In a word, yes. But, technically this is the wrong question.

The correct question is probably closer to, “What is the impact of the calories I consume on my body’s ability to store fat versus burn fat?”

The immediate follow-up question to some variant of this first question is, “Should I be counting calories?” In a word, no. But you’ll want to read this post fully to qualify that answer.

Before I answer these important questions, let’s spend a few moments reviewing five key concepts.

Key concept #1 – the definition of a calorie

A calorie is a unit of measurement for energy content. By formal definition a calorie is the amount of heat energy required to raise one gram of water from 14.5 to 15.5 degrees Celsius at atmospheric pressure. One-thousand calories is equal to 1 kilocalorie, or 1 kcal for short. Here’s where it gets a bit tricky. Most people use the term “kilocalorie” and “calorie” interchangeably. So when someone says, “a gram of fat has 9 calories,” they actually mean 9 kcals. The important thing to remember is that a calorie (or kcal) tells you how much energy you get by burning the food. Literally. In the “old days” this is how folks figured out the energy content of food using a device called a calorimeter. In fact, to this day this is how caloric content is measured when doing very precise measurements of food intake for rigorous scientific studies. As a general rule carbohydrates contain between 3 and 4 kcal per gram; proteins are about the same; fats contain approximately 9 kcal per gram.

[If you’re wondering why fats contain more heat energy than carbohydrates or proteins, it has to do with the number of high energy bonds they contain. Fats are primarily made up of carbon-hydrogen and carbon-carbon bonds, which have the most stored energy. Carbs and proteins have these bonds also but “dilute” their heat energy with less energy-dense bonds involving oxygen and nitrogen.]

Key concept #2 – thermodynamics primer

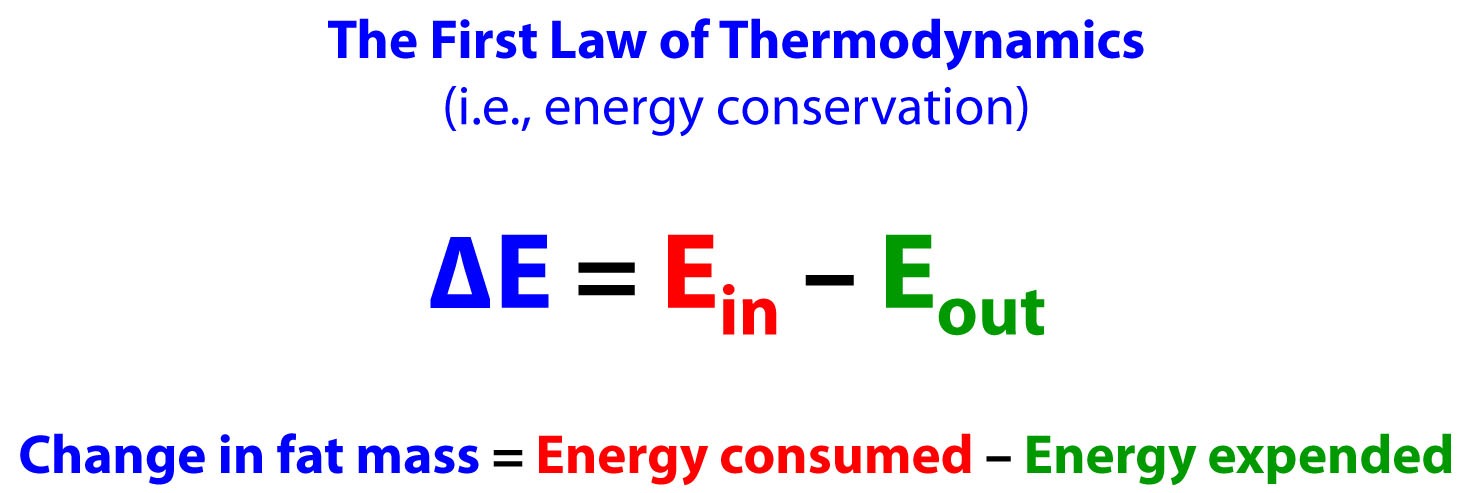

It might be a good time, if you haven’t done so recently, to give a quick skim to my previous post, revisit the causality of obesity. In this post I review, among other things, how the First Law of Thermodynamics explains fat accumulation and loss. To reiterate, the First Law of Thermodynamics says that the change in energy of a closed system is equal to the energy entering the system less the energy leaving the system. When we apply this to fat accumulation, it looks like this:

People like me (and others) get a bad rap from folks who lack the patience (or training, perhaps) to actually hear the entire argument through before throwing their hands in the air, waving them frantically, and screaming that we’re violating the First Law of Thermodynamics for asserting the Alternative Hypothesis (more on this below).

Let me be as crystal clear as possible, lest anyone feel the need to accuse me of suggesting the Earth is flat. The First Law of Thermodynamics is not being violated by anything I am about to explain, including the Alternative Hypothesis.

