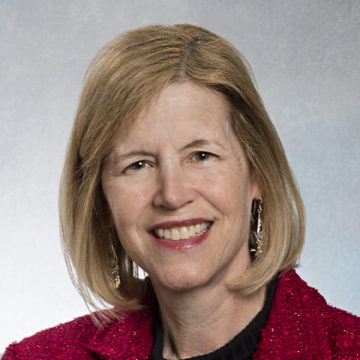

JoAnn Manson is a world-renowned endocrinologist, epidemiologist, and Principal Investigator for the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). In this episode, she dives deep into the WHI to explain the study design, primary outcome, confounding factors, and nuanced benefits and risks of hormone replacement therapy (HRT). JoAnn reflects on how a misinterpretation of the results, combined with sensationalized headlines regarding an elevated risk of breast cancer, led to a significant shift in the perception and utilization of HRT. From there, they take a closer look at the breast cancer data to separate fact from fiction. Additionally, JoAnn gives her take on how one should weigh the risks and benefits of HRT and concludes with a discussion on how physicians can move towards better HRT practices.

Subscribe on: APPLE PODCASTS | RSS | GOOGLE | OVERCAST | STITCHER

We discuss:

- The Women’s Health Initiative: the original goal of the study, hormone formulations used, and potential confounders [4:15];

- Study design of the Women’s Health Initiative, primary outcome, and more [16:00];

- JoAnn’s personal hypothesis about the ability of hormone replacement therapy to reduce heart disease risk prior to the WHI [26:45];

- The relationship between estrogen and breast cancer [30:45];

- Why the WHI study was stopped early, and the dramatic change in the perception and use of HRT due to the alleged increase in breast cancer risk [37:30];

- What Peter finds most troubling about the mainstream view of HRT and a more nuanced look at the benefits and risks of HRT [45:15];

- HRT and bone health [56:00];

- The importance of timing when it comes to HRT, the best use cases, and advice on finding a clinician [59:30];

- A discussion on the potential impact of HRT on mortality and a thought experiment on a long-duration use of HRT [1:03:15];

- Moving toward better HRT practices, and the need for more studies [1:10:00]; and

- More.

The Women’s Health Initiative: the original goal of the study, hormone formulations used, and potential confounders [4:15]

What is the h-index, and how is it calculated?

- The h-index is calculated from the number of publications you have that are highly cited

- If, for example, you have an h-index of 100, that would mean that you have at least 100 publications that have 100 or more citations each

- An h-index of 200 would be 200 publications that each have at least 200 citations that are referenced in other publications

- These are epic h-indexes

- A person with a h-index of 100 has done 10 people’s lifetime work in their lifetime

- Last time Peter checked, JoAnn’s h-index was 305

- She’s in the top 3 h-index rankings in the history of biomedical science

- JoAnn clarifies, “It means I have wonderful colleagues in collaborations going on throughout the world”

The goal of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI)

- JoAnn was one of the principal investigators on the WHI

- Looking back, 20 years later, this study wasn’t interpreted in the best way, from a public health perspective

- This was a randomized experiment designed in the early 1990s to test what was being found in the Nurses Health Study and other epidemiologic studies

- In the 1980s and 1990s there were several large observational studies of women on hormone therapy

- Compared to women not on hormone therapy, they tend to have lower rates of heart disease in those studies compared to women not using hormone therapy, less cognitive decline, lower all-cause mortality

“We often say that observational studies of this nature cannot prove a cause and effect relationship, but they can generate hypotheses to be tested in randomized clinical trials”‒ JoAnn Manson

- Before the randomized clinical trials were launched in the early 1990s, there was already an increasing practice in clinical medicine to prescribe hormone therapy for the express purpose of trying to prevent heart disease, cognitive decline, and other chronic diseases

- This was a trend not only in recently menopausal women, or when women had hot flashes and night sweats and were in early menopause

- Many clinicians were starting to prescribe these hormones for women who were well over a decade, 10, 20, 30 years after the onset of menopause

It was very important to understand whether this practice of prescribing menopausal estrogen therapy or estrogen plus progestin therapy was advisable when used for prevention of chronic diseases

- This was a very different question from, “Does hormone therapy reduce hot flashes, night sweats, and should women in their 40s, early 50s who are just starting to go through menopause take hormone therapy to treat those symptoms?”

