when something wasn’t simple and elegant, on the basis that it must be wrong. As far as I’m concerned, he was right: if something is complicated, you’re thinking about it in the wrong way. By “wrong”, I mean in a way that doesn’t actually help you in thinking through the problem – and if you go too far down that road, the problem will bury your brain. I believe that’s called “Analysis Paralysis”.

Second, memory is key – you need to have a wide fact base to draw on, so that you can apply your concepts to it and test things out in the simulator that is your brain. On my journey, I researched the telegraph system, the railways and healthcare (since I was designing a national infrastructure that was much more complex than any of those). I learned about how these things evolved, how they were financed and the politics of the time that affected them.

So, thirdly, we come to the fact that the brain is a simulator and if you put enough information into it, it will simulate veridically i.e. the simulation it runs will match reality. This is a key point because, once you have confidence in your ability to simulate, then you can accurately simulate something that’s never been done before. This situation gave me the most pain, as you can imagine, but I also got into a “god-like” (with a small “g”) scenario, where I could just create at will.

Fourth is the understanding the dynamics of your own learning curve. Know that you’re as dumb as anything when you start something but also know how you learn effectively – and then apply those techniques to everything you learn that’s beyond trivial.

Fifth, understand the structure of the creation that you’re creating inside of – it’s self similar i.e. you will see the same patterns repeating themselves at any level you look at. A good one is a tree. You will see a dendritic pattern (tree-like) on a microscopic level in the soil, on a human scale in lungs, on planetary scale in river deltas. Learn these patterns and life will be simpler – your thinking will be simpler but much more powerful

Sixth, understand what far from equilibrium dissipative systems are – those are the ones that are born, grow and then die (like a business, or on a smaller scale, a business transaction), not the ones that are manufactured on a production line. The reason for knowing this is so that you know what needs to be controlled and you don’t bother with trying to manage chaos that can never be controlled – you just corralle that stuff e.g. stick it in a database in such a way that you can get at it later.

Seventh, Kahneman, along with Tversky won the nobel prize for doing the research that changed Howard Raiffa’s received wisdom on negotiation – rational people do not respond rationally throughout the risk curve – rational people are more willing to spend their way out of a risk, than they are to buy a benefit. This gets you into the (in my opinion) rather dodgy ground of neuro-linguistic programming, so that you frame your wares in terms of helping a buyer to ameliorate a risk, rather than to gain a benefit.

The reason I think that neuro-linguistic programming is dodgy ground is because I see that using it on someone who’s unaware of it is the same as spiking someone’s drink at a party. It’s just unfair and that’s not done in a humane society.

Okay, now for my second comment and this one is on diet. Another decade – long friend of mind is a leading psychotherapist in the UK https://www.klearminds.com/ and, many years ago, we had a conversation about diet and blood groups.

I spent five years in a vegetarian boarding school, which only served organic food. I got sick, I got cold, I was miserable. “How can this be?” You ask. Well, I found it really interesting that once a day kid found out that I could shoot and he invited me to his dad’s farm for “bunny blasting” and to help myself to pheasants, I got a lot better, faster and stronger. I’m an O positive blood group and over the years, I’ve developed a high protein, low carbohydrate, full fat, organic diet, without the weird fats that are new to us, like rapeseed oil and sunflower oil and I never get ill.

My psychotherapist friend did get very ill and, eventually, it was pinned down to her diet. Not having been taught to cook, she was very distressed when she eventually received her diet sheet and had no clue of what to make of it. I spent several weeks with her, making meals out of the ingredients from the diet sheet and then she suddenly said to me “but this is your diet, it’s what you eat”. “We’re the same blood group”, I replied and my friend is now fully functioning and cooks lovely meals.

My partner and my son are both B+ and if they imitate me and eat my diet, they get ill. They lack energy, they get constipation, wild flatulence and they’re just generally miserable. Their diet is beans, not beef, duck, not chicken, loads of fruit (which I like but I’m really not bothered about) and about the same level of carbohydrate as me. That said, they can handle beef if it’s minced and served with a load of beans. So chile con carne is a meal that suits us all, whereas steak and chips is not.

I know that two cases are not statistically significant but I don’t meet B+ people very often, because they’re rare in the population. However, we recently had our second child delivered, and whilst my partner was in the throes of labour, the hospital staff realised that they didn’t have her blood group noted down. I told the mid-wife that my partner was B+ and that the hospital would probably have to go hunting in the basement for some replacement blood, since it’s so rare. “Oh, the same as me”, the midwife said. So, then I put it to her that her diet is beans, not beef, duck, not chicken, loads of fruit and not much carbohydrate. I did this point by point and she agreed with each point.