Key concept #3 – current dogma

Conventional wisdom, perhaps better referred to as Current Dogma, says that you gain weight because you eat more than you expend. This is almost true! To be 100% true, it would read: when you gain weight, it is the case that you have necessarily eaten more than you expended. Do you see the difference? It’s subtle but very important — arguably more important than any other sentence I will write. The first statement says over-eating caused you to get fat. The second one says if you got fat, you overate, but the possibility remains that another factor led to you to overeat.

If you believe Current Dogma, of course you’ll believe that “calories count” and that counting them (and minimizing them) is the only way to lose weight.

Key concept #4 – the rub

Most folks — but not all — who subscribe to Current Dogma do so, in part, because they don’t appreciate one very important nuance. In the equation above, explaining the First Law of Thermodynamics, they assume the variables on the right hand of the equal sign are INDEPENDENT variables.

Let me explain the difference between independent and dependent variables for those of you trying to suppress any memories you once had of eigenvectors. As their names suggest, independent variables can change without affecting each other, while the opposite is true for dependent variables. A few examples, however, are worth the time to make this easy to understand.

- The weather and my mood are dependent variables. When the weather goes from gloomy to sunny my mood tends to improve as a result of it, and vice versa (i.e., when the weather goes from sunny to gloomy, my mood goes from good to bad). In this case the dependence is only one-way, though; my mood changing has no impact on the weather.

- My countenance and my interaction with people are dependent variables. When I smile it seems to cause a more positive interaction with the people around me. Similarly, when I’m having a good interaction with someone I tend to smile more. In this case the dependence goes both ways.

- My height (while I was still growing) and my hair length are independent variables. Both of these variables can change without any impact on each other.

How does this tie into the idea of the First Law? Let’s re-write the First Law with a bit more specificity:

The change in our fat mass is equal to what we eat and drink (the only source of energy entering our system) less all of the energy we expend.

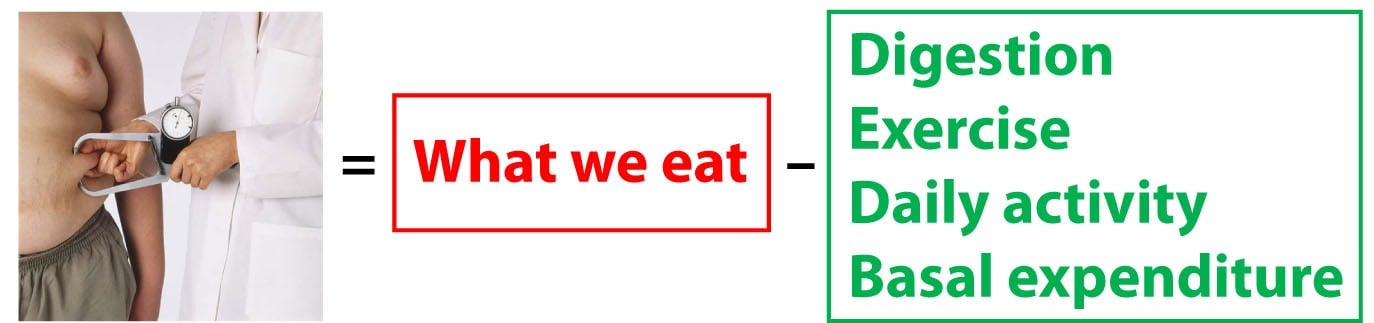

Now let’s be even more specific on the “expend” part of the equation. We expend energy in four ways: Digestion (all the energy we require to break down food, plus the undigested portions that leave our body); Exercise (everyone knows what this is, but I tend to separate it from daily activity since people really like to focus on exercise); Daily activity (the non-exercise activity we carry out); Basal expenditure (the energy we expend “underlying” any activity – e.g., when you are resting).

Let me clarify something before going further. There are several ways to enumerate and account for our energy expenditure. I happen to do it this way, but you can do it other ways. The important thing is to make sure that you are collectively exhaustive when doing so (and mutually exclusive if you want to make your life easier – we call this MECE, pronounced “mee-see”).

The First Law is only valid when you consider ALL of the energy entering and leaving the system (i.e., your body).

