In April I was part of a panel at the Milken Global Conference, the title of which was something like, “Keys to a healthier and more prosperous society.” The panel was moderated by Michael Milken, and it was great to meet him and his rock-star staff (especially Shawn Simmons, Paul Irving, and Nancy Ozeas). The other panel members were seasoned vets of the obesity discussion: Troy Brennan (Executive VP and Chief Medical Officer of CVS Caremark), Tom Frieden (Director of the CDC), Lynn Goldman (Dean of the School of Public Health at the Milken School of Public Health, at George Washington University), and Dean Ornish (president and founder of the Preventive Medicine Research Institute). I was the pauper in the group—no big credentials and zip-zero “panel” experience.

A few weeks before panel, we all jumped on a conference call and Michael set the stage for the discussion he wanted to moderate. He pulled no punches. “If you include the indirect cost—lost productivity, for example—the total cost of obesity and its related diseases is $1 trillion per year to our economy. This is unacceptable.”

Who could disagree? Hell, I usually only reference the direct cost of obesity and its related diseases—about $400 billion annually. But whether we talk about the direct or indirect cost of these diseases, I’ve always found the human cost even greater—every day 4,000 Americans die from four diseases exacerbated by obesity and type 2 diabetes: heart disease, stroke, cancer, and Alzheimer’s disease. Now that is really un-effing-acceptable.

So, back to the panel. The idea of being on a panel kind of freaked me out, even more than the sheer terror and vulnerability of TEDMed. No control. The possible need to be defensive. Sound bites over substance.

I don’t enjoy debates. Nothing comes of them. Just greater and greater polarization. The “winner” isn’t even necessarily the one with the best “facts.” Gary Taubes shared this quote with me recently, which I find really insightful. Dallas Willard, a well-known ecumenical pastor and theologian, was often invited to debate the existence of God and other matters. These invitations included Richard Dawkins himself. His response: “I don’t debate, but I am glad to enter into a joint inquiry. We will seek the truth together.” That’s the attitude I like.

In the end, I decided to just tell a few (in some cases provocative) stories. Why? Because it’s easy to present reams of data, yet so few people remember the point. (If you want to read an amazing paper on the importance of storytelling, check out this one by one of my former surgical mentors, Curt Tribble. You don’t need to care one iota about training cardiac surgeons to realize the gems in this piece.)

I realized going into this that I would be the contrarian in the group. I don’t claim to know all (or even many) of the answers, but I’m willing to bend over backwards in search of them. I realize folks (from readers of blogs to members of the audience at the Milken Global Conference) want facts, answers, prescriptions. I think we need to know more, first.

Below are the notes I made for myself in the days leading up to the panel. Basically, I wanted to tell a few stories, plus summarize it all (if given the chance). I didn’t actually “practice” this or even take notes up on stage (which I regretted when I realized everyone else was smart enough to bring notes), so if you decide to watch the actual video of the panel, you’ll note that I only vaguely followed what’s written below.

But in my mind, here’s how I thought about it. (I haven’t watched the video and I’ve pretty much forgotten anything I said, but I’m sure what’s written below is better than anything I said. I did send the video to two of the best speakers I know to get their feedback. Their feedback: could have been much better, but not the worst job ever. Lots of work to do for next time. Duly noted.)

How did I find myself interested in this problem?

My arrival at this place is really a coming together of two revelations. First, during my surgical residency at Johns Hopkins, not surprisingly, I was often dealing with the complications from diabetes and obesity in my patients. It slowly became obvious that all I was doing was slapping on the surgical equivalent of Band-Aids without ever addressing the underlying problem. I was treating symptoms and not the actual disease. When I would amputate the leg of a diabetic patient, which I had to do, regrettably, all too often, I knew that my patient was more than likely to be dead within five years anyway.

The second revelation was five years ago—September 8, 2009—to be exact. I remember it so clearly. My sport of choice was marathon swimming, and I followed what I believed to be the iconic healthy athlete’s diet. I had just completed an especially difficult swim into the current from Los Angeles to Catalina Island, becoming one of a dozen people to do that swim in both directions. After more than 14 hours in the water, I got on the boat to begin the long ride back to Long Beach Harbor, and my wife looked at me, in my speedo, 40 pounds heavier than I am today, and said, “Honey, you’re a wonderful swimmer. But you need to work on being a bit less not thin.”

