I remember one of my mentors in surgical residency made a very important distinction for me. He said, “Peter, never forget what you are getting paid to do, and what you are doing for free.” You see, there are some aspects of being a surgeon that are not particularly enjoyable. The hours are long. Sometimes you’re asked to intervene in a situation where there is no hope, and you feel you may only make things worse. A lawsuit is just around the corner. But there are many aspects of surgery that are pure bliss. Though I’m no longer a surgeon, some of my fondest memories in life stem from moments there. Anastomosing a transplanted kidney into a patient (especially the renal vein anastomosis, which is the easiest to screw up). Endartarectomizing a plaque-filled carotid artery. Telling a patient and their family that you were able to remove the entire tumor in their colon, and that the lymph nodes were free of tumor.

Want to learn more? Check out our article on replacing sugar with allulose and our Ask Me Anything podcast all about sugar and sugar substitutes.

What my mentor was saying to me was that those moments of pure bliss are not what we’re getting paid for. In fact, we’d probably pay to do them! What we’re getting paid for is the time we have to be away from our family. The long hours, smelly call rooms, and bad hospital food. The cost of medical malpractice insurance.

What does this have to do with the toxicity of sugar? Well, nothing actually. But I constantly remind myself of this when I feel my personal stress and anxiety mounting. The past year has been a whirlwind of kinetic energy that makes my days in residency, 80 to 100 hours of work every week, seem tame and almost boring. Most of what I do today is wonderful, but some is not. I fly about 12,000 to 15,000 miles a month (in coach, no less) and spend about 8 to 10 nights a month in hotels. Red-eyes are a regular part of my existence. My day starts between 4:45 and 5:00 am and goes until 11 pm or later. I can’t put in words how much I detest traveling and being away from my family. So, I guess, that is exactly what I get paid to do. (By the way, do not feel sorry for me. I’m pretty sure all of this is self-imposed, but I still hate it.)

So, do you want to know what part of my role at NuSI gives me bliss that rivals the finest moments of surgery? It’s exactly what I did a couple of weeks ago (and, fortunately, something I get to do often). I spent a day with some of the best and most thoughtful scientists talking about their work and how we can make it better.

Can you imagine (assuming you’re as much a geek as I am) getting to pick the brains of the best scientists for hours on end? Finding out why they are obsessed with the questions they ask? What keeps them up at night? What are the challenges they face? What’s preventing them from resolving uncertainty?

I would pay to do this part of my job. This is the bliss described by Joseph Campbell. And this meeting a few weeks ago was a great example of it. This particular meeting focused on sugar research, specifically the metabolic impact of sucrose, high fructose corn syrup (HFCS), and fructose. If you need a quick refresher on the distinctions, this should help. Spending so much time with this group got me thinking about a broader issue, which is actually the focus of this post: Is sugar toxic?

What does ‘toxic’ mean?

Before we dive into the main focus of this post, we need to get crystal clear on our semantics. Too much tomfoolery has already taken place for the simple reason that many people don’t understand the words they use.

For the purpose of rigor, let’s turn to the pharmacology literature for a clear understanding of toxicity. Even though we all have an understanding of what “toxic” means, let’s be sure we’re understanding the nuance. If you troll the medical textbooks you’ll eventually settle on a definition something like this (from Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine):

TOXICITY: The degree to which a substance can harm humans or animals. Acute toxicity involves harmful effects in an organism through a single or short-term exposure. Subchronic toxicity is the ability of a toxic substance to cause effects for more than one year but less than the lifetime of the exposed organism. Chronic toxicity is the ability of a substance or mixture of substances to cause harmful effects over an extended period, usually upon repeated or continuous exposure, sometimes lasting for the entire life of the exposed organism.

The first thing you may notice from this definition is that toxicity is actually subdivided into acute, subchronic, and chronic toxicity, based on how long it takes to progress from exposure to insult and the number of exposures necessary to cause insult. This constitutes what I call:

Important point #1 – don’t confuse acute toxicity (what most people think of) with chronic toxicity.

