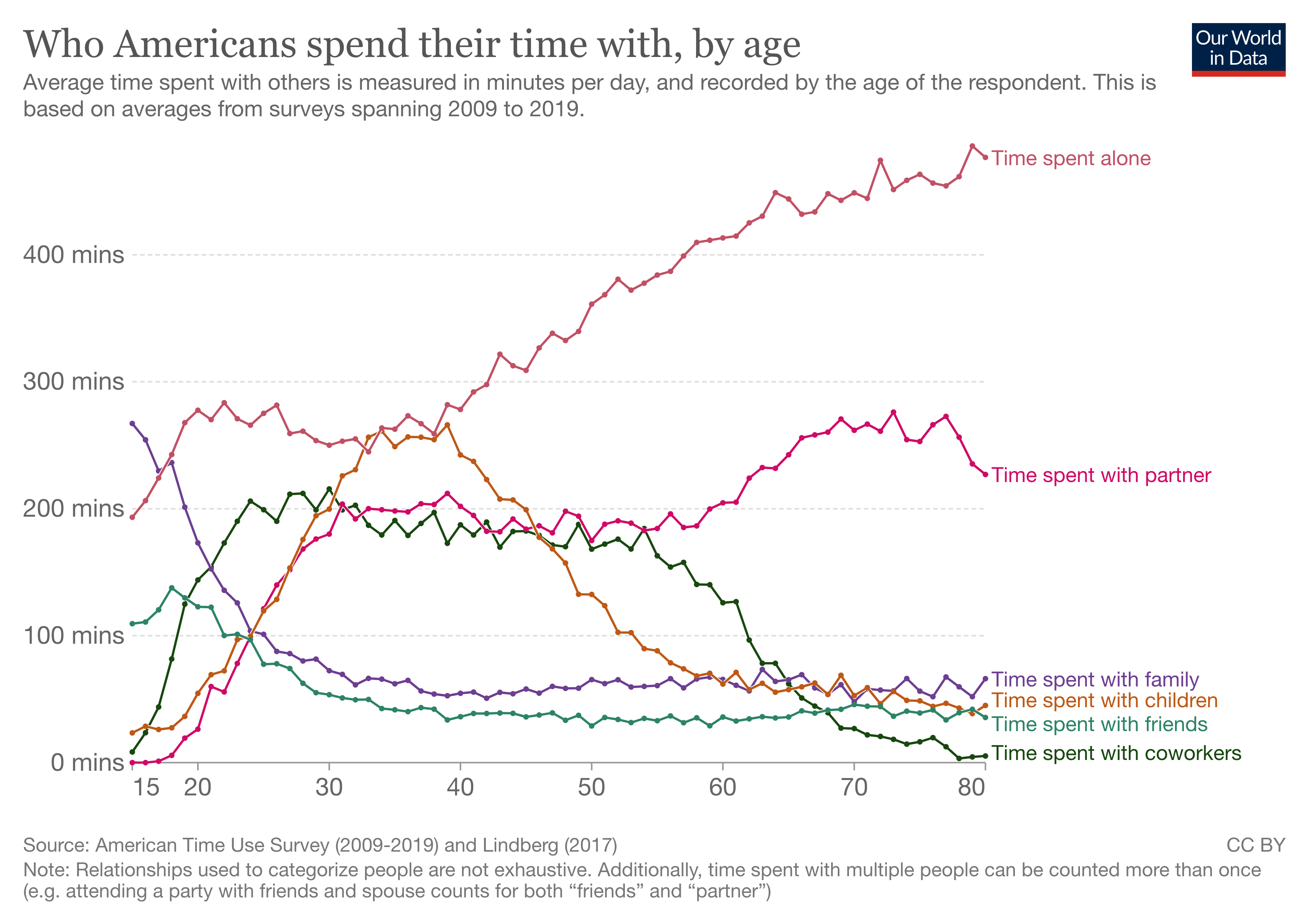

I recently shared a graph on Instagram representing whom we spend time with across our lifetime, collected from 2009 to 2019 as part of the American Time Use Survey (Figure 1). For the most part, the numbers make intuitive sense. The amount of time we spend with our coworkers starts dropping in our mid-fifties as we begin to retire, and time with partners rises concurrently. Time spent with children spikes during the typical child-bearing years of our twenties and thirties and falls again as we reach the “empty nest” stage.

