It seems that every few years, a new documentary promotes plant-based diets as the solution to all of the health woes of modern society, and recently, another has been added to the list.

Released last month on Netflix, You Are What You Eat: A Twin Experiment is a four-part documentary series based on a recently published randomized study comparing the effects of vegan and omnivorous diets. The investigators behind this research (and docuseries) claim that their study design – which involves the use of identical twins to control for genetic factors – has allowed them “to investigate metabolism in a very comprehensive way,” including effects of the respective diets on cardiovascular and metabolic health. So how well did the study accomplish that goal? And what can we take away from the results?

About the study

To investigate the effects of diet without the potential confounds of genetic variation, researchers Landry et al. recruited pairs of identical twins, who were then randomly divided such that for each twin pair, one twin was assigned to a healthy vegan diet while the other was assigned to a healthy omnivorous diet. Additional inclusion criteria included willingness to consume a vegan or omnivore diet for 8 weeks, body weight >100 lb, BMI <40, LDL-C <190 mg/dL, and controlled blood pressure (systolic <160 mmHg, diastolic <90 mmHg).

The eight-week diet intervention involved two phases: in the first four weeks of the study, all meals (7 breakfasts, lunches, and dinners per week) were provided to the participants via a meal delivery company, while in the final four weeks, participants were tasked with providing their own meals according to their assigned diets. Dietary adherence was primarily monitored through unannounced 24-hr dietary recall interviews by a registered dietitian, with three interviews on separate days at baseline, around week 4, and around week 8 (for a total of nine interviews per participant). At each of these three time points, participants also underwent an overnight fast and subsequent blood draw for assessment of LDL-C and other metabolic metrics. Participants also received guidance from health educators throughout the full study.

Among the 21 twin pairs who completed the study, total reported energy intake was lower, relative to baseline, for both vegan and omnivore diets during both phases of the study, though the vegan group had greater energy intake reductions (i.e., consumed fewer calories) than the omnivore group. The vegan diet group also showed a mean LDL-C decrease from baseline of 15.2 mg/dL, compared to a mean decrease of 2.4 mg/dL in the omnivore group at 8 weeks. Using a linear model including fixed effects for diet and time, the authors report these results as a mean LDL-C decrease among vegan diet participants of 13.9±5.8 mg/dL (95% CI: −25.3 to −2.4 mg/dL) at 8 weeks from baseline compared with participants receiving the omnivorous diet. As expected from the lower total energy intake, participants on the vegan diet also demonstrated greater reductions in body weight relative to baseline than participants on the omnivorous diet, though absolute changes in both groups were small.

Satisfaction not guaranteed?

Among the study’s exploratory endpoints were metrics of diet satisfaction, which was reportedly higher for the omnivore group at both week 4 and week 8 than for the vegan group. The lower satisfaction associated with the vegan diet might mean that vegan diets are inherently unpleasant to some, which would lead to poorer adherence in a real-world environment among this fraction of the population. Alternatively, it might mean that starting a vegan diet, particularly from a previously unrestricted omnivore diet, requires an extended period (i.e., more than 8 weeks) to adapt to the new diet pattern – acquiring new tastes, learning new recipes, and so on.

If either of these explanations is true, it would suggest that net reductions in calorie intake and associated metabolic improvements observed by Landry et al. are likely to be short-lived, as those who adopt a vegan diet would either give up the diet fairly quickly or would gradually adapt to it and increase their calorie intake back toward baseline. Lacking any run-in phase, this study was almost certainly too short to permit proper acclimation to veganism and thus to assess the true effect of the diet. (Of note, the detrimental health effects often seen with a vegan diet, such as deficiencies in vitamin B12 and iron, can take months or even years to develop, underscoring the inadequacy of an 8-week intervention for evaluating the health impacts of a plant-based diet.)

Failing Science 101

Though the issue of diet satisfaction limits our ability to interpret the long-term implications of these results, it still is not the most critical shortcoming of this study. By far, that distinction belongs to the investigators’ categorical failure to isolate and test a specific independent variable – which, as emphasized in any sixth-grade science class, is perhaps the most basic requirement for hypothesis testing.

