I embarked on a self-experiment last weekend to see if I could better understand the interplay between the different types of exercise I do and ketone production (beta-hydroxybutyrate, or B-OHB, to be specific). To be clear, nothing I do with a sample size of one “proves” anything, but sometimes self-experiments can help you formulate hypotheses and, if nothing else, understand how your body works. Consider the parable of the black sheep. If you see even a single black sheep in the field, depending on your field of training, you can draw conclusions:

Three scientists were on a train and had just crossed the border into Scotland. A black sheep was grazing on a hillside. The biologist peered out of the window and said, “Look! Scottish sheep are black!” The chemist said, “No, no. Some Scottish sheep are black.” The physicist, with an irritated tone in his voice, said, “My friends, there is at least one field, containing at least one sheep, of which at least one side is black some of the time.”

My point is, even a self-experiment of one can be good for something.

To test the relationship between exercise and ketosis I decided to examine my blood levels of glucose, B-OHB, and lactate immediately before and after three different types of workouts on three successive days. This interplay is complex and no one knows “everything” about it, including the world’s experts (which I am not pretending to be). I’m going to try to balance a fine line in this post – I want to be rigorous enough to explore the ideas with substance but not too detailed to put you to sleep. I hope I am able to balance these forces adequately.

If any of you are not familiar with the work of Jeff Volek and Steve Phinney, but you are interested in the biochemistry of nutritional ketosis, I recommend getting familiar with their work. The list of people who know more about nutritional ketosis is short.

Let’s take a look at the three parameters I measured in a bit more detail. To give you a sense of what is “normal” here are some guidelines:

Glucose

A normal fasting glucose is generally considered to be between 75 and 100 mg/dL. My mean over the past year has been about 90, but I need to mention two very important caveats:

- On the four occasions I have calibrated my hand-held device with an actual laboratory test, my device seems to run high by about 11 mg/dL, so a measurement of 95 mg/dL on my device is probably closer to 84 mg/dL in reality.

- I carry a genetic trait for a disease called beta-thalassemia. The clinical manifestation of this is that I have much smaller red blood cells than normal (about 65% of normal size). There is some evidence in the literature that this condition prevents some accurate testing of any assay that can interfere with hemoglobin. For example, a test measuring glycosylated hemoglobin suggests I have much more glucose in my blood than is actually measured. In fact, the Glycomark test for mean post-meal glucose level suggested I have an average post-meal glucose level of 190 mg/dL which is obviously not true. In other words, something about my beta-thalassemia seems to interfere with, at the very least, measuring glucose linked to hemoglobin, and possibly measuring glucose in general.

I mention these 2 features to say my glucose levels (unlike B-OHB and lactate which I’ve documented to be very accurate) may be artificially elevated. Here’s the important part, though: the discrepancy seems to be constant, so the increases or decreases seem to be good measurements.

Beta-Hydroxybutyrate (B-OHB)

A normal fasting B-OHB level for a “normal” (i.e., non-ketotic) person is zero. Within a day of fasting, you might expect this number to reach 0.2 to 0.4 mM, and about 1.0 mM within 48 to 72 hours of complete fasting, though this is highly variable among subjects.

If you’ll recall from my discussion of keto-adaptation, the threshold for nutritional ketosis is about 0.5 mM. My normal morning fasting level of B-OHB is usually between 1.0 and 2.0 mM with an arithmetic mean of about 1.4 mM.

Both insulin and glucose (probably by causing the secretion of insulin) suppress ketones. This is why, for example, consuming more than about 50 gm of carbohydrates per day and/or more than about 120-150 gm of protein per day makes it difficult to be in nutritional ketosis – too much insulin secretion.

Lactate

Lactate (or lactic acid) is a byproduct of anaerobic exercise. A normal level is considered to be below 2.2 mM. Basically (I’m oversimplifying a bit), when you exercise in a predominately aerobic capacity, while you do generate lactate your liver is able to match muscle production with clearance via a process called the Cori Cycle (a process in which the liver turns lactate back into glucose).