Figure 1: Who Americans spend their time with, by age.

These data demonstrate that most of us enjoy a diversity of social connections daily, and yet, throughout virtually all of our lifespan, we spend more time alone than with any given relationship. Especially eye-catching is the rapid increase in time spent alone after the age of forty, and beyond our early sixties, we spend, on average, more than seven waking hours alone.

Guaranteed loneliness?

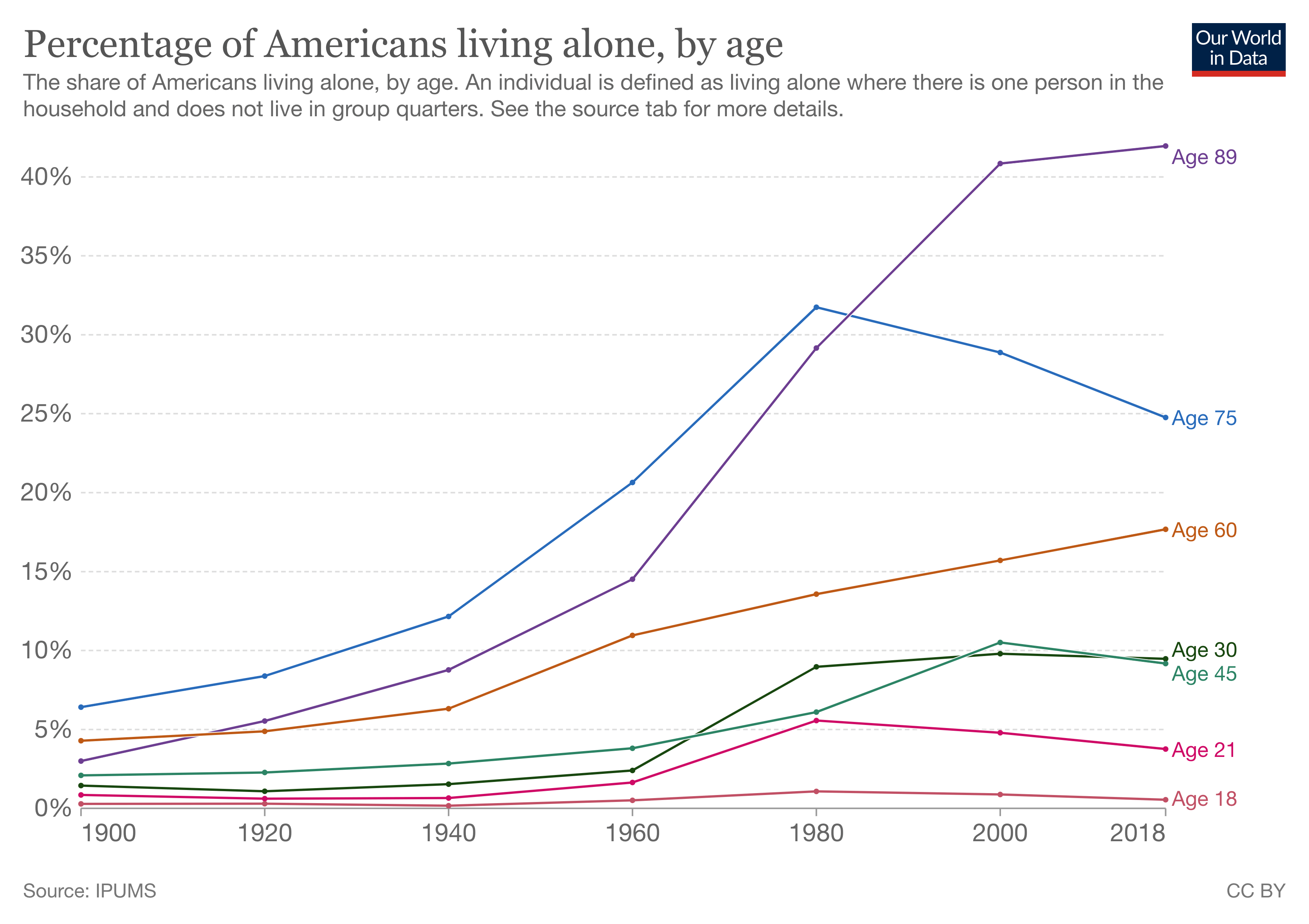

The same article, published by Our World in Data, interestingly shows that the percentage of Americans living alone across all age groups has been increasing throughout history, as shown in Figure 2 (one exception being a recent decline in the age 75 group, though this is likely an artifact of increased life expectancy). In just the past half-century, the proportion of people living alone has almost doubled. In fact, more than 40% of people over the age of 89 live alone. So not only do we spend more time alone as we age, we also spend more time alone than our historical counterparts at all ages. These combined trends raise the question: are we growing lonely?

Despite these statistics, time spent alone does not reflect a loss of meaningful social connection and does not predict loneliness.

Figure 2: Percentage of Americans living alone, by age, from 1900 to 2018.

Solitude vs. loneliness

While solitude is an objective metric – one is either alone or is not – loneliness is subjective. Much like happiness or sadness, it relies on an individual’s perception rather than on quantifiable measures such as hours spent with or without others. Thus, assessment of loneliness must utilize questionnaires, narratives, and other methods that provide insight into participants’ own perceptions.

There are numerous such studies describing trends in loneliness across generations. The general consensus among these studies is that, despite the fact that the percentage of the American population living alone has, on average, been steadily increasing since the early 1900s, loneliness has not. Self-reported loneliness is comparable, for example, between the lifetimes of individuals born in the early and mid-1900s.

In addition to these cross-generational trends, evidence also shows that loneliness does not increase in parallel with time spent alone across an individual’s lifetime. By analyzing two longitudinal survey studies, Hawkley et al. (2019) examined whether older adults became lonelier between 2005 and 2016. The group confirmed a previously reported pattern in which loneliness decreases with age through one’s early seventies before increasing after age 75. Interestingly, evidence from a 2021 study suggests that solitude might even be beneficial to our subjective experience over a certain age span. By employing participant narratives and scale measures with adolescents, adults, and older adults, the researchers showed that the benefits of solitude tend to increase over the lifespan and that older adults report the most relaxed, least lonely mood when in solitude.