Acute toxicity and the LD50

An example of acute toxicity is acetaminophen (abbreviated APAP, but commonly referred to by its trade name, Tylenol) overdose which, if significant enough, requires a liver transplant within days to prevent death from fulminant liver failure. (As an aside, this is particularly tragic because the liver, unlike the heart, lungs, and kidneys, can’t be supported extracorporeally; so if a person overdoses, and the liver is irreversibly damaged, they will need a liver transplant within days, or they will die.)

The question, of course, is what dose of APAP is toxic? (In this case, the toxicity is liver failure, which results in near-immediate death.) Enter the LD50. LD50 stands for “lethal dose required to kill 50% of the population.” How is this quantified for a given substance, including APAP? Obviously, we don’t do randomized trials of increasing APAP doses in people until we definitively resolve this. Instead, we (I’m using ‘we’ pretty liberally here – obviously I have never done this) do 3 things typically:

- Carry out the above experiment in animals to accurately estimate LD50 (in the animal);

- Mathematically model the best human data available and try to estimate LD50 (in humans);

- Compare the two estimates.

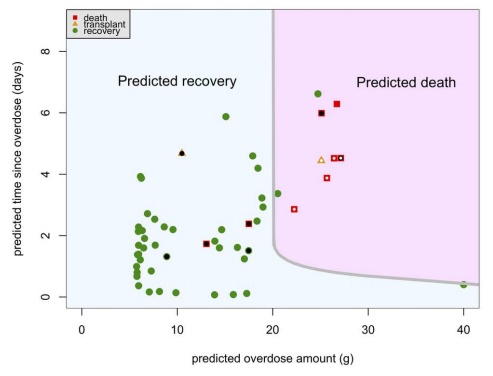

Not surprisingly, the answer to #1 is usually much higher than the answer to #2. In the case of APAP, the LD50 in rats depends on age, but is probably somewhere between 800 and 1,500 mg/kg, suggesting a 75 kg human would expect toxicity (on average) between 60 and 110 gm (120 to 220 extra strength Tylenol tablets!). Is this likely? Let’s go to step #2. Below are data integrating known human toxicity with a mathematical model to estimate LD50, as a function of APAP dose (x-axis) and death versus survival over time (y-axis). As you can see, this analysis suggests LD50 in humans is closer to 20 gm. (These are data from humans who did not undergo liver transplant, except in the case of the yellow triangles.)

I’ve looked at several other models and they all appear to suggest about the same thing, The LD50 of APAP in humans is about 10 to 20 gm (10,000 to 20,000 mg or 20 to 40 Extra Strength Tylenol tablets), and most sources point to the lower end of that range.