If you’ve ever done a very intense exercise – like run an all-out mile – and felt like your body is completely seizing up and you are unable to move, you’ve experienced a high lactate. Technically, the lactate is not causing this. Lactate gets a pretty bad rap, and it’s actually a good thing as it allows us to generate energy even when we demand it in an environment where sufficient cellular oxygen is absent. The real “bad guy” is the hydrogen ion that accompanies lactate and interferes with the ability of our muscles to contract and relax properly. However, we use lactate as a proxy for the hydrogen that is actually causing the pain and difficulty in muscle contraction.

For me (personally, though this is probably true for most people) the highest lactate I generate tends to be in all-out activities lasting about 2 minutes which use all muscles in my body (the more muscles you use, the more lactate you generate). Hence, the 200 individual medley (IM) race generates the most lactate in my body: It’s 2-plus minutes of maximum exertion sending pain into every muscle in my body (this event requires a swim, in order, of 50 yards each of all-out butterfly, then backstroke, then breaststroke, then freestyle). A runner would probably concur that the 800 meter (half-mile) run is one of the most painful races in that sport.

The highest lactate I have ever measured in myself, following a 200 IM race, was about 16 mM. I have measured higher levels in several Olympic swimmers, including 20.2 mM in one (as he was vomiting all over the pool deck – for reasons I’ll try to remember to explain in a subsequent post). On my bike, where I’m mostly using my legs, obviously, I think my highest recorded lactate measurement was about 12 or 13 mM following a set of ten 2-minute all-out hill repeats.

I measure my lactate levels using a different hand-held device from the one that measures glucose and B-OHB.

[Another parable, this time about marriage: 2 years ago my father asked me what my wife and I wanted for Christmas. I said “we” wanted a lactate meter with about 200 test strips (I think it was about $900 for everything). He looked at me funny, but figured I knew what I was talking about. When Christmas rolled around and “we” got “our” lactate meter I had to spend a few minutes explaining to my wife why this was a perfect gift for “us” as it allowed “us” to spend lots of time together while she pricked my finger for blood during my workouts. She didn’t really agree with me. I clearly don’t understand women very well – I really thought she would find this device “cool.” Which is why this is a blog about health, not marriage.]

Results from my experiment

Day 1: Saturday (hard swim workout, race pace)

This was a one hour, 45 minute swim with warm-up and cool down. The “main set” was mostly freestyle and butterfly at all-out race pace for distances of 25, 50, 75, and 100 yard intervals with long rest (1:2 – 2 times more rest than swim time) for the all-out 100 yard swims, and modest rest (2:1 – half the rest time of each swim). The single most demanding aspect of this workout took place with about 25 minutes remaining and, though I didn’t measure peak lactate, I suspect it was around 12-14 mM, based on the discomfort I experienced. I was surprised that my lactate level was still as high as it was (see below) 25 minutes later, though I suspect I didn’t cool down as gingerly as I should have, to optimize for maximum lactate clearance.

During this workout I consumed nothing and prior to the workout I consumed my usual 40 mL of medium chain triglyceride (MCT) oil.