Okay, now you get the point, I’m going to get really left field on you. I have no idea about men but I’ve encountered a lot of “fat” women, who are not actually fat – if you prod their “fat”, it wobbles like water. It is water and I can tell you why but I have to mention the word “orgasm” and if you’re not comfortable with that, then stop reading now.

As a very lean and muscular guy, spending five years in a mixed boarding school, watching the females around me agonise about their figures as they developed through puberty, I discovered two things. First, all women have an intrinsic beauty that’s unique to each of them, second, they’re being conned into thinking they’re fat by an industry that knows women will hop from diet to diet, when “diet” is not the solution.

The “solution”, should that be desired (and I’m a great fan of allowing a woman to be who she is, naturally, because as a man, I then get the benefit of a happy, contented woman who is authentic to herself) is to come in pints when she orgasms.

This is really simple to achieve and you’ll see the difference in 10 days, if not sooner. So here’s how it goes. There’s a point inside a woman’s vagina called the Anterior Fornix (that’s “front arch”, to you and me) it’s the point where the top of her cervix joins her vagina. If you stimulate that, as you would a G-spot, she’ll feel the need to pee. This is what’s called a “shadow sensation” by the physiology crowd because you’re just stimulating the nerve that sends a signal to the brain that tells a woman she needs to pee. So she should pee beforehand, just so that she’s sure everything is fine.

If she pushes, during this type of orgasm, as she would push to push a pee or a poo out, then, after a bit of practice, her orgasm will be accompanied by pints of liquid coming out and with some force (so be kind to your mattress and protect it). I’ve done this so many times with so many women, with so many body types, I’ve satisfied myself that this is a truth. Women who use this type of orgasm as part of their sexual repertoire are, in my experience, more settled in themselves, more loved and more self-determined (handy, if you’re a bloke) and, in their forties, they look and feel in themselves to be “ten years younger”.

The key to achieving this, for a man, is to get off “transmit” and get on to “receive” what a woman’s body is telling you to do, then you’ll find out why you have such physical strength and stamina. You’ll need it, as she “rides the tiger’s tail” as the far eastern sexual martial artists say.

I’d be really interested if anyone has an equivalent solution for men, not because I need one but because I find biochemistry and physiology really rather fascinating.

So sometimes fat isn’t fat but just ‘water’ that needs to be flushed out by orgasm. Is that truly what you were saying? So somehow the water comes from the fat cells in the body and shoots out through the uretha instantly? How does it get there? What about children? What about old people?

Also there is as far as I can tell no proof to the blood type diet. While I don’t deny the possibility but I think you are jumping to conclusions. That type of mentality is exactly what caused the diet issues plaguing most of the western world.

Very interesting. I should read up on this

Hi Peter-

I’ve been a long time reader- I’ve been on a ketogenic diet (check glucose and ketones periodically) for 6 months. I’m not diabetic, not overweight (5’9″, 148 lbs), not a smoker, exercise pretty regularly (walking, hiking), no immediate family history of issues, and feel better than ever! I was leaning metabolic syndrome, I’ve lost 17 lbs from abdomen in 6 months, but now weight stable. My lipid profile 5 years ago (last time I had it checked) was identical to yours pre-diet change. After my last 6 months, I just did an NMR LipoProfile to make sure the train didn’t come off the tracks and the results are astronomically, horrifically bad. I have read of this phenomenon rarely, and you have spoken of it on some video’s. Can you advise on a low carb doctor that can interpret and advise me, look into Thyroid, or tell me to leave it alone, etc? I’m in unchartered waters given the current medical community! If you need a case study for NuSi, give me a shout out!! hehe – thx for any help? No need to post in the comments-

LDL-P: >3500 (OMG walking dead)

LDL-C: 323 (*&$% walking dead)

HDL-C: 43 (ok)

HDL-P: 24.0 (low)

Tri: 148 (on damn near 0 carb)

Small LDL-P: 1848 (Jesus $%#$)

LDL Size class: 21.1 (Pattern A)

LP-IR Score: 43

Lost in Northern CA……….

I have an idea what’s wrong, but I would need to see a few other labs and it would take 3 months at least to tweak. I wish I knew a good doc to help with this. Tom Dayspring, who is in VA, is the other other person I know taking the same approach to mine in situations like this. I’ll try to address in part X of the cholesterol piece.

Thx for the response Peter-

Hard for me to even conceptualize what is happening- anything you can do to shed light would be amazing- In the interim I plan to check my CRP, Thyroid panel, and Lp-PLA2 to try and see if anything looks amiss, while adding back some low GI carbs- I’ve watched many of Mr. Dayspring’s video’s, have not seen him address this.

