One of my readers posted a link to this short talk from TED Talks Education. (You’ll want to watch it to understand the rest of the post.)

I found the talk interesting, and in the talk Ms. Duckworth makes a reference to a Stanford psychologist, Carol Dweck, who has been very influential in my thinking about children and childhood learning. In fact, when I became a father one of the first books I read (and have since recommended to every parent I know and even my daughter’s kindergarten teacher) is a book by Dr. Dweck, Mindset.

Now, I don’t know if everything Ms. Duckworth says or suggests is correct. Her work is well outside of my area of knowledge. But it’s a topic I think about so much, and since watching this video I’ve been reflecting on my life and the implications of this idea to our health.

First, some background

Shortly after my twelfth birthday, boxing fans around the world were given a gift unlike anything before or since, the showdown between Marvelous Marvin Hagler and Tommy Hearns (don’t watch this unless you can handle a violent boxing match). To this day most boxing experts agree the first round of that 3 round war remains one of the — if not the — greatest round in boxing history. I was a huge Hagler fan, and this fight galvanized in me two things:

- I wanted to be a professional boxer (something I pursued relentlessly enough to nearly forgo college), and

- I wanted to be just like Marvin Hagler, the grittiest fighter of my generation.

You see, I was not the fastest when it came to hand speed or foot speed. My punching power was good, but not George Foreman or Sonny Liston good. There was no special “gift” or talent I had that was ever going to make me the next Mohammed Ali or Mike Tyson. But, Hagler didn’t seem to possess any God-given ability and, in my 12-year-old opinion, he was the greatest fighter on Earth. Sure, Sugar Ray Leonard was the media darling and wealthiest fighter of the era, but Hagler was the grittiest. (Anyone tempted to point out that Leonard was awarded the split-decision over Hagler when they met in 1987 need not bother. In my mind – and the mind of many — Hagler won 115-113. If you want to read more, here’s a great summary.) He out-trained everyone. He never got out of shape between fights. He was always ready for combat. He was pure grit.

So, this became the defining feature and mantra of my youth. No one was going to out-grit me. I would run 6 to 10 miles at 4:30 in the morning (imagine how dark and cold that was in Canada) because I knew the other guy was still sleeping. I did 400 push-ups every single night (except one night in 11th grade when I was too sick to move) before bed from age 13 to 18 because I knew the other guy would not.

When I did decide, ultimately, to go to college instead of pursuing a career as a professional fighter (something I attribute to the most influential teacher in my life), it was such an easy transition, because I had already built a mental and emotional infrastructure of grit.

Perhaps because of some deep insecurity I always felt the need to out-grit everyone at everything, even surgery. In residency, while my peers would (rationally) try to catch a nap any time there was a free moment during call nights, I would practice anastomosing 3 mm Dacron grafts together with 8-0 proline, over and over again. I even built a model heart with a deep mitral valve to practice – a hundred times a day – one of the most difficult stitches in surgery, the “A-to-V” and “V-to-A” sutures through the mitral annulus.

You get the picture. I was (and remain) a freak. The ‘why’ is beyond me, though I’ve never stopped trying to understand it. Even when my daughter was only 5, I spent a lot of time talking with her about ‘mastery’ and the joy that comes from the journey of mastering a skill (versus the need to seek pleasure in the outcome or final result). This is not a natural phenomenon and I think, unfortunately, most of our education is based on the result and not the process.

I’ve read countless books on this, both out of desire to better myself and out of a desire to ignite this spirit in my children, and to date the best one I’ve read is The Talent Code, by Daniel Coyle. It’s the only book I’ve ever read where the moment I finished it, I turned to the first page to read it again. In this book, Coyle argues that grit – practice – may not be enough. It’s necessary, but not sufficient for mastery. The other component essential for mastery is the right kind of practice — deliberate practice. This topic is worthy of a book, of course, and not just a few sentences, but suffice it to say, deliberate practice is a very specific type of practice that leads to change. Mastery. While I disagree with this writer’s view that the book, Talent Is Overrated does a better job explaining the concept than The Talent Code, he provides a quick overview for those not familiar with the concept.