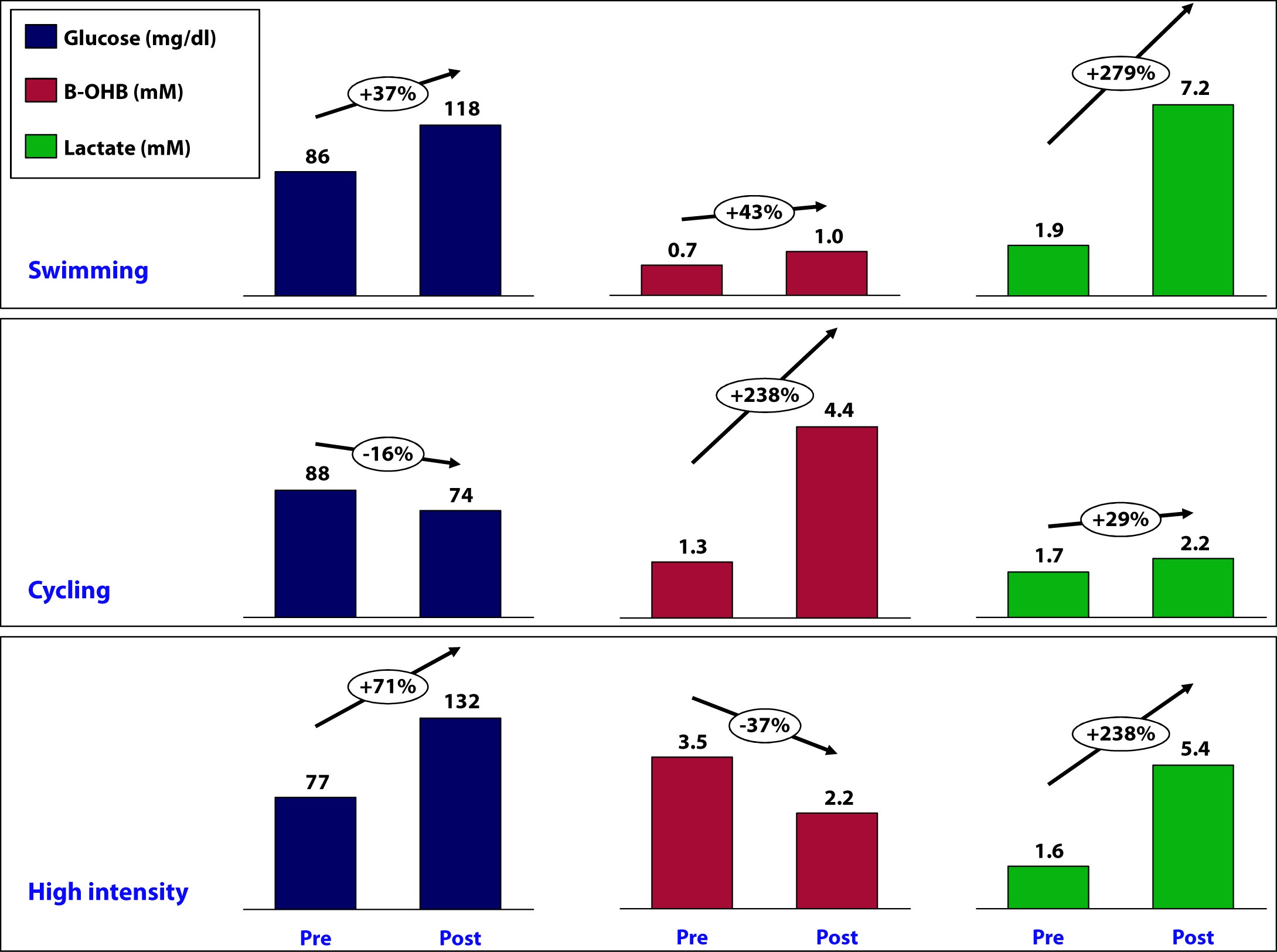

At 7:29 am, just before beginning the workout, my glucose was 86 mg/dL, B-OHB was 0.7 mM (which is low for my fasting level), and lactate was 1.9 mM.

Immediately post-workout, at 9:14 am, my glucose was 118 mg/dL, B-OHB was 1.0 mM, and lactate was 7.2 mM.

Day 2: Sunday (long ride, 80% of race pace)

This was a tempo ride covering 104 miles (167 km) with 5,600 feet of climbing. Average pace was 17 mph (about 28 km/hr) with lots of headwind. My average HR over this 6 hour ride was 141 and average power output was between 190 and 200 watts. There were many sections of the ride, particularly on the climbs, where my HR was sustained in the 160’s for 30 minute stretches and power output was above 275 watts (which, for me, means my muscles generate lactate faster than my liver can clear it).

