You’ve likely heard the term “standard drink” when describing alcohol consumption: a can of beer, a glass of wine, and a shot of liquor each have about the same amount of alcohol, 14 g. But when it comes to alcohol’s effects on the body, a “standard drink” has very different implications for men vs. women, a point which is reflected in alcohol consumption guidelines. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines heavy drinking for men as >14 drinks per week or >4 drinks per day. For women, however, heavy drinking is defined by much lower consumption levels: only >7 drinks per week (or >3 drinks per day).

As I mentioned in a recent Ask Me Anything episode, at first glance this large discrepancy makes no sense – the number of weekly drinks for women is half that of men. It’s true that the average woman is smaller than the average man by height and weight, and in a larger person, the same volume of alcohol will be more systemically diluted (which is also why scientific studies dose alcohol based on subject body weight). Still, the average woman certainly isn’t half the size of the average man. In terms of body weight, women weigh on average about 15% less than men. So a 50% difference in alcohol consumption recommendations seems overly conservative for women (or maybe overly generous for men).

So what might explain this large discrepancy in the guidelines?

It turns out that body weight alone cannot tell the full story. Alcohol dissolves much more readily in water than in fat, making total body water content a more relevant measure than body weight for predicting how a given quantity of alcohol will impact an individual’s BAC. If alcohol can be diluted in a larger water volume, BAC won’t rise as high as it would in a smaller volume. Total body water content is more closely related to body composition than to body weight (for example, lean mass is associated with more water than fat mass) and is a function of age, height, weight, and sex.

Men, on average, have greater body water content than women, resulting in a lower rise in BAC for a given quantity of alcohol. A 40-year-old American man in the 50th percentile for height and weight (5’9”, 200 lbs) has about 42% more body water than an American woman at the 50th percentile (5’4”, 166 lbs) of the same age (47.8 L compared to 33.7 L). For one standard drink, assuming complete alcohol absorption in both individuals, this will result in a BAC of 0.029 for the man but a BAC of 0.042 for the woman. Even when matched for height and weight, most women have a lower total body water volume than men because women generally have a higher body fat percentage. This means that for a man and woman of equal height and weight, the same amount of alcohol is concentrated in a smaller volume in a woman, leading to higher blood alcohol levels. Let’s return to our example of the 5’9”, 200-lb man, who has an estimated 47.8 L body water. A 5’9”, 200-lb woman, in contrast, has only about 38.8 L of total body water, corresponding to a BAC of 0.036 for one standard drink – 24% higher than for a man of the exact same height and weight!

What about alcohol metabolism?

I’m afraid the bad news doesn’t end with discrepancies in body size and composition: differences in alcohol metabolism further exacerbate the impact of alcohol on women vs. men. After consumption, alcohol is eventually broken down by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), primarily in the liver. However, this enzyme is also found in the stomach, where it can catalyze first-pass alcohol metabolism, thus limiting the amount of alcohol that can be absorbed from the intestine, enter circulation, and make its way to the liver. The amount of gastric ADH is significantly lower in women than in men. The reduced level of gastric ADH means that less alcohol is metabolized in the stomach, resulting in greater absorption and a larger quantity of alcohol entering circulation. This constitutes another reason why, even when alcohol dosage is adjusted for body weight, BAC will be higher in women.

