When I wrote part I of this post, I naively assumed this would only be a two-part series. However, so many great questions and comments emerged from the discussion that I realize it’s worth spending much more time on this important and misunderstood topic. In terms of setting expectations, I suspect this series will require at least four parts.

So, back to the topic at hand…. (You may want to read or maybe reread part I for a biochemistry refresher before diving into part II.)

Is there a “metabolic advantage” to being in ketosis?

Few topics in the nutrition blogosphere generate so much vitriolic rhetoric as this one, and for reasons I can’t understand. I do suspect part of the issue is that folks don’t understand the actual question. I’ve used the term “metabolic advantage” because that’s so often what folks write, but I’m not sure it has a uniform meaning, which may be part of the debate. I think what folks mean when they argue about this topic is fat partitioning, but that’s my guess. To clarify the macro question, I’ve broken the question down into more well-defined chunks.

Does ketosis increase energy expenditure?

I am pretty sure when the average person argues for or against ketosis having a “metabolic advantage” what they are really arguing is whether or not, calorie-for-calorie, a person in ketosis has a higher resting energy expenditure. In other words, does a person in ketosis expend more energy than a person not in ketosis because of the caloric composition of what they consume/ingest?

Let me save you a lot of time and concern by offering you the answer: The question has not been addressed sufficiently in a properly controlled trial and, at best, we can look to lesser controlled trials and clinical observations to a make a best guess. Believe me, I’ve read every one of the studies on both sides of the argument, especially on the ‘no’ side, including this one by Barry Sears from which everyone in the ‘no’ camp likes to quote. This particular study sought to compare a non-ketogenic low carb (NLC) diet to a ketogenic low carb (KLC) diet (yes, saying ‘ketogenic’ and ‘low carb’ is a tautology in this context). Table 3 in this paper tells you all you need to know. Despite the study participants having food provided, the KLC group was not actually in ketosis as evidenced by their B-OHB levels. At 2-weeks (of a 6-week study) they were flirting with ketosis (B-OHB levels were 0.722 mM), but by the end of the study they were at 0.333 mM. While the difference between the two groups along this metric was statistically significant, it was clinically insignificant. That said, both groups did experience an increase in REE: about 86 kcal/day in the NLC group and about 139 kcal/day in the KCL group (this is calculated using the data in Table 3 and Table 2). These changes represented a significant increase from baseline but not from each other. In other words, this study only showed that reducing carbohydrate intake increased TEE but did not settle the ‘dose-response’ question.

This study by Sears et al. is a representative study and underscores the biggest problems with addressing this question:

- Dietary prescription (or adherence), and

- Ability to accurately measure differences in REE (or TEE).

Recall from a previous post, where I discuss the recent JAMA paper by David Ludwig and colleagues, I explain in detail that TEE = REE + TEF + AEE.

Measuring TEE is ideally done using doubly-labeled water or using a metabolic chamber, and the metabolic chamber is by far the more accurate way. A metabolic chamber is a room, typically about 30,000 liters in volume, with very sensitive devices to measure VO2 and VCO2 (oxygen consumed and carbon dioxide produced) to allow for what is known as indirect calorimetry. The reason this method is indirect is that it calculates energy expenditure indirectly from oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production rather than directly via heat production. By comparison, when scientists need to calculate the energy content of food (which they do for such studies), the food is combusted in a bomb calorimeter and heat production is measured. This is referred to as direct calorimetry.

Subjects being evaluated in such studies will typically be housed in a metabolic ward (don’t confuse a metabolic ward with a metabolic chamber; the ward is simply a fancy hospital unit; the chamber is where the measurements are made) under strict supervision and every few days will spend an entire 24 hour period in one such chamber in complete isolation (so no other consumption of oxygen or production of carbon dioxide will interfere with the measurement). This is the ‘gold standard’ for measuring TEE, and shy of doing this it’s very difficult to measure differences within about 300 kcal/day.

Not surprisingly, virtually no studies use metabolic chambers and instead rely on short-term measurement of REE as a proxy. In fact, there are only about 14 metabolic chambers in the United States.

A broader question, which overlays this one, is whether any change in macronutrients impacts TEE.

Despite the limitations we allude to in the summary of this review, there is a growing body of recent literature (for example this study, this study, and this study) that do suggest a thermogenic effect, specifically, of a ketogenic diet, possibly through fibroblast growth factor-21 (FGF21) which increases with B-OHB production by the liver.

These mice studies (of course, what is true in mice isn’t necessarily true in humans, but it’s much easier to measure in mice) show that FGF21 expression in the liver is under the control of the transcription factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor a (PPARa), which is activated during starvation. Increased FGF21 promotes lipolysis in adipose tissue and the release of fatty acids into the circulation. Fatty acids are then taken up by the liver and converted into ketone bodies. FGF21 expression in liver and adipose tissue is increased not only by fasting but also by a high fat diet as well as in genetic obesity which, according to these studies, may indicate that increased FGF21 expression may be protective. Hence, ketosis may increase TEE either by increasing REE (thermogenic) or AEE (the ketogenic mice move more). Of course, this does not say why. Is the ketogenic diet, by maximally reducing insulin levels, maximally increasing lipolysis (which dissipates energy via thermogenic and/or activity ‘sinks’) or is the ketogenic diet via some other mechanism increasing thermogenesis and activity, and the increased lipolysis is simply the result? We don’t actually know yet.

Bottom line: There is sufficient clinical evidence to suggest that carbohydrate restriction may increase TEE in subjects, though there is great variability across studies (likely due the morass of poorly designed and executed studies which dilute the pool of studies coupled with the technical difficulties in measuring such changes) andwithin subjects (look at the energy expenditure charts in this post). The bigger question is if ketosis does so to a greater extent than would be expected/predicted based on just the further reduction in carbohydrate content. In other words, is there something “special” about ketosis that increases TEE beyond the dose effect of carbohydrate removal? That study has not been done properly, yet. However, I have it on very good authority that such a study is in the works, and we should have an answer in a few years (yes, it takes that long to do these studies properly).

Does ketosis offer a physical performance advantage?

Like the previous question this one needs to be defined correctly if we’re going to have any chance at addressing it. Many frameworks exist to define physical performance which center around speed, strength, agility, and endurance. For clarity, let’s consider the following metrics which are easy to define and measure

- Aerobic capacity

- Anaerobic power

- Muscular strength

- Muscular endurance

There are certainly other metrics against which to evaluate physical performance (e.g., flexibility, coordination, speed), but I haven’t seen much debate around these metrics.

To cut to the chase, the answers to these questions are probably as follows:

- Does ketosis enhance aerobic capacity? Likely

- Does ketosis enhance anaerobic power? No

- Does ketosis enhance muscular strength? Unlikely

- Does ketosis enhance muscular endurance? Likely

Why? Like the previous question about energy expenditure, addressing this question requires defining it correctly. The cleanest way to define this question, in my mind, is through the lens of substrate use, oxygen consumption, and mechanical work.

But this is tough to do! In fact, to do so cleanly requires a model where the relationship between these variables is clearly defined. Fortunately, one such model does exist: animal hearts. (Human hearts would work too, but we’re not about to subject humans to these experiments.) Several studies, such as this, this, and this, have described these techniques in all of their glorious complexities. To fully explain the mathematics is beyond the scope of this post, and not really necessary to understand the point. To illustrate this body of literature, I’ll use this article by Yashihiro Kashiwaya et al.