During this workout I consumed the following:

- Two single-serving packets (1 oz) of cream cheese (14 gm fat; 2 gm carb; 2 gm protein)

- 50 gm of super starch, by Generation UCAN mixed in my water bottles (50 gm super starch which, technically, is a carb but does not behave like one with respect to insulin secretion and ketone suppression – I will write a dedicated post on super starch in the future, but if you must try it now, use this code to get a discount: “UCANPA”)

- 2.5 oz of mixed nuts (25% of each almonds, cashews, walnuts, peanuts – 36 gm fat; 14 gm protein; 15 gm carb)

Total intake during 6 hour ride, therefore, was: 50 gm fat; 16 gm protein; 67 gm carb (of which 50 gm was super-starch), for a total of about 750 calories.

About 90 minutes prior to the ride I consumed 4 eggs fluffed with heavy cream, cream cheese, coffee with heavy cream, and my usual 40 mL of MCT oil.

At 7:56 am, my glucose was 88 mg/dL, B-OHB was 1.3 mM, and lactate was 1.7 mM.

Immediately post-ride, at 2:39 pm, my glucose was 74 mg/dL, B-OHB was 4.4 mM, and lactate was 2.2 mM.

Day 3: Monday (dry-land, high intensity training)

On this particular day, it was raining (one of 3 days a year this happens in San Diego), so I did not do the outdoor stuff (including tire flips).

Prior to the workout I consumed nothing other than my usual 40 mL of MCT oil and during the workout I consumed about 4 gm of branched chain amino acids (BCAA) and 10 gm of super starch mixed in my water bottle – so essentially just water.

Immediately prior to the workout, at 6:43 am, my glucose was 77 mg/dL, B-OHB was 3.5 mM*, and lactate was 1.6 mM.

At 7:52 am glucose was 132 mg/dL, B-OHB was 2.2 mM, and lactate was 5.4 mM.

*If you’re wondering why my fasting B-OHB level was so high (recall, I’m usually between 1.0 and 2.0), I suspect it’s at least a partial result of 2 things:

- Residual fat breakdown from the previous day’s long ride and caloric deficit, and

- On Sunday night I ate (no exaggeration) about half a gallon of my wife’s famous zero sugar, high fat coffee ice cream, which must be the closest thing I’ve ever experienced to heroin in terms of addiction potential.

Summary

The figure below summarizes the data from the mini-self-experiment I just described.

What can we learn about the interaction between glucose, B-OHB, and lactate?

How does super starch impact my ketosis?

Is ketosis helping me or hurting me?

Stay tuned for next week, when I will try to interpret these results…

Photo by James Thomas on Unsplash

Interesting thing about salt. I bonked something bad in the first month of low carb diet because I was not consuming sufficient salt (and probably fluid). I couldn’t stand the taste of bouillon. The only thing that eventually helped the dizziness, headaches and fatigue was a half teaspoon of salt put on the back of my tongue and washed down with a huge glass of water. I am still extremely carb-restricted (<20 g per day, if even that), but no longer need any salt whatsoever. The ketoadaptation process probably takes at least 8 weeks. Get through this hump and it is relatively easy sailing. 33 lbs later….

(PS, I do not exercise. If you exercise, you need to replete your electrolytes and fluid loss – no question)

Excellent self-experiment! That’s really great and exactly what I love to read. Investigating to accurately understand how the body works on a physiological level, and then adapting what we do and eat to optimise health. The results make perfect sense: the higher the intensity, the more stimulation to the adrenals that secrete both growth hormone and stress hormones. The stress hormones suppress lipolysis and stimulate the liver to churn out glucose. Since glucose becomes the primary cellular fuel, lactate concentrations rise. There is a close relationship between the intensity and duration. The swimming intervals are still relatively long, whereas the “dry-land” high-intensity work is really short, and thus that much more intense. Really great stuff! I can’t wait to read the continuation.