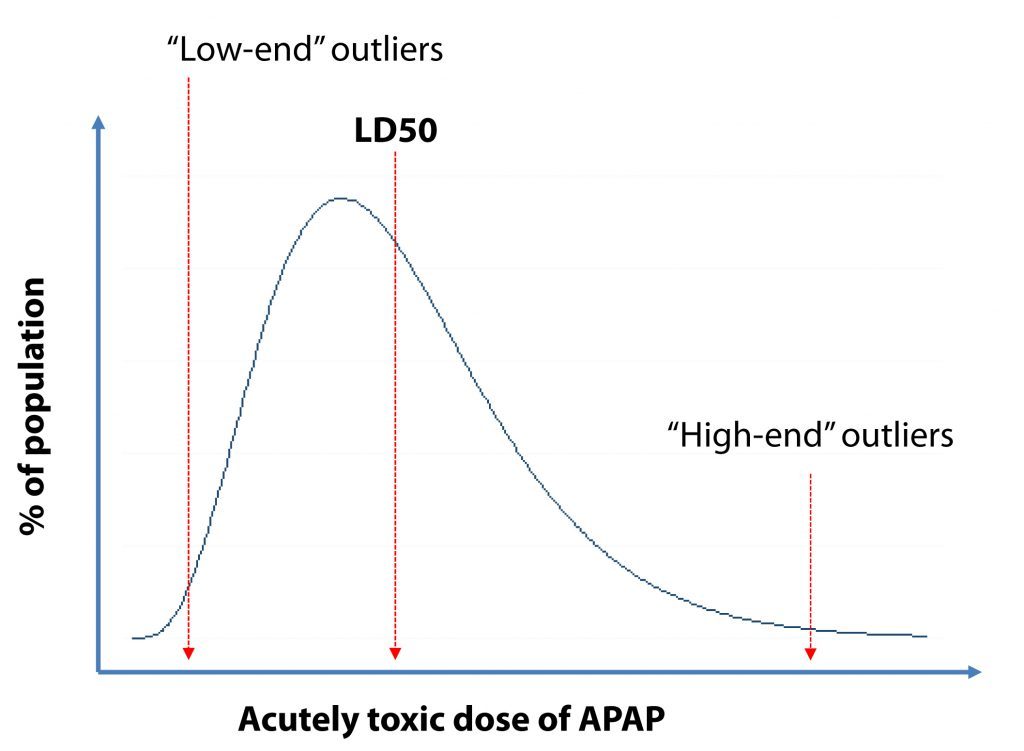

So what’s my point of this? My point is that there is a statistical distribution (see figure below) of the toxicity, which is why it’s called LD50 and not “LD” (which would imply everyone would experience toxicity from the same dose). In other words (let’s simplify and ignore weight differences since this is in mg/kg and just assume I’m talking about a 75 kg human), some people will experience toxicity at 6 gm and others not until 16 gm. In the figure above, you can see one person lived, despite a dose of 40 gm (given that he received the antidote early enough) and another at 25 gm, without antidote.

Important point #2 – there is a spectrum of susceptibility to any toxin.

What about chronic toxicity?

Sticking with APAP as our example, it turns out that much lower doses than the LD50, if taken day after day, are also toxic to the liver. How much lower? As you’ll see below, the answer is highly dependent on the timing of these doses and other host factors. In general, though, some authorities suggest repeated daily doses of more than 6 gm are toxic, while repeated doses below 4 gm daily are rarely toxic. The point is that much smaller doses, if taken repeatedly, are still toxic.

Important point #3 – just because a dose does not result in acute toxicity does not mean it can’t or won’t cause chronic toxicity.

Complicating things a bit further…

There is no reason to expect physiology to be simple or binary, so adding one more layer of nuance to this already-longer-than-you-wanted-to-read-explanation is the following point. Factors such as alcohol consumption, underlying liver disease, viral infections, and genetic susceptibility are highly influential in both acute and chronic toxicity from APAP. This shouldn’t be surprising, of course, though it complicates our discussion. Since APAP taxes hepatocytes (liver cells), taking other drugs that do the same, consuming alcohol (uniquely metabolized by hepatocytes), or having underlying liver disease are invariably going to reduce hepatic reserve. So, an individual’s ability to tolerate APAP is highly dependent on both measureable (e.g., cirrhosis) and idiosyncratic variations.

Important point #4 – host factors play a significant role in susceptibility to toxins.

Parting shot

I would be surprised if anyone reading this has not taken or used APAP (i.e., Tylenol or some generic equivalent). In fact, most of us have experienced great relief from it. That does not change any of the points above.

Important point #5 – the term “toxin” does not imply something is “bad” or universally harmful.

What does APAP have to do with sugar?

There must be some reason I’ve gone through all of this, right? After all, the question of sugar’s toxicity is a somewhat polarizing one. On the one hand, folks like Dr. Rob Lustig have argued that fructose is harmful at the doses most people are consuming it today. On the other hand, folks like Dr. James Rippe have argued the opposite. Having read just about every paper and review article on this topic (I think) over the past year, I can say the debate has many facets, which I’ll outline briefly:

-

- The PRO sugar folks** argue that sugar, while void of any nutritional value, is no more or less harmful than a calorie of any other nature. In other words, it has no unique metabolically harmful consequence.