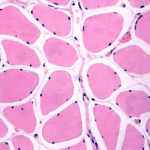

The heart is studied because the work action is (relatively) simple to measure: cardiac output, which is the product of stroke volume (how much blood the heart pumps out per beat) and heart rate (how many times the heart beats per minute). One can also measure oxygen consumption, all intermediate metabolites, and then calculate cardiac efficiency. Efficiency increases as work increases relative to oxygen consumption.

Before we jump into the data, you’ll need to recall two important pieces of physiology to “get” this concept: the acute (vs. chronic) metabolic effect of insulin, and the way ketone bodies enter the Krebs Cycle.

The acute metabolic effects of insulin are as follows:

- Insulin promotes translocation (movement from inside the cell to the cell membrane) of GLUT4 transporters, which facilitate the flux of glucose from the plasma into the inside of the cell.

- Insulin drives the accumulation of glycogen in muscle and liver cells, when there is capacity to do so.

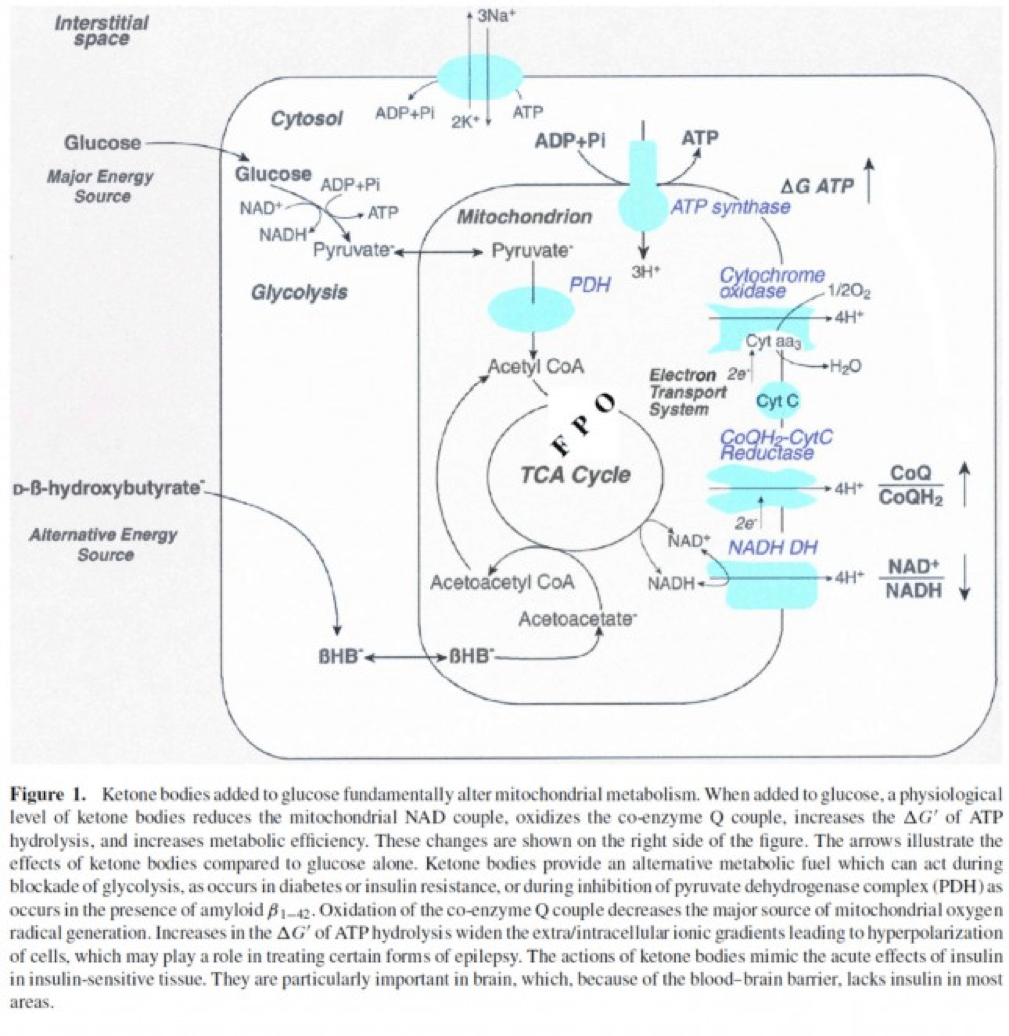

- Least known by most, insulin stimulates the activity of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) inside the mitochondria, thereby increasing the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl CoA (see figure below).

The second important point to recall is that ketone bodies bypass this process (i.e., glucose to pyruvate to acetyl CoA), as B-OHB enters the mitochondria, converts into acetoacetate, and enters the Krebs Cycle directly (between succinyl CoA and succinate, for any biochem wonks out there). I keep alluding to this distinction for a reason that will become clear shortly.