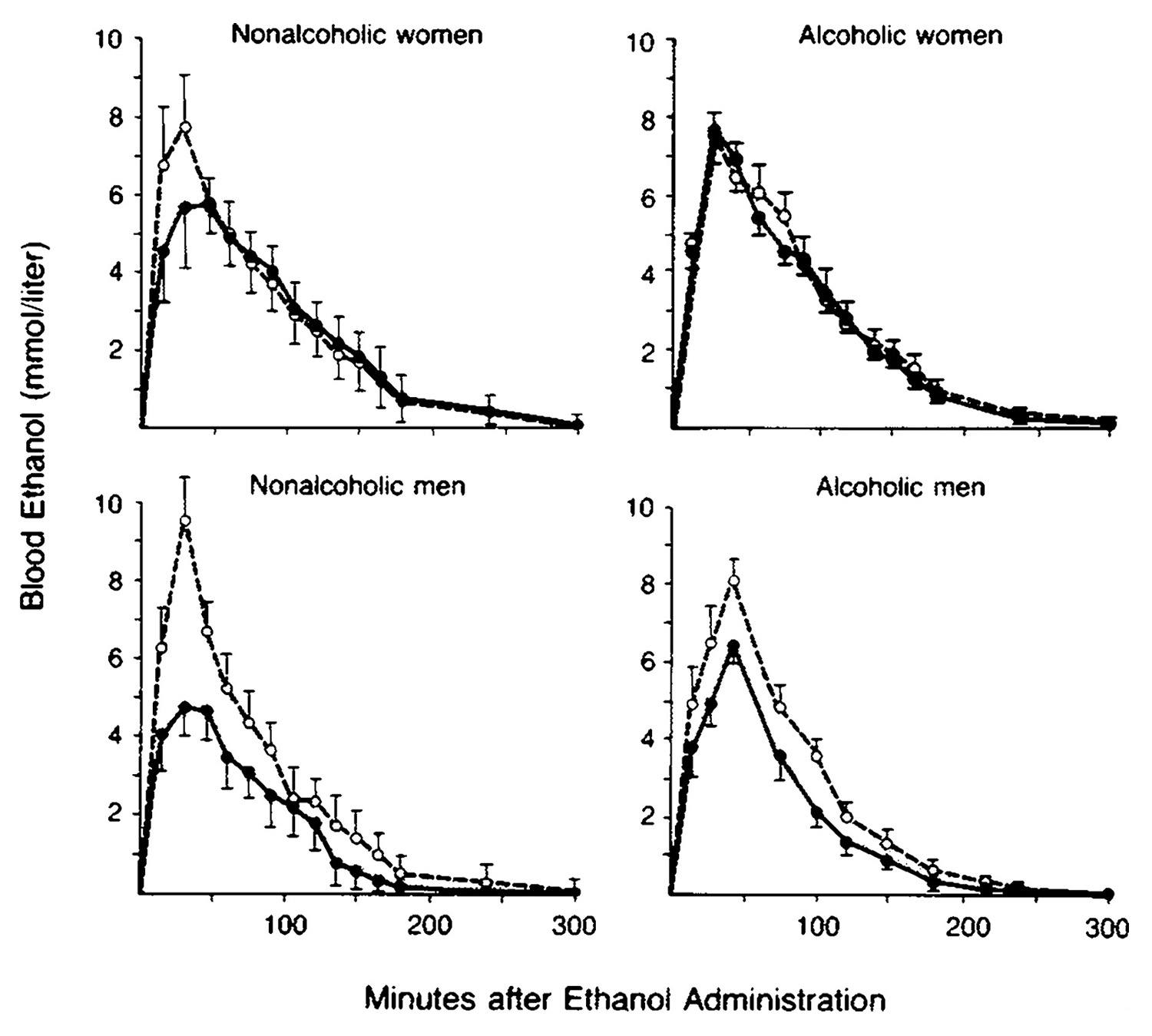

The importance of this first-pass metabolism in the stomach is demonstrated by studies comparing intravenous (i.v.) vs. oral alcohol consumption. When alcohol is administered i.v., metabolism in the stomach is bypassed, allowing us to quantify the degree to which gastric ADH contributes to alcohol metabolism. For women, the absolute difference in peak BAC from i.v. administration compared to oral consumption is relatively small compared to the difference observed in men, revealing that gastric ADH is a far more active contributor to alcohol metabolism in men than in women.

Fig. Effects of Sex and Chronic Alcohol Abuse on Blood Ethanol Concentrations. Alcohol was administered orally (solid lines) or i.v. (dashed lines) in a dose of 0.3 g per kg of body weight. The shaded area represents the difference between the curves for the two routes of administration (the first-pass metabolism). [Frezza 1990]

What are the practical implications?

In the short term, women will be more likely to experience the effects of intoxication when drinking the same volume of alcohol as men and will have a higher BAC, increasing the risk for intoxication-related injuries, fatalities, and legal repercussions (e.g., driving while intoxicated). In the longer term, increased alcohol consumption leads to increased risk for myriad diseases including alcoholic fatty liver disease, alcoholic gastritis, hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, and alcoholic cardiomyopathy. There have also been observed monotonic relationships with colorectal and other cancers and neurodegenerative pathologies, meaning that the risk of developing these diseases increases proportionally with increasing amounts of alcohol reaching these tissues. Since higher BACs mean that more alcohol reaches tissues throughout the body, women’s susceptibility to high BACs may put them at particular risk.

As I’ve discussed in the past, regular alcohol consumption at virtually any level is likely to have negative effects on health, but are alcohol consumption guidelines overly conservative for women vs. men? Their average smaller size, higher percent body fat, and reduced first-pass metabolism mean that women may be at far greater risk of the health consequences of alcohol and need to exercise even more caution around alcohol consumption than men. Although women are not half the size of men, when we take all factors into consideration, the recommendations for 50% fewer weekly drinks might not be so far off after all.