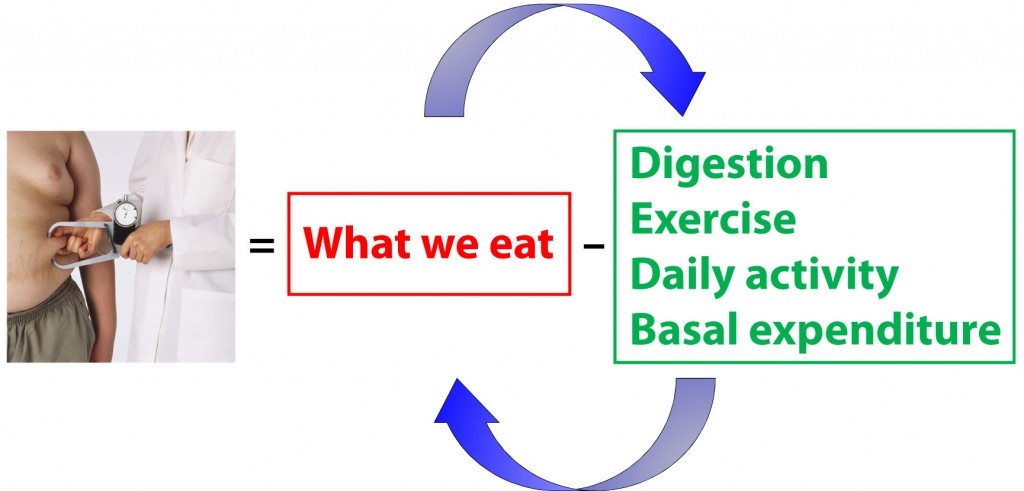

Back to the independence versus dependence issue for a moment. If you look at the equation above, and believe the red box has no impact on the green box, and vice versa, you are saying that energy input and energy expenditure are independent variables. However, this is not the case, and that is exactly why this problem of energy balance is so vexing. In fact, the figure below is a more accurate representation of what is actually going on (and even this is a gross oversimplification for reasons I will mention shortly).

What you eat actually changes how you expend energy. Similarly, how you expend energy changes what (and how) you eat. To be even more nuanced, what you eat further impacts what you subsequently eat. As you increase (or decrease) in size, this impacts how you expend energy.

So there are actually a whole bunch of arrows all over this diagram (I’ve only shown 2: what you eat impacting how you expend, and vice versa. If I included all of the arrows, the diagram would get out of control pretty quickly).

I’m not telling you anything you don’t already know, even though it may sound like it for a moment. When you exercise your appetite rises relative to when you don’t exercise. When you eat a high carb meal you are more likely to eat again sooner compared to when you eat a high fat/protein meal due to less satiety.

Key concept #5 – the Alternative Hypothesis

If, like me, you don’t subscribe to Current Dogma, you’d better at least have an alternative hypothesis for how the world works. Here it is:

Obesity is a growth disorder just like any other growth disorder. Specifically, obesity is a disorder of excess fat accumulation. Fat accumulation is determined not by the balance of calories consumed and expended but by the effect of specific nutrients on the hormonal regulation of fat metabolism. Obesity is a condition where the body prioritizes the storage of fat rather than the utilization of fat.

Why is this different from Current Dogma? Current Dogma says it doesn’t matter what you eat, it only matters how many calories that food contains. If you eat more calories than you expend, you gain weight. The last part is true, but the first part is not. The Alternative Hypothesis says it DOES matter what you eat and for reasons far beyond the stored heat energy in the food (i.e., the number of calories).

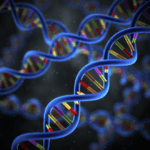

Let me use an example to illustrate this. Consider the following table of various substances known to contain a lot of stored energy. The table shows their energy content in units we usually use to describe energy density, kilojoules per gram (middle column), and I’ve converted to units we typically only use for food energy, kcal/g or “calories” per gram, (right column). [Here we need to be very clear to distinguish between a technical calorie and a kilocalorie, which is almost always what we mean.] A kilojoule is about 240 calories (not kilocal), so 1 kj is about 0.24 kcal, and therefore 1 kj/g is about 0.24 kcal/g.

I’ve highlighted, in bold, four rows of things we typically eat: fat (olive oil, to be specific) with about 8.9 kcal/g; ethanol with about 7.0 kcal/g; starch with about 4.1 kcal/g; and protein with about 4.0 kcal/g.

I’ve also included in this table some other substances known to contain chemical energy such as liquid fuels (e.g., gasoline, diesel, jet fuel), coal, and gunpowder. Hard to imagine a world without these chemicals, for sure.

A quick glance of the table, which I’ve ordered from top to bottom in terms of caloric density, would suggest eating olive oil would be more “fattening” than eating starch since it contains more calories per gram, assuming you subscribe to Current Dogma.

But that same logic would also suggest eating coal would be more fattening than starch and gunpowder less fattening than ethanol. Gasoline would be more fattening than jet fuel. Hmmmm. Anyone interested in testing this hypothesis (personally)? Despite my wildest self-experiments, this is one self-experiment I’ll pass on. Why? Well for the same reason you’d pass on it – you know that there are far more important consequences to drinking diesel or snorting gunpowder than their relative energy densities.

Sure, everything on this list is an organic molecule largely composed of the following four atoms: carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen. Not to bore everyone with a lesson on organic chemistry, but it’s the actual bonds between these atoms that are responsible for their energy densities. When you “liberate” (i.e., break) the bond between an atom of carbon and hydrogen, for example, you release an enormous amount of stored chemical energy. This table tells you exactly how much energy you would release if you were to break the bonds in these molecules, but that’s all it tells you. You can’t actually know, just by looking at this table, if jet fuel is more paraffinic than diesel or if gasoline has more isomerization than propane. And, you certainly have no idea, from the information contained in this table, of exactly how each of these substances will impact the hormones, enzymes, and cell membranes in your body if you ingest them.

