To many people, drug use conjures images of danger and addiction, especially for those of us who grew up with the US “War on Drugs” legislation and the related “Just Say No” campaign. Public dialogue and education wholly discouraged drug use and the abstinence model prevailed. Since then, although approaches for treating substance use and the scientific understanding of addiction have evolved, drug use largely continues to be viewed negatively. The negative biases about drugs and their harms are reinforced by federal drug policy that continues to criminalize drug use, with the exception of alcohol and tobacco. However, drug criminalization does not seem to decrease drug use, addiction, nor drug-related deaths. Look no further than Portugal’s real-world case study that provides insight into the inefficacy of drug criminalization for decreasing drug use and drug-related deaths: In 2001, Portugal decriminalized all illegal drugs—the likes of cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, and MDMA. Overall, the rates of drug use and drug-induced deaths dropped, especially among young people between 15 to 24 years old. Furthermore, decriminalizing drugs along with federally regulating substances may, in fact, save lives. The US saw a record number of overdose deaths in 2020, in part due to a fentanyl-poisoned illicit drug supply. As federal regulation could perhaps abate the contaminated drug phenomenon, along with the case study out of Portugal for drug decriminalization, one might ask why US drug policy remains unchanged, yet.

Enter Carl Hart: a neuroscientist and Columbia University professor, who argues for a different view on drugs in his most recent book, Drug Use for Grown Ups, Chasing Liberty in a Land of Fear. You can find an interview with him that caught my attention here. Generally speaking, I am intrigued by alternative perspectives on any given topic, even if at the surface they strike me as alarming (which this does). In this case, Hart argues that drugs should be decriminalized and regarded as potential tools to seek and sustain happiness. I appreciate how Hart’s work invites us to reexamine the scientific understanding of addiction, which is primarily rooted in the brain disease model of addiction. Below, I will summarize the brain disease model of addiction and its limitations and utility, along with an alternative and more comprehensive biopsychosocial model of addiction.

Hart offers personal anecdotes to assert his thesis for a different view on drug use. For example, he reveals that he uses heroin with his wife, deliberately setting times aside like he would for any other recreational activity. Perhaps in many people’s minds, Hart’s consistent use of heroin would frame him as an addict. However, despite this use, Hart does not meet the requirement for addiction according to the psychiatric Diagnostic Disease Manual, 5th Edition (DSM-V). Addiction is defined in the DSM-V as a range of symptoms that fall within four categories:

- using the substance more often than intended with failed attempts to stop;

- an inability to fulfill responsibilities or socially engage in desired ways;

- risky use, and;

- having physical dependence (including tolerance and withdrawal).

Hart’s account of his drug use doesn’t meet criterion 1, 2, or 3: he uses substance in a way that is in line with his goals and intentions, describes how he engages in his own risk assessment relative to the benefits (setting up a personal framework to reduce risk), and he fulfills his adult responsibilities. Hart notes that physiological dependence, which he has experienced in the past, does not in itself define addiction. He fundamentally opposes the idea that using substance equates to being an addict and having a disease. And in the context of a society that tends to pathologize recreational drug use, the suggestion of positive drug use is striking by contrast.

Whether one agrees with Hart or not (truthfully, if any of my patients came to me and asked what I thought about them using heroin or cocaine in any capacity I would strongly caution them against use, given the risk-benefit profile and assuming there are lower risk alternatives to meet the aims of what they are looking for from the substance), the alternative discussion of positive drug use allows one to think differently about drugs and addiction. These alternative and more nuanced discussions can inform new approaches to therapeutic treatment. One of the most dominant models of addiction is the brain disease model, which identifies neurological factors that lead to use and emphasizes how the brain changes as a result of drug use. Literature on drug addiction as a brain disease characterizes several neuroadaptations, such as: desensitization of the brain’s reward system, functional changes in brain regions associated with decision making and impulse control, and observing conditioned responses to the drug. This model assumes that these brain changes are responsible for the addiction process in someone who uses drugs. However, the possibility of positive drug use in the way Hart describes suggests that these brain changes do not inherently lead to addiction.