How does this apply to our health?

First, if you don’t practice correctly, no amount of practice is going to achieve mastery, whether it’s swimming the 200 IM or playing the piano. A disciplined approach to eating the wrong foods may be better than an undisciplined approach to eating the wrong foods, but it’s no substitute for the correct approach to eating the correct foods.

In 2009, when I was at the height of my unhealthiness – I was overweight, insulin resistant, and had Metabolic Syndrome – it was not because I was not ‘trying hard enough’ to eat well. I had all the grit in the world when it came to eating. I wanted so desperately to be lean and healthy. The problem, of course, was that I was not eating the right foods. It’s the difference between gritty practice and gritty deliberate practice.

Second, let’s posit you figure out what the ‘right’ foods are. Is this sufficient to achieve your health? Well, here I have to include not just my experience, but the experience of my friends, family, and clients. Some people, once introduced to the ‘right’ foods, experience almost an immediate change. The pounds melt off. Their biomarkers improve seemingly overnight. They feel rejuvenated and renewed.

Let me assure you, these folks are the exception and not the rule. For most people the pattern of going from metabolically broken to fixed, which often includes a loss of fat mass, is very slow; slow enough that on a day-to-day and even week-to-week basis it seems negligible.

To explain this, I’ll use fat mass as an example, since it’s the metric most people understand best. In my experience, outside of profound caloric restriction or outright starvation, the typical amount of fat loss I see in a person is about one pound per week, or about 60 g per day. That might not sound like much, and over a week or day, it’s not. (Though, hold 60 g of almonds in your hand and imagine a net loss of this much fat every day from your collective fat cells, and you can start to appreciate how impressive it is physiologically!)

But, we can’t track fat mass directly, at least not on our bathroom scales, and frankly not even with DEXA scans unless they are really spaced out. Certainly not at the level of a few hundred grams. Furthermore, our bodyweight – what we typically do track – fluctuates a lot. In me, for example, it fluctuates by 5 pounds per day. How, you ask? Water. Not just the difference between what I drink and what leaves my body (urine, perspiration, respiration), but also interstitial accumulation, which manifests as minute amounts of swelling, typically in muscles, and elsewhere, too, often in response to exercise, travel, stress, and even foods I eat.

So, if your bodyweight can fluctuate 5 pounds in a day, is it possible to track 60 g per day of net fat loss? It’s like me blindfolding you and putting 50 pennies in your hand and asking you if there are 49, 50, or 51 there. No chance. Furthermore, 60 g is so far outside of the measurement spec of a bathroom scale that even if your weight did not fluctuate much due to fluid shifts, you would never be able to appreciate the net fat loss over the course of a few days and barely over a week.

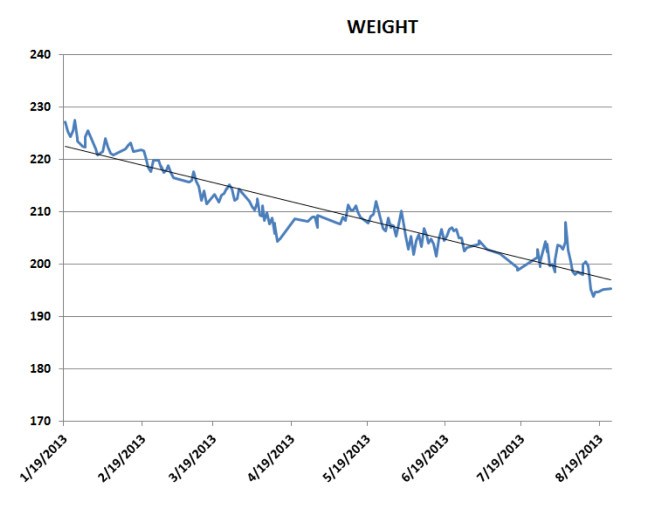

What does this look like in real life? Consider the graph, below, which shows the actual (and completely achievable) weight loss of a person over 7 months. This person went from 227 lb to 195 lb in 7 months, which represents an average of about 4.6 lb per month, or about 69 g of net fat loss per day (as confirmed by DEXA). This was not a starvation diet or something radical. This was a change in macronutrients – from a standard American diet to a ketogenic diet — that led to a change in net fat flux. But, the change is subtle over any short period of time. It’s only over months that the change becomes life-changing.

