Once you realize how harmful sugar is (by sugar, of course, I mean sucrose and high fructose corn syrup or HFCS, primarily, but also the whole cast of characters out there like cane sugar, beet sugar, dextrose, corn syrup solids, and others that masquerade as sugar), you inevitably want to understand the impact of substituting non-sugar sweeteners for sugar, should you still desire a sweet taste.

Want more content like this? Check out my article on replacing sugar with allulose and my Ask Me Anything (AMA) podcast on sugar and sugar substitutes.

If you’re not yet convinced sugar is a toxin, it’s probably worth checking out my post, Sugar 101, and the accompanying lecture by Dr. Lustig. Sugar is, tragically, more prevalent in our diets today than we realize – our intake of sugar today is about 400% of what it was in 1970. And it’s not just in the “obvious” places, like candy bars and soda drinks, where sugar is showing up, either. It’s in salad dressings, pasta sauces, cereals, “healthy” sports bars and drinks, low-fat “healthy” yogurt, and most lunch meats, just to name a few places sugar sneaks into our diet.

I know some people have an aversion to aspartame (i.e., Nutrasweet, Equal) over sucrose (i.e., table sugar, sucrose, or HFCS). In other words they think Coke is “better” that Diet Coke because it uses “real” sugar instead of “fake” sugar. If you find yourself in this camp, but you’re now realizing “real” sugar is a toxin, this poses a bit of a dilemma.

There are two things I think about when considering the switch from sugar to non-sugar substitute sweeteners:

- Are non-sugar sweeteners more or less chronically harmful than sugar?

- What are the immediate metabolic impacts of consuming these products, relative to sugar?

Let’s address these questions in order.

Question 1: Are artificial (i.e., non-sugar or substitute) sweeteners more chronically harmful than sucrose/HFCS?

There’s no shortage of fear out there that consuming aspartame, sucralose, or other non-sugar substitute sweeteners will lead to chronic diseases like cancer or heart disease. However, there is no credible evidence of this in humans. One can actually make a convincing case that no substance ingested by humans has been more thoroughly tested by the FDA than aspartame. The former Commissioner of the FDA noted, “Few compounds have withstood such detailed testing and repeated, close scrutiny, and the process through which aspartame has gone should provide the public with additional confidence of its safety.” While it might be the case that you can harm a rat with aspartame, it seems you need to force the rat to eat its bodyweight in aspartame every day for a year to do so (I’m being a bit facetious, but you get the idea). In fact, even water would be harmful to us in the quantities required to render aspartame harmful if we extrapolate from rat studies.

Since its invention/discovery in 1965, there is not a single well-documented case of chronic harm to a human from ingesting aspartame, and prior to its approval for human consumption in the early 1980’s it had been studied in approximately 100 independent studies. A possible exception to this might be in the rare person with phenylketonuria (PKU). Such folks lack an enzyme required to metabolize a breakdown product of aspartame.

So, aside from the rare person with PKU, does this mean aspartame is 100% harmless? Not necessarily. 100% harmless is a pretty high bar. “Harmless,” using air travel as an analogy, is not getting on an airplane at all. Consuming aspartame is more like getting on a commercial airplane – statistically speaking you are very safe, but something bad could happen that we’re not aware of yet. Consuming sugar in the amounts we typically do, by contrast, is downright harmful. “Harmful,” by the air travel analogy, is not only getting on an airplane but skydiving with a poorly-packed parachute – you might make it, but you’re really taking a chance.