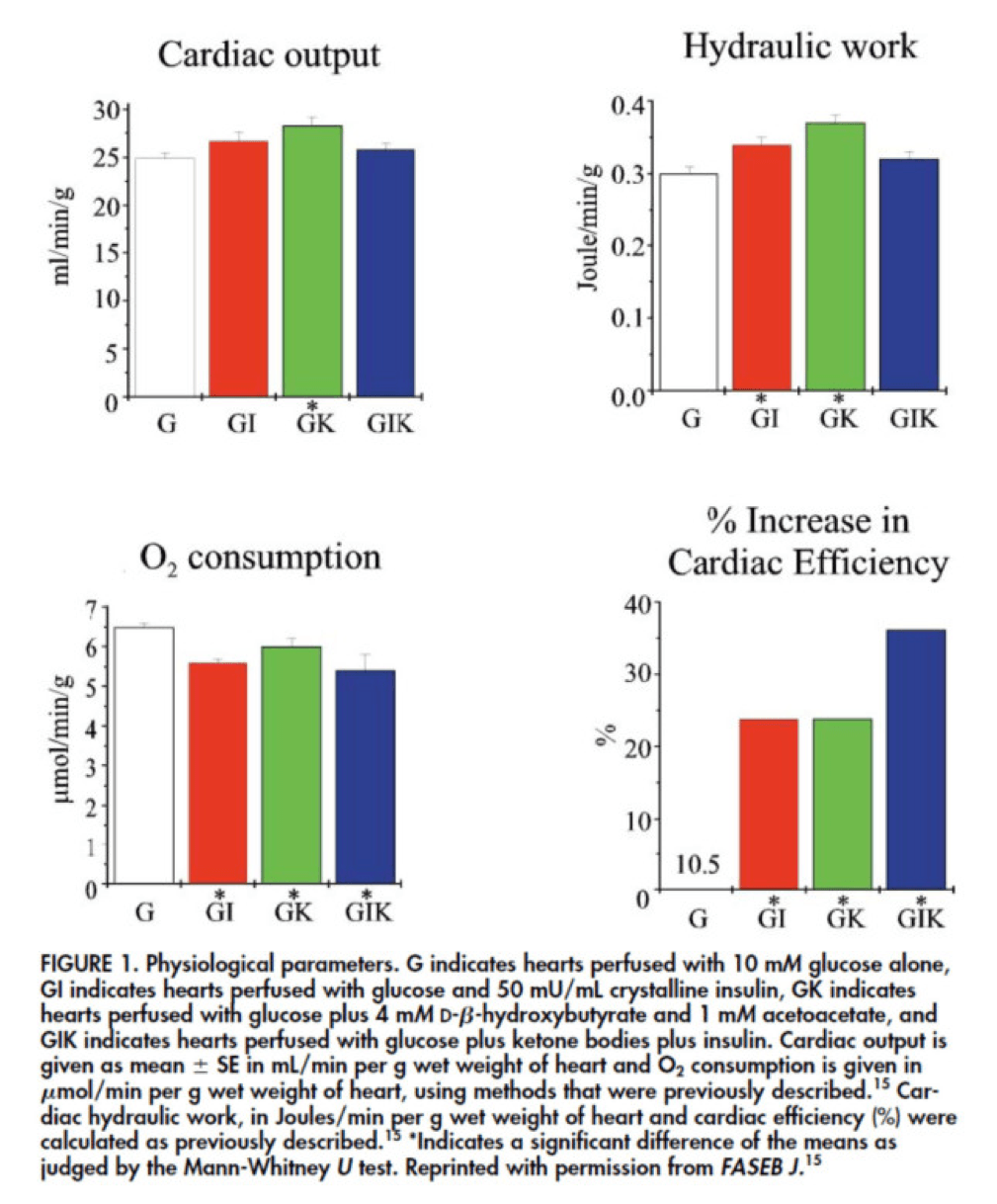

An elegant way to test the relative impact of glucose, insulin, and B-OHB on muscular efficiency is to “treat” a perfused rat heart under the following four conditions:

- Glucose alone (G)

- Glucose + insulin (GI)

- Glucose + B-OHB (GK)

- Glucose + insulin + B-OHB (GIK)

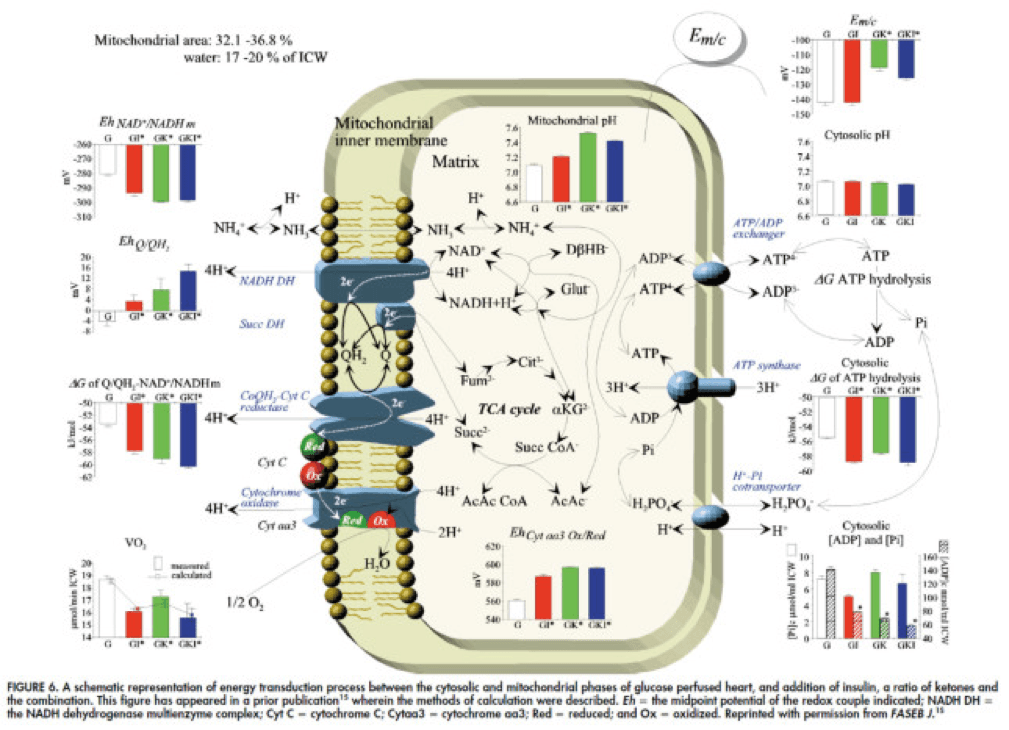

In fact, that’s exactly what this paper did. Look at what they found:

The upper two graphs in this figure show similar information, namely the response of cardiac output and hydraulic work to each treatment. (Cardiac output is pure measurement, as I described above, of volume of blood displaced per unit time. Hydraulic work is a bit more nuanced; it measures the mechanical work being done by the fluid.)

Adding insulin to a fixed glucose (GI) load increases both cardiac output and hydraulic work, but it’s only significant in the case of hydraulic work. Conversely, adding B-OHB to glucose (GK) increases both cardiac output and hydraulic work significantly. Interestingly, combining insulin and B-OHB with glucose (GIK) increases neither.

Oxygen consumption was significantly reduced in all arms relative to glucose alone, so we expect the cardiac efficiency to be much higher in all states. (Why? Because for less oxygen consumption, the hearts were able to deliver greater cardiac output and accomplish greater hydraulic work.)

The figure on the bottom right shows this exactly. If you’re wondering why the gain in efficiency is so great (24-37%), the answer is not evident from this figure. To understand exactly how and why adding high amounts of insulin (50 uU/mL) or B-OHB (4 mM) to glucose (10 mM) could cause such a step-function increase in cardiac efficiency, you need to look specifically at how the concentration of metabolic intermediates (e.g., ATP, ADP, lactate) varied in the rat heart cells.

This is where this post goes from “kind of technical” to “really technical.”

