I was hoping to reduce the amount of time and energy I would devote to thinking about COVID-19, in favor of getting back to my preferred subject matter, but I’m not doing a great job of ignoring coronaviruses. This email is a case in point. I’ve been thinking a lot about psychological stress and how it relates to our response to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Before delving into this, I want to briefly set the stage by outlining where psychological stress fits into the bigger picture of the host response.

Broadly speaking there are two major drivers of infection by, and complications of, SARS-CoV-2: (1) pre-existing immunity and (2) host factors rendering one more, or less, susceptible to damage from the virus.

Pre-existing immunity to SARS-CoV-2 is a topic being explored actively and, should it exist, one hypothesis is that it is mediated by previous exposure to other beta coronaviruses with the potential for cross-reactivity with the coronavirus of interest today. A study published in Cell this week found memory T cells in people who had not been infected by SARS-CoV-2 which were nevertheless (in vitro) capable of recognizing the SARS-CoV-2 virus. More on this study and the idea behind memory T cells in another podcast.

Of course, the ultimate form of pre-existing immunity is that which is conferred by a vaccine, but since there are no vaccines available today, let’s just consider pre-existing immunity based on exposure to other viruses (or even vaccines to other viruses, as some have suggested). Pre-existing immunity is a continuous variable, so we can have zero pre-existing immunity, we can be fully immune, or have some incomplete level of pre-existing immunity.

There are many host factors beyond pre-existing immunity that can render some people more, or less, susceptible to damage from the virus, but broadly can be separated into two major factors, those that are resilience-mediated and those that are immune-mediated.

All things equal from an immune perspective, a 25-year-old is going to fare much better than a 75-year-old if both are infected with SARS-CoV-2, suggesting a role for resilience-mediated factors.1Age itself may just be a proxy for underlying illness. The average septuagenarian is more likely to have pre-existing illness vs someone in his 20s, but early data suggests that it’s exceptionally rare for healthy individuals to die from (or with) COVID-19, regardless of age. In NYC for example, of 10,600 deaths in people aged 65 and above where underlying condition status was known (as of data provided on May 29), only five of those individuals had no underlying conditions. Time will tell whether age is more of an effect than a cause. Resilience-mediated factors may include the number and location of ACE2 receptors, pre-existing pulmonary reserve, endothelial function, and chronic inflammatory states—such as obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Immune-related host factors can leave us with our guard down or keep it up. Exercise, for example—a physiological stressor—is related to both enhancement and diminution of the immune system, depending on the context.2There is evidence that the risk for respiratory infections increases in competitive endurance athletes during periods of intense training and competition. On the other hand, moderate exercise appears to enhance the immune system and lower the risk of infections.

But as I alluded to above, I want to expand on the role of a different kind of stress—psychological stress—something I think most of us are feeling in higher quantities than we might be accustomed to today. In fact, a JAMA letter published this week, suggests that psychological distress (and loneliness) is on the rise.

Can psychological stress—when psychological distress exceeds a person’s ability to cope—suppress resistance to infection? In a classic New England Journal of Medicine paper from 1991, Sheldon Cohen and two of his colleagues tried to answer this question by conducting the following experiment.

After completing a series of questionnaires assessing degrees of psychological stress, nearly 400 healthy subjects, aged 18 to 54 were given nasal drops containing one of five respiratory viruses—rhinovirus type 2, 9, or 14, respiratory syncytial virus, or coronavirus type 229E—in doses intended to resemble what we generally see with person-to-person transmission. An additional 26 subjects were given saline nasal drops as a placebo. Starting two days before the viral challenge and continuing through six days after the challenge, subjects were quarantined in apartments—alone or with one or two others—and monitored daily for the development of symptoms of clinical colds. Approximately 28 days after the challenge, a serum sample was collected for serologic testing. Serologic testing tells us the number of subjects who had an infection, even if asymptomatic, while the daily monitoring for clinical colds represents the number of symptomatic infections.