- It was accepted that hormone therapy is effective for treating hot flashes and night sweats

- It’s actually FDA approved for that purpose

- It has an indication for treatment to reduce hot flashes and night sweats

- But the question of its use for prevention of heart disease, stroke, cognitive decline, other chronic diseases had never been tested in a randomized clinical trial, and that was the goal of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI)

- Despite the fact that the epidemiology suggested benefits in all of those arenas, people who listen to this podcast are no strangers to the different types of biases that can creep in

- Like the healthy user bias—It could easily be the case that the women who were provided hormones had access to the type of physicians who maybe were more knowledgeable or provided better care

- There was no doubt that an RCT was going to be essential to elucidate the causality here

The history of hormone formulations [11:00]

- The idea of replacing estrogen in menopausal woman began in the 1960s

- The most common formulations were conjugated estrogen with and without medroxyprogesterone acetate

- Women who had a hysterectomy could use estrogen alone, but women with an intact uterus needed to take what we call a progestogen

- Progestogen counteracts the effect of estrogen on increasing the thickness of the uterine lining, the endometrium

- If women who have an intact uterus take estrogen alone, they have a very high risk of developing endometrial cancer

- Early on, they will just have proliferation and of the lining of the uterus and increased of vaginal bleeding related to taking estrogen without the progestogen

- If women who have an intact uterus take estrogen alone, they have a very high risk of developing endometrial cancer

- Those two formulations (conjugated estrogen with and without medroxyprogesterone acetate) were very commonly used, and they had been extensively studied in the observational studies where the results had looked very promising for a lower risk of heart disease and cognitive decline all cause mortality

It was important to test the formulations that had contributed so much to the observational study findings

Potential confounding factors of observational studies

- Women who were taking hormone therapy in the observational studies tended to be a higher socioeconomic status, more highly educated, and more health conscious

- These may have contributed to their lower risk of chronic diseases

- However, it’s also important to note that in observational studies, the women who were being prescribed hormone therapy were still largely women in early menopause

- Hormone therapy was started in early menopause, even if they continued into mid and later menopause

- That’s another important perhaps biological difference between the women in the observational studies and women in randomized trials, in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI)

- The average age of participants in the WHI was 63, or more than a decade past onset of menopause when the hormone therapy was being started

Do we know if the age of menopause is moving over time?

- We know that girls are getting their periods earlier and earlier, even over just two decades

- JoAnn doesn’t know if that has been rigorously studied

- The average age of menopause is 51, and that has stayed relatively constant for quite a while

Why were conjugated equine estrogen and MPA synthetic progestogen the dominant forms of these hormones used in the 80s and in the 90s, which of course then became the precursor for the epidemiology?

Do we know why there was not just a bioidentical estradiol and progesterone?

- One theory is that a pharmaceutical company developed the conjugated estrogens

- Originally, they derived from the pregnant mare’s urine

- This is true even for many of the forms today

- This pharmaceutical company really became the dominant force in terms of hormone therapy

- Synthesis of estradiol from plants is a more complicated process that really did not get going on a large scale until more recent decades

- For quite a long time (more than 50 years), only conjugated estrogen available

Study design of the Women’s Health Initiative, primary outcome, and more [16:00]

How many lead investigators were on the WHI?

- In the overall Women’s Health initiative there were initially 16 clinical centers and then expanded to 40 clinical centers for most of the duration of the WHI

- There were actually 40 Principal Investigators throughout the country

Were women who were having vasomotor symptoms excluded?

{end of show notes preview}

JoAnn Manson, M.D.