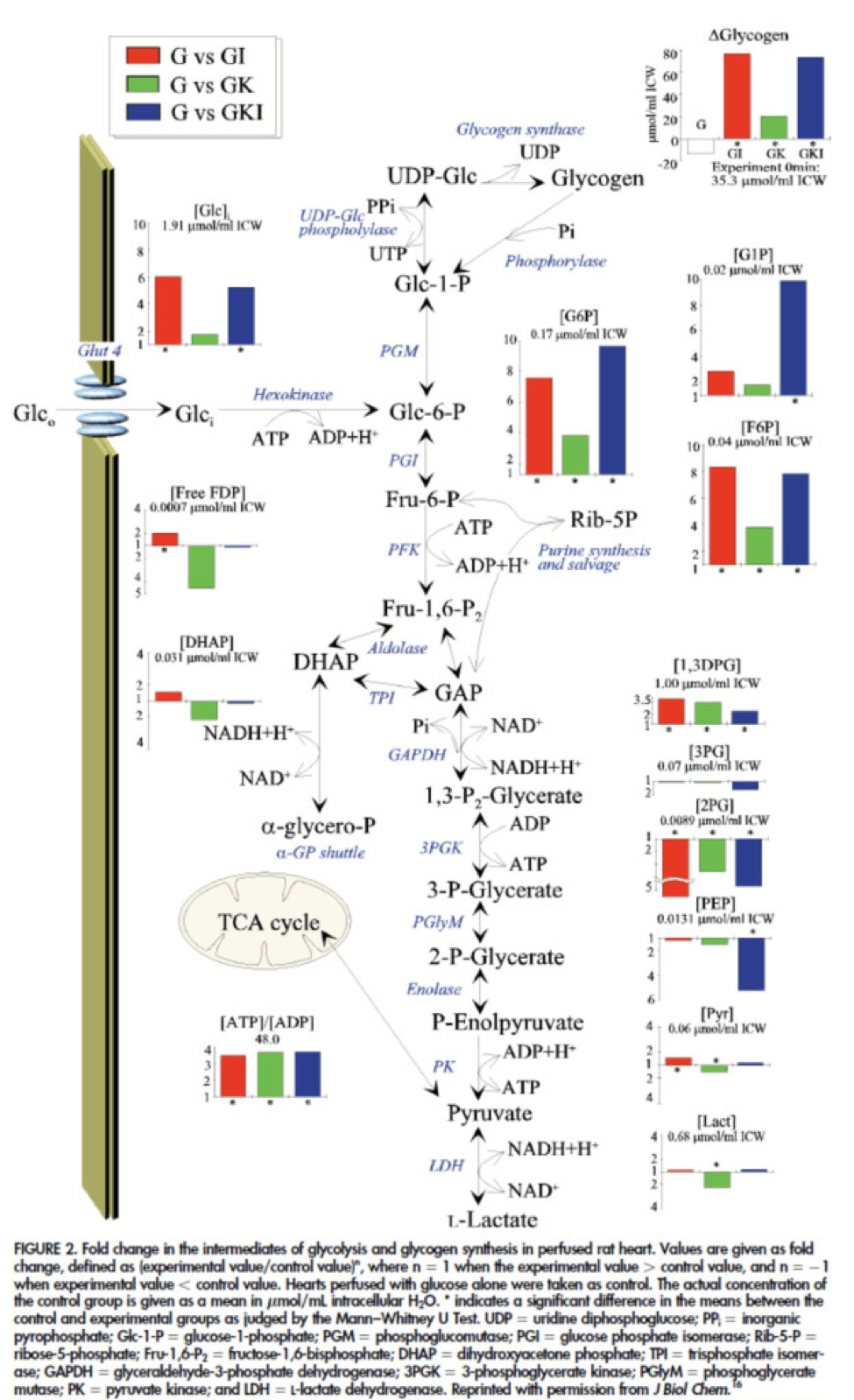

The figure below presents the results from this analysis. The height of the bar shows the fold-increase for each of the three treatments relative to glucose alone. To orient you, let’s look at a few examples. In the upper left of the figure you’ll note that GI and GIK both significantly increase glucose concentration in the cell, while GK does not. Why? The GI and GIK treatments both increase the number of GLUT4 transporters translocated to the cell surface so more glucose can flux in. GK does increase glucose concentration, but not significantly (in the statistical sense).

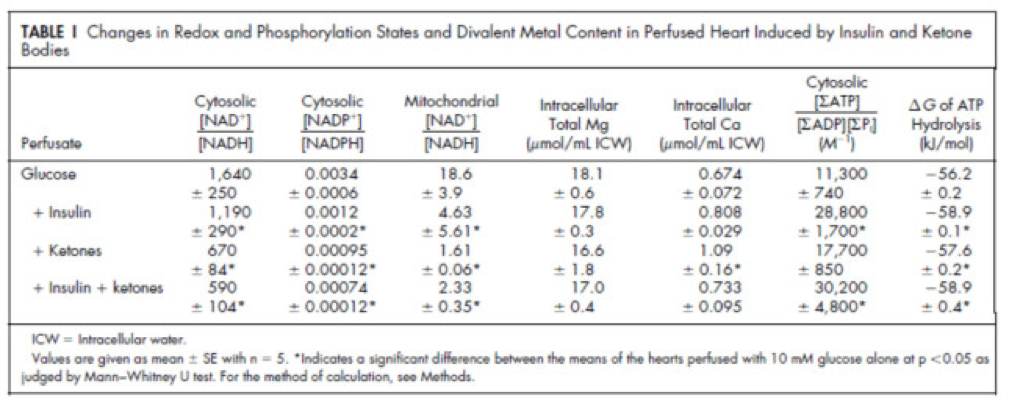

Table 1 from this paper, below, summarizes the important changes from this analysis. In particular, look at the last column, the Delta G of ATP hydrolysis.

I was really hoping to write this post without ever having to explain Delta G, but alas, I’ve decided to do it for two reasons:

- To really “get” this concept, we can’t avoid it, and;

- The readers of this blog are smart enough to handle this concept.

Delta G, or Gibbs free energy, is the “free” (though a better term is probably “available” or “potential”) energy of a system.

Delta G = Delta H – Temperature * Delta S, where H is enthalpy and S is entropy. The more negative Delta G is, the more available (or potential or “free”) energy exists in the system (e.g., a Delta G of -1000 kcal/mol has more available energy than one of -500 kcal/mol). To help with the point I really want to make I refer to you this video which does a good job explaining Gibbs free energy in the context of a biologic system. Take a moment to watch this video, if you’re not already intimately familiar with this concept.

Now that you understand Delta G, you will appreciate the significance of the table above. The Gibbs free energy of the GI, GK, and GIK states are all more negative than that of just glucose. In other words, these interventions offer more potential energy (with less oxygen consumption, don’t forget, which is the really amazing part).

To see what the substrate-by-substrate changes look like across the mitochondria and ETC, look at this figure:

Though it is by no means remotely obvious, what is happening above boils down to two major shifts in substrate utilization:

- In one step the reactants NADH/NAD+ become more reduced (in the chemical sense), and;

- In another step the reactants CoQ/CoQH2 become more oxidized (in the chemical sense).

These changes, taken together, widen the energetic gap between the states and, in turn, translates to a higher (i.e., more negative) Delta G which translates to greater ATP production per unit of carbon.

Additional work, which you’ll be delighted to know I will not detail here, in fact shows that on a per carbon basis, B-OHB generates more ATP per 2-carbon moiety than glucose or pyruvate. As an aside, this phenomenon was first described in 1945 by the late Henry Lardy, who observed that sperm motility increased in the presence of B-OHB (relative to glucose) while oxygen consumption decreased!

Is there a reason to prefer GK over GI?

Yes. Recall that ketones make their way onto the metabolic playing field without going through PDH. Adding more insulin to the equation forces more pyruvate towards PDH into acetyl CoA. While B-OHB “mimics” the effect of additional insulin, it does so in a much cleaner fashion without the complex cascade of events brought on by additional insulin (e.g., decreased lipolysis) and, perhaps most importantly, avoids the logjam of impaired PDH due to insulin resistance (I’ll come back to this point in a future post when I address Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease). In essence, B-OHB “hijacks” the Krebs Cycle via a slick trick that lets it bypass the bottleneck, PDH. All the glucose and insulin in the world can’t overcome this bottleneck. It’s truly a privileged state and a remarkable evolutionary trick that we can utilize B-OHB.

Back to the original question…

Clearly, in the highly controlled setting of a perfused rat heart, ketones offer an enormous thermodynamic advantage (28%!). But what about in aggregate human performance? There is no reason to believe that therapeutic levels of B-OHB (either through nutritional ketosis or by ingesting ketone esters) would increase anaerobic power, since the anaerobic system does not leverage the Delta G improvement I’ve outlined here. Same is true for muscular strength. However, there is reason to believe that aerobic capacity and muscular endurance could be improved with sufficient B-OHB present to compliment glucose.