Is it relevant to our bodies that olive oil has about the same energy density (i.e., calories) as biodiesel (also known as fatty-acid methyl-ester)? Or, is it more relevant to us that consuming olive oil has a very different effect on our bodies than consuming biodiesel beyond anything to do with the calories contained within them? Obviously consuming equal caloric amounts of olive oil versus biodiesel will have a very different impact on our body. Why then is it so hard to appreciate or accept that equal caloric values of olive oil and rice could also have very different impacts on our body?

The upshot

Let’s get back to the question you actually want to know the answer to. Do calories “matter”, and should you be counting them?

Energy density (calories) of food does matter, for sure, but what matters much more is what that food does in and to our bodies. Will the calories we consume create an environment in our bodies where we want to consume more energy than we expend? Will the calories we consume create an environment in which our bodies prefer to store excess nutrients as fat rather than mobilize fat? These are the choices we make every time we put something in our mouth.

Our bodies are complex and dynamic systems with more feedback loops than even the most elaborate Tianhe-1A computer. This means that two people can eat the exact same things and do the exact same amount of exercise and yet store different amounts of fat. Does it mean they have violated the First Law of Thermodynamics? Of course not.

Similarly, genetically identical twins can eat different macronutrient diets (i.e., differing amounts of fat, protein, carbohydrates) of the same number of calories, while doing a constant amount of exercise, and accumulate different amounts of fat. Does this violate the First Law of Thermodynamics? Nope.

What you eat (along with other factors, like your genetic makeup, of course) impacts how your body partitions and stores fat. In case anyone is wondering how I got over 2,000 words into this post without mentioning the i-word, wonder no longer. Insulin, while not the only factor involved in this process, is probably at the top of the list. When you eat foods that have the double whammy of increasing insulin levels AND increasing your cell’s resistance to insulin, your body prioritizes fat storage over fat utilization. No one disputes that insulin is the most singularly important hormone for causing fat cells to accumulate fat. Somehow the dispute centers on what causes people (full of billions of fat cells) to accumulate fat.

All calories are not created equally: The energy content of food (calories) matters, but it is less important than the metabolic effect of food on our body.

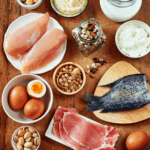

Photo by Aaron Barnaby on Unsplash

I’ve been trying to navigate through your blogs to find this answer, so I apologize for these possibly dumb questions:

1. Is there a continuum of benefits (of any kind: insulin sensitivity, weight loss, trig reduction, etc) seen from a continuum of CHO reduction?

2. Does the source of CHO matter? I saw your graphs from your ‘personal journey’ blog (how you gradually reduced CHO and your bloodwork associated with each stage). But while I’m getting that you say a calorie is NOT a calorie, is a carb NOT a carb? Or is a carb is a carb is a carb?

3. I also saw a response in one of your question and answer sections: Q:”Is ketosis for everyone?”. And you said something like “definitely not”. How does one know if they should try it? It seems like quite a challenge for most people.

Thanks for your work on these topics.

Jessica,

Hopefully Peter will jump in with his thoughts. Here are some of mine: First, remember that individuals vary a great deal.

1.I don’t see a ‘continuum’ of benefit from reduced carbs, but more like ‘steps/stages’ which can provide benefit. For example, cutting out sugar; cutting out grains and other starchy foods ( low carb); ketogenic (very low carb).

2.If the person has any signs of insulin resistance/ carb intolerance/ blood sugar fluctuations, then I think the source of carbs matters (as well as the quantity). Rapidly absorbed carbs (sugar/ corn syrup, etc) have a negative impact compared to the carbs in something like broccoli/cauliflower/cabbage.

3. For many people getting into and staying in ketosis is harder than low carb; so whether you should try it really depends on your personal situation…what do you want to improve? Do the benefits that people report match your goals?

I’ve been doing low carb for almost two years. I started out gradually, using “Life Without Bread” as my initial guide. I did a lot of reading. I gradually moved my carb count down; using “The New Atkins for a new You” , “The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Living”, and “Primal Body Primal Mind” as guides.

I’ve lost 60#, going from 230# to 170#, and have observed a number of health benefits.

I’ve tried and gotten into ketosis (barely) twice before now; blood ketones generally in the 0.5 to 1.0 range, but occasionally dropping below 0.5. The first time I stopped because I like to do multi-day hiking/pack trips. I had not figured out how to stay ketogenic using dehydrated foods. The second time was traveling and again having trouble with not having the right foods on hand.