JoAnn Manson earned her Bachelor of Arts degree from Harvard. She went on to Case Western Reserve School of Medicine for her MD, then returned to Harvard School of Public Health to earn her MPH and DrPH.

Dr. Manson is an endocrinologist, epidemiologist, and Principal Investigator of several research studies, including the Women’s Health Initiative, the cardiovascular component of the Nurses’ Health Study, the VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL), the COcoa Supplement and Multivitamin Outcomes Study (COSMOS), and others. Her primary research interests include randomized clinical prevention trials of nutritional and lifestyle factors related to heart disease, diabetes, and cancer and the role of endogenous and exogenous estrogens as determinants of chronic disease. Currently, she serves as the Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She is a Professor of Medicine and Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health at Harvard Medical School, and she is a Professor of Epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Dr. Manson has received numerous honors, including the American Heart Association’s (AHA) Population Research Prize, the AHA’s Distinguished Scientist Award, AHA invited lectureships (Ancel Keys and Distinguished Scientist lectures), election to the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (National Academy of Medicine), membership in the Association of American Physicians (AAP), fellowship in AAAS, the Woman in Science Award from the American Medical Women’s Association, the Bernadine Healy Award for Visionary Leadership in Women’s Health, and the Massachusetts Medical Society awards in both Public Health and Women’s Health Research. She served as the 2011-2012 President of the North American Menopause Society.

Dr. Manson has published more than 1,200 articles and is the author or editor of several books and textbooks. She was also one of the physicians featured in the National Library of Medicine’s exhibition, History of American Women Physicians. [Brigham and Women’s Hospital]

That did not go as I expected.

In juxtaposition with the incredible, life-changing episode with Carol Tavris and Avrum Bluming, this episode with JoAnn Manson left me with three major concerns. First, she seems to have the typical stance of “as low a dose as possible, for as little a time as possible” that many proponents of HRT hold. Second, she stresses over and over again the symptoms of hot flashes and night sweats, while virtually ignoring cognitive function and, as Peter points out, bone health and a host of other symptoms that cooccur with menopause. Third, she recommends the North American Menopause Society. But as anyone who has navigated trying to find a menopause specialist will tell you, the society (of which Manson herself is a member) does not differentiate between doctors who advocate for intelligent, longer-term HRT for reasons other than hot flashes and night sweats and those who believe hormone replacement should be done at the lowest dose possible for as little time as possible. This leaves women to navigate and in fact have to vet a sea of doctors who all claim to be HRT-positive but who are, in fact, not. This is a virtual nightmare to anyone trying to obtain intelligent, long-term treatment.

I completely agree with you… Very disappointed…

Agree 100%

This echoes my thoughts as well. As a menopause coach, I often help my clients find a specialist to prescribe and help them navigate HRT treatment. But, even a NAMS specialist advises the outdated “lowest dose for the shortest amount of time” for women who would be candidates for possibly a higher dose for longer. All I can do is educate, but I’m not a doctor so I have to partner with others to get clients what they need. Thanks for sharing!

As a 54 year old mother of 6 I really appreciate this latest podcast with JoAnn Manson. coupled with episode #42 has been a game changer. I was able to articulate what I wanted as a patient for HRT with confidence. JoAnn gave me more assurance in my personal HRT & explaining the RCT’s. I grew up being told that any form of HRT would lead to breast cancer. Feeling fortunate to not be experiencing hot flashes, night sweats, and loss of sleep. I should of had the information a few years earlier, but super happy to have it now.

Very interesting discussion. I enjoyed listening to a podcast offering diverse views on a topic, and clearly this guest knows her data.

I am post-menopausal and on HRT, which I started last year after menopause (late to the game). I wasn’t having horrible symptoms, but so much is better — skin is less dry, hot flashes and night sweats completely gone, sex drive and natural lubrication back to normal (yay!) — I will be hard-pressed to give it up unless there is compelling evidence to do so.

