Excess alcohol consumption is widely accepted to cause an increase in cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. However, there has been some debate as to whether low to moderate alcohol intake is actually beneficial to cardiovascular health, as has been reported in past studies. Individuals who consume low and moderate levels of alcohol have been shown in observational studies to have characteristics associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk, yet many have argued that this apparent benefit of alcohol is really the result of other lifestyle factors that covary with low or moderate alcohol consumption and are themselves related to better health. While observational studies often attempt to adjust for some of these factors, no study can ever correct for every possible relevant variable, leaving the door open for misleading effects from confounders.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) allow more control over confounding variables associated with alcohol consumption, but these trials are difficult to conduct for alcohol consumption. First, the effects of low and moderate alcohol intake compared to abstinence on cardiovascular disease risk may be small enough that they would take many years to demonstrate significant divergence between groups, requiring decades-long studies which would be prohibitively expensive. Second, RCTs studying alcohol use would likely broach significant ethical concerns, given the health risks associated with alcohol consumption. With unreliable observational data and insurmountable logistical challenges to RCTs, what can we believe regarding the relationship between low or moderate alcohol intake and CVD risk? A study published last year in JAMA Cardiology addressed this question with the elegant solution of Mendelian randomization.

What is Mendelian randomization?

Mendelian randomization (MR) is a method used to overcome the pitfalls of observational research, including the effect of confounding variables, to better allow causal inference without conducting an RCT. MR uses gene variants that are linked to a given exposure (in this case, alcohol consumption) as a proxy measure for that exposure. Gene variants are randomly distributed in the population, so using these variants in the place of alcohol consumption essentially constitutes a “natural” randomized trial and eliminates confounding due to other lifestyle or environmental factors. (More details on MR methodology can be found here in an excellent review.)

About the Study

The study by Biddinger et al. employed MR to assess the relationship between alcohol intake and cardiovascular disease risk. The investigators used data from 371,436 individuals from the UK Biobank, and followed these individuals over a ten-year period to determine future CVD incidence. CVD outcomes assessed included hypertension, coronary artery disease (CAD, defined as self-reported or registered hospitalization/death for myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting or angioplasty, or triple heart bypass), myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation.

The genetic proxy used in the MR for this analysis utilized nine gene variants associated with alcohol use disorder. Several of these, including variants in ALDH1B and ALDH1C (alcohol dehydrogenase 1B and 1C), directly impact the processing of alcohol and thus affect alcohol consumption by altering the magnitude of aversive side effects, while others, such as variants in DRD2 (dopamine receptor 2), are associated with the behavioral pathways implicated in alcohol addiction. The authors conducted statistical tests to ensure that necessary assumptions for MR were met – for instance, by determining that the genetic variants were not themselves related to CVD independently of alcohol use. Likewise, they confirmed that the variants used were indeed associated with alcohol exposure by monitoring levels of gamma glutamyl transferase, a blood-based biomarker for alcohol use, and by collecting self-reported alcohol intake data. Alcohol intake levels were stratified as light (>0-8.4 drinks/week), moderate (>8.4-15.4 drinks/week), heavy (>15.4-24.5 drinks/week), and abusive (>24.5 drinks/week).

What did the study find?

In contrast to the findings of many earlier observational studies, Biddinger et al. found that all levels of alcohol exposure were associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease. In a linear analysis of the relationship, the authors observed that each standard deviation increase in genetically predicted alcohol consumption was associated with a 30% higher risk of hypertension (OR=1.3; 95% CI: 1.2-1.4; P<0.001) over the ten-year follow-up, and a 40% higher risk of CAD (OR=1.4; 95% CI: 1.1-1.8; P=0.006). (The trend toward increased risk persisted for MI, stroke, and heart failure, but these did not reach statistical significance.) Even among the light drinking group, every one-drink per day increase in alcohol consumption was found to significantly raise risk of hypertension by 30% (OR=1.3; 95%CI: 1.1-1.5; P=0.003) and CAD by 70% (OR=1.7; 95%CI: 1.2-2.4; P<0.001). These results seem to refute the theory that low levels of alcohol consumption are beneficial for cardiovascular health and demonstrate that quite the opposite is true – even low intake is detrimental.

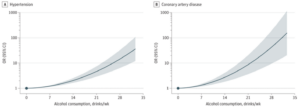

But the story didn’t end there. The authors next conducted tests for nonlinearity in the relationship between alcohol use and CVD risk and discovered that increases in intake did not affect the risk equally across drinking groups (light, moderate, heavy, and abusive). Specifically, while every one-drink per day increase in alcohol consumption among light drinkers increased the odds of hypertension and CAD respectively by 30% and 70% as described above, the same incremental increase in genetically predicted consumption raises the odds of hypertension and CAD in moderate drinkers by 70% and 80%, respectively. In the abusive drinking group (>24.5 drinks/week), a one-drink daily increase elevated hypertension risk by 160% (OR=2.6; 95% CI: 1.6-4.2; P<0.001) and CAD risk by a whopping 470% (OR=5.7; 95% CI: 2.4-13.5; P<0.001). The continuous representation of this relationship is shown in the figure below, which clearly demonstrates how CVD risk increases monotonically and not linearly but exponentially with progressive levels of alcohol consumption.

Implications for Health

Contrary to many epidemiological studies, Biddinger et al.’s results indicate that no level of alcohol intake – however small – is good for cardiovascular health, but the nonlinearity of the relationship between genetically determined drinking level and CVD risk has two important implications. Firstly, it tells us that people who consume alcohol at low levels indeed have elevated CVD risk relative to abstainers, but that this increase is fairly small and may be mitigated or offset by other factors, as we will discuss in greater detail in an upcoming premium newsletter. Secondly, the fact that risk increases exponentially with progressively greater alcohol consumption means that the inverse is also true: risk decreases exponentially with progressively lower alcohol consumption.

This second observation may seem obvious, but it ought to be encouraging to anyone hoping to cut back on alcohol intake because it indicates that meaningful reduction in CVD risk does not require complete abstinence from alcohol. For those who drink heavily, even small reductions in intake can have enormous effects in lessening risk of hypertension and CAD. For instance, according to Biddinger et al.’s results, a person who drinks, say, three glasses of wine per day (21 drinks per week) can reduce their CAD risk by over two-thirds just by shifting to two glasses per day (14 drinks per week) – a change that seems trivial in comparison to cutting out alcohol altogether, which many find difficult or even impossible.

So overall, the findings from this study offer a note of caution and a note of encouragement. Although no level of alcohol consumption is good for cardiovascular health, the risks at low levels of intake are small, and the benefits of reducing intake by even a modest amount can be substantial.

For a list of all previous weekly emails, click here.