Humans have the ability to recognize each other by our distinctive faces. But just how unique are our looks? The world population has recently surpassed 8 billion people, and with a finite number of variables defining facial appearance, it seems probable that two unrelated individuals could appear remarkably similar – in essence, “unrelated twins.”

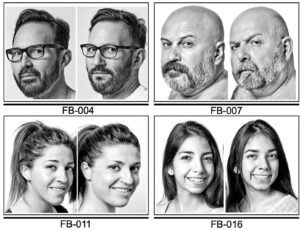

Demonstrating exactly this, in 1999 a Canadian artist started a photography project, collecting photographs of unrelated “look-alike” pairs (examples shown in figure below). Even though these sets of “twins” are not related, their uncanny resemblance sparked researchers to investigate whether the apparent physical resemblance was reflected in genetic resemblance. Since human determination of facial similarity is relatively subjective, a recent study by Joshi et al. ran photographs of 32 of these doppelgänger pairs through three facial recognition software packages. Afterward, the investigators compared the genetics, epigenetics (factors which impact gene expression independently of DNA sequence), and microbiomes of these pairs and characterized their habits and behavior through surveys. If highly similar facial features are indicative that two people have more genetic overlap than two random people, could there be more overlap than just appearances?

Figure: Examples of unrelated look-alike pairs included in the study by Joshi et al.

What did the study find?

Each of the three facial recognition algorithms provided a score between zero and one as a metric of similarity, where zero is two completely different people and one is the same image. Different methods of facial recognition will yield varying similarity metrics, but the pattern of scores was expected to be similar in unrelated look-alikes pairs. Cluster analysis, a statistical method of classifying the pairs into groups by their similarities, determined that sixteen of the thirty two pairs were clustered by all three facial recognition methods. These sixteen pairs were the main subjects of further genetic and behavioral analysis. As controls, the investigators also ran facial recognition on a database of headshots of monozygotic (identical) twins. The look-alike pairs had significantly higher similarity scores than random non-look-alike pairs across all of the facial recognition analyses, but yielded lower similarity scores than monozygotic twins for two of the three algorithms.

The human genome is made up of approximately 3 billion DNA base pairs, but 99.9% of this DNA sequence is identical across all humans. The remaining 0.1% accounts for all phenotypic variation across our entire species, and 90% of this variation appears in the form of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) – commonly-occurring differences in a single DNA base at a specific genomic position. Each individual has an estimated 4-5 million SNPs, and how closely related you are to another person is associated with the number of SNPs you share. For example, siblings share between 84-87% of SNPs, but more extended relatives, such as first cousins, share 75-77% of SNPs.

In this study, SNP arrays were used to analyze saliva DNA from each of the look-alike pairs to interrogate more than 4.3 million genetic variants, scanning for SNP positions with an intra-pair shared genotype. Nine of the sixteen triple-matched look-alike pairs were matched in more than 19,000 SNP positions associated with 3730 genes, and these nine pairs were deemed “ultra-look-alikes.” Unsurprisingly, included in the SNPs shared by “ultra-look-alike” pairs were those related to 1794 “face genes.” These face genes corresponded to 84 traits related to physical features such as lip and forehead morphology, eye color, and balding measurement, which could explain the facial similarities in two unrelated people. But what about genes unrelated to physical appearance?

Other similarities between look-alike pairs

Prior research has investigated how much of who we are is determined by our genes compared to our environment. One of the most famous was the Minnesota Twin study, which looked at monozygotic twins raised together or apart and compared measurable factors like IQ (70% based on genetics) and more subjective aspects such as personality traits (15-55% based on genetics). Knowing that at least some of who we are outside of our external appearance is based in our DNA, Joshi et al. wanted to know if other physical or behavioral similarities existed between the look-alike pairs, especially since >1900 of the identified genes were not “face genes.”

The pairs were found to have no notable similarity in their microbiome or epigenetics, as measured DNA methylation patterns. But the likeness between intra-pair individuals did extend to some variables measured through biometric and lifestyle questionnaires. That is, the look-alike pairs were more similar to each other in height, weight, education level, and smoking status than they were to other individuals in the study.

However, even though pairs showed more collective similarity to each other, many of the queried habitual behaviors, such as alcohol consumption, are also heavily affected by a person’s culture and environment. It’s critical to note that the look-alike pairs were often from the same country/city/region, which is how they found each other to submit photos to the photography project in the first place. This presents an enormous confound to lifestyle and health status findings, as any individual – look-alike or otherwise – is likely to bear greater similarity in habits and lifestyle to another person from their own country or city than they would to someone from a different environment. Further, even traits determined in large part by genetics – such as height – are likely more similar across individuals in a localized region due to the fact that people tend to be more closely related genetically to others in their own country. The results of this study therefore give us no compelling reason to believe that we can tell anything about a person’s personality, intelligence, lifestyle, or health simply by looking at their face.

Other reasons to stay skeptical

This study was conducted in a predominantly white population of European descent. Of the sixteen pairs matched by all three facial recognition algorithms, thirteen were white, one was Hispanic, one was East Asian, and one was Central-South Asian. In addition to the lack of diversity of the population itself, the facial recognition analysis was performed on black and white headshots. This potentially limits the applicability of the results across races since black and white photographs don’t show subtle differences in skin tone nor do they capture the differences in three-dimensional facial contours. The study would have been strengthened if the authors had repeated their analysis with color headshots and had the same outcomes. To have more generalizable results, future studies will need to utilize a population with greater racial diversity, particularly one including more individuals of African descent, as African populations are known to have by far the greatest degree of genetic variation and lowest correlation between neighboring polymorphisms of all ethnic groups.

Since the very small sample size of this study was identified from a curated photography project aimed at collecting pairs of look-alikes, it would also be interesting to see if the methodology works in reverse. Would unrelated pairs who have genotypically identical SNPs identified in “face genes” also be identified as “twins” by facial recognition software? The prevalence of at-home DNA testing would make it possible to find more geographically disparate pairs who look alike, which would elucidate if some of the behavioral similarities between pairs is related to genetic and not environmental overlap.

The bottom line

By the numbers, there may be someone out there who could pass for your twin. This study by Joshi et al. validates what we would already expect from our current understanding of genetics: that similarities in phenotype are at least partially mirrored in similarities in genotype. But while you may share more of your appearance-related DNA with your doppelgänger than you would with a random person off the street, don’t assume the physical resemblance reflects any increased likelihood of similar intelligence or lifestyle. Any other similarities in behavior or personality are likely due to similarities in your environment or by chance. Appearances are just that – appearances. So as the old adage says: never judge a book by its cover.

For a list of all previous weekly emails, click here.