I recently bought a food product that had a “no MSG” label on the front of it. This strikes me as an odd selling point—the sticker is front and center like a shiny gold star. I presume it’s meant to ensure safety and reassure the buyer. But for what? Do people really still believe that monosodium glutamate (MSG) is harmful? It turns out there is a widely held belief that MSG is bad for us.

You may have heard MSG can make you sick or have seen similar “no MSG” signs in restaurant windows and on food packaging. Yet all the research I’ve seen says otherwise. MSG is not a harmful substance. Further, The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) designated MSG as a Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) ingredient long ago in 1958. Despite requests over the years to remove the GRAS designation, the FDA kept it on the list given the available evidence. But the additive continues to be the subject of controversy, and many still question its safety. A GRAS designation does not mean that a substance does not cause any harm—just reference what I wrote regarding sweeteners and high fructose corn syrup, which I likewise talk about in AMA#18. But the controversy over the safety of MSG has been largely overblown. There’s no evidence to substantiate the claim that MSG causes ill effects in most people who consume it. A minority of people are hypersensitive to glutamate and MSG in food—added or natural—and in a study where MSG was given at 3 grams, in the absence of food, sensitive individuals had short-term, transient adverse reactions. With that said, the story I’m about to share shows how science can say one thing, but strongly held beliefs remain. But before I tell it, let’s start with a little MSG primer, and its presence in the food supply.

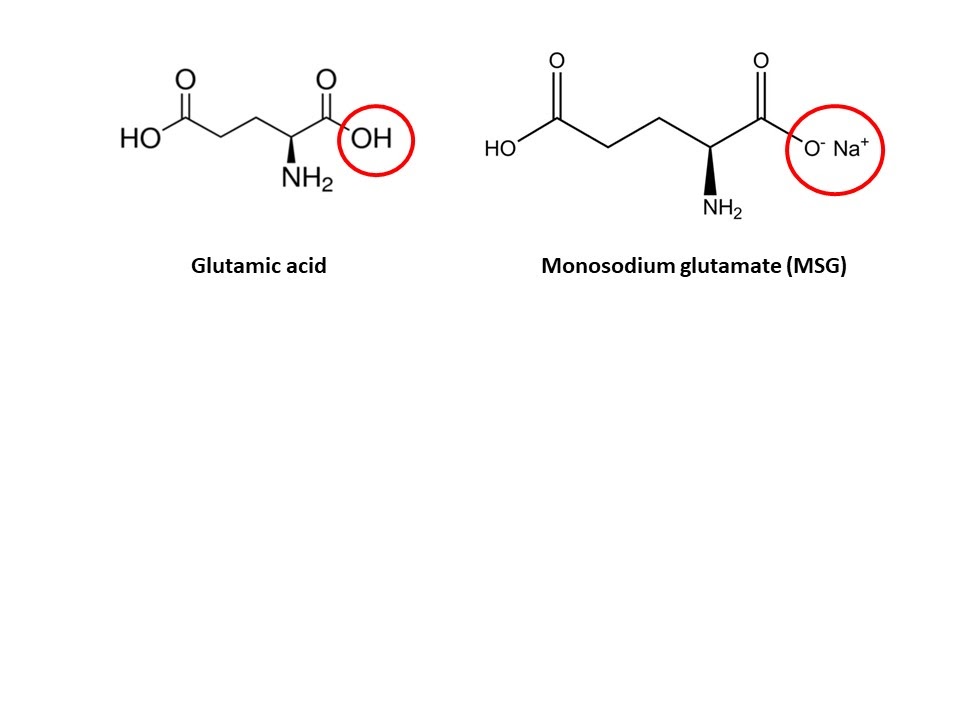

MSG is the sodium salt of an amino acid called glutamic acid. Glutamic acid is a nonessential amino acid, meaning that our bodies can produce it. It has two carboxyl groups consisting of a carbon atom, two oxygen atoms, and a hydrogen atom (COOH). When a carboxyl group loses its hydrogen atom, it becomes negatively charged (COO-) and can bond with a positively charged ion. MSG is formed when a positively charged sodium ion (Na+) binds to the negatively charged carboxyl group (COO-) (Figure).

Figure. Structures of glutamic acid and monosodium glutamate.

In 1908, a Japanese biochemist, Dr. Kikunae Ikeda, attributed the distinct taste of seaweed broth to glutamic acid. He named it umami, translated as savory. Umami is one of five basic tastes, which also include: sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. From that point on, the newly isolated glutamic acid was mass-produced and used as seasoning to enhance the flavor of food. Isolated or not, the sodium salt of glutamic acid is found naturally in foods such as tomatoes, cheese, and in vegetables like broccoli and cabbage. So the sodium salt form of glutamic acid both occurs naturally and synthetically—it makes food taste extra tasty. But how did it become the subject of warning labels and shrouded in controversy?

It’s a strange story about how public media picked up and ran with questionable information. The NPR podcast This American Life dedicated part of an episode to the account. In 1968, a Letter to the Editor warning readers about “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” (CRS) appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). You may know about CRS. Maybe you’ve experienced it yourself—the syndrome refers to the complex of symptoms, often attributed to MSG, like burning sensations in the mouth, facial pressure, headache, maybe some chest pain. And if it sort of sounds like what could happen with elevated sodium intake, think again. MSG is not high in sodium and actually allows for far less added salt given its flavor-enhancing properties. It contains one-third the amount of sodium as sodium chloride (table salt), about 12% versus 39%. The ratio means very little if more MSG is added to a given food in order to make up the difference. However, MSG in excess has been reported to lose the umami taste and make food less-palatable. Further, one study suggests that adding MSG to soup requires less sodium (note this study seems to have been unblinded).

