I recently received a link to a blog post summarizing a 2021 study with such gobstopping results that I must admit my initial reaction was: this seems too good to be true. The title of the study is “PR Lotion significantly improves high-intensity interval performance.” Specifically, the study found more than a 20% improvement in high-intensity interval training to exhaustion in a study of competitive cyclists.

In sports requiring intense endurance lasting between about one to ten minutes, a 1 to 2% improvement can often make the difference between reaching the podium or the middle of the pack. A 20% improvement is staggering.

“Coming on the heels of the clinical trial at San Diego State University [SDSU] by Dr. Mark Kern that showed notable improvements in both performance and recovery from the Topical Edge Performance & Recovery group,” writes a blog post from Amp Human, “Source Endurance performed an independent study of their own.” Topical Edge is the former name of the company that is now Amp Human, which sells PR Lotion. The “PR” apparently stands for performance and recovery (I assumed it stood for ‘personal record’). Let’s unpack this independent study by Source Endurance first and then consider the other clinical trial from SDSU.

The Topical Edge investigators recruited eight volunteer competitive cyclists and put them to the test: each of the participants completed two sessions of high-intensity intervals two days apart. For the first session, half were randomized to PR Lotion and the other half to a control lotion that contained all the ingredients of the PR Lotion except the active ingredient. For the second session, the participants “crossed-over” to the alternate lotion so that each participant performed one session using the PR Lotion and the other session using the control lotion. Neither the investigators nor the participants knew which lotion they received in both instances. In other words, this was a double-blinded, randomized, controlled crossover trial, which is a particularly rigorous study design.

Two days before the first session, all of the participants performed a 20-minute time trial (TT) to set and calibrate the power of the intervals for the ensuing testing sessions. For the testing sessions, the participant was instructed to apply a tablespoon of assigned lotion per leg 30 minutes prior to beginning a warm-up on a smart indoor bike trainer. The warm-up lasted six minutes, and then the participant began the test: a 30-second interval at 140% of their TT power followed by a 20-second rest interval, and the pattern repeated until the participant could complete the work interval.

The study found a significant difference (P = 0.009) between the PR and control lotion in the number of high-intensity intervals completed before exhaustion. Participants completed an average of just under 14 intervals when using the control lotion compared to 17 intervals with PR Lotion, which works out to about a 20% improvement using PR Lotion vs the control lotion. (Nota bene: this study is not published in a peer-reviewed journal.)

Why does it work (if it works)?

So what is this magical lotion? It’s essentially nothing more than a topical delivery of sodium bicarbonate, more commonly referred to as baking soda. As it turns out, athletes have used baking soda for decades – it’s one of the most extensively studied ergogenic aids out there. But why would baking soda of all things improve performance?

A general principle of exercise is that the higher the intensity, the more acidic your muscles and blood become, as hydrogen concentration increases in lockstep with lactate concentration (hence the term “lactic acid”—an acid formed by the the pair). An acidic solution is defined by having a concentration of hydrogen ions (H+) greater than that of pure water. An accumulation of H+ creates an acidic environment and can decrease the contraction capacity and force of the muscle by up to 50%. (It’s this inhibition of contraction/relaxation of the microscopic subunits of muscle that creates the painful sensation during intense exercise, not the accumulation of lactate, per se.) Baking soda has alkaline or base properties, which can neutralize excess H+, giving baking soda the potential to counteract the acidification of blood. If this happens during higher intensity exercise, it might allow someone to work a little harder and/or a little longer before they reach exhaustion.

Studies suggest that baking soda indeed offers a small benefit during hard exercise bouts lasting between about one and ten minutes, although the results are inconsistent. So why doesn’t everyone looking for an edge spike their water bottles with Arm & Hammer before a competition? Because of course, there’s a catch: many people using it experience gastrointestinal side effects which can limit its efficacy. In other words, cramping, vomiting, or diarrhea can more than offset any benefits from baking soda. But delivering the baking soda through the skin bypasses the GI tract and limits these adverse effects. In fact, the 2021 PR Lotion study described above notes that no side effects were reported by participants.

Earlier Evidence

As alluded to, this actually wasn’t the first study testing the benefits of PR Lotion. The 2021 trial references another from 2018, which, according to a blog post from the company’s manufacturers, is awaiting submission for publication. However, results from this trial and two related poster presentations are summarized in the blog post, so let’s look at what they found.

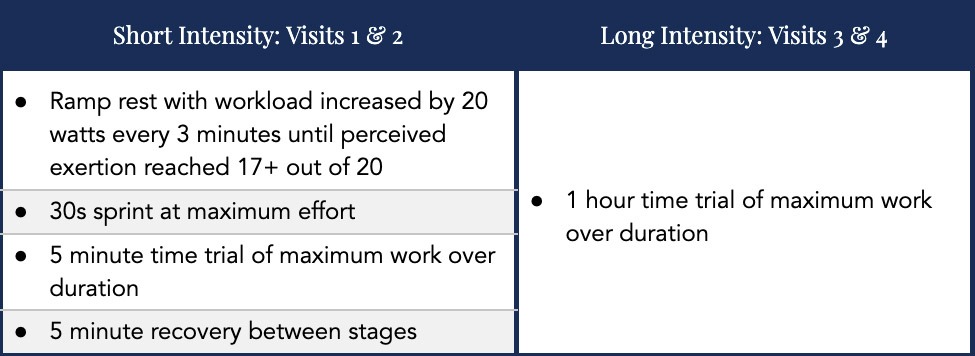

This, too, was a double-blinded, randomized, controlled crossover trial – this time in 20 competitive cyclists. Each of the 20 participants completed two sessions of “short intensity” testing on separate days, and they also completed two sessions of “long intensity” testing on separate days.