It turns out this has been demonstrated repeatedly in subjects ingesting ketone esters, developed by Dr. Richard Veech (NIH) and Dr. Kieran Clarke (Oxford). Because the results of their work have not yet been published, I can’t comment much or share the data I have, which they shared with me. I can say the ingestion of B-OHB in the D-isoform (the physiologic isoform), resulting in serum levels between 4 and 6 mM, did lead to significant increases in aerobic power and efficiency in several groups of elite athletes (e.g., Olympians) across multiple physical tasks maximally stressing the aerobic system.

Once published, I believe these studies will be a real shot across the bow of how we view athletic performance. It is very important to point out, however, that these studies don’t exactly address the most relevant question, which has to do with nutritional ketosis. In other words, ingesting ketone esters to a level of 4 to 6 mM might not be the same as de novo producing B-OHB to those levels. But, such trials should be forthcoming in the next few years. Personally, I am most eager to see the results of a ketone ester alone versus nutritional ketosis versus combination treatment, all to the same serum level of B-OHB.

The Hall Paradox

For the really astute readers, you may be saying, “Waaaaaaaait a minute, Peter…if ketones increase Gibbs free energy while reducing oxygen consumption, should this imply TEE goes down?” You’re right to ask this question. It was the first question I asked when I fully digested this material. If each molecule of B-OHB gives your muscles more ATP for less oxygen, you should expend less not more energy at the same caloric intake, right?

I was discussing this with Kevin Hall at NIH, an expert in metabolism and endocrinology. Kevin pointed out the error in my logic. I failed (in my question) to account for the energetic cost of making the ketones out of fat. Remember, in the experiments described above, the B-OHB is being provided for “free.” But physiologically (i.e., in nutritional ketosis or even starvation), we have to make the B-OHB out of fat. The net energy cost of doing this is actually great. According to Kevin, it is not generally appreciated how making ketones from fatty acids affects overall energy efficiency. Nevertheless, this can be examined by comparing the enthalpy of combustion of 4.5 moles of B-OHB, which is about -2,192 kcal, with the enthalpy of combustion of 1 mole of stearic acid (about -2,710 kcal) that was used to produce the 4.5 moles of ketones. Thus, there is about 20% energy loss in this process. Hence, the energy gain provided by the ketones is actually less than the energy cost of making them, at least in theory.

This suggests that being in nutritional ketosis may require more overall system energy, while still increasing work potential. In other words, a person in nutritional ketosis may increase their overall energy expenditure, while at the same time increasing their muscular efficiency. In honor of Kevin, I refer to this as the Hall Paradox.

Parting shot

Ok, if you’re still reading this, give yourself a pat on the back. This was a bit of chemistry tour de force. Why did I do it? Well, frankly, I’m tired of reading so much nonsense on this topic. Everybody with a WordPress account (and countless people without) feels entitled to spew their opinions about ketosis without even the slightest clue of what they are talking about. As I said in part I of this series, there is no bumper sticker way to address this question, so to say ketosis is “good” or “bad” without getting into the details is as useful as a warm bucket of hamster vomit (unless you’re Daniel Tosh, in which case I bet you can find a great use for it).

Next time, I’ll try to back it out of the weeds and get to more clinically interesting stuff. But we had to do this and we’re better for it.

Chemistry by Marcin Wichary is licensed under CC by 2.0

Peter,

I found some disturbing info on the dangers of alcohol and ketosis here- https://sun025.sun.ac.za/portal/page/portal/Health_Sciences/English/Departments/Biomedical_Sciences/MEDICAL_PHYSIOLOGY/Essays/Post-exercise+ketosis

Is there any reason this would not apply to people in NK?

I find many references to people becoming a “cheap drunk” while in ketosis. I have also heard others talk about passing out or blacking out after 2-3 drinks. Would this explain the phenomenon? I think more people need to be warned about this. I had to stop drinking after a black out episode that scared me enough to look into the “cheap drunk” biological mechanism.

I have heard this also, anecdotally, but I’m not sure this explanation is correct. Regardless of the extent of NK, there is always more than enough glucose to meet about half the needs of brain and other cells like RBC. So this theoretical issue he points out is not a real one. The issue of being more impacted by ethanol while in NK is interesting. If the issue is driven by EtOH inhibiting gluconeogenesis, I would expect symptoms of hypoglycemia, which are noticeably different than inebriation.

Are hypoglycemic symptoms themselves counteracted by alcohol? I’m no biochemist but it seems energy deprivation symptoms would be masked, leaving only the inebriation-like effect of hypoglycemia.

Thanks,

The only other explanation I can find is the the metabolic pathways of ethanol and acetone share the the ADH enzyme and the production of that enzyme has been upregulated in NK so one is able to digest the alcohol faster to its toxic metabolite, acetaldehyde.

My 300 lb, LC neighbor had 2 rum and diet drinks and had to be helped from the front porch to the bedroom. Two drinks in a person this size shouldn’t have that effect. After my experience, I have to think it is because of our ketogenic diets. Any other ideas??

Keep me posted with what you find out.

Hello Peter,

Thank you to you for sharing your story and educating those who care to learn. I saw a post above where you mentioned that there are those on the diet whose bodies react differently to dairy and to alternative sweeteners such as Stevia. I have been on the LCHF diet for about 3 weeks and can’t say that I have lost weight – and I too am experiencing exhaustion. I can and will tough it out for the greater good – but was wondering if maybe I too am eating too much protein… a symptom of the Zone diet which I lived for about 20 years – or if the dairy is the culprit. I really just want to be leaner. I have also noticed a few people who mention VLC? Is there a suggested phase of lower calorie? I am thinking that I will cut out whole raw yogurt and stevia as these maybe inhibiting my lean-ness. Any insight would be greatly appreciated. Tips on fighting the exhaustion would be awesome too!!

Thank you again for sharing you story and for this forum!

Blessings,

Holly

Could be, Holly. See the book by Phinney & Volek (the art & science…). Very good reference.

Thanks Peter – will do!!

Dear Dr. Attlia,

I am very impressed by your web site and all the information contained here. Thank you for investing so much of your time and passion into this. I was wondering about ketosis vs. fatty acid oxidation in the muscles. Is there a reason that the liver produces ketones to support muscle function when mitochondria in the muscles can oxidize fatty acids as well? Is ketone oxidation somehow more efficient?

Thank you again for all of this excellent information.

I don’t *think* that’s it, Rob, but I could be wrong. FA and glucose enter the mito via different routes, and I suspect the ketoadaptation process is more about an alternative to the glucose pathway.

Perhaps I missed this in one of the comments, but I just had an interesting change after going on a ketogenic diet. I was mainly interested from the stand point of sports performance. I am a 66 year old male, who likes to cycle long distance. I bought a test device and after lowering my carb intake to between 20-40g per day I measured my beta hydroxy butyric acid, and it would vary from .3mmolar to 3.3 mmolar depending on time of day, and what I did. The very high value was after riding 60 miles.