The letter was signed by a physician and Chinese immigrant named Dr. Robert Ho Man Kwok, who claimed to feel numbness and palpitations after eating in Chinese restaurants in the US, speculated that MSG was the cause, and called for further research. Fifty years later, an elderly white orthopedic surgeon named Howard Steel claimed that he had made up the name and written the letter himself as a prank after he made a bet with a friend. However, there was an actual doctor named Robert Ho Man Kwok who at the time worked at the research institute named in the letter, and though he was dead by the time Steel made his claim, Kwok’s family maintained that he had indeed written the letter. It seems unlikely that Steel, who is also now dead, was the actual author, especially given that Kwok’s family confirmed that Kwok wrote it. Nonetheless, one of the replies to the original letter speculated that it was a joke, and regardless, it took on a life of its own thereafter.

The most practical way to determine the reaction to Kwok’s letter decades later was to dig through old print journals, and several researchers who searched found numerous reply letters in subsequent issues. They found that some letters were clearly tongue-in-cheek, and most seemed to be part of a lighthearted NEJM tradition in which letters to the editor jokingly described quotidian symptoms using excessively technical medical terminology. Though most of the response letters in NEJM were no doubt meant to be humorous, the joke was completely lost on the media, which dutifully reported on this new “health concern.” Six weeks after its publication, the New York Times ran an article on this so-called “Chinese restaurant syndrome,” including interviews with defensive Chinese restaurant owners. Several major newspapers quoted from one of the satirical response letters to the NEJM as if it were a scientific document. The article did not mention that MSG is also widely used in many foods associated with the west rather than China, such as flavored potato chips, parmesan cheese, frozen dinners, and fast food. The inconsistency—symptoms occur after eating “Chinese” restaurant food with added MSG, but not in others—further suggests the entire argument is devoid of merit.

The reporters who covered the story did not understand the difference between a letter to the editor and a peer-reviewed research article. The national news took an inside joke among physicians and presented it as scientific fact. They set the stage for decades of misunderstanding about a widely used additive, and provided an unfortunate example of what happens when science, personal anecdotes, and cultural bias collide.

However, this case allows us to observe how the scientific method can operate—confirming or refuting a hypothesis or, in this case, something held as true with nothing empirical behind it. Remember that study replicability, irrespective of conclusion, is critical for accepting what it comes to conclude. No single study and especially no group of study of the same kind (i.e., uncontrolled, observational) are sufficient. And even then, conclusions can change. After all, the easiest person to fool is ourselves.

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool. So you have to be very careful about that. After you’ve not fooled yourself, it’s easy not to fool other scientists. You just have to be honest in a conventional way after that.” — Richard Feynman

We can trace how, in the wake of the original 1968 letter to the NEJM, scientists began to look critically at MSG. The published findings have varied in degrees of rigor in experimental design and results have been inconsistent. In the late 1960s, Dr. John Olney raised the most significant concerns regarding MSG, conducting research on infant mice and found that MSG had toxic effects on the brain and it was associated with other health issues. However, the levels of MSG that he found to be toxic resulted from force feeding over a short time period, so the data’s applicability to human infants in real-life situations was unclear, and many other studies could not replicate his results. In contrast, the work of Richard Kenney found no support for the notion that MSG consistently caused specific symptoms. Kenney found that symptoms were not consistent day-to-day and did not correlate with plasma glutamate levels or other physiological markers. Other studies showed similar results. Further, the published conclusions of Mark Friedman from a symposium evaluating MSG’s purported relationship to obesity and abnormal fat metabolism found no effect on body weight and rodent MSG injection studies that reported toxic neural effects were not applicable to humans. Almost no ingested MSG passes the blood-brain barrier, meaning that dietary MSG does not gain access to the brain.

The MSG case shows how susceptible we are to confirmation bias and other cognitive biases which I have discussed in previous emails and in discussion with Dr. Carol Tavris and Dr. Elliot Aronson. In scientific research, it is why double-blind studies are so important. One study that asked about CRS and Chinese food consumption used two questionnaires: when the questionnaire did not specifically mention CRS, 3-7% reported symptoms. But when the syndrome was mentioned by name, 31% reported CRS symptoms. The list of published studies evaluating MSG-related symptoms goes on and on. However, a 30,000-foot view shows that decades of research demonstrated no danger from MSG consumption. Many separate scientific reviews—by the Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Health Organization (WHO) from 1987, the European Communities’ Scientific Committee for Foods in 1991, and the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB) from 1995—all concluded that concentrations of MSG in food are not hazardous to human health. As mentioned, the latter showed safety for the general public, but suggested that a small percent of the population may have adverse effects from large quantities of MSG in the realm of 3 grams. For reference, the average daily intake of added MSG in the U.S. is about 0.55 grams. A 2006 review of 40 years of data concluded that clinical trials have failed to identify a consistent relationship between the consumption of MSG symptoms associated with the so-called CRS. Similarly, a 2009 review noted the lack of a consistent relationship between MSG ingestion and clinical effects.

We can learn a lot from the MSG myth that continues to persist. This story shows it’s very difficult to dispel longstanding cultural myths, even when scientific evidence dismantles them. As MSG researcher Robert Kenney told the Washington Post, “No amount of evidence will ever get rid of an anecdote.” Or as Jonathan Swift, the 17th century satirist and author of Gulliver’s Travels, said, “A lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is still putting on its shoes.”

—Peter