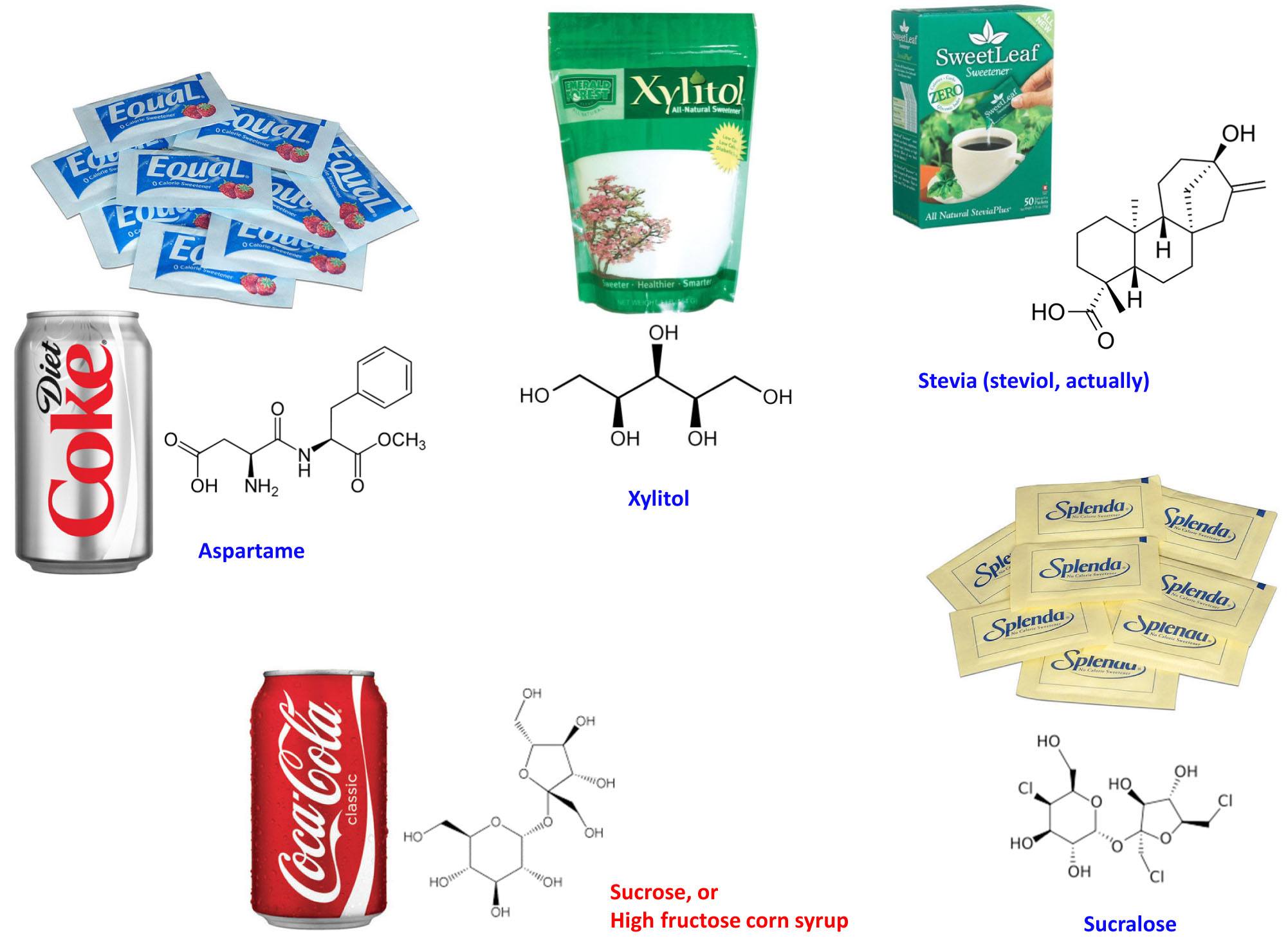

As far as other non-sugar substitute sweeteners go (e.g., sucralose, saccharin, stevia, xylitol), the same logic holds except that we don’t have quite as much data on them because most of them (see figure, below, for the most popular ones) haven’t been on our tables quite as long as aspartame. However, to date there are no data linking these substances to the diseases people tend to erroneously link them to in casual conversation.

Question 2: What are the metabolic differences between sugar and non-sugar substitute sweeteners?