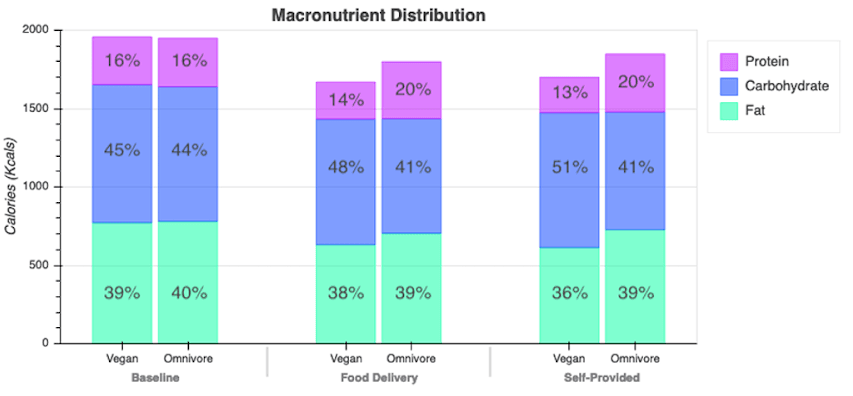

A “diet” is defined by many variables: total calorie intake, macronutrient/micronutrient composition, meal timing, ratio of calories from liquid vs. solid foods, and so on. Even during the first 4-weeks in which all meals were provided, neither total calorie intake nor nutrient composition was controlled between diet groups (see figure below). The vegan group consumed approximately 200 fewer calories per day (~11% of daily calories) than the omnivore group (1628±519 vs 1815±623 kcal/day). Further, despite roughly similar fat content in the diet, fat composition differed dramatically between groups, with the omnivore group consuming far more saturated fat than the vegan group in both study phases (calories from saturated fat: 130±54 vs. 186±100 kcal for vegan vs. omnivore in phase 1; 129±82 vs. 209±112 in phase 2). These differences could easily mean that the increased weight loss and greater reduction in LDL-C relative to baseline among vegan participants were the results of lower intake of total calories and saturated fat rather than to a vegan diet per se.

Some might argue that the reduced intake of total calories and saturated fat are themselves a result of the vegan diet, but this logic fails when we recall that investigators provided all meals for half of the study and thus had total control over calorie intake and diet composition, and throughout the study, participants were advised by health educators as to which foods to consume and in roughly what quantities. In effect, the study was designed such that the vegan diet was more calorie-restricted and lower in saturated fat than the omnivore diet, so is anyone really surprised by the observation that the group given fewer calories and less saturated fat ended up consuming fewer calories and less saturated fat?

“Plant-based”: a meaningless variable

At this point, perhaps one would say that the independent variable was simply whether or not any elements of the diet came from animals. But when we step back from conventional classifications, we start to realize just how meaningless the terms “animal-based foods” and “plant-based foods” really are.

As we all learned in high school biology, the classifications of “plants” and “animals” are defined by a series of shared characteristics and genetics across organisms within each group, but with respect to diet, distinguishing between these two specific kingdoms of life is rather arbitrary. For instance, “plant-based foods” excludes anything from “Kingdom Animalia,” but why not also Kingdom Fungi, which are more closely related to animals than to plants? Why should mushrooms and yeast get a pass for veganism? Should we likewise condemn seaweed (protist) and pickles (bacteria), which are more distantly related to both plants and animals than plants and animals are to each other? The cutoffs lack any clear, underlying reasoning. Why not test a diet that is restricted to the Eudicotae clade of plants? Or to all living things apart from the Bovidae family of animals?

This is to say, whether or not a particular food is derived from animals has no relevance with respect to effects on human health and physiology. In this context, the only important differences between animal-based vs. plant-based foods are in their chemical compositions. And while those between-group differences certainly exist, the within-group variation is so large that it could conceivably overshadow the between-group trends. Plant-based foods, for example, tend to have less saturated fat than animal-based foods, but not all plant-based foods are lower in saturated fat than all animal-based foods: a single serving of Oreo cookies (which are vegan) contains twice the saturated fat of a single 3-oz serving of skinless chicken.

So in essence, when looking for effects on health, a diet must be defined by its composition – not by whether or not it includes foods derived from animals. The latter is scarcely more relevant than the clothes you wear to the grocery store or whether you use a self-checkout lane.

The larger context

I could go on for days about other shortcomings of this study – such as their reliance on self-reported food surveys or the fact that participants were free to purchase snacks on their own during the food delivery phase – but harping on such small-scale points seems superfluous when the basic study design and the entire premise upon which it is based are so deeply flawed. While the attempt at controlling for genetics may be admirable, it is at odds with the rest of the study design, which fails utterly to isolate and test a specific independent variable. Indeed, if we can derive any knowledge at all from this research, it is that calorie restriction and healthy diet composition – regardless of whether foods come from plants or animals – can improve metabolic health. Surprise, surprise.

Still, the fact that I find no value in this study should not be interpreted as an indication that I believe plant-based diets have no utility or are inherently “worse” than omnivorous diets. Veganism is, for some, an effective means of reducing overall calorie intake and in improving diet composition through dietary restriction – while for others, time-restricted feeding or a low-carbohydrate diet might accomplish these goals more effectively than veganism. And while cutting “animal-based foods” might be arbitrary from a health standpoint, for many individuals and populations, considerations related to environmental impact, religious beliefs, or animal welfare may provide a more meaningful justification for the distinction.

This latest in the line of pro-vegan documentaries certainly doesn’t shy away from hammering these other motivations. From the existential crisis of a world-class chef to gimmicky blacklight tests for kitchen hygiene to pig feces raining down on a Carolina home, many scenes border on the absurd and blow past even the most generous limits of relevance to the questions that Landry et al. aimed to investigate. Then again, perhaps this chaotic, three-ring circus of a docuseries serves to highlight the nonsense of the study itself, and for those of us for whom health is our top dietary concern, this “research” should be taken for just what it is – entertainment, not rigorous science.

For a list of all previous weekly emails, click here.