You’ll need to register, but this is a good start: https://www.lecturepad.org/index.php/2014-04-09-18-46-55/lipidaholicsanaonymous/1140-lipidaholics-anonymous-case-291-can-losing-weight-worsen-lipids

Some People

I have wondered about this sort of thing –

My thoughts being that for some reason food combustion (oxidation) – the last step in the ATP cycle( I think) –

is not complete – resulting in un-oxidized food remaining in the bloodstream – the low-carb diet making this substance risistant to being stored as fat –

in other words – the only path the un-oxidized food can take is too float around in the bloodstream carried by excess amount of LDL-P (particles)

Sorry if this is a distraction from the main piece but is related to the concept of non-mainstream thinking.

Have you had any experience of a system called Arx Fit (don’t worry I don’t work for them, I’m in the UK where you can’t even access the machines)?

Its basically a weight exercise machine that adapts to individuals so that a super weak (aka moi) or incredible hulk could use it and both feel like a house is coming down on them as it matches your ‘force output’ at each part of the ‘strength curve’ i.e. it makes any movement or lift damn hard at each part of the lift.

The part I like is that it works equally well for any level of fitness (or weakness) and because it is so efficient, apparently you can complete a meaningful workout in say 30 mins. I heard Dr Rocky Patel comment that this could be good for diabetics as would put more force on eccentric movements (e.g. when you lower the weight) allowing muscles to ‘soak up’ more blood sugar.

See, even body builders use science … kinda ….. 🙂

I would not be too concerned right now, we do not know to well what all these things really mean. My cholesterol skyrocketed on full-keto initially. The last time I researched I found that the most trustable ratio for general health is Triglyceride to HDL. Yours is actually 3.5, just between cutoff for between A and B pattern. We dont even know if that stuff is meaningful, but according to what I remember th TG to HDL is better than any other mainstream ratio, like total colesterol, ldl etc.

I have one APO e4 Gene for example, according to some studies this mandates a low-carb (Dr Dayspring might disagree re high-fat on APO e4, but I am not sure he has justified this anyhow) , high activity lifestyle (=5 times a week moderate exercise), with that I appear to have excellent health, endurance and even blood labs, even the ones we dont know a lot about.

You could try exercising 5 times a week and just not force any more weight loss, which is probably not on your list. You are already ketogenic, you could soften that introducing much more leafy green stuff and in turn add in a fast day here and there. Actually I did a multiple day fast and got my blood labs to see how my fat metabolism works while using only stored fats. We are all very different with our genes and things we did to our body, you will have to experiment.

oxLDL and CRP is a good idea, maybe much more important than the other stuff.

Hi Peter-

Updating my original post, the case study you referenced was an amazing read. For lack of direction, I followed the general intent outlined in the write-up: reduced SAT (eliminated coconut oil) , increased MUFA, increased carbs to just out of ketosis, and lots of leafy greens- Voila, an amazing reversal in lipid profile! Gene expression is normally some vague, amorphous thing, but seeing raw data tied directly to diet is truly amazing- It’s strange though, I felt my absolute best with my lipids off the charts bad…With my “better” lipids, my energy and mental clarity are good but not quite the same- at least I’m in a known (good) medical state… Thx again for the continued enlightenment!

P Value Insanity

I never knew what a P Value was – when looking at studies – i assummed it was some kind of stasticical pro or con –

I’m sorry I looked up it’s meaning on Wiki – people who get this involoved in this usless crap in manipulating numbers are in sorry need of help or medication or both –

I’m afraid to look up the exact meaning of – The Scientific Method – for fear of further disappointment –

My Critical Thinking has taken a hit just reading about some of this mindless crap –

I suppose my critcal thinking ? is just too stupid too appreciate the fact – that people actully get paid to indulge themseivles in these sorts of activities –

It seems their time would better spent cleaning toilets for the next 20 years until they repented –

Jeff, you’re throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Don’t dismiss statistics because most people misuse or abuse them.

saw the best bumper sticker ever the other day, ” If evolution is outlawed, only outlaws will evolve”

hope this is not off topic, but I think this is one of the best examples critical thinking I’m come across. The argument exercise vs. recreation is elaborated on here- https://www.renaissanceexercise.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Exercise-vs-Recreation.pdf

if anyone can refute any of this I would like to hear it

and thanks for the excellent post, as usual

This is totally inline with recent DNA similarity study 🙂

In short, recent study showed that people are attracted to those with similar DNA. If it is true that we copy external behavior, internals can’t be much different for obvious reasons.

https://plus.google.com/+MiodragMili%C4%87/posts/5WMdbtsWEev