A psychological stress index, and scoring system—calculated and grouped into quartiles—was based on three measures: (1) the number of major stressful events in the past year, (2) the degree to which the subject perceived that current demands exceeded his or her ability to cope, and (3) an index of current negative affect.

The investigators also adjusted the data for the following standard control variables: serologic status for the experimental virus before the challenge, age, sex, education, allergic status, weight, the season, the number of subjects housed together, whether a subject housed in the same apartment was infected, and the identity of the challenge virus.

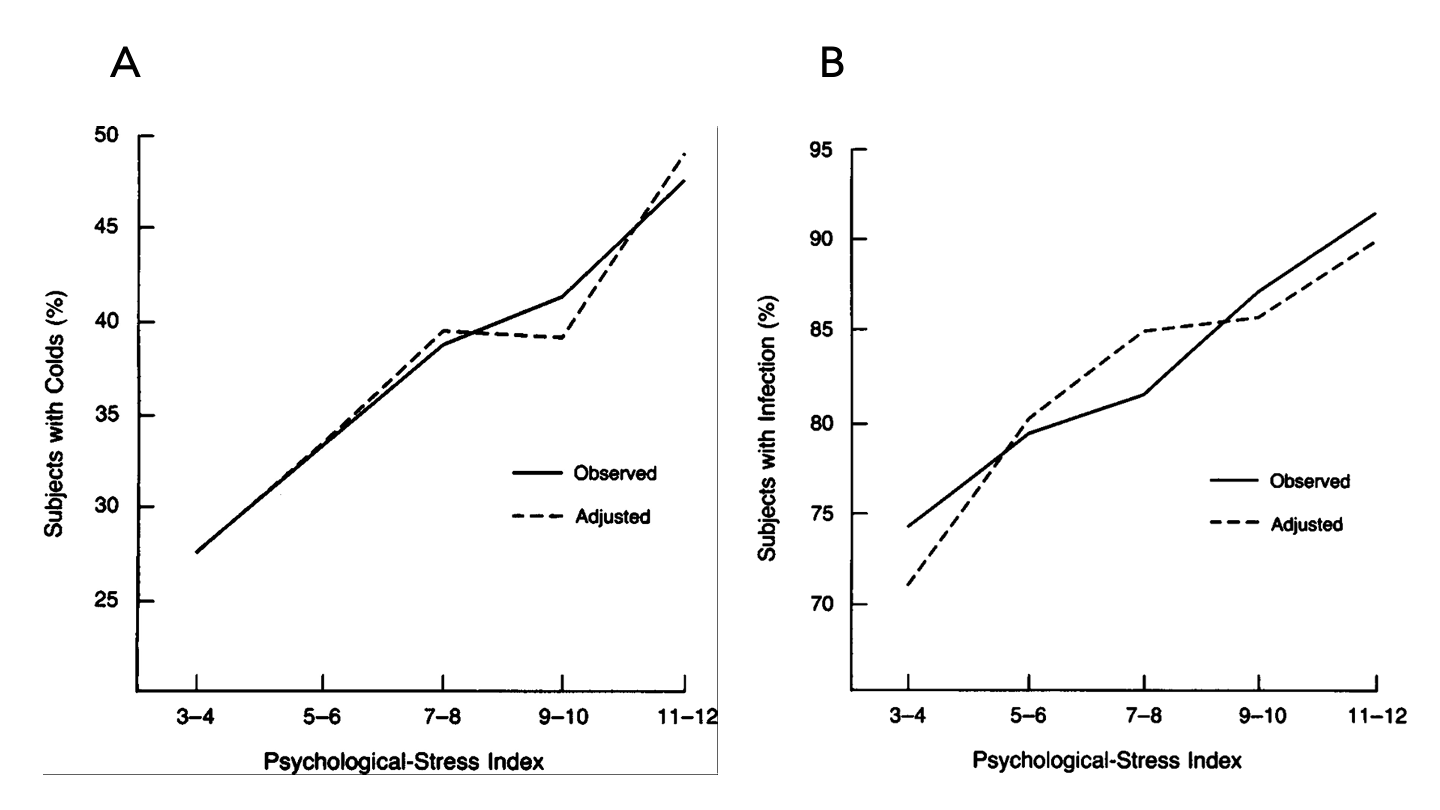

The rates of colds—which can be interpreted as the incidence of symptomatic infections—increased in a dose-response manner with increases in the stress-index score, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.98 when comparing the highest and lowest quartile groups. The rates of infection overall—symptomatic or asymptomatic—also increased in a similar fashion, with an OR of 3.45. After adjusting for confounders, ORs were 2.16 and 5.81 for the rates of colds and infections, respectively, meaning that when the investigators tried to control for variables that could bias the results, the associations became larger: higher levels of stress were associated with more than 2-fold risk of symptomatic infection, and nearly a 6-fold risk of overall infection.

For all 394 subjects exposed to a virus, the incidence of clinical colds (i.e., symptomatic infections) ranged from approximately 27 to 47 percent (shown in Figure A below), and overall infection rates from 74 to 90 percent (shown in Figure B below), according to levels of stress. In short, higher levels of stress were highly associated with more infections, overall, and more symptomatic infections (colds).

Figure. Observed association between the psychological-stress index and the rate of (A) clinical colds and (B) infections, and the association adjusted for standard control variables. Image credit: Cohen et al., 1991

What’s also interesting from this experiment is that the effects of stress were the same, directionally, for both subjects who were seropositive and seronegative (i.e., those who did and did not have pre-existing antibodies to the virus, respectively) before being challenged with a virus. While those who were seropositive had lower absolute rates of infection (as expected), the relative trends were similar to those who were seronegative. In other words, even if subjects were previously exposed to the virus, and had specific antibodies against the virus, the incidence of infections and symptomatic infections were positively associated with increased stress.