I just wrote up the results of my own self-experiment on the effect of dietary cholesterol on its concentration in the blood. I have to say that I kind of knew the answer already from reading it in books, but I wanted to see for myself. Here is it: https://healthfully.wordpress.com/2012/03/09/six-eggs-per-day-for-six-days

The correlating increase in glucose and lactate and the decrease in B-OHB is not surprising to me in HIT. It would be interesting to know your level’s B-OHB 1, 2, 3, etc. hours post workout while your glycogen stores where empty.

I have never tested it, but my breath (according to my wife) does seem to be a bit more ketotic 1 and 2 hours after a Tabata bout.

Peter, I have just recently discovered your blog. I find it really interesting. I have just started low carb two weeks ago and I’m training for a half ironman in August. I am also a Type 1 diabetic. My question is in regard to workout and race fueling. Is this your typical fuel for a 6 hour endurance workout? Would I have to be in ketosis to follow such a plan or would you suggest starting now to allow my body to adapt?

Yes, this is typical for me. If I was non-ketotic low-carb, I would likely be less dependent on fat, but still more metabolically flexible than a “normal” person. Because of your T1D, it’s going to be a bit more work, but still very doable. You must check out the site A Sweet Life and contact Mike Aviad (https://asweetlife.org/contributors/michael-aviad/). Mike is T1D and a marathoner. He’s also very low carb.

I have 2 general questions about the relationship between insulin/ketosis/weight loss.

1.) Is it possible to be in ketosis and not lose extra weight?

It seems most of the theories behind low carb diets failing to produce weight loss have to do with insulin response being caused by other stimulus (cephalic response), or hidden carbs.

2.) If this were the case, would the insulin response take a person out of ketosis, or decrease ketone levels?

Unsurprisingly, this question has a personal motivation. Since I’ve begun carb restriction I’ve felt better- more energy, no more low blood sugar issues. However, I haven’t lost any really noticeable weight. I’m not actually overweight, but I know I have a bit more flesh than I did in my 20’s, so I’m sure I have some to spare. I’ve measured my ketones and they are always between 40-100 mg/dl per keto-sticks. I always appreciate your feedback. Thank you for taking the time to answer my/other readers questions.

1. Yes you can be in ketosis and plateau in weight (like I have been for many months).

2. For many people, being in ketosis is a “leaner” state than not being in ketosis, but not necessarily for everyone.

It can take a while for your body to begin to mobilize our fat stores. But you said the most important thing yourself…you FEEL better. Body composition is but one part of it.

Do you know a good resource for understanding the basic biochemistry of the body in ketosis? I guess I was really wondering, if there is insulin over-secretion for someone in ketosis, what happens? Does it decrease ketone levels? Scavenge blood sugar? People in ketosis still have ambient levels of blood glucose, where does it come from? Is it continually being used then replenished from gluconeogenesis, or simply recirculating and conserved? I’m afraid a biochemistry textbook is too basic, but I’m also not sure I want subscribe to a bunch of journals to get overly specific concepts explained. Or… is there even such a resource? Has the research been done?

The book by Phinney and Volek in my books & tools section.

If you think of nutritional ketosis as helping you lose excess body fat, I think it may help you understand the process better. I’ve been in ketosis for several months but haven’t lost any additional weight. I’m leaner than I’ve ever been. I think after a while, you reach a point of equilibrium because your substrate level (fat) is so low.

Peter:I have been on a low carb diet modeled after your diet for the last few months and decided to have a blood test taken to assess the diet. I was shocked to see my glucose was 105 when it generally has been in the low to mid 90’s. Any idea what I’m doing wrong?

Most of my blood lipid were up. My VAP test showed my LDL at 145, my total cholesterol was 249, Lp(a) 0f 15, and a positive HDL 0f 92.

My triglycerides were normal at 48.

