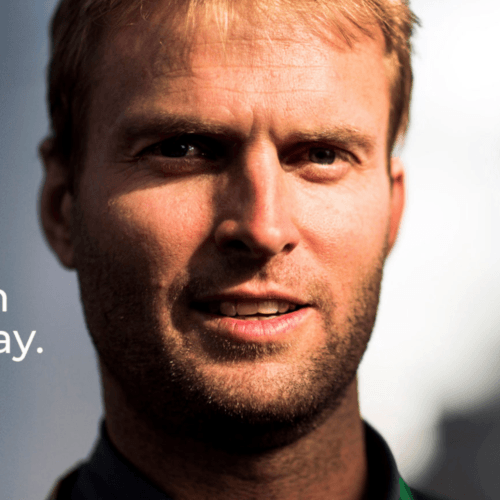

In this episode, Luke Bennett, Medical and Sports Performance Director for Hintsa Performance, explains the ins and outs of Formula 1 with a focus on the behind-the-scenes human element, and what makes it so emotionally, cognitively, and physically demanding for the drivers as well as the many team members. Luke first talks about his fascinating background with the Royal Flying Doctor Service in Australia which lead to his current position with Hintsa working closely with F1 drivers to improve their health and performance despite jet-lag and sleep constraints due to an unrivaled travel schedule. Luke also sheds light on the underappreciated level of sheer physical strength and endurance it takes to drive an F1 car combined with the extreme cognitive aptitude, spatial awareness, and ability to navigate a socially complex environment that is needed to be successful as a driver. Additionally, Luke gives an overview of how the F1 season and races work, the incredible advances in car technology and safety measures, and what Luke and Hintsa hope to bring in the near future to the unique and special sport that is Formula 1.

Subscribe on: APPLE PODCASTS | RSS | GOOGLE | OVERCAST | STITCHER

We discuss:

- What it’s like to be a “flying doctor” in Australia, and how Luke ended up working in Formula 1 with Hintsa [3:10];

- Behind the scenes of Formula 1—crazy travel, jet lag, massive teams, and fascinating human storylines [10:45];

- The incredible physical strength and cognitive aptitude needed to be a F1 driver [19:00];

- The technological leap to hybrid electric engines [29:30];

- The trend towards younger drivers in F1 [32:30];

- Advancements in safety—the history and recent upgrades [36:00];

- How Hintsa manages the athletes through the incredible social complexity of the sport [41:45];

- Explaining the difference between F1, F2, F3, and F4, and the path to reaching the F1 [47:30];

- Comparing F1 in the 60s & 70s to today—Incidences of deaths, number of crashes, physicality of driving, new regulations, and more [53:45];

- Women in F1—Past, present, and future [1:06:10];

- How F1 teams manage their cars and engine over the season, & some new regulations coming in 2021 [1:09:15];

- What insights has Luke taken from his time as a triathlete to working with F1 drivers? [1:12:50];

- How Luke survived cancer, and gained an increased sense of empathy [1:15:45];

- How Luke manages his health against the brutal travel and lifestyle that comes with working in Formula 1 [1:19:40];

- New training techniques, technology to monitor the physiology of drivers, and other things Luke is hoping to bring to Formula 1 [1:22:40];

- How long does it take a driver to learn a new circuit? [1:27:45];

- The incredible emotional control needed to be a successful F1 driver [1:30:00];

- Which F1 teams are showing signs of competing in future seasons? [1:32:15]; and

- More.

Luke Bennett, M.D.

Luke is the Medical and Sports Performance Director for Hintsa Performance, a company focused on human well-being and athletic performance with a particular emphasis in motor sport. Luke received his medical degree as well as his master’s degree in sports medicine at the University of Queensland. He then spent seven years training in intensive care before working for six years in Remote Emergency Aeromedical Retrieval with the Royal Flying Doctor Service of Western Australia.

As an ardent fan of eff-one for over 50+ years this was enthralling post for me in terms of its insight, your passion and above all else your medical twist.

Adding to something I’ve loved and involved myself with since my pre-teen years as an overlay to the longevity medical work you do that is paramount to my cancer, diabetes and health sports struggles I endure have very special meaning to me as a person, scientist and health advocate.

At 64 you in short assist me to push my whole being in living longer – I could only hope (although I believe very strongly that hope is not a strategy) for you to engage me in some form of patient capacity, or converse in some form or another.

Keep up the science and I will look after my body as it’s the only place to live right now.

“I can set the sails and steer the boat – but have no controls over the wind or waves”.

Really enjoy the podcast.

As someone who has considerable experience racing single-seaters, I’d like to offer a forceful rejoinder against increasing physiological measurements of the F1 driver, such as HRV, during the season. The alternative hypothesis you’re attempting to demonstrate would correlate stress/fatigue to an increased incidence of a mistake and/or injury. What would you do with this information if proved valid? I think this is the question to be answered, because without a valid answer it would be pointless to collect measurements. Would a driver be forced to sit out a race if biological markers of fatigue/illness/stress crossed a threshold? These guys are going to consistently struggle with HRV and markers of stress and fatigue as they deal with the pressures and demands of F1 – that’s part of the allure to the fans. The driver certainly doesn’t need the added pressure of knowing that his biological markers are being consistently monitored and that he might lose his seat if his HRV or cortisol level or insulin marker is out of whack. In my opinion, this would pose a greater risk to safety than the gain realized from increased biological awareness of one’s variability. If you’re looking for a correlation here’s the optimal one: a marginal increase in a driver’s doubt to perform drives an exponential increase in the risk he poses to himself and others.

You say that racing is the hardest thing you’ve done and that it’s impossible to convey its experience to one that hasn’t had it – that is true. But, there’s a large gap from high level amateur to pro, especially in high performance single-seaters. Amateurs struggle to reach the next level because they can’t perform to the car’s true capability. They make a mistake because they underperform the car, so the next time they get to that corner the underperformance is greater and car punishes you for not demanding more – and begins the downward circle (hence the increase in doubt that correlates to deleterious performance). I say this because you can’t analyze F1 drivers from the perspective of your experience. These drivers are unconscious competent and can perform at the highest levels for 90 minutes under almost any circumstance. I’ve raced with food poisoning, jet lag, high stress, etc… But I’ve never doubted my ability to perform when in the car – everything else fades away. The doubt is the most dangerous enemy to combat. My brake release and ability to rotate the car will be the same under every condition I face. An F1 driver is under intense stress in the car itself, and can instantly modulate inputs to compensate for under/oversteer, changing track conditions, tire wear, fuel loads, diff settings, brake bias etc… Their expertise demands freedom from certain restrictions.

I can plainly see why the driver does not want this.