And not only was I, well, fat, despite all this maniacal exercise, but it turns out I was also pre-diabetic.

Her comment launched me into a series of nutritional self-experiments. I was already working out three to four hours a day, so the problem couldn’t be sedentary behavior. It had to be what I ate. Over the next year I manipulated my diet until I found what worked for me, which paradoxically didn’t involve eating less, just eating very different from the food pyramid. Along the way I became obsessed with reading the nutrition literature. What I learned was that the evidence supporting our dietary guidelines was ambiguous, at best, and occasionally contradictory. There was a real dearth of evidence to support what seemed like the obvious questions.

I realized then, that if the guidelines didn’t work for me and if I can’t figure this out, with my background as a doctor and someone who studies healthcare, maybe they don’t work for a lot of people. Maybe there are systemic problems here. Maybe these problems were at the root of the ongoing epidemics of obesity and diabetes. Lots of maybes…and not a whole lot of clear, solid, unequivocal answers.

Since then, I’ve made a personal and professional commitment to finding the answers. And if the studies don’t exist to give us unambiguous evidence, then raising the funds and enlisting the researchers necessary to do those studies.

What does success in public health look like?

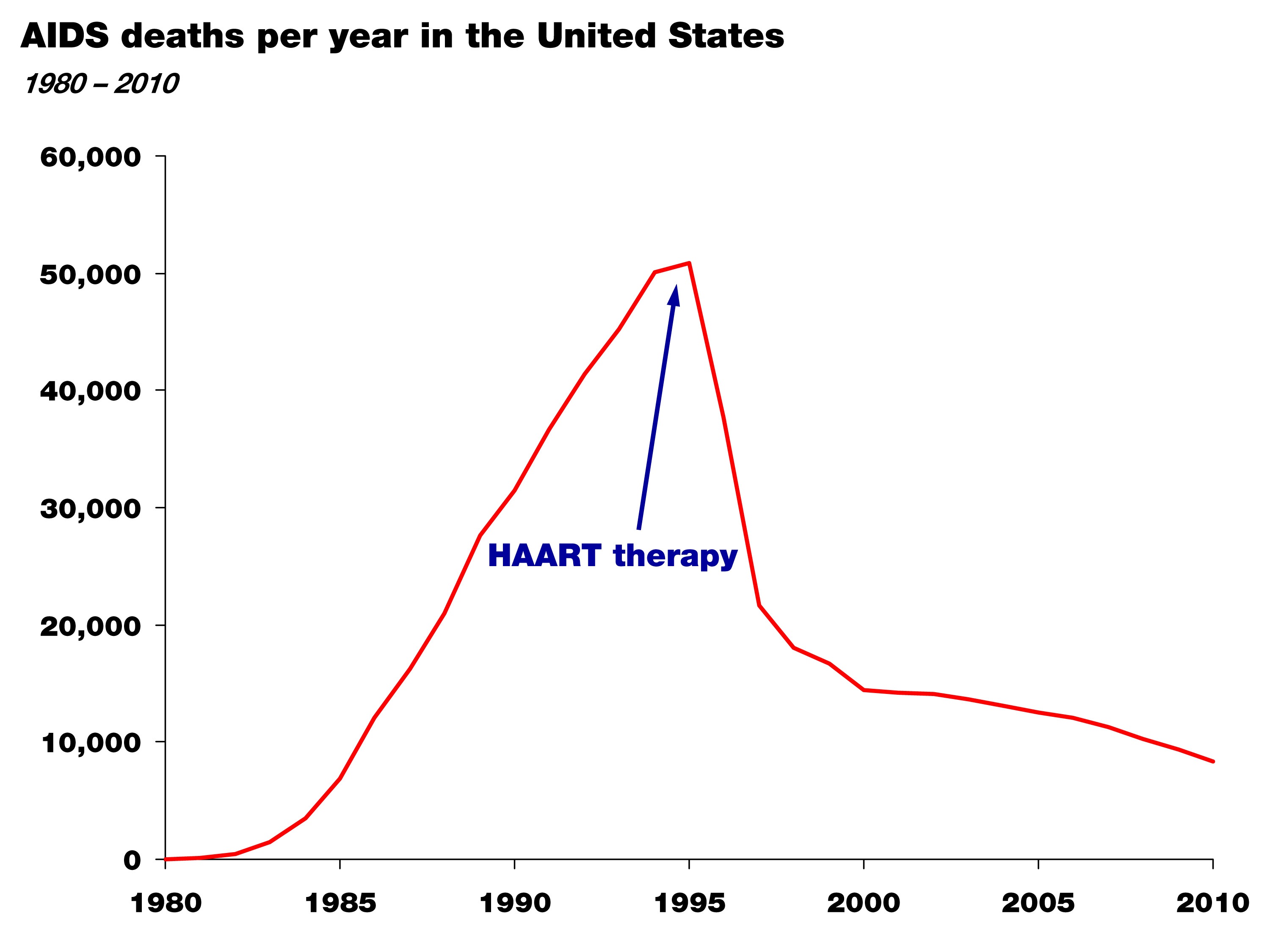

When trying to understand complex problems, I like to start with success stories, identify patterns and work backwards—reverse engineering success. Consider the following graph.

It shows the death rate from AIDS in the United States between 1981 and 2010. The point of this graph isn’t subtle. Death from AIDS rose steadily and monotonically through the mid-90s and since then has declined steadily. Though people still die from AIDS, this still represents a success story in health policy and science. For those experiencing the personal tragedy of AIDS, this is salvation.

So why did it happen? Well, first, the cause of the disease was correctly identified—the HIV virus—in the mid-80s; and second, by the mid-90s highly active anti-retroviral therapy, or HAART therapy, was able to effectively treat the virus and prevent progression to AIDS.

Again, two things happened: the cause of the disease was correctly identified, and an effective treatment was developed by an enlightened healthcare profession.

This is what success looks like. Now, let’s compare this story to that of obesity and diabetes.

Do we have this situation under control? The case study of “failure”

