As soon as this week’s podcast with Ryan Holiday went up people began contacting me to say how timely it was, if not outright eerie, given it was recorded a few months earlier. Only the day before it was released, we learned about the tragic helicopter crash that claimed the life of Kobe Bryant and his 13-year-old daughter, along with seven other people.

In the podcast, Ryan and I open the discussion with some banter about farm life, for which we both share a fondness. Ryan very eloquently made the point that one of the consequences of living on a farm is the overwhelming familiarity with death that comes with it. And while that sounds morbid, a Stoic might consider this familiarity a gift: by constantly being so close to death, we might not be lulled into a false sense of our own immortality. It’s not that any of us actually think we’re immortal—everyone knows death is inevitable—but for most of us death seems just far enough away that it imposes little urgency on our lives.

And yet, every once in a while, a tragedy like Bryant’s death jolts all of us back to the stark reality of our mortality and the very finite time we have. Death is coming for us all, and we never know when. My close friend, Ric Elias, spoke about his near-death experience aboard US Air flight 1549 as it landed emergently in the Hudson River 11 years ago. He described that experience as the greatest gift he ever received. If you have not heard him explain why, you should do so today.

For perfectly understandable reasons my parents called me this week to beg me to never step foot in helicopter again (helicopter is a pretty common way to get around the Hawaiian islands where I like to hunt) and my wife, who once joined me on a helicopter flight between Maui and Molokai, asked that we never do so again. I get it. I found myself wondering the same thing for a few hours last Sunday as I struggled to contemplate what the final moments of the crash victim’s lives must have been like, and the long tail of grief that remains with their loved ones.

But then I realized I was letting my emotions conflate two issues: the frequency of an accident and the severity of an accident. By frequency, I mean the likelihood of getting into an accident and by severity, I mean the outcome of an accident. If the frequency of an accident is very high (say, stubbing your toe, which happens all the time), but the severity is low (you won’t die from a stubbed toe), the overall mortality rate is low. Conversely, if the frequency of an accident is very, very low (say, getting attacked by a lion), even if the severity is high (if you are attacked by a lion, it’s probably not going to end well), the overall mortality rate is still very low.

The higher the severity of an accident, the more we tend to recoil from the thought of it: being attacked by a great white shark, being struck by lightning, a crocodile ambushing us as we walk past a waterway. And, of course, aviation accidents.

What we should be concerned with, however, is the dot product of severity and frequency (basically, severity times frequency). That is the actual mortality impact. And when it comes to accidents, nothing scares me more for my life and the lives of people I care about than automotive accidents.

Automotive accidents have a far higher frequency than air travel, but a much lower severity (fatality rate). In other words, you’re much more likely to get in a car accident, but the probability of the accident resulting in a fatality is less than 1 percent. But the net effect is clear: the rate of fatal accidents in a car dwarfs that of helicopters or airplanes. It’s a difference of several orders of magnitude.

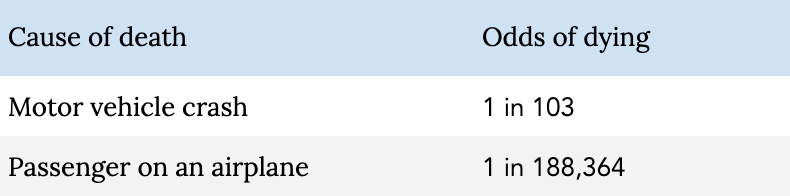

Another way to consider this is to look at the overall odds of death across the span of your life, rather than by hours traveled. Table 1 gives you an idea of how stark the contrast is between driving and flying.