I don’t have it all figured out yet, but I’m finding that I need to not only eat very low carb, < 20 grams of net carbs, but also moderate protein, < about 80 grams, with only a small part of that coming from dairy protein, and not too much of the daily protein allotment at any one meal.

I’ve been on a ketogenic diet again the last two weeks. I’m having more success this time…primarily by getting my fat intake up. This has moderated my appetite, so it’s fairly easy to keep the protein down. What I’ve changed about my fat intake is adding a cup, or two, of ‘fat’ coffee/decaf a day (with a generous amount of coconut oil & heavy cream). I’m also putting more butter on vegetables, pouring the ‘drippings’ from cooking meat, over the meat when I serve it, and things like that.

In comments under Dr Attia’s blog “Ketosis – advantaged or misunderstood state? (Part I)”, there was a comment about using a ketogenic adjunct such as coconut oil, MCT oil, or AAKG (Arginine alphaketoglutarate). I had not heard of AAGK before…so googled it. There’s not a lot of info available…much of it is related to AAKG being sold as a supplement for strength training and fitness. I found enough bits & pieces to decide to buy some AAKG and give it a try. I’ve been using it in a ‘keto broth’…broth with coconut oil, heavy cream, and 1 scoop (2 grams) of AAKG. I’ve been drinking it 3 times a day. To me, it has a somewhat tangy/ lemony flavor…I like it. It seems to boost my ketones 0.5 to 1.0 above what they would otherwise be. I think this has also helped me get into ketosis…with ketone readings in the 2.0 to 2.5 range, where 1.0 was as high as I’d gotten before.

It has been a challenge, but for me it’s been worth it. I’m sleeping better, and have noticeably more energy. And, the minimal hunger has made it relatively easy to stay with the diet, once I figured out what to eat/drink.

Is carb resistance the same as inulin resistance?

No, but they are related. IR is a very complex state and involves many organs. One can have IR at the levels of different cells (liver, fat, muscle, neuron).

Do you use carb resistance and insulin resistance interchangeably? People who insulin sensitive aren’t prone to weight gain, but I saw in a comment that you said that someone who couldn’t gain weight was carb resistant. Is it that people who are deemed insulin sensitive are actually insulin sensitive on their muscles cells but not their fat cells?

Hi Dr. Attia

I fully support you and your efforts. I wanted to tell you that most poeple are applying a closed system equilibrium thermodynamic approach to humans . I have spoken to some of the very best biophysics professors from Oxford, Caltech and Cambridge and what they told me is this:

*The human body is an open system

*The human body is a non- equilibrium system

And because of these two facts, this makes the situation hellishly complex to the maximum. If we could evben come up with some equation- it would not be singular. It would be many equations. None of the scientists I talked to could even give me a rough idea of what this might look like and admitted as much. These are top minds too.

We have to consider free energy ( which includes entropy) rather than energy. This area of thermodynamics is extremely subtle.

Nobody mentions the sun either. or skin temperature, or the fact we excrete energy.

I have it on top authority that fat and muscle gain and loss have to do with extremely complex physiological and biochemical processes- it’s not a basic thermodynamics problem. These were the words of the scientists.

Best Wishes,

Raz

Thanks, Raz. All of these can be measured in sum (though not necessarily in isolation), via indirect calorimetery or even doubly labeled water. So I don’t disagree with your point, but it doesn’t change my argument. My point is that something other than *only* caloric balance can drive fat accumulation, *and* this does not violate the First Law. I could not agree more that the First Law is a meaningless way to think about physiology. It’s obvious, and it adds no value.

Peter –

You said: “Similarly, genetically identical twins can eat different macronutrient diets (i.e., differing amounts of fat, protein, carbohydrates) of the same number of calories, while doing a constant amount of exercise, and accumulate different amounts of fat.”

Are you speculating here or are there controlled studies that support this?

I don’t think this exact experiment has been done, though slightly less interesting variants have. It would be a very elegant experiment, and we have discussed it in great detail.

Peter,

I have been following the VERY low-carb approach for a while now. I feel good, the circumference of my waist definitely went down and my blood markers are excellent.

My question; although my fat deposits appear to have gone down a lot, I still have fat around my abdomen that I’d like to lose.

My nutrition is mostly ONLY FAT and PROTEIN (except for some sauerkraut here and there). Reading your blog I realize my problem may be I am intaking TOO MUCH PROTEIN.

I wonder if I may also be intaking TO MUCH FAT, and thus my body is not burning abdomen fat?

In order TO BE LEANER while on a FAT-&-PROTEIN-ONLY diet, how does one know if it is PROTEIN ONLY or FAT ONLY (and by HOW MUCH) that needs to be cut out?

I guess I mean, WHEN IT COMES TO BEING LEAN, is it not only a matter of LOW CARB BUT ALSO CONTROLLED CALORIES (meaning does the amount of calories matter when it comes to being lean)?

Thanks a lot for a lot for the effort to share the information in this blog.