The summary results of the white paper indicated PR Lotion was superior to control with statistically significant improvement in reducing delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) following intense exercise, lowering heart rate and perceived exertion (RPE) under the same training loads, and tolerating higher blood lactate levels. (Increased lactate is an indication that the sodium bicarbonate is buffering excess acid and keeping lactic acid in the form of lactate.) However, the investigators did not find significant pH differences. (There’s also another 2020 trial showing PR Lotion was ineffective at altering buffering capacity.) One would expect both lactate and pH to be higher when using PR Lotion if it is in fact more effective at buffering excess acid. When they looked at performance, there wasn’t a statistically significant improvement in either the short or long intensity tests, contrasting the 2021 trial. This wasn’t included in their summary results or conclusion section of the white paper.

What accounts for the lack of performance gain in this study?

One of the limitations to a white paper like this is that it’s a good example of the sharpshooter fallacy. The term refers to the story of a Texan who shoots holes in the side of the barn and then draws targets around the bullet holes. Another way to put it: it’s important to call your shots before you take them. Trials often presented as hypothesis-testing are actually hypothesis-generating because of this bias.

Let’s look at the results again in a little more detail. Poster presentations from the study reveal DOMS was significantly (P=0.007) reduced following the short intensity series, but this was not observed following the 1-hour time trial session. The reductions in heart rate and RPE were significant (P<0.05) for PR Lotion compared to placebo at the 15-minute mark of the 1-hour time trial, but not at any other time points (i.e., at 30, 45, and 60 minutes). Lactate was significantly (P<0.05) higher after the short intensity series, but no difference was observed after the 1-hour time trial. (Recall, this study was not published in a peer-reviewed journal.)

In the short intensity series, blood lactate and pH were measured and compared 14 times. In the long intensity session, HR and RPE were each measured and compared five times. Each one of these time points is an opportunity to find a P value <0.05 or a significant difference between the treatment and placebo. As I’ve written before, when a study reports results of multiple outcomes and multiple exposures, it increases the probability that at least some of those results may be statistically significant even though there is no underlying effect.

How do you avoid this problem? Ideally, the study is designed with a specific prediction or hypothesis in mind, which is then tested through experimentation to determine whether or not the hypothesis is wrong. In this case, the investigators hypothesized that PR Lotion would increase pH and lactate levels and would confer a performance benefit. When they tested this prediction with their experiments, the prediction was wrong. There was no significant difference in performance in either the short or long intensity tests. There was no significant difference in pH in either the short or long intensity tests. There was no significant difference in lactate in the longer intensity test, but lactate was significantly higher (10.8 vs 9.7 mmol/L for PR Lotion and placebo, respectively; P<0.05) after the short intensity series. In a separate poster presentation, the investigators hypothesized that PR Lotion would lower DOMS 24 hours after exercise and would result in faster recovery from DOMS from 24 hours to 48 hours after exercise. Again, the results suggest the prediction was wrong, as 24-hour DOMS scores were not reported and the 48-hour results were split: no significant difference after the long intensity test, but DOMS was significantly lower (P=0.007) with PR Lotion use vs placebo after the short intensity testing.

Regarding the HR and RPE data, these results are hypothesis-generating since they weren’t predicted beforehand and no corrections were made to account for the number of tests conducted. This is also true of the predictions made in the study. Several outcomes at several time points were reported in terms of statistical significance, and the p-value, also known as the α, should be adjusted accordingly, typically using a Bonferroni correction. In other words, you raise the bar on what you deem to be statistically significant to account for the number of shots on goal you get. “If there were only one inference test to perform and only one way to conduct that test, then the P value is diagnostic about its intended likelihood,” wrote Brian Nosek and his colleagues in a 2018 paper on the importance of preregistration and understanding the distinction between postdiction and prediction. “It is not hyperbole to say that this almost never occurs.” (Postdiction involves explanation after the fact, a close cousin of hindsight bias or the I-knew-it-all-along effect. Preregistration is the practice of registering your hypotheses, methods, and methods of analyses of your study before it is conducted.)

Conclusion

Am I convinced of the impressive performance and recovery benefits of PR Lotion related to hard bouts of exercise? Should we dismiss the aforementioned research entirely because of its limitations? I think the answer to both questions is no. The 2021 study is the more compelling of the two studies, both because of its simpler design in terms of a more specific prediction and test and because of its results. In terms of performance, the 2021 and 2018 studies were testing different activities. The 2021 study assessed high-intensity intervals lasting 30 seconds while the 2018 study assessed sustained efforts of five and 60 minutes. The 2021 study was also very small, and the list of interventions that work in very small studies, only to fail in larger studies is awfully long. Nevertheless, one interpretation is that the PR Lotion may be better suited for short periods of intense work coupled with short periods of rest in between. But more than anything else, I believe that looking at these studies more closely is a good opportunity to highlight how challenging it is to produce reliable knowledge even when implementing randomized-controlled trials and the importance of calling your shots before you take them.