What do you think I’m doing wrong? I feel great but these results confuse me. Should the increase in blood lipids concern me? I am a 64 year old runner who is not overweight.

I’m just looking for your opinion and and feedback. Any suggestions will be helpful. Many thanks!

Bobby, I can’t comment on personal medical questions on a blog. But I can tell you that a VAP is of very little value. There numbers actually tell me very little about your risk. You need an NMR to count LDL particles and HDL particles. The only thing I can see from this is that your TG to HDL-C is very favorable, but no idea what your risk is without know LDL-P and HDL-P. I’ll do some serious writing about this in the (near, I hope) future.

Peter: I understand that you can’t comment on my personal medical questions. As a general question, not specifically about me, why would an individual on a low carb diet see an increase in blood glucose?

This would be unusual, but there are countless factors that could contribute to it (previous meals, degree of fasting, accuracy of measurement, etc.).

Any comments about the latest LA Times article that’s floating around about any amount of red meat increasing your risk of dying earlier: https://www.latimes.com/health/la-he-red-meat-20120313,0,565423.story I know that correlation is not causation, but have you by any chance looked at this study specifically (or know someone who has?).

I’ll address in the detail in next week’s post. Quick answer on my FB page.

I love that the claim is that eating red meat is associated with higher death rates from ALL CAUSES. This study tells us that beef-eaters are more likely to get hit by falling pianos!

Thanks for you great self experimentation.

I am on a similar journey.

I believe that part of what you saw for your high morning B-OH after your Day 2 workout may have been attributed to the UCAN SuperStarch. If you look at the data from their OK study you will see that they only followed fat oxidation for 90 minutes during the recovery phase,however, not only was it significantly higher than using maltodextrin for recovery it was also separating in magnitude indicating the potential for more fat oxidation (fuel) utility during recovery and continuing long after. What do you think?

Will you retry this study with a change in the testing order? Start with the high intensity and move to the bike or start with the bike and finish with the swim? I know there are several permutations but you may find the answer to the swim influence on the B-OH or perhaps you should use UCAN for each workout.

Keep playing.

Regards

sheri

Thanks, Sheri. It’s possible, for sure. The experiment I’d like to do next is ingest the same amount of super starch while sitting at the computer and see how it impacts ketosis.

I have searched through 3 pages, 148 comments, for the coffee ice cream recipe.

I cannot find the ice cream recipe.

I left it on March 7.

Heh-heh; and here I thought the entire point of Life in Ketosis to begin with is precisely so I could STOP doing painful, boring, senseless forced exercise. What was I thinking? 😉

What device do you use to measure your B-OHB concentration?

See link in this post.

Are you paying $5/each for ketone strips?

No, I pay less, typically, but they aren’t cheap. Good thing I don’t spend money on cigarettes 🙂

Hello Pete,

Outstanding Blog! Thank You! I was debating a nutritionist with extreme high credentials. When I told her I was in ketosis she never fell over! She told me I was damaging my brain and body. I can’t tell you my frustration, because nutritionist tend to fall back on the statement that “ketosis is bad for you body and brain”. How would you response to someone that is convinced ketosis is dangerous?

Check my FAQ: https://eatingacademy.com/nutrition/is-ketosis-dangerous

I get this question all the time…

Hey, Peter.

I’ve been training in ketosis for a couple of months now. Just in the last couple of weeks, based on your advice, I’ve upped my fat and lowered my protein from 160 to a little over 100 grams. It’s accelerated my weight loss.

One problem I’ve had in the past on carb restriction in working out at the gym or running, was becoming light headed and feeling like I might faint. I assumed it was only attributable to low glycogen stores. I’ve added three grams of sodium daily, and there is a world of difference in both my endurance and how I feel. Normally after a long run, I feel like hammered shit, but I felt good this week even after a three-hour run. It’s also the first time I’ve run past two hours without consuming any carbs during the run, and I felt great. It’s really a stunning difference.