I continued to think about my previous question and I realized I need to split my question into two (related) ones:

(1) what are the PROPORTIONS or MAX AMOUNTS of FAT and PROT that will allow me to BECOME lean?

(2) what are the PROPORTIONS or MAX AMOUNTS of FAT and PROT that will allow me to STAY lean?

I understand this probably are different from person to person (based on gender, age, level and type of activity, etc), but is there a rule-of-thumb kind of guidelines I could start off with?

I already follow a very low carb diet but still not lean as I’d like (still abdomen fat deposits), so I assume my PROPORTIONS and/or AMOUNTS of FAT and PROT are what I need to adjust. Any guidelines to follow?

THANKS!

JLMA,

I can tell you from my experience, after losing weight in ketosis, I also had another 5-10 lbs I wanted to lose. A few strategies that helped me:

1.) 2, 24 hour periods of intermittent fasting per week combined with training in my MAF zone ( see Maffetone Method https://www.philmaffetone.com/whatisthemaffetonemethod.cfm ).

2.) Replacing some of my high dairy or moderate protein meals with “bulletproof” coffee ( strong expresso, 2 tbsp coconut oil and 2 tbsp grass fed butter in a blender ). This stuff is amazing, delicious and satiates for very long periods of time.

3.) Saving most of daily carb intake for right after my high intensity anaerobic workouts.

I was able to lose a significant amount of stubborn abdomen fat with this so far.

Adam

Adam,

Thank you for your input. Help me start implementing your input by letting me know how these three tips rank in burning-stubborn-fat-effectiveness (which one is the best of the three tips? second?).

Once you reach your goal, do you plan on quitting these strategies?

Where do I find good coconut oil?

Thanks again,

Although I don’t have any blood testing gear to measure precisely, I think for me, the combination of replacing some dairy and protein with more fat made the biggest difference. I kind of did these 2 at the same time so I can’t rank one over the other.

I have more recently cut back on the fasting because I started cycling to work. That combined with my lunch time workouts left me pretty obliterated while trying to fast. I’m not saying it’s not possible to adapt to this as Dr. Attia has attested to with long bike rides, but I haven’t worked up to that yet and currently don’t plan to. If I have an easy workout or rest day, I might still fast until dinner.

I used to get my coconut oil from Trader Joe’s until my wife started liking it. She now cooks with all the time, and we started running out quick. So I actually found some at Costco that comes in 3 quart buckets. The brand is Nutiva, and it’s organic as well. -Adam

Adam,

I am new to coconut oil. I have always (only) used extra-virgin olive oil. Would you say these two oils are interchangeable? Would one be a better choice than the other when the recipe calls for raw oil? and when the recipe involves heating the oil up?

(I thought that by entering my email I’d be getting comment updates, but I am not)

I am new to coconut oil also. I understand it’s best used for cooking, since it will not burn at higher temps. like olive oil would. I’ve been using it for baking and stove top cooking, but still use olive oil for salad dressings and sauces (low temp. cooking).

Hi, Peter. Thanks for such detailed information. I have a question — how do you square what you are saying with the assertions of the Calorie Restriction folks and the studies by Dr. Roy Walford (and others) who put the focus on eating a primarily vegetable diet (the only way to their way of thinking that you can get your calories low enough to contribute to life extension). I really can’t reconcile what Walford/ Ornish/ Barnard etc. are saying with what you and Gary have contributed (I talk about my struggle some in my new blog: https://foodchoicecity.blogspot.com/). Lots of folks with good credentials/intentions with wildly differing opinions. Yikes!

Can you help me understand this? The more books I read, the more my head spins. I really don’t know what to eat anymore.

AC, I hear your struggle and you certainly could not be faulted for it. It is something we all live with. I don’t know your background and how familiar with you with scientific methodologies, but a few of my posts may be helpful:

https://eatingacademy.com/books-and-articles/good-science-bad-interpretation

https://eatingacademy.com/nutrition/is-red-meat-killing-us

https://eatingacademy.com/nutrition/how-do-some-cultures-stay-lean-while-still-consuming-high-amounts-of-carbohydrates

Hi Peter, thanks for a great website. I’m new to low carb eating and have one question. Do I still need to eat during workouts? I’m a cyclist and I do rides of about 2-4 hours 3 times per week. I rode for 2 hours the other day and felt fine with just water, but my husband is concerned that I’ll pass out or something. I should mention that I’m trying to lose weight (and at 27% fat I think my body should burn it’s own fat for energy) I read that you take cream and nuts during training, but I don’t train anywhere as much as you. What do you think?

Thanks

Desiree

See posts on interplay of exercise and ketosis. I can’t really know if you need to eat, but hopefully these posts will help you think about it in your case.