Here is a before and after snapshot of my lipid profile. Pre-ketogenic diet at about 100g of carb per day these are the lipid values, LDL-P 1300, LDL-C 129, HDL-C 103, Triglycerides 48. LDL size 21.2, LP-IR score 7

After three months on the keto diet at about 20-40g of carb per day the lipid values are LDL-P 1471, LDL-C 162, HDL-C 95, Triglycerides 44. LDL size 21.3, LP-IR score 3.

The LDL-C spiked and I did not expect that. Here is one possible explanation, https://www.lecturepad.org/index.php/lipidaholicsanaonymous/1140-lipidaholics-anonymous-case-291-can-losing-weight-worsen-lipids

One thing that is interesting to me here is that you cannot explain the percentage change in mass concentration of LDL with the change in particle concentration and particle size. Something else is going on (particle composition?).

What is your experience? I certainly felt a lot better cycling on the keto diet. The synthetic starch worked great. My A1c has always been 5.4. Before buying the test meter I did not realize that fasting blood sugar depended on the time of day. Mine starts off in the low to mid 70’s in the early morning and peaks out in the mid 90’s about mid morning (this is with no food consumption). I don’t know what this is good for unless you show up with a fasting blood sugar at 50 or 150.

I did not stumble across this lipid change in Volek and Phinney. Any thoughts would be appreciated.

The difference in LDL-P is within the range of testing variance (easily +/- 10%). The difference in LDL-C is not of clinical consequence, though suggests on average your particle size may be larger (not reflected in the size number they calculate).

Dr. Attia,

Thank you for your sincere desire and commitment to research and understand this issue and work to promote solutions which save lives and promotes good health. Keep searching for the answers and striving to make things better. The problem seems to be getting worse daily.

I was inspired to find you because of your TED Talk. I read this entire two-part post, so I’ll forgive your length of content if you’ll forgive mine. =)

First, I have to say I was disappointed a bit. From your TED talk, it seemed you were newly embarking on a quest to find and help solve the obesity problem. Seemed like you were searching for answers and would remain open-minded.

Yet, reading this post and others, it seems you have already found many of the answers and are willing to readily dismiss others in the field who also have been sincerely searching for answers for decades. It also seems like posts like this are geared toward “fine-tuner” dieters and performance athletes. Rather than those like the obese woman you mentioned in your TED Talk. I appreciate that there are MANY conflicting studies, lots of technical details and subtle nuances to every issue. At the same time, was hoping to see a layperson summary on your site of the common prevailing wisdom, what you have found good/bad about what’s out there and simply concrete steps that everyone can take. Instead, seems like a conclusion has been reached “ketogenic high protein is the way to go” (my take on your approach) and anything that might go against that has flaws. Already, it seems you have taken an unmovable path? Hoping not and perhaps I’m misunderstanding?

If not, perhaps you can invite someone like Dr. Barry Sears (whose study and work you seem to dismiss in this post) to have a debate or to guest post on this issue? If you are truly open to other views, wouldn’t you want your readers to benefit from hearing the other side of the issue? It seems many of your readers quote him — though also seems we are disparaged a bit as being in a “no camp”, so we’d all benefit from inviting him to participate.

As a layperson and not a doctor or trained medical expert, I have been following these issues for 16+ years. I sell no products or services and have nothing to gain, other than improving my health of myself and my family.

But in looking at this, I have found Dr. Sears’ work (decades long), to so far be the most accurate and reliable. He is certainly not part of the “high carb establishment”, but he’s also not part of the “high-protein” establishment either. His point seems to be, “If you can get the same of the benefits from a (barely) non-ketogenic diet, especially related to long-term health, why risk any short or long-term risks that may be associated with (highly) ketogenic diets”? I’m paraphrasing, and don’t want to speak for him, but that’s my take on it. I have come to respect Dr. Sears and not as willing to dismiss his work and theories, many of which probably align with yours, esp. related to keeping insulin levels in a “zone.” His work related to insulin and other hormonal impacts seems solid.

You show studies and data related to short-term “performance” benefits (weight loss, physical performance), but are there studies that also show long-term effects of ketosis? Such as bone/muscle loss in women and the elderly (which seems a potential risk, does it not)? Hunter/gatherers and human evolution didn’t have to worry about breaking a hip at 80 or living healthy at 90 years, evolution just needed to get them to 30-35 years old–avoiding starvation, but also providing them skills to hunt, gather, fight rival tribes, raise their young, social skills, etc. They could probably have eaten anything with enough nutrients to live to 30. So not really the evolutionary “cause and effect” you said you’d look to find in the TED video. It’s just what and the way they happened to eat to survive. Seems as though dietary content/mix is not what made them survive? A ketogenic person could have been eaten by a bear as a non-ketogenic person.

The question which I do not see addressed in this post (maybe I’m missing it?) is: “What do studies show about the long-term impacts (positive of negative) of a ketogenic diet? Esp. looking at bone density in the elderly and/or women?” If you have studies, would love to read them!

Again, I do appreciate your work and am much closer to your view than the “high-carb camp.” But still skeptical of the “high-protein camp” as well.

Thank you for reading/listening.

BC, you are misunderstanding. Do not confuse this silly little personal blog with my job. For a description of what I do “for a living” please see our website at nusi.org. Don’t worry, you’re not the first person to confuse my hobby with my job. I hope I can continue to blog for fun, but I do worry I will need to shut my blog down if such confusion persists. By the way, I do worry that you may be projecting something in your question. At no point in either of these posts on ketosis do I suggest everyone should be on a ketogenic diet, so I’m a bit confused by the nature of your questions which seems to suggest I have.

Yikes. Dr., I thought my questions were reasonable, based on my understanding of the ketosis issue. But forgive me if I offended you or didnt ask them in the right way. Im just a lay person searching for answers. If anyone else reading this, particularly anyone else familiar with concerns around ketosis and bone/muscle loss and the work of Dr Sears, perhaps you can translate for me or do a better job of asking the questions. Many of the comments and replies seem to be conversations related to optimizing performance via ketosis, so yes, I guess I am confused about your current thinking on the issue. But I see a few comments like mine, dismissed by saying you are not suggesting that “everyone” should be on a ketogenic diet. Should anyone? Is there evidence of long term benefits and/or risks of ketogenic states or not? Is it an “advantaged state”? Do you see merits in Dr Sears’ work or not? Seem like fair questions and dont seem to warrant threats to shut down the blog.

BC, perhaps another reader an elucidate for you the nature of your first question, and why such comments don’t sit well with me.

To your question, should anyone be on a KD, the answer is yes. BTW – the “famous” Barry Sears paper that looked at KD did not have subjects in ketosis, despite claiming so. But you’ll need to read the paper in detail to appreciate this.

Lastly, I have no idea why you’re confusing — utterly confusing — what I do for a living at NuSI with this silly personal blog. Why do these 2 states need to overlap completely? If I wrote a blog about cars or bikes, would that create as much dissonance?

which comment doesnt sit well? having someone say that content related to a serious health issue like obesity is a “silly little blog”, esp after your TED Talk, doesnt sit well with me. If you did a serious TED talk giving the impression your mission was to find the worlds best bike, regardless of your “day job” of searching for the worlds best bike, yes people might think your personal bike blog with lots of serious, in depth bike gear discussions was not “silly”. Perhaps its legal concerns driving the downplay of the blog on one hand, while getting serious with your own volumes of content and people who seem to agree with your conclusions on the other? why would the job of finding the truth about nutrition stop at work and not be in everything you do, including your personal blog about nutrition, where it seems you are already expressing conclusions from work in your day job?