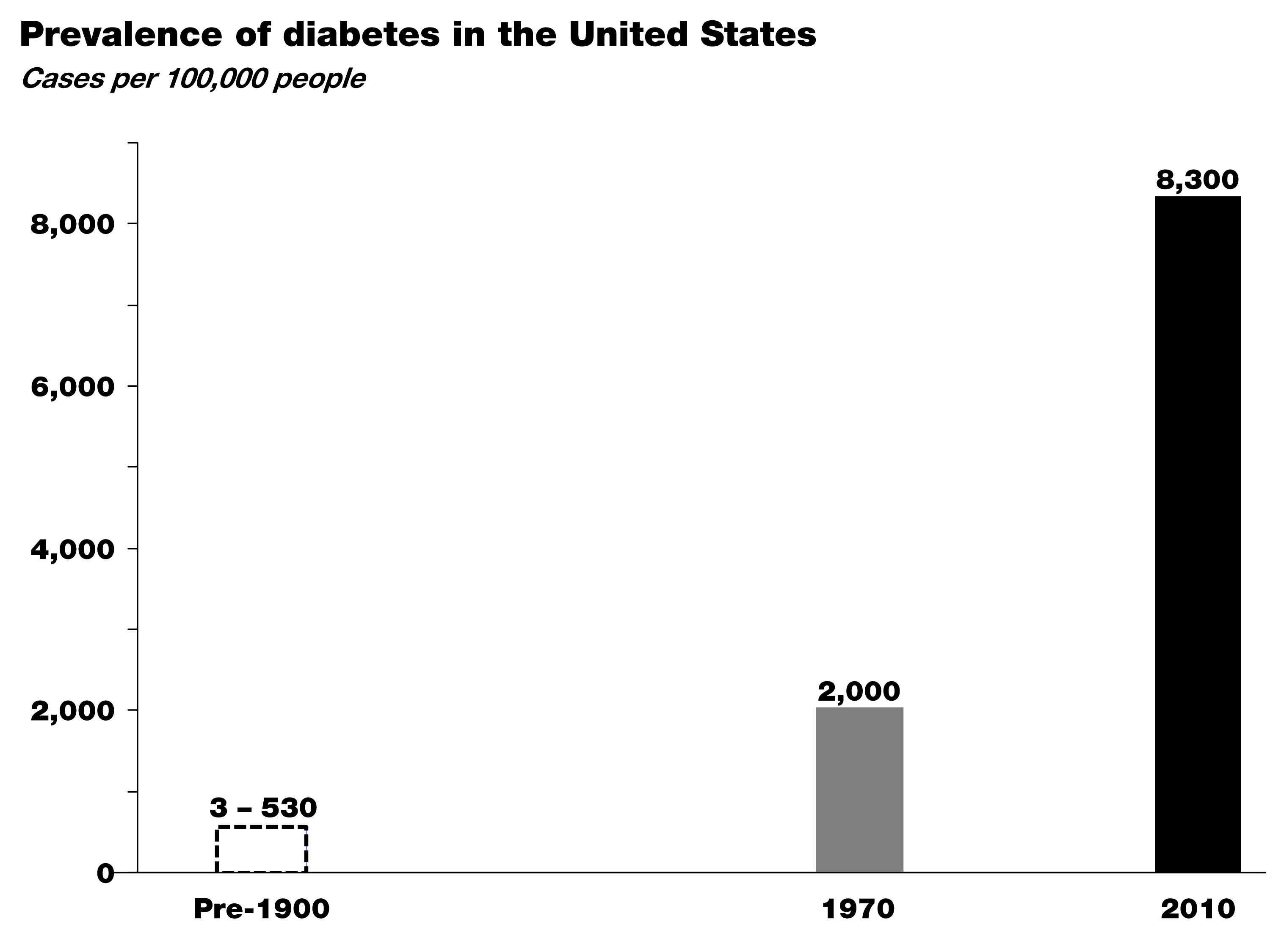

Let’s take a look at this figure. It shows the prevalence of diabetes in the United States over the last hundred-plus years. (Thanks to Gary Taubes who dug up these stats while researching his upcoming book.)

In the early 1900s the leading figures in medicine, Sir William Osler at Johns Hopkins and Elliot Joslin at Mass General, did exhaustive analyses of the number of patients with diabetes based on hospital records and census data. As you can see, diabetes was exceedingly rare in the 19th century—somewhere between about 3 and 500 cases per 100,000, depending on the analysis.

By 1970, around the time I was born, that number was up to 2,000 cases per 100,000, and between 1970 and today—at a growth rate of nearly 4% per year—that number has risen to more than 8,000 cases of diabetes per 100,000.

Worse yet, type 2 diabetes is now spreading into demographics previously naïve to the disease, particularly children. I don’t think any of us in this room today would argue that we have this situation under control. So where are we failing? Many of you understand the world of business. If this were a business, we’d be asking a lot of questions at this point, or we would be out of business. Like any business, we have two possibilities. We either look at our business plan (the basic premise for how we’re going to succeed) or the implementation of that plan (the way we operate on a day-to-day basis). When confronted with a runaway epidemic like this, we have to address the same two basic issues:

Either we understand the underlying cause of this disease and we have a good plan in place, but few individuals have the willpower or wherewithal to avoid the disease—whatever it is…In other words we’re not executing the plan.

Or, we don’t understand the disease in the first place and we’re giving the wrong advice. In other words, we don’t have the right business plan.

In this latter scenario, the failure is not one of personal responsibility, but of our assumptions about the cause of this disease. And these two scenarios have very different implications.

I am not certain which of these is more likely correct, but I do know the risk of ignoring the latter in favor of the former is not a choice we can make any more as a society.