The utility of the brain-disease model is that it aims to identify structural and chemical changes that occur in the brain, which in turn drive observable behaviors. But the biological theory does not include other factors that drive addiction. Here is a critique of the brain-disease model that further investigates the supporting data. By itself the theory does not fully explain addiction because it does not lead to comprehensive effective strategies to mitigate or treat drug addiction. The study of other brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s disease allows for pharmaceutical treatment approaches. However, this is not quite the case for addiction. Even though it is treated as a brain disease, successful treatment approaches are often behavioral. Although there are some pharmaceutical interventions for addiction (e.g., methadone, where we trade one addiction for another), the question remains: if addiction was a brain disease, would a behavioral treatment work?

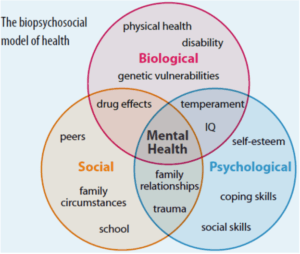

The biopsychosocial model of addiction provides us with another way of looking at disease and attends to some of the limitations of the brain-disease model. The biopsychosocial model, utilized to understand addictive processes, suggests that addiction is not just driven by biology alone but also by psychological and social factors (Figure).

Figure. The biopsychosocial model, depicting the complex interplay of inputs, falling within: social, biological, and psychological areas. Image credit: physiopedia

A person may have a genetic susceptibility for addiction that is revealed within the context of a stressful life experience. A paradigmatic example of a biopsychosocial lens on addiction is the study of North American Vietnam War veterans returning home after service. In the random selection of nearly 14,000 soldiers, 34% were addicted to heroin in Vietnam. But a year after returning home, the percent of those addicted to heroin decreased to 1%. The implication is that addiction, in this case to an opioid, cannot be reduced to a biological phenomenon that forgoes the relevance of the environment that affects psychology. The point is that the nature (genetic) versus nurture (environmental) relationship sets up a false dichotomy. Rather, the utility of the treatment model is that it provides a more comprehensive understanding of the interplay between genetic and environmental factors that result in addiction. Understanding the interplay of factors that lead to addiction can in turn inform a treatment approach that is specific to the individual.

A person’s holistic experience applies as much to drug treatment as it does to the reasons for using drugs. Hart points out that if drugs are thought about in the context of addiction, public regard for their potential positive and pleasurable use tends to be left out. Perhaps it is too reductionist to define utilization as either “good” or “bad.” His argument invites the possibility that drugs can be used to seek pleasure and that this kind of use is distinct from addiction. But the discussion speaks to a larger point: we all look to manage experience in some way. Some people utilize drugs.

While Hart argues that we should view drug use through a more comprehensive lens, he does not necessarily apply the same standard to the complexities of internal experience. In some sense, I am left with the question of what the difference is between seeking pleasure and avoiding pain. Maybe that is what Gabor Maté, who I hope to interview on the podcast, means when he talks about drugs as “emotional anesthetics.” What is clear, however, is that drug use, addiction, and its treatment requires a framework of understanding that leaves room for multiple inputs and perspectives.

After you interview Gabor Mate can you also interview Michael Pollan about his discovery and perspectives since he has written his book ‘How to change your mind’.

Very happy to read your text this morning on addiction. As a therapist specialized in addiction for the last 25 years, its time the US recognized the harm caused by its war on drugs and criminalizing users. Addiction is à public health issue ! Harm reduction and a biospychosocial approach to treatment are evidence-based and used many countries (Canada, Europe)…..I hope your followers will gain a new perspective on addiction, and recreational use of substances. Thanks!

“A paradigmatic example of a biopsychosocial lens on addiction is the study of North American Vietnam War veterans returning home after service. In the random selection of nearly 14,000 soldiers, 34% were addicted to heroin in Vietnam.”

I think you got your numbers mixed up. The reference you provide says that 34% of soldiers had used heroin and 20% were addicted to narcotics (not necessarily heroin).

Great article Peter, and please get Gabor Mate on your show! In my mind he is the leading voice about trauma and its effects on our bodies and lives today.