Have you contacted Dr Sears to hear his side? or only those who seem to agree with the conclusions you have already come to?

I see you still avoided answering the question about any studies showing long term risks or impacts of KD -positive or negative-esp for women and elderly. that is my ultimate question for which I still see no answers.

BC, I don’t think we’re going to resolve this inability to see eye-to-eye. I guess it seems you have a choice: you can stop reading my personal blog, where I write about whatever I want, whenever I want; or you can be patient and wait until I address your concerns, which will happen in time. Please refrain from further comments on this particular thread, as I will no longer address them. Hope you can find something else on this blog that interests you.

BC – Firstly I wanted to put a quick answer to your comments above, I think you have misinterpreted most of the information that Peter has provided via this blog. This, to me, is a personal journey taken by Peter as he investigates how this diet/lifestyle impacts on HIM. Now, what you take from that is up to you.

Peter is a doctor, correct. So am I. I rarely use my title and I avoid using it with regards to this topic as I do not want to display that I am using it to influence others. Many people trust me (rightly or wrongly) because of my title, but I always try to project the fact that all it gives me is a slightly-better-than-lay knowledge of the human body.

I can also appraise evidence better than most.

I have found Peters blog fascinating as I have taken this journey myself, as I believed that it would enhance my health and athletic performance. In my mind it has done both. But what works for me may not work for others.

Ok, now that is done I have some info for you Peter.

I have noted a few things I thought you might like to know.

You remember my comment about the VLF component of HRV being high in the morning, possibly related to RAS? Well, I did some testing, 30 mins after a cup of bouillon the VLF drops significantly. Possibly point proved?

Secondly, I have been testing ALOT with blood ketones, particularly around training and carb intake. I was very very low carb for a long time (and have been low carb for 3 years now) and have been re-introducing carbs into my diet to test the effect. What I am finding is that I can consume very large amounts of carbs around training and stay in ketosis quite happily. I can also have huge huge carb binges (after a half ironman last week, nearly 800g of carbs consumed) and be in ketosis the next day.

I believe this is the level of adaption my body has reached, meaning I slip back into ketosis very easily.

The only thing that ‘knocks’ me out of ketosis is gluttony, whether its carbs, proteins or fats. But I am generally straight back in within a day at most.

I thought you might find these comments useful, as it may help some of your readers appreciate that you maybe don’t need to be too ‘strict’ on yourself when you have achieved adaptation.

Thanks again for your blog, it provides insight into these topics from a (hope you don’t mind me saying) analytical mind.

Tom

Thanks, Tom. You’ll have to refresh my memory on the VLF discussion. Excess protein and CHO will definitely knock one out of ketosis. Excess fat should not, but keep in mind, getting “excess” fast without protein or CHO is very tough.

Hi Peter,

I think its mentioned above. But in brief, I do my HRV daily, to check LF and HF components to aid recovery/training load. I noticed a trend since I started ketosis of a chronically high VLF component. The literature is still unsure what this component means, but possible explanations are the RAS, or thermogenic energy expenditure, as it seemed to correlate with methods to increase this in obese subjects.

Both of these could be increased in Ketosis, due to the salt de-regulation and the thermogenic effect of the ketones.

Anyway, I postulated that it was the RAS as it was first thing in the morning, prior to my bouillon.

I did some testing, and true enough 30 mins post bouillon the VLF went from 80-90% of the power to ~60% which is what I would normally expect.

On the second half of my comments, what I meant was that from my testing it does not seem to be about what you take in, in terms of carbs, proteins, fats, its when you take them in in regards to what your body wants and when.

For instance today I did a 5 hour ride.

The first 2 hours were water only, the 3rd hour was BCAA only, the 4th and 5th hour was Vitargo, a complex starch. I would use superstarch but I can’t get it over here in the UK (well I can, but its from spain and is incredibly expensive).

Then, after the ride a massive bowl of gluten free porridge oats and coconut milk.

Ketones before the ride 1.0, glucose 4.0.

straight after the ride 3.0, glucose 6.1

2 hours later, ketones 3.5, glucose 4.5

So, the massive carb intake has not impacted ketosis because my body needed it.

Conversely, I have very large, very fatty (~30g protein, very little carb) meals later on in the evening (when my body doesn’t need it) and my ketones have been 0.3 the next day.

Hence my point about it being gluttony, at the time when your body doesn’t need calorie loads that knock you out of ketosis. I guess that would fit with the idea that ketosis is part of the ‘starvation state’

I completely agree with this, Tom. In fact, if you look at my 24-hour tracings of glucose and B-OHB in the presentation I gave here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NqwvcrA7oe8 you’ll note the same thing. Replacing lost glycogen post-ride does not inhibit ketosis at all. This is why on some days I need to eat 100 gm of CHO, while other days only 30 gm.

hi Peter

thank you for all your efforts to help us understand in a scientific way.

Three months ago I decided to try NK. This for a palette of reasons. I did not have any overweight problem, nor I had bad blood parameters, but this had a price to pay: never stop surveying what I eat and accept the idea that I had to stop eating before feeling satiated. Honestly, I cannot say that I felt full of energy. Furthermore, this way of keeping things in check requires efforts and generates stress; since we can tolerate a finite amount of both it seemed to me a pity to waste them in that way. I also liked the idea of not suffering cravings if I had to skip a meal (it actually happens in my working environment), the perspective of not bonking when running, cycling or mountaneering … you know all this. In the end, with few exceptions, I have never loved that much the carb-based foods and I wanted at least once to allow my taste to guide me.

I must admit that all the advantages I have read in your posts and the associated comments are all there, so no reason to list them again; in a few words I have more energy and clarity of mind. I marginally lost weight, let’s say that I have shaved 1kg, now at 66. Overall, I feel much better. I only had two drawbacks, which turned into two questions I do not know how to answer.

The first is that I feel much more affected by alcohol than before. Before going into NK I could drink a few glasses of wine and feel OK. Now, one glass is enough to make my head float. In absolute terms I guess there is nothing bad with this, provided I reduce the amount of wine w.r.t. before NK, but it is a bit unpractical since I am following a professional sommelier course. Silly, but … real, at least for the moment, so I have to decide if I better stop NK until the end of the course. So the question: is there anything specific in the interplay of alcohol and ketosis? I have read posts in several blogs but none of them looked scientifically solid. I have also seen comments on this same page, from which I conclude that it is a matter of debate. Correct?

The second might develop into a problem, but for now is a curiosity. I decided to have a standard cholesterol blood test. I know that one should check more detailed parameters, but the standard thing is a fast and cheap cross-check with the same measurement I had done a few months before starting NK. I have been scared by the results, although I may simply have biased the measurement myself. I had a fairly normal dinner (moderate meat, cheese, salad with olive oil) the night before – admittedly with a couple of glasses of dry red wine. I hardly believe it could influence the test, though. No breakfast, of course. The morning of the test I woke up in auto-pilot mode and without thinking I laced up the running shoes and went for >1h running; aerobic pace, but still not a pleasure stroll. Let’s say 70% max HR. When I returned home I realized I wanted to take the test, so rushed to the lab and had the blood taken something like 30 to 60 minutes after running. The results were – to me – scary and hard to understand: TC 320, LDL around 200, TG 270. High TG on very low carb? Only HDL stayed where it was, around 100. I will take the test again without shutting the brain off beforehand, but this episode raised a question in my head and I could not find the answer. In my daily work a measurement is a measurement and it has to be understood; so even in this case, apart from claiming that the lab screwed it up, a bias – if any – should be explained and quantified, but not being an MD I do not have the knowledge to do so. Coming to the questions. If I am in ketosis (confirmed by testing myself) I am supposed to use fatty acids as the primary energy source. Right? So, does training in aerobic mode increase the amount of fats in the blood during activity? If yes, how would these fats show up in a test and how long do they stay around after the end of the training session?