- Depending on affiliation, some of the PRO sugar folks debate back and forth about the advantages or disadvantages of sucrose (natural sugar from beets, cane, etc. composed of a linked glucose and fructose molecule) and HFCS (synthesized sugar composed of 55% fructose, 45% glucose mixture). (There may be some merit to this discussion, though it would probably qualify as a “higher order” term. To a first or second order approximation, they are biochemically equivalent.) It appears this debate is a convenient way to avoid really confronting question/point #1. The “natural sugar” producers can point at the corn growers, and vice versa, without really confronting the jugular question. Both of these groups (sugar and corn) downplay research on pure fructose (which is pretty rare in nature and even our current environment), which is a valid point, though a distraction from the issue above.

- The ANTI sugar folks argue that sugar is indeed a “unique” macromolecule distinct from other carbohydrates. Whether solely due to the fructose content, the combination of fructose and glucose, and/or the kinetics of the fructose (i.e., the speed with which the fructose requires hepatic attention when not accompanied by fiber) is a matter of debate and speculation, but those in this camp do agree that sugar is not “just” an empty calorie. The toxicity of sugar, they argue, is primarily related to its hepatic metabolism. Specifically, “excess” (see below) ingestion of fructose increases VLDL production which increases apoB or LDL-P due to greater triglyceride load. Additionally, at least at reasonable doses according to most literature, insulin resistance is worsened which amplifies the harm caused by other foods.

- Even among those who don’t subscribe to the idea that sugar is metabolically unique (and harmful), with or without a dose-effect, some argue that fructose consumption impacts subsequent food consumption in a way that glucose does not. In other words, eating sugar may fail to satiate you and/or make you subsequently hungrier. These data are sometimes confounded, as are many data in this area, by the use of pure fructose, rather than the glucose-fructose mixture found in sugar. Furthermore, evidence is emerging that sugar is addictive, much in the same way that a drug like heroin or cocaine might be, as suggested by functional MRI. So, while folks in this camp argue that sugar per se isn’t harmful, it does make you eat more (sugar and non-sugar, alike), and that is the harm.

- Perhaps the largest debate in this area stems from the dose issue. The PRO sugar folks argue that at the doses most Americans consume sugar, there is no harm (even if there is a theoretical harm at very high doses). The ANTI sugar folks argue that there is a dose-dependent (and probably a context-dependent – e.g., the insulin resistant person vs. the insulin sensitive person) deleterious impact of sugar, AND that current consumptive patients are indeed in this zone of toxicity. (This is probably the most comprehensive single review I’ve read on the entire topic, and I’ve discussed it point-by-point with 2 of the 3 authors.)

- Speaking of the dose issue, no area of this debate (in my opinion) has generated so much controversy. How much sugar, defined as added sweetener (so this does not include the fructose found in fruit, for example) do Americans actually consume? This is important, of course, if we want to know how applicable the above studies are to the question at hand. Where to begin? (This topic alone is really a 3-part blog post.) Estimating how much added sweeteners Americans consume is primarily done via two methods:

- Taking the difference between food availability data and waste data (ERS); or

- Using nutritional surveys (NHANES).

One of my colleagues, Clarke Read, looked into this recently. Here is what he found (this was in response to a recent NY Times article suggesting sugar consumption is less than typically reported):

The adjustment to loss rates was done by RTI International in this report to the USDA Economic Research Service (ERS). Section 4-1, which is an example calculation, is most useful. RTI was asked to calculate estimates of loss, not estimates of consumption, and rather than working down from availability data, they in fact used NHANES 2003-2004 data to estimate consumption, then basically compared this to availability numbers (with a few adjustments) to find amounts of loss. These loss percentages calculated from 2003-2004 then became the standard, and all other consumption data was calculated by applying this % loss to the availability data.