This was an excellent podcast (which is saying a lot, since we love all of these shows). What was distinctive about this one is you and JoAnn Manson are not in complete agreement, but you both handled it respectfully. She must have known she would get a bit of a grilling, so I really appreciate her willingness to participate. Two things:

1) Neither one of you mentioned the sexual benefits of hormone therapy. Talk about quality of life, especially for older people!

2) The point on reduced mortality due to bone fractures when using HRT seems like a good one, but her data did not show it as something showing up in the all-cause mortality. Or it was cancelled out by something else. The WHI also probably didn’t last long enough for this to show up, would be my guess. This would be a good one to follow up on.

With this, and past podcasts, you seem to just note not for women that have high risk for breast cancer. I would like to see you do a deeper dive on what the large population of women that have had breast cancer should do for the effects of menopause. What should a woman do for bone health once she has completed breast cancer treatment? How to stay healthy for longevity while taking an aromatase inhibitor for ten years?

After listening to Avrum Bluming and reading Estrogen matters, this interview left me flat. No mention that ASCVD kills more women annually than all forms of cancer combined and per Avrum, HRT is beneficial to heart disease. Every doctor I’ve been to, except my ObGyn ( who tells me to never go off of HRT due to the benefits beyond menopausal symptoms) tells me to quit stat. They all mention the WHI study which was a really bad study. How many women have died because of their hot take? I appreciate Dr. Attia’s attempt to answer this. More studies needed but I don’t think companies and the medical establishment see the value.

Hi! I really enjoyed this discussion. I am currently trying to wade through the data and find a practitioner that will help me through perimenopause. I am very healthy and have no risk factors. What about the use of progesterone only? This article makes a great argument and I didn’t hear you touch on that. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3987489/

I appreciated this more nuanced look at the WHI study – I think for this who take an interest in this area it is easy to dismiss all the findings of the WHI and take the view that HRT is all good. I agree this wasn’t what I was expecting – and the key take away of concern to me was that data re women who take E and P seems to suggest that there is more risk for older (60plus?) women re BC. Peter pushed back on ACM and bone health but Manson seemed to be saying the jury is out on this cohort. So many confounding factors – including demographic/ age and the out of date hormones. Plus I am guessing that to an extent Manson has to defend the WHI – ie to say that there was some good data that came out of it and they did show some risk re taking HRT. I really don’t want to give up HRT at all – especially since I found out that all the HRT related benefits drop away dramatically when you go off – seems like another large scale trial is unlikely – so how to settle on the right protocol in the meantime ???

Thank you, Dr. Attia, for offering another perspective. However, Dr. Manson only addressed hot flashes and night sweats and did not sufficiently discuss the truly bothersome symptoms of menopause. Since I was urged to stop HRT 8 years ago, I’ve experienced significant bone loss, brain fog, heart palpitations, trouble sleeping, loss of libido, painful sex and weight gain. Almost immediately, I felt old. I want it back for my overall health, quality of life and longevity. Episode 42 with Avrum and Carol was an eye-opener. Estrogen DOES matter and so does living your best life in your 4th quarter.

Peter, I enjoyed this podcast. I agree with you and also with Dr. Manson. As a practicing Gyn in 1999, I agree that the vast majority of IMs, PCPs, Surgeons, Endocrinologists, and too many Og/Gyns read only the summary paragraph and not the entire article. I spend about 6 hours dissecting the specifics. I have always been an advocate for early and as long as necessary use of HRT. I stopped ordering oral estrogen then and also switched to micronized Progesterone. I am also a long standing member of NAMS.

There is still a lack of education regarding this issue.

I was also a member ISCD and was a CCD. I am now retired.

I do appreciate your comments regarding Osteoporosis.

I would suggest as a topic the issue of Breast Cancer Risk Assessment as it has become extremely complicated but very helpful is assessing risk.

Unfortunately, Breast Cancer still controls the conversation regarding HRT.

Neil S. Gladstone, MD, FACOG, CCD