Hi Peter,

I came across this BBC documentary https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/7838668.stm (the show can be streamed here https://www.dr.dk/tv/program/hvorfor-er-tynde-mennesker-ikke-fede on a Danish site for free). The idea is that a group of people overeat for one month on crappy food and gain weight. The interesting is then that they, more or less, lose all of it again in one month without any special effort but just by living like they use to. The conclusion is that we all have a genetic weight set point. They only tested weight, body fat and measurements and not how the diet affected blood markers etc. They also do an experiment to show that some people are genetically disposed to eat even though they feel full.

For what it’s worth, I wanted to share the documentary.

Good luck on your current work.

Hemming

Thanks, Hemming. The question I have from this is what accounts for the average rise and individual rise in the majority of people?

Do you mean in terms of it’s the calories or the food choices? Or whether which factor (be it gene, activity level etc.) that affected their weight gain the most? I would also have liked to see the macronutrient breakdown of the diet. What I found particularly interesting is how some people ‘can’t’ overeat. This is also something I’ve noticed with myself in that I find it easier to eat less than more – something that made it very easy for me to lose too much weight and currently really difficult to gain anything.

I agree that there are a lot of open questions to this experiment. I assume BBC just paid for it to make a show and not a scientific study.

I don’t agree with the notion (or, more specifically, the implication) that there has been a genetic shift in our set point to be more obese. Certainly a set point plays a role, but I’m not sure it’s pre-determined. I’m guessing it’s more epigenetic than genetic, when it comes to movement.

good morning doctor i would like to know how to stop diarrhea in a high fat diet.

iam 6foot for 250bl how much fat to i need. iam struggling with those 2question if you can please help thank you

I just discovered your site today, and have spent many hours reading through posts and comments. So much great material!

I would like to ask … what about those of us who do not get into ketosis? In my case, I get fasting (even 12hr+) BG results of, say, 400. Current HbA1c = 11.1%. Have had raging diabetes, not just IR, since age 35 (21 years), and under today’s standards probably would have been warned between the ages of 17-21. Multi-century history of this type of thing on the side of the family I resemble. My diet is carb-limited (no rice, pasta, bread, soda, added sugar, other junkfood) but not truly low-carb at the moment. Reading your site may inspire me to try yet again.

Metabolic complications include iodine hypersensitivity and low body temperature, with reverse fevers. Have failed on all diabetes drugs (severe side effects), and current ~30 units/day of Levemir doesn’t seem to do anything. I’m terrified of increasing the dose and just gaining more weight, staying on the same hamster wheel. I realize you can only make general statements here, but have you seen results absent ketosis?

In short, yes. I understand your concern, though, and I’m glad you’re considering a dietary change.

Dr. Attia, thank you so much for this website. I sent an email through NUSI, but I’ll post here as well.

I am an RD from Costa Rica, I found your site after listening to your TED talk.

First congratulations, and thank you for making the infomation so accesible. As I understood insulin’s role in biochemistry , I questioned the “conventional dietary advice” they were telling me to give. Good thing I have learned not to apply it!

I want to share this blog with my patients, and request permission to share the key concepts you point out in Spanish, all cited obviously. I think it will be of great value, specially this article since a lot patients insist on counting calories!

Thank you !

Thank you, Rebecca. Glad to hear it.

Hi Peter! I’ve been reading this blog since you started it and have deep gratitude for your willingness to share all of this with us free of charge. Generous doesn’t even begin to describe it, and although it’s a “labor of love,” that still means there’s lots of labor involved! So thank you.

Dig this quick bit of housekeeping (and I only bring this up because your pristine writing tells me that you place a high value on this sort of thing): Under “Key Concept #3- Current Dogma,” you write:

“…but the possibility remains that another factor led to you to overeat.” I think there might be an extra “to” in there. Maybe it should read, “…that another factor led to your overeating” or “…that another factor led you to overeat.”

Super trivial, but I hate when I make little typos on my own blog and I love it when people let me know about it.

Again, thanks so much for your work. You have maintained a standard of quality in your writing, your public speeches, and your demeanor in interviews that lends some much-needed legitimacy and professionalism to this movement.

Thanks Jim. I’ll try to remember and fix.

Hi Peter,

first of all awesome website I have to say… Quite interested in the nutrition stuff because all my doctors are still on quite the old dogma to eat about 60% carbs and “JUST” reduce the kcl intake. Which I do about 5 years and nothing is happening… Enough said 😉

I just started about one and a half week ago with Atkins phase 1 and it is working quite well for me right now (lost 5 kg)… What I am still unsure of is, how much kcl I should intake? With “help” of the doctors I just comsumed about 1800kcl per day. So my metabolism might me quite down :/

With 3 different calorie/bmi calculators I came up with ~2200kcl basal metabolism and ~2900kcl total turnover. And I am sticking with about ~2500kcl.

Do I need to adjust this? Cause I am already hitting a plateau :/

What did you consume/count!?!?

Thanks a lot!

Ultimately, it seems that you are saying that what we eat affects our hunger/appetite, and that in turn affects how much we eat. Is this a reasonable summary?