This means that all consumption numbers are effectively derived from NHANES data. This is especially relevant for added sugars. Since NHANES data tracks only consumption of foods, not ingredients, this availability-versus-consumption comparison initially leads to a 96% loss of cane and beet sugar (seen on page 95 of the 2011 USDA document — the “4 percent” referred to in the NY Times article), since NHANES data only reflects sugar added to foods directly, rather than used as an ingredient. The judgment of a panel of experts was then used to determine the percentage of available sugar used as an ingredient, which led to their 34% loss estimate for sugars. For HFCS, which is never consumed as a food and always as an ingredient, they simply gave it the same value as honey (15% loss between availability and consumption). The ERS, however, overruled them (as described in the NY Times article — see the end of the Losses at Consumer Level section in the link for ERS evidence) and used the 34% loss estimate instead.

Page 10 of the 2011 USDA document shows who these 6 experts are. The NY Times article asked 2 of these 6 about these sugar estimates, who don’t recall making them, though it’s implied that they simply don’t remember what happened back in 2008. In other words, while the overall trend in sugar data is determined by availability data (since % loss is assumed to be constant over time), the absolute amount consumed on any given year, as estimated by these loss-adjusted numbers, is entirely dependent on this RTI loss estimate which, for added sugars, is almost entirely dependent on an expert’s estimation. All foods that are primarily consumed as foods rather than as ingredients have consumption levels that are based on an extrapolation of 2003-2004 NHANES data.

Translation: this is a complete cluster. If you triangulate between the ERS and NHANES data, you wind up with an estimate of about 90 pounds of added sweetener per person, per year, or about 110 gm per day which, on average, works out to about 15% of total caloric intake. Of course the actual consumption is much more nuanced (what isn’t?), since consumption varies a lot by age, gender, and socioeconomic status. Furthermore, this estimate doesn’t include the fructose in fruit juice or fruit, though the latter probably isn’t nearly as high, or relevant, as the former.

Another very interesting point uncovered by colleague, Clarke, was that in a 2009 paper in The Journal of Nutrition, Dr. James Rippe (one of the leading proponents of sugar) noted the following:

“…fructose, as a component of the vast majority of caloric sweeteners, is seen to be particularly insidious.”

“It has also been shown to increase uric acid levels, which in turn promotes many of the abnormalities seen in the metabolic syndrome including hypertriglyceridemia.”

“There is considerable evidence of a detrimental effect on metabolic health of excess fructose consumption.”

Whether by accidental omission or otherwise, this paper is not listed on Dr. Rippe’s CV on his website.

**Sadly, it’s difficult to really interpret the data objectively from those in the PRO sugar camp because of the conflicts of interest. Most of the PRO sugar scientists are heavily funded by the sugar industry. For those interested in the historical context on science and the sugar industry, you’ll find this article particularly interesting.

Take home messages

What I find frustrating about this debate is that most people yelling and screaming don’t fully define the terms, perhaps because they don’t appreciate them (forgivable) or because they are trying to mislead others (unforgiveable). The wrong question is being asked. “Is sugar toxic?” is a silly question. Why? Because it lacks context. Is water toxic? Is oxygen toxic? These are equally silly questions, I hope you’ll appreciate. Both oxygen and water are essential for life (sugar, by the way, is not). But both oxygen and water are toxic – yes, lethal – at high enough doses.

What did the APAP example teach us? For starters, don’t confuse acute toxicity with chronic toxicity. Let’s posit that no one has died from acute toxicity due to massive sugar ingestion. But, what about chronic toxicity? Can eating a lot of sugar, over a long enough period of time, kill you (presumably, through a metabolic disease like diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, or heart disease)?