So, maybe the question we should be asking is whether we are right about the environmental triggers of this disease—the underlying cause. Is it as simple as gluttony and sloth and a food industry that overwhelms us with highly-palatable, energy-dense foods, or is there something specific about the quality of the food we’re consuming that triggers these disorders? If we don’t answer this question about what is it in our environment that’s causing this disease correctly, just like we were able to answer it in the mid-80s with HIV’s role in AIDS, we can’t effectively treat the disease. Instead we’re stuck putting on Band-Aids.

Here’s another way to think about it: imagine this panel was on a new crisis in aviation. Planes are constantly crashing—falling out of the sky—and killing 4,000 people a day (just like obesity-related diseases are killing 4,000 Americans a day.) And you’re a pilot and you tell me that surely we understand the principles of flight. Right. Sure, we might suspect user error to be part of the problem. (Maybe the pilots aren’t flapping the wings hard enough!) But, maybe a better idea would be to go back to the drawing board to make sure we really understood this whole aerodynamics thing and we didn’t miss something important?

That’s how we think we have to look at this problem: 4,000 people in this country are effectively falling out of the sky every single day—dying—and we’re saying we’ve got it all figured out, and people just need to adhere better to our advice. I’m not confident that that’s the solution. Nor should you be.

Is there a policy-based solution to this problem?

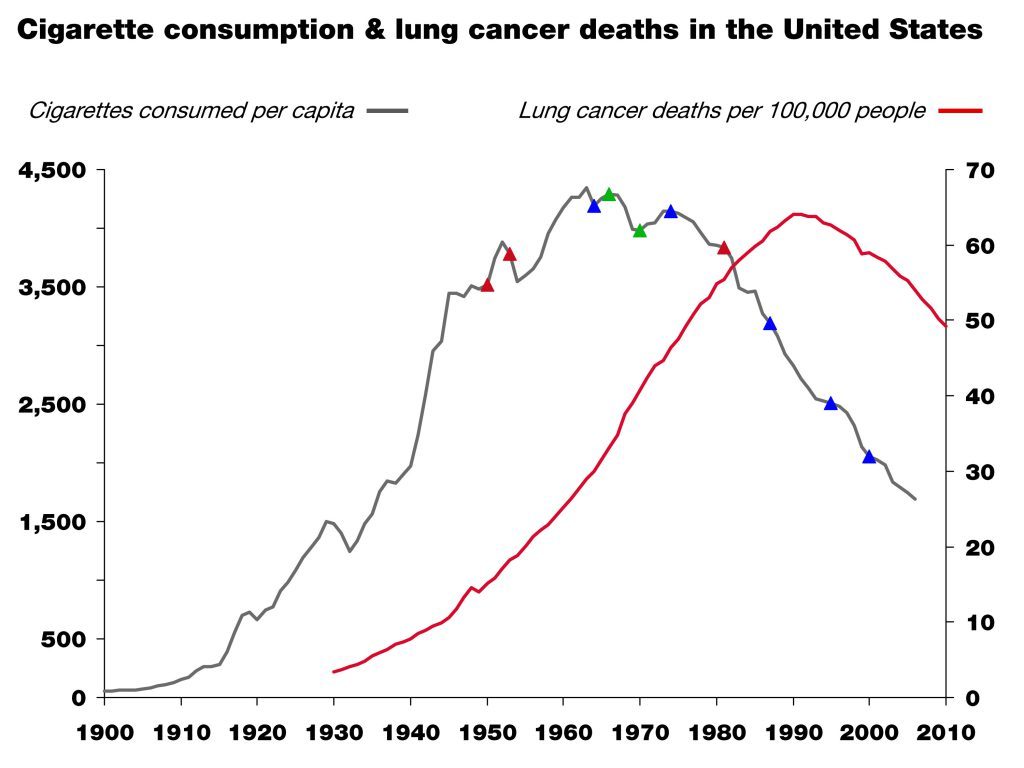

Surely policy changes will play a necessary role in restoring our health. But it may be less about ‘how?’ and more about ‘when?’ I’d like to refer to this slide showing per capita cigarette consumption in the U.S. from 1900 until today—the number of cigarettes consumed is shown in grey with death rate from lung cancer superimposed in red.