Also, could you clarify a little what you referring to when you write “Conventional Dogma”? Do you mean the scientific consensus, or something else?

Correct. And by conventional wisdom or dogma I mean the adage that fat balance is DETERMINED by the number of calories ingested (rather than, say, the number of calories ingested is determined by something else, such as hormones and enzymes in our body that regulate fuel partitioning).

So as someone not in the field (my field is computer science), it doesn’t seem surprising to me that hunger/appetite is affected by diet composition. In fact, the exact opposite, that diet composition had NO effect on hunger/appetite, would actually seem to be more surprising.

I’m somewhat surprised (or perhaps “dismayed” is the more accurate word) that the science has not been settled on this decades ago. One study that might be interesting would be to simply put one group of people (who were trying to lose weight) on a high-fat diet, the other group on a high-carb diet, and let them eat as they wished. The tricky part would be how to maintain the diet composition without imposing any other restrictions that might bias the results. (Or maybe such a study has been done?)

As an aside, I’ve found your personal site to be quite informative. I’ve recently been trying to go from 145 to 130 lbs., and have been looking for a site that provided in-depth analysis of the science. On a personal note, I’m currently collaborating on a project looking for epistatic effects between the mitochondrial genome and the nuclear genome in yeast. I wouldn’t be surprised if somewhere down the road we discover that epistatic (and epigenetic) interactions between the mitochondrial DNA and the nuclear DNA are in part responsible for obesity.

Kenneth, I hear you. Perhaps my math/engineering background is why I’ve come to the same conclusion over time.

I was thinking about this as an idea, “Is it possible to hack your body to burn fat, while feasting on low carb whole foods”? I decided to take the idea of the bulletproof diet, and the idea of keto that allows me to think of making a combined plan, Not totally paleo(bulletproof diet) because It would still rely on a lower amount of carbs like 20 or less, and include diary fat, and no refeeding. I was thinking about this from one person that told me about a plate, If your plate is 80%+ fat and rest is from protein and few carbs like less then 9grams an hour but as long as your eating a huge amount of fat you will never have the possibility of that food to ever turn to fat on the body. Almost like a soldier defending your body from getting fat. Then I was thinking about how true it is that if your body is eating a lot of food, which some make it seem hard to do. but oddly I find fat not filling so I can eat alot.. Any ways, I mean like enough over 2000 or more that your body will never be in starvation mode and begin to drop those fat pounds cause it wouldn’t have to think about holding on to anything your eating since your never in starvation mode. Your body will be thinking.. I guess I am being fed I’ll always have energy so I can keep working and not hold on to anything new that comes in from the mouth. Then your body will be using all the food and excess from your body as well, while perserving the muscles from the protein intake being enough to keep and maintain them. which will also lead to weight loss.

I was wondering with your thoughts… if you had any thoughts to the idea if your body is running on unlimited amounts of fats, from 75-90% like would they really be able to lose a way lot more easier then eating a typical low carb plan?

I knew of the guy who did the 5000 or so calories a day and was put on youtube

he did a high fat low carb plan for 21 days ended up only gaining only think like barely nothing when he should gained a load of weight… but instead he only gained a few pounds like 3 i think or something and lost inches

which was a surprise then he recently did 5000 and was eating all carbs and junky foods. each day in 21 days he gained 15lbs i think it was and got heavier around the waist

So in some way I was wondering if you might have any idea if its true, that one person to eat a load of fat.. ( no calorie restriction) keeping metabolism high and never running out of energy or thinking about starving. that you won’t ever gain and maybe allow a chance the body to adjust that you begin to lose the weight you need cause your body will be more energized and using all the fat on and what your put in your body, without thinking about saving any… Do you think is this a possible thought?

thank you

I ment to put for a female very much low in the weight department, been testing the idea and ahve been at 2600-3000 calories a day.. and been pretty good .

from 1600-1700 was able to lose 2 lbs in 3 days then moved up to 2000-2200 and soon lost another pound

so now eating 2600-3000 and no weight loss yet but only been well today is day 9 so in a week lost 3 lbs and starting week two.

I just found it hard that i’m oddly hungrier during the day cause i’m eating a lot less food even tho i eat 5 times a day every 3hours. but I notice my appetite is high cause fat don’t really fill me,

so my other question I ment to ask is, Do I keep my protein the same and just add in loads more fat.

a typical meal is like half an avocado,( have usually with every meal) and tblspoon grass fed butter with either if pork loin boneless pastured 4oz size or a fattier amount of meat with grass fed beef 85% lean

doesn’t keep me full for long, but tastes good tho if i could i’d love to have more but wasn’t sure how to approach it. I do want to see if more = will boost weight loss or even cause maintain since at a no need to lose, at a low weight allready.. or if its a bad idea, to go pass the ( old saying 3500 calories= 1lb) when typically its what your eating..

what do you think?

sorry for so much questions.