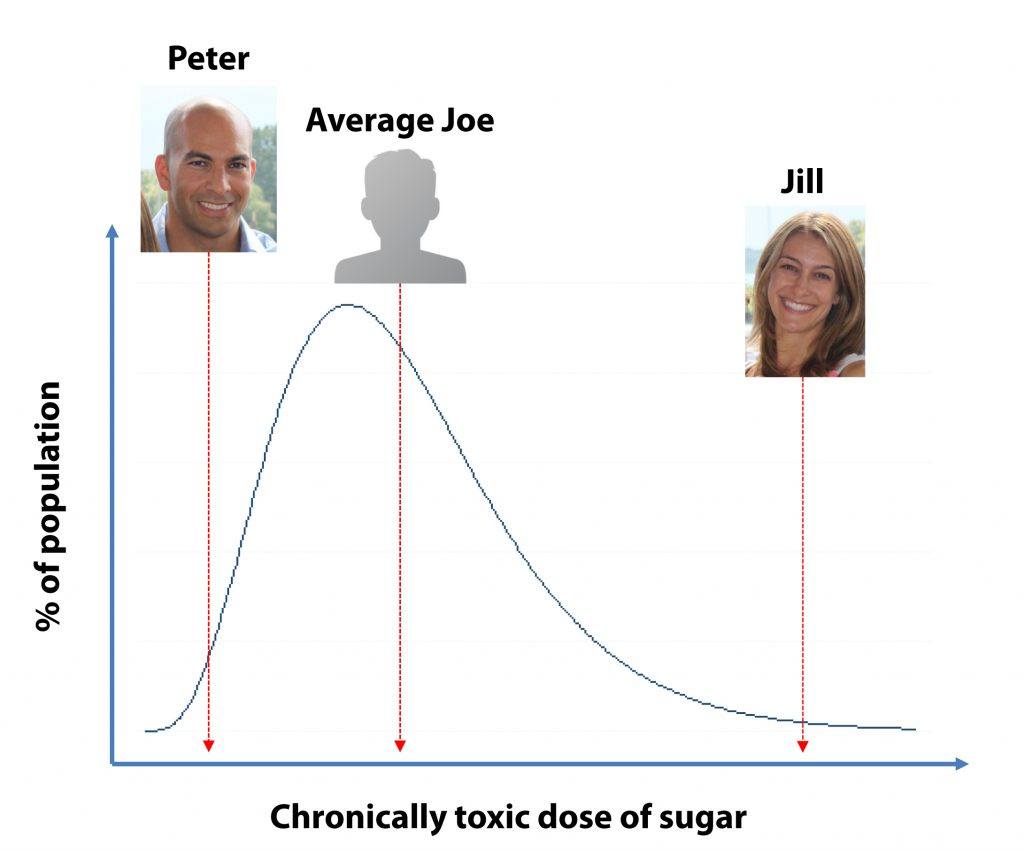

Even among a healthy population (i.e., people without overt liver disease), toxicity is a distribution function. What’s toxic to one person may not be toxic to the next. This is true of APAP and it’s true of sugar. It’s true of most things I can think of, actually, including tobacco, alcohol, cocaine, and heroin. Ever wonder why “only” about one in six smokers dies of small cell lung cancer? Maybe it’s the same reason some people (e.g., me) get metabolically deranged from even modest doses of sugar, while others (e.g., Jill, my wife) can mainline the stuff and not appear to suffer many adverse effects.

I posit that Jill and I are both outliers on the distribution of susceptibility, probably driven mostly by genetic difference (rather than, say, exercise as we both exercise a lot). So, I offer you a framework to consider this question. I know some of you just want an answer to the question, Is sugar toxic or not? But I hope this slightly more nuanced response can help you figure out what you should be asking: Are you like me? Like Jill? Or like an Average Joe somewhere in between us?

This is what you will need to figure out on your own. You could play it safe, assume you’re like me and eliminate all sugar from your diet (I eat no more than about 5 gm of sugar per day, almost exclusively in 85%+ dark chocolate – so less than 4 pounds per year). But if you have Jill’s genes, maybe this is overkill. (Though, I would argue, and may do so in a later post, that even Jill has noticed a change in her energy levels and a number of biomarkers by reducing her sugar content somewhat over the past 3 years.)