This is another success story. People in this room contributed to that success. The little colored triangles on the grey line are major milestones in science (red), market forces (green), and policy (blue). This is a great example of what one might call the “critical confluence”—scientific elucidation, policy action, market response, and behavioral shift—all coming together to save lives.

But, as in all things in life, algebra included, the order of events matters!

Which came first then? In the case of smoking and lung cancer, it was unambiguous scientific clarity, which in this case happened in the 1940s and 50s and resulted in the 1964 Surgeon General’s report. This information was absolutely necessary to drive the policy action, the market response, and the behavioral shift that followed. Without the knowledge that lung cancer is caused by smoking, no amount of policy or market response would have led to the necessary behavioral shift and so a meaningful reduction in lung cancer incidence.

When we consider the current situation with obesity and diabetes, we may still be missing the equivalent of the scientific clarity linking unambiguously the environmental trigger (smoking) that provided the obvious method of prevention (smoking cessation). And, again, if we think we do have that information, we have to ask why we’ve thus far failed to meaningfully prevent and successfully impact these disorders.

If the death rate from AIDS was still skyrocketing, I think we’d all agree we would either call into question our faith in HAART, or even the premise that HIV causes AIDS, if not both. Yet, in the face of skyrocketing obesity and diabetes, we play the who’s-on-first game all day long pointing fingers at people and industry.

Until we clearly identify the dietary triggers of obesity and diabetes, policies to shift behavior may be misguided and premature, despite their best intentions. Despite our best intentions.

I’m arguing that the policies so far may have been just that. Premature. And based on incomplete or faulty information. In other words, we may have the wrong business plan, but we blame our execution of the plan on our failure.

Parting shot

Today, we’re talking about a problem that touches, directly or indirectly, every single person in this room. It’s a topic that can be confusing and at times polarizing. We can’t lose sight of the big picture, which is easy to do when we just look at this problem through the lens of personal responsibility or will power. Remember, I used to think that “If people just learned to eat ‘right,’ (whatever that is), exercise and control themselves and their diet, everyone would be fine.” Today I reject that logic and the hubris that fostered it.

In the business world we know that the wrong strategy, no matter how well implemented, gives us little chance of success. Similarly, the right strategy, if poorly executed, often fails. What we need is the right strategy first and then the right execution second. At the moment, it’s hard to argue that we’re not failing with at least one of these two tasks. The question is which one.

Much of the discussion around this topic focuses on the execution; little attention is paid to the strategy or underlying insights that form the basis of the intervention.

Just 40 years ago the prevalence of obesity in this country was about one-third of what it is today, and that of diabetes about one-fifth. Is this all because Americans have become too gluttonous and slothful and the food industry figured out how to make food cheap and addictive enough? That they simply are too lazy and stubborn to do what we’ve been telling them to do—eat a little less, exercise a little more—for fifty years. Maybe. And I trust many good minds are already working on solutions to address that hypothesis.

However, what if the problem isn’t about non-compliance but about the nature of the advice we’re passing along. Maybe it’s our failure in that we have a simple idea about what causes these diseases, and like many simple ideas—paraphrasing Mencken here—it just happens to be wrong. It’s hard to fathom that two out of three Americans are simply too lazy to be active and too stubborn to eat healthy, despite losing their lives and their loved ones to the negative sequelae of these diseases. I find that hard to believe.

So, what if the problem is that our dietary advice is wrong in the first place? And incorrect dietary advice has resulted in an eating environment where the default for most people is a diet that causes obesity and diabetes?

If HIV or lung cancer were still spiraling out of control—as they were thirty and fifty years ago before the causes were unambiguously identified—the great minds in this country and the world would be leading investigative teams of scientists to figure out what we may have missed in our understanding of the cause of these diseases. We would not be complacent, perhaps because it would be harder to blame these diseases on the victims and their lack of will power. When we fail completely to prevent two devastating disorders for half a century, isn’t it time to investigate what we might have missed—what is it about these disease states that we do not understand? If nothing else, shouldn’t we hedge against the possibility—however slim you think the odds are—that we’re not as smart as we think we are. Those of us who are here today because of our business acumen know the importance of hedges in business. Isn’t it time we did that with obesity and diabetes?