Table 1. Odds of dying in a car vs an airplane. National Safety Council

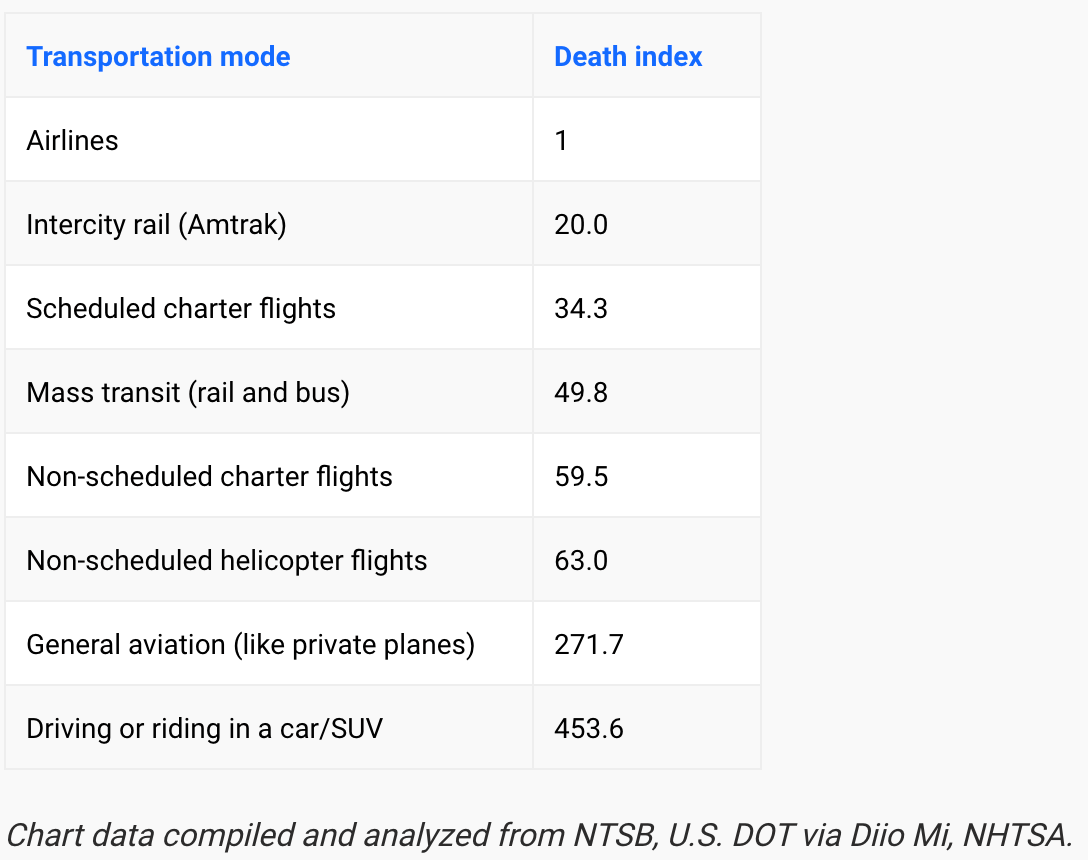

Table 2. Death index for various modes of transportation. The Points Guy

This table suggests that you’re about 450 times more likely to die in an automotive accident than on a scheduled passenger flight. It also suggests that you’re about 7 times as likely to die in an automotive accident than on a helicopter flight of similar distance.

I could go on and on, but I think you get my point. No matter how you look at it, your odds of dying are somewhere between “greater” and “much, much greater” on the road than in the air. This does not mean we shouldn’t scrutinize the hell out of aviation—anything with a high severity of death warrants this—and hopefully in the coming weeks the circumstances of the crash that claimed Bryant’s life will lead to better procedures and protocols to reduce the risk further for all subsequent air travelers.

But it would be wrong to suggest Bryant was taking too much risk for his frequent use of helicopters. Just ask anyone who has tried to drive in, let alone live in, a city like New York or Los Angeles. Had Bryant never stepped foot in a helicopter, and instead only driven, we have no idea if a fatal accident would have not already claimed his life on the 405 or elsewhere.

Which brings me to the most important point I can probably make today: It’s a good idea to be a bit afraid every time you get into a car. Maybe not as afraid as I am, but at least someone on guard.

Next week I will walk you through how I channel this fear, because fear without a plan is of little value. Fear with a plan is a gift. There is zero assurance that what I do in a car will keep me alive—I am probably more likely to die in a car over the next decade than from any other cause—but I do think I can reduce the odds by quite a bit, and I’d like to share my insights with you.

Thanks very much for this. My understanding (simply reading the news) was that visibility at the time was poor and that the helicopter did not have some safety equipment that might have reduced the risk. They made a decision to fly at a time that was riskier. Just like choosing to drive when roads are icy because you want to get home for Christmas, or not following the two second rule when driving, people make decisions that increase risk. I’m very interested to learn more about this tragic accident in hopes that the NTSB can help prevent future accidents. My parents are both retired physicians. They apparently spent plenty of late hours in ERs. As a consequence, I wasn’t allowed in high school to be out after 11:00 because as they explained my chances of being in a serious car crash more than doubled. Sorry for the long comment. Huge fan.