All experiments have limitations, and this study is no exception. Confounding in a study like this can often lead to results showing a signal when there’s truly only noise. Even if we assume there’s a causal relationship, it doesn’t mean low levels of stress make us immune to infection or death, nor do high levels of stress guarantee them.

Of course, replicating this study, administering nasal drops containing SARS-CoV-2 to healthy subjects would give us more specific insight into how psychological stress relates to the risk of infection and severity of outcomes, but for obvious reasons, nobody is lining up to do that study. So we try to do the best we can with incomplete information. Psychological stress may be one factor that we can try to influence. Even if the effect is small, if we can identify modifiable factors, especially in those most susceptible, instead of stacking risk, we can start to reduce it.

Pandemic or not, I believe lowering psychological stress can reduce the risk of disease, both physical and mental, and I would not be surprised if psychological stress plays an important role in dealing with SARS-CoV-2. If psychological stress is a modifiable factor, the question becomes, how do we modify it in a favorable way?

On my podcast, Sam Harris and Ryan Holiday each talked about how to practice mindfulness and stillness, respectively, and how to make them consistent. Robert Sapolsky also pointed to daily and deliberate mindfulness or meditation to reduce stress. More recently, Sam and Ryan came back on the podcast to discuss specifically how we can use these practices to help cope with stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. The other practice to help manage psychological stress is consistent physical exercise. I find myself exercising these days more for the mental benefits than the physical ones. Another important component for a number of people is talking to a mental health professional to see if there’s trauma being left untreated. Paul Conti has spoken eloquently on the ubiquity of this and how it can be overcome. Paul also returned to the podcast and addressed the stress and trauma that the COVID-19 pandemic is creating and ways to combat these problems.

There are many other factors that have an effect on how we respond to adversity. If we want to know how to protect ourselves from SARS-CoV-2, we need to understand the host response in as much detail as possible. The more reliable knowledge we can accumulate, the better we can understand this virus and how to move forward.

– Peter