It’s pretty easy (conceptually) to figure out where you are on this spectrum, but it does involve a few deliberate steps:

- Without making any adjustment in your current eating habits (i.e., fight like hell to avoid the Hawthorne effect), record everything you eat for a week and, using a database like this one (or something fancier like Nutritionist Pro), calculate exactly how much sugar you consume.

- Collect blood work (paying special attention to lipoproteins, triglycerides, glucose, and insulin among other things) and other measurements (e.g., DEXA if you want to assess body composition, waist measurement).

- Get intimately familiar with all the places sugar shows up that may seem counter-intuitive (e.g., “healthy” cereals, sauces, salad dressings, bread). To do this experiment, you need not restrict your complex carbohydrate intake, but you’ll have to substitute products without added sugar. For example, before I was in ketosis but beginning to discover my own susceptibility to sugar, I had to make my own spaghetti sauce from scratch rather than pour it out of jar. I had to make steel cut oatmeal rather than eat Quaker oats. I had to buy bread made with zero sugar (at $7 a loaf!) rather than my usual “whole wheat” bread. You get the idea. It takes time, and you should expect to spend a few extra dollars on food. But, it’s actually possible to find foods that contain minimal to zero added sugar.

- With this information in hand, begin the intervention: aim for a reduction of at least 50% from step #1. (In my first experiment I did 6 days per week of zero sugar, and one day of all I wanted. Ultimately, this became too difficult, and it actually became easier to just go zero every single day.)

- Repeat the measurements (i.e., step #2) after about three months. If you’ve seen minimal effect, assuming you were methodical and consistent, you’re probably in the Jill camp. If you’ve lost fat, seen a reduction in your triglycerides, fasting glucose and insulin levels, increased your HDL-C, and decreased your apoB or LDL-P (assuming you were able to measure them), you’re probably in the Peter camp.

Last point I’ll make, as I suspect at least some of you are wondering. How do two genetic outliers treat their genetic hybrid (i.e., our daughter)? I’ve written about this previously. In short, we limit the sugar she eats in our house, but not so much outside of the house (e.g., birthday parties). I estimate she eats about 25% of the sugar a “normal” kid does. There is no doubt she loves it, and even a week ago when we went on a daddy-daughter date, I got her ice cream with sprinkles for dessert (the irony of me carrying a bowl of sprinkle- and Oreo-covered ice cream through a crowded restaurant was not lost on me).

What does amaze me is how it seems to override her senses. That night, she had a big plate of salad, a bowl of soup, and even a large slice of pizza (if you’re wondering, I had 3 large plates of salad with chicken). She claimed to be absolutely full, and I believed it. But when I brought that ice cream out, it was like she had never seen food in her life. She simply devoured it. The best part? When she looked like she was done, I said, “OK sweetie, looks like you’re done, time to get going…” only to have her say, “No daddy! I’m still finishing the chocolate broth!” She literally left not one drop of melted ice cream (“chocolate broth”) or one single sprinkle or one single crumb of Oreo behind.

This does not seem “normal” to me, and for this reason I guess I refuse to accept, personally, that sugar is just a benign empty calorie. But, one day our daughter will have to decide for herself where she lies on the distribution and how much she cares to do anything about it. Until then, we’ll save the chocolate broth for special (and not too common) treats.

So, in response to the question, “Is sugar toxic?” it seems to me the answer is, “yes, sugar is probably chronically toxic to many people.” And so is water. And so is oxygen. My sincere hope, however, is that you now understand that this is probably the wrong question to be asking. The better question is probably “What dose of sugar can I (or my child) safely tolerate to avoid chronic toxicity?” The goal should be to figure out your toxic dose, then stay well below it. (It’s probably not wise to consume 95% of the toxic dose of APAP just because you have a really bad headache.) What makes this important, of course, is that with water and oxygen, the toxic doses are so far out of the range of what we normally consume, it’s not really necessary to expend much mental energy worrying about the toxicity. But with sugar, at least for many of us, the toxic dose is easy to consume, especially in world where sugar resides in almost everything we eat.