I recently read an encouraging perspective in JAMA titled, “In Alzheimer’s Research, Glucose Metabolism Moves to Center Stage.” The article points to accumulating research suggesting glucose hypometabolism in the brain is not just a marker of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but a maker of it. I say “encouraging” because for about a decade there have been scant voices suggesting that AD had a strong metabolic component—I remember giving a talk at the University of Minnesota in 2012 to a room of bemused onlookers summarizing the work of leaders in this space—so to see a preeminent medical journal giving this space its due is a step in the right direction.

The perspective highlights the observational studies that suggest patients with diabetes (particularly type 2, T2DM) have an elevated risk of developing AD and other forms of dementia (with vascular dementia showing the highest association in this meta-analysis).

A different line of research shows that different variants of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) allele affect glucose metabolism in the brain in mice. Essentially, mice with two copies of the APOE2 variant are more efficient at utilizing glucose than APOE4 mice, which could help explain the associated protection of the APOE2 variant, and elevated risk of APOE4 seen in study after study in the US population.

The perspective closes with a section on testing diabetes drugs among patients with AD and other forms of cognitive impairment, as well as a few studies looking at whether diet and exercise might delay cognitive impairment.

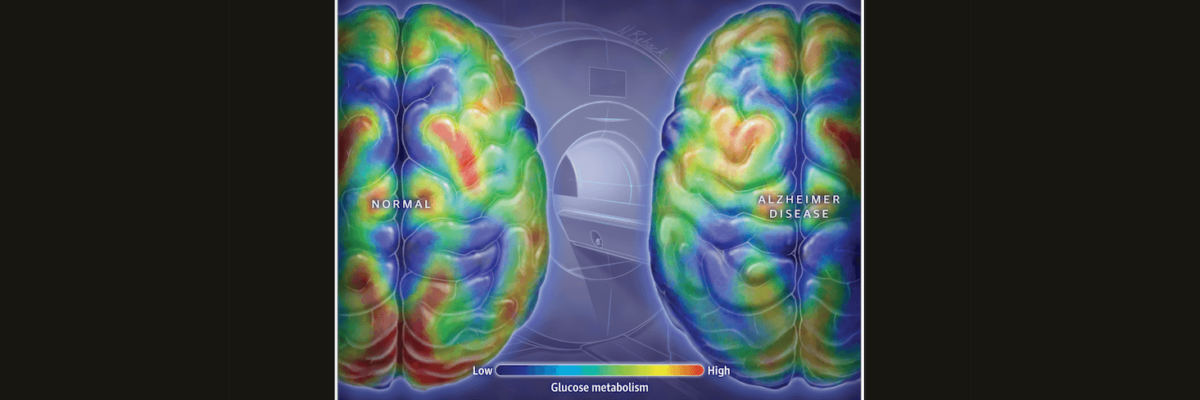

All of this suggests that there’s a metabolic component to AD, and effective treatments for diabetes may also help treat AD. If T2DM increases the risk for AD, lowering the risk of T2DM may lower the risk of AD as well. Perhaps more importantly, a study looking at positron emission tomography (PET) scans of people at high risk for developing AD have detected decreases in the rate of glucose metabolism in the brain decades before the appearance of AD symptoms. If we can detect abnormalities early, we can address them early.

I’ve discussed AD as a metabolic disease on the podcast with Richard Isaacson, a neurologist and director of an Alzheimer’s prevention clinic, and Francisco Gonzalez-Lima, a professor of neuroscience and AD researcher, and both of them believe metabolism is a key player in the prevention and treatment of AD. Please check those out if you want to learn more about potential strategies and tactics to reduce the risk of AD from a metabolic perspective. It’s encouraging to see more resources focusing on brain energy metabolism to reduce the burden of such a devastating disease and to see a high-profile outlet like JAMA reporting on it.

– Peter