One book I saw mentioned here in the comments was Phinney’s and Volek’s “The Art and Science of Low Carb Performance.” I bought it, and it covers everything. You should put that in your “Books and Tools” section.

Also, your ice cream recipe is better with coconut milk. The kind in the dairy section next to the almond milk, not the canned stuff. The fat gives it a creamery consistency. My wife, kid and I preferred it to the almond milk version. Plus, you get the added benefit of MCTs mixed in. Give it a shot!

Mark, I’ve got their book, but I haven’t read it yet. Will get it up there when I do so. Look forward to trying the coconut milk idea. Are you substituting it in for the cream or the almond milk?

I substituted for the almond milk. I liked it with both, but I think the coconut milk version came out better. Here in Atlantic Canada, we have two brands: Silk and So Delicious. The So delicious brand doesn’t have a strong coconut flavor. I’m not sure if these brands are available across the whole U.S.

Hi Peter, first off great blog, this is exactly what I was looking for. I’m a low-carb endurance athlete (aspiring triathlete) and I’ve been looking for others out there who are training at a high level on a ketogenic diet. I’ve recently decided to give strict ketogenic a try. (before I had been floating around 50-100g carbs per day, with larger amounts after intense or really long workouts).

I was very intrigued after hearing about Superstarch and its negligible insulin response. It seems like as you’ve said, this could be the key to allowing higher intensity glycolytic efforts while remaining ketogenic. I was wondering if you use superstarch at any time other than during your very long bike workouts to replenish glycogen? For example, do you ever take in any after a very intense lifting session or swim in the 1-2 hour range?

I know you are planning on writing a dedicated post on Superstarch, so if you’d rather wait util then to address these kinds of questions then I understand. I’m looking forward to that post.

Thanks for all the great information!

-Chris

I’ll definitely write about this in the future, but you should definitely experiment with it around various types of workouts (type, intensity, duration).

I love your blog and all the information, but I do translate some of it into “better nutritional forms” as I read it. For instance, here’s a recipe for homemade bouillon https://nourishedkitchen.com/homemade-bouillon-portable-soup/ that has to be nutritionally superior to commercial varieties. Think source of your food half as conscientiously as you measure your electrolytes — you eat good meat, right?

And then the coconut milk varieties in the refrigerated section — you have to read their list of ingredients as well. Too processed, and I’m planning on making your ice cream recipe (when I have a party and it won’t be sitting around), I wonder if the real – canned – coconut milk can be modified somehow.. I’ll let you know if it’s any good.

Think food quality!

Oh yes, homemade bouillon is much better. It’s a trade-off.

What is the metabolic necessity for carbohydrates? Why must one eat a minimum of say 30g of carb per day? There must be some process that simply cannot be entirely fueled by ketosis in order for there to be a minimum required. My supposition is that a person who has 50 pounds of excess fat could not live for 100 days with no carbs at all.

i am a type one insulin dependent diabetic of 52 year duration…. if my blood sugar level drops low enough i would bet that i would pass out no matter how strongly into ketosis i had gone… i do not believe beta hydroxybutyrate in very high availability could prevent this, am i wrong???

If B-OHB levels are high enough (3-5 mM), one can tolerate BG levels below 30 mg/dL, but as a T1D, it’s a very delicate balance and not worth playing with.

I am pretty tolerant of low BS. At 50 I feel no change at all. While bicycling, for instance, I will only discover that it is 50 due to routine test before an insulin injection. At around 35 to 40 my wife says that she can tell a difference in me although I don’t always notice it. The lowest level I have tested at was 20. I definitely knew something was amiss but was still well enough together to run the test twice because I questioned it. From the feelings I have experienced I am pretty certain that I could not tolerate a level of 10 but perhaps I am incorrect? Is it literally POSSIBLE to have a BS reading of say 4 or 5 and remain conscious if the B-OHB is say 5 or even 6? My interest is merely academic and I would never attempt to get to these sorts of readings in other than a clinical environment.