Hi Peter,

Thanks for this. Your outlook is sound and helps many to take a rational view on these things.

I know from your cycling background you also understand we road cyclists are at great risk every time we hit the streets. Even more so in this age of distracted driving. Statistics like these are scary, yet we continue riding:

https://www.usnews.com/news/healthiest-communities/articles/2020-01-28/bike-fatalities-hit-25-year-high-in-california-rise-nationwide

Are we crazy? Maybe a little, but as you point out the statistics are in our favor. It’s just that when there is a car-bike collision, the cyclist is at great risk for severe injury or death. So while different in the horror, it’s similar to plane and helicopter crashes in that the family receives such tragic news and the life of a person was ended needlessly and abruptly.

There are things cyclists can do to reduce the chances of being hit by a car. Cyclists like protected lanes and trails, but they’re not always available. I think a road cyclist should be as conspicuous as possible (e.g. use daytime front/rear lights and wear bright clothing) and ride defensively, honoring traffic signals and signs and other rules of the road, etc.

All these things will help but still doesn’t reduce risk to zero. Neither does sitting in one’s couch all day of course, so we mitigate risk as we can while we follow our various passions.

We appreciate your voice, and your guests, on all the things you speak about on your podcast (esp. love the longevity stuff!). Keep on, and to all on your bikes, keep the helmet side up and rubber side down!

Cheers,

Tom

Peter,

Next to nothing is known about the actual crash, and I’m not trying to comment on that situation. However, as a flight instructor, “VFR into IMC” is generally recognized as the most dangerous of all flight regimes. “Special VFR” often devolves into exactly that situation.

It would be very interesting to see your accident statistics for the narrow case of “VFR into IMC”.

Thanks for an excellent blog.

Peter,

Your point about traffic accidents can’t be overstated. It’s a risk that most people do not take as seriously as they should.

That being said, Bryant made a fatal error in judgment by getting on that chopper. He took off in dense fog that purportedly grounded police helicopters. This error in judgment makes the crash no less tragic for his family, friends and fans, as well as those of the other passengers, but I believe it needs to be repeated and stressed.

My observation is that the rates are to varying degrees heterogeneous and should be stripped of fatalities due to controllable factors such as self inflicted automotive fatalities, the driver and passengers but not others hit by the vehicle.

Kobe’s death and those with him are an unnecessary addition to the statistics. No sensible pilot would have flown that day and had they flown they would have set down in Burbank after seeing the conditions. Furthermore Kobe as a frequent flyer had an obligation to understand the risks and limitations of the machine he was using and of flying in general. In general in flying there is a term, Get There Itis. GTI it’s a known pilot killer and so is flying VFR into IMC conditions. Unfortunately those Pilots who make these poor decisions tend to take with them innocent people who didn’t understand the risks and put their trust in a particular persons judgement or in this case personality that what they were doing was sensible.

When teaching me how to drive, my dad told me to always expect people to do the unexpected on the road so you’re ready to defend and rebound. I’m so grateful to him for sharing this simple, yet extraordinarily useful wisdom with me.

I think that part of the shock is the idol phenomena. We place some athletes, actors and public figures in a pedestal, larger than life. A surprising mundane event like death, which happens every day to millions of people, knocks them out of the pedestal and forces everyone to face their humanity.

I found this interesting. Opposite conclusion and, probably, both right. Looking forward to something a little more actionable. Thanks!

https://www.medpagetoday.com/publichealthpolicy/generalprofessionalissues/84627?xid=nl_mpt_blog2020-02-03&eun=g516042d0r&utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=ItsAcademic_020320&utm_term=NL_Gen_Int_Its_Academic_Active

Your distinction between frequency and severity of risk is particularly apt concerning the 2019-nCoV epidemic. Some viruses infect a large number of people but have a comparatively low mortality rate. Often the disease is spread by those with few or no symptions. Other viruses have a high severity and mortality but infected patients die before spreading. Influenza, for example, infects and kills more than other viruses (high frequency) even with lower severity. MERS and Ebola are the reverse.

It is important to determine the relative risks of 2019-nCoV of frequency and severity. More accurate numbers are coming in as diagnostic and antibody tests become available. Early numbers emphasize severity with uncertain frequency.