What really matters in the end

So, if a decrease in time spent with others does not correlate with increased feelings of loneliness, what does? Recall that although loneliness appears to decrease until our early seventies, Hawkley et al.’s data also showed an increase in self-reported loneliness beyond age 75. Of note, time spent alone appears fairly constant beyond this age at the population level, so what explains the sudden reversal in loneliness trends? The investigators point to two main contributing factors: decline in health and loss of close relationships (primarily due to death, especially of partners). Because the researchers used the data from a survey study focused on intimate and other social relationships, they included parameters other than self-reports of loneliness, such as self-rated health, as well as the number of close family members and friends participants reported.

The impact of declining health on overall well-being is fairly self-evident, but let’s take a closer look at the implications of that second factor. The quality of family and friend relationships is not necessarily reflected in the size of one’s social network overall. While the latter tends to decrease with age, the former often grows. The insights gained from the research data thus confirm previously established patterns: higher self-rated health and stronger close relationships are both significantly associated with a decrease in loneliness.

Bottom line

The graphs above seem to paint a grim picture of being alone as we age. But despite media headlines sounding the alarm on the “pandemic of loneliness,” the significant increase in the time spent alone as we age simply isn’t as relevant to true loneliness as it might first appear. To achieve the greatest possible quality of life in your late adulthood and prevent loneliness, the strategies will sound familiar. Take care of your physical health, as physical and emotional health are highly intertwined, and develop meaningful relationships over shallow social interactions – prioritize “real friends” over “deal friends,” as I discussed in a recent newsletter. The trends in time spent solo in our later years don’t need to be cause for alarm – enjoy the solitude, and embrace the opportunity to devote more attention to those you care about the most. And despite the increased time alone, your golden age won’t be spent lonely.