Calvin, thanks for sharing.

1. I think the alcohol phenomenon is a real one, and I’ve heard it from many folks. I am not sure exactly why, though I have to believe it has something to do with how the liver processes ethanol and makes B-OHB simultaneously.

2. I’ve done a set of experiments I need to write out that looks at changes in lipoproteins as a function of exercise. It addresses this, but it will be months (years?) before I can get to it. To your first point in this question, Part X of the cholesterol post will address.

Hi Peter,

It appears that much of the research in ketogenic diets involves men. However, I have not done the extensive review of you and your colleagues. In your review of the literature, have you found evidence of gender differences in response to ketogenic diets?

Thank you so much for your refreshing contributions to this field.

Great question. I agree that more work has been done in male subjects, but I have seen research in female subjects, also. You may want to check out the work of Hussein Dashti.

I have been on a ketogenic diet for 2 weeks. At first I felt great, but now I have headaches and muscle cramps. What should I be doing differently? I really want to continue on with this style of eating.

Hi Nancy,

It’s probably because you don’t eat enough sodium. You can read more about it here https://www.proteinpower.com/drmike/saturated-fat/tips-tricks-for-starting-or-restarting-low-carb-pt-ii/

G’day Peter,

I add my vote to the cheap-druNK concept. I’ve been NK for 7 months and I get hit rather hard by a couple of glasses of wine compared to pre-NK.

By the way, thanks for writing your blog – I am an enthusiastic follower.

And your TED talk was up there with the very best.

Thanks very much, Greg.

I just came across your website this week and am very excited to see someone else telling the truth about nutrition! I am a type 1 diabetic and have always been active and in relatively good shape. I have followed Dr. Richard Bernstein’s plan for close to 10 years now. The problem I have is that I want to remain in ketosis, but during training for triathlon and in the actual races, my blood sugar drops rapidly and I have to take a lot of fast acting glucose to avoid a major hypoglycemic event. So, how can I stay in ketosis when I have to take in 60 + grams of carbohydrate per race or intense training session?

One can stay in ketosis and consume more than 60 gm/day of CHO, if metabolic demands are high enough. On my most active day, with enough threshold work, I need to consume 100 gm of CHO per day to perform, and still remain in ketosis.

Hi Peter!

One question I am just really confused about is how can ketosis enhance muscular growth? I’ve been ketogenic and I have gained muscle but this surprises me. In the low-carb community there is much discussion regarding the role of insulin in fat storage but very few also mention that insulin also fuels muscle anabolism. Is it simply that insulin has a much less pronounced effect on muscle than fat? Do other hormones play a greater role in muscle growth? Type 1 diabetics, if left untreated lose massive amounts of fat and muscle. Shouldn’t their muscle be preserved if lack of insulin is the problem? I am very confused on this subject. Your help would be greatly appreciated.

Ketosis may not be the fully optimized state for pure hypertophy, but unlike T1D, a person in NK still has some insulin. Training specificity, and amino acid composition, and genetics, will all play a role.

I am a woman of 74 years but I haven’t seen any reference to the effects of NK on the elderly. I have been on this diet for about 3 weeks now. have lost a couple of kilograms (I am slightly overweight) and feel fine. My cholesterol was a bit high. I’m not sure what it is now. However, my concern is that I have osteopenia and, in some parts, osteoporosis. Can NK harm my bones, i.e. cause loss of minerals? I take various supplements.

Really good question, Marion. I don’t know the answer, since I have not seen any studies implementing NK in the elderly. I think the best thing to do would be get a bone scan (DEXA for bone — ask your doctor for a referral), then repeat in 6-12 months, while continuing to supplement. Of course, the recent post I did should hopefully convince you that NK is not “necessary” to achieve your goals.

Hi Peter:

Great essays and even more so very informative. I continue to reread them to get a better understanding of ketosis.

Various references indicate the brain’s daily need for glucose being from about 120gm falling to 40gm or so once keto-adapted. When referring to the glucose needs of the “brain”, is this the entire nervous system or specifically the mass of the brain within the skull? Further, what is the amount of glucose used for the other areas of the body that continue to rely of glycolysis for energy generation even when keto-adapted, e.g., red blood cells, interior of the kidneys, and whatever else.

By the way, your TED presentation was powerful. I found the virtues driving you as a physician and medical researcher even more significant than the theme of the presentation itself. For inspiration, I send a reference to the presentation to my nephew who is in a PreMed program.

Neurons depend primarily on glucose. The grey matter is one of the most metabolically active parts of the body, on a per weight basis. In keto-adaptation, the brain continues to get about 50% of its energy from glucose.

Thanks, Peter. I was hoping that there had been some research done on NK and osteoporosis. I have been having bone scans every 2 years so will have another one soon. I actually went onto this diet mainly to encourage my husband, 78 years, over weight and pre-diabetic, to do so too. Do you think it will be good for him? He has only lost 1kg.

It probably is, if he has carbohydrate intolerance, which it sounds like he does. Consider reading Phinney & Volek’s book and that of Richard Bernstein.

Hi Peter,

I’ve read about people having rashes (prurigo pigmentosa) in ketosis (nutritional, fasting, diabetes, etc.) where things like increasing carb intake and insulin administration helped (also antibiotics). The cause seems to be unknown, but some “theories” I’ve read are Candida die-off or a Herxheimer effect, and the body detoxifying/releasing toxins stored in fat. I would love to hear your thoughts about this!

Very interesting, though I am not aware of this effect.

I have a question. I lift weights and swim. I am 57 years old. I eat less than 30 grams of carbs a day. I don’t seem to notice a slow down at workout for my swimming workouts which the coach gives me ( Mostly anaerobic). Lifting weights do not seem to be hampered. When I sprint a fifty which might be equal to a 200 in track I do not find my speed dropping at all. So that is my experience with training. I have not swam the 100 lately. Would I be slower ? It is equal to a 400.

Now about nutrition. When I had my whey shakes after workout I began to gain weight, I think body fat. I figured that it was because I was getting to much protein and it was knocking me out of ketosis. I increased the fat and dropped the protein and I stopped gaining weight. But then i read Mc Donald’s work on the keogenic diet. He says increasing fat does not effect ketosis. It is the amount of protein that can effect ketosis. And eating to much will knock you out. A lot of people recomand increasing fat. But if your protein is low enough and you are keeping the fat low will it effect your keto adaption???? (I mean I would do this to loose weight. )

Ketosis is very sensitive to carbs (obviously), but also protein (more than most people realize). I would guess that if your 50 speed is still there, so too will your speed in the 100, especially as you adapt.