Now, imagine the day-to-day frustration this person (I know, because I was working with this person) experienced with the fluctuations in scale readings! It was tempting on many occasions to say, “Forget it, I’m going back to what I was doing before.” Just like there were many days I didn’t feel like going to swim practice, or days I didn’t feel like deliberately practicing my surgical technique.

If you remember nothing else, remember this: the game is won – or lost – not by the infrequent big changes, but by the frequent, deliberate, and repeatable small ones. This is where grit comes in.

Sure, there are genetic freaks and lucky ones out there, for whom none of this matters. But for the rest of us – because we live in, and are surrounded by, a food environment that is chronically toxic to about two-thirds of us – re-building our bodies requires consistent and deliberate change.

Are there people with all the grit in the world who can’t achieve health? Absolutely. And I put them into two categories:

- Those who are not eating the ‘right’ foods for them (recall: I was in this camp until 2009).

- Those who have underlying issues – usually hormonal – which are working against them and preventing their fat cells from liberating fat.

I will not get into these categories in great detail, because the topic is beyond the scope of this post and, frankly, it takes me months to diagnose this in people I work with weekly. So I can’t responsibly spout out blanket statements about ‘fix this’ or ‘fix that.’ However, far and away the most common causes I encounter in my practice for persistent metabolic derangement, often but not always accompanied by adiposity (excess fat), in the presence of seemingly correct eating and true grit are as follows:

- An insulin resistant and/or hyperinsulinemic person eating foods that stimulate significant amounts of insulin;

- Hypothyroidism (in my book, TSH > 2 accompanied by basal morning axillary temperature below about 97.8 F);

- Hypogonadism in men (which I diagnose with not only total testosterone, but also free testosterone, DHEA, and estradiol), or PCOS in women;

- Disruption of the HPA axis, most commonly manifested by “adrenal fatigue” and/or elevated cortisol levels.

Again, I’m not going to get into the nuance of these, but I list these to give those folks who believe they are A) eating the ‘right’ foods, and B) full of grit, yet not seeing results, some hope. These issues are fixable, but you need to see a doctor who knows how to fix them.

Fortunately, such situations are very rare! Most people, with the correct dietary intervention, armed with sufficient grit, and the confidence to stay the course, despite the day-to-day and week-to-week fluctuations, will emerge as renewed people.

Parting shot

Unfortunately, as long we live in a world where (i) the conventional wisdom, (ii) dietary recommendations, and (iii) the market forces enabled by them create an eating environment that is not suited to what most of us should eat, we need to guard against the desire to give up when the results are not what we expect in the timeframe we expected. As a result, about 90% of people who make a dietary change – and even see results – end up gaining the weight back. Why? I suspect it’s a bit of what I’ve written about here, and two other phenomena:

- The fall-off-the-wagon-and-get-discouraged issue, and;

- The I’m-better-now-I-don’t-need-to-do-this-anymore issue.

In the former, folks get very discouraged when they make a ‘mistake.’ Rather than immediately getting back on the program, they get frustrated, and over time – sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly – revert back to their old eating habits.

In the case of the latter, there is this belief that once the goal is achieved, one need not continue the practice. It’s like me training for a year to win a time-trial race on my bike, winning the race, and then deciding I don’t need to train anymore and I can still compete successfully. Not going to happen. If I want to win, I need to train. If I’m going to train, I need to train deliberately and persistently. Even on the days I don’t want to. When I miss a workout or have a bad one, I can’t beat myself up over it. I have to let it go and remember that tomorrow is a new day. The sum of my days determines my success.