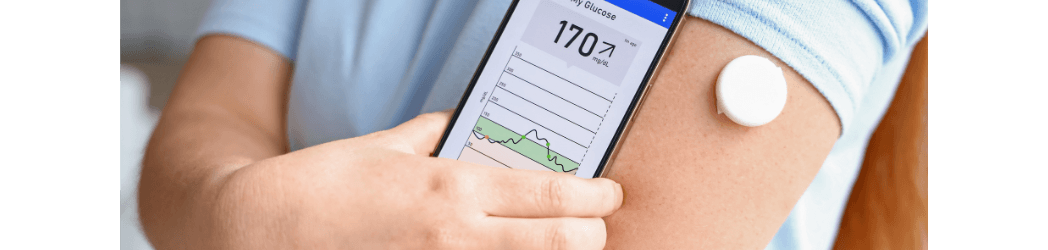

Impaired blood glucose control is one of the classical and most deleterious elements of metabolic syndrome (recently discussed at length in AMA #51), and thus, tools for monitoring blood glucose levels provide important information about metabolic health. One such tool is continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), in which a subcutaneous sensor measures glucose levels at regular intervals (e.g., every five minutes) from dermal interstitial fluid, which closely mirrors the levels of glucose in blood. Given the importance of glycemic control in managing diabetes mellitus, CGM technology is widely used among diabetics and pre-diabetics, but as a recent review has pointed out, even those in evidently good metabolic health may benefit from the use of CGM.

A tool for monitoring glucose dynamics

Even in non-diabetic individuals, glucose regulation is highly variable from person to person, with some individuals exhibiting far more dramatic swings in blood glucose throughout the day than others. Indeed, previous research by Hall and colleagues has led to the proposal of distinct “glucotypes” based on different patterns observed in glycemic responses among non-diabetic individuals.

CGM is particularly useful in monitoring such glucose dynamics, especially with regard to postprandial hyperglycemia – the glucose elevations experienced in response to food consumption. (Optimally, blood glucose levels should peak around an hour after eating, reaching maximal levels of around 140 mg/dL, and should return to baseline levels within two or three hours.) Unlike single measurements of blood glucose or hemoglobin A1c, CGM can track how glucose levels are changing over time, including in response to meals, sleep, and exercise, etc., and these patterns can be clinically significant. For instance, in the Hall et al. study cited above, those with a glucotype associated with the largest fluctuations in blood glucose – roughly 24% of all normoglycemic participants tested – were found to spend roughly 15% of their time (over a 2-4 week test period) with glucose levels exceeding the threshold for prediabetes, demonstrating how even those considered metabolically healthy can have subclinical metabolic dysregulation that would likely be missed by a one-time blood glucose measurement.

The magnitude of glucose swings is related to health

Many health benefits are associated with fewer and more modest glucose excursions, including reduced cardiovascular disease (CVD), oxidative stress, and inflammation. In a large study, non-diabetic individuals in the highest 20% of postprandial glucose responses had a 2.7 times greater risk of CVD-related mortality over 20 years. Elevated blood glucose is also associated with endothelial cell dysfunction and oxidative stress even in non-diabetic people. Importantly, in this study, the authors demonstrated that greater oscillation in glucose levels was more closely associated with these negative effects than higher average glucose level, underscoring the importance of understanding the individual variation in blood glucose following meals. More dramatic glucose dynamics are also associated with higher body weight and BMI, as well as higher self-reported hunger and calories consumed in subsequent meals.

Using CGM data to attenuate glucose swings

Simply being aware of glucose excursions may be useful in detecting subclinical metabolic disease, but the rapid feedback provided by CGM also allows us to determine what triggers dramatic glucose swings, which in turn can help us to make dietary or behavioral changes to avoid such excursions in the future. This offers health advantages even for individuals without any evidence of metabolic disease and is particularly important for individuals over the age of 60, who begin to have slightly elevated glucose levels even at rest and spend significantly more time with glucose above 140 mg/dL than younger people, leading to increased risk of multiple poor health outcomes.

Of particular importance in ensuring reduced glucose excursions and oscillations is the modification of diet. Generally speaking, a high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet results in greater spikes in blood glucose than a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet, suggesting that altering the ratio of carbohydrates and fats consumed significantly impacts postprandial hyperglycemia. However, glycemic responses to specific foods can vary on the level of the individual and in response to a number of other variables such as hormone status, meal timing, stress, sleep quality, and activity level. Thus, real-time data from CGM can be a valuable tool in identifying one’s own dietary triggers as well as other modifiable behaviors that might contribute to more dramatic glucose spikes.

Another benefit associated with CGM is improved sleep quality. One study showed that sleep duration is negatively correlated with blood glucose, as measured by CGM. Giving people the ability to monitor and lower their bedtime blood glucose concentrations could thus improve sleep quality. This is particularly important because sleep is also known to influence postprandial glucose response the following day. Specifically, poor sleep and later bedtime are associated with more dramatic postprandial hyperglycemia response the following morning. Ensuring high quality sleep by controlling nighttime blood glucose would result in better next-day blood glucose responses, demonstrating the particular importance of sleep in glucose control.

Beyond diet and sleep, exercise is also known to influence blood glucose, as multiple studies in healthy individuals have shown that exercise after a meal blunts the hyperglycemic response. Exercise is also known to improve the body’s response to high glucose levels at the level of improved cellular uptake.

CGM data can modify behavior to improve overall health

CGM feedback on glycemic responses can motivate changes in behavior that benefit health in ways that extend beyond the blunting of glucose dynamics. For instance, nearly half of healthy CGM users in one study reported high glucose levels increased their likelihood of a subsequent walk or physical activity, and increased physical activity in turn has numerous positive impacts outside of glucose control, such as improvements in cardiovascular and cognitive health.

One important caveat is that in younger, healthy individuals, the long-term use of CGM may not be valuable. Short-term use may be helpful in understanding one’s own personal glucose response curves and triggers of glucose spikes and would thus help to inform future dietary and behavioral choices. However, in individuals who do not have either diabetes or pre-diabetes, health insurance does not cover the use of CGM, such that after the initial weeks or months of use, the cost of using CGM may offset the knowledge gained. (For more information on all things blood glucose, including CGM use in non-diabetics, check out AMA #24.)

Toward more personalized approaches to health

Though we know that diet and exercise are important for reasons beyond the control of blood glucose, the use of CGM to inform specific dietary and exercise recommendations may help to serve as a tool for a more personalized and optimal approach to medicine, since general lifestyle recommendations are rarely “one-size-fits-all.” Considering the information above, it’s clear that CGM is a potent tool even in people without diabetes mellitus and offers patients the ability to monitor their own glucose data in order to take a more active role in their healthcare and disease prevention.

For a list of all previous weekly emails, click here.