The metabolic effects of table sugar (sucrose) and high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) are well understood, so I won’t review them again. If you want a quick review of sugar and why it’s probably as chronically harmful as tobacco, see my previous post on the topic. Also, Dr. Lustig and his colleagues last week published a paper in the journal Nature titled, The toxic truth about sugar, which you may want to check out if you have a subscription to Nature. The press picked this up in spades, also, and here is one such story.

So how do non-sugar substitute sweeteners compare to sucrose/HFCS in the acute or immediate metabolic phase? Most non-sugar sweeteners (e.g., aspartame, saccharin, sucralose, stevia) are much more potent in their sweetness relative to sucrose, and therefore require a fraction of the amount to give the same “sweetness” as sucrose. So for these sweeteners, only a fraction of the substance is required for equal sweetness. That’s why when you look at a can of Diet Coke it has no calories in it. The amount of aspartame that’s used is so small (given its sweetness), it doesn’t even add a calorie worth of energy. Hence, we consume a fraction of them, relative to “real” sugar to get the same sweetness.

Other non-sugar substitute sweeteners, such as alcohol sugars (e.g., xylitol, sorbitol), are not actually sweeter than sucrose, but they have very different metabolic and digestive properties. Furthermore, one actually uses similar amounts of these sweeteners, relative to sucrose (e.g., substituting an alcohol sugar in the place of sucrose occurs at about a one-to-one ratio). In other words, when consuming alcohol sugars you actually ingest non-zero calories of them. This is why you’ll note non-zero amounts of them when you look at the ingredient labels of foods containing them. Even a piece of gum sweetened with alcohol sugars contains 1 to 2 grams per piece. While an excess of alcohol sugars can cause gastrointestinal distress (e.g., if you overdo it on these you can get diarrhea), in most people they do not cause secretion of insulin from the pancreas due to their distinct chemical structure (see figure of their structures, above).

The same is true for the first group of non-sugar substitute sweeteners I mentioned (e.g., aspartame, saccharin, sucralose), with respect to the lack of insulin response. In addition to studies confirming this, I’ve also documented this in myself for xylitol (my personal favorite), aspartame (Equal), and sucralose (Splenda). I cannot speak to the other substitute non-sugar sweeteners in myself, but these three compounds seem to pass through my digestive tract without ever alerting my pancreas (i.e., without stimulating insulin). When I consume these non-sugar sweeteners neither my blood glucose nor insulin levels rise.

I should point out that some people have noted/suggested a cephalic insulin response to non-sugar substitute sweeteners. A cephalic insulin response occurs when the pancreas begins to secrete insulin before the “meal” actually gets into the bloodstream – the usual step required for the pancreas to secrete insulin. In other words, the anticipation of the meal leads to the release of insulin. This has been documented in humans, and a few studies have attempted to elucidate the mechanism indirectly by using various drugs to attempt to block this response. Furthermore, some have suggested that you can still experience the harmful effects of regular soda while consuming an equal amount of diet soda. It’s not clear to me this is true. First, this hypothesis has never been studied rigorously (i.e., prospectively and with random assignment in a controlled setting). Second, if there is some cephalic insulin response to non-sugar sweeteners, it is probably significantly less than that of sugar in both magnitude and duration, based on the studies I’ve read. To reiterate a common theme – this phenomenon is probably minimal in most people but significant in others. When I work with people who seem to be doing everything “right” but can’t seem to make improvements (e.g., fat loss), I will usually suggest removing all non-sugar substitute sweeteners to test this hypothesis.

Lastly, there has been some recent discussion about how diet soda may cause even more harm than regular soda. A few observational studies have commented on this, including a study released last week in the Journal of General Internal Medicine. Due to time and space, I’m not going to comment broadly on this paper in this post (though I will write a great deal more about this sort of study in the future). I do want to make one very important point that is true of virtually every study of this nature: it is impossible to make a correct inference without doing a prospective, random-assignment, controlled trial.

While the authors of this study acknowledge that “further study is warranted,” the lay press picks up the title of this paper: Diet soft drink consumption is associated with an increased risk of vascular events in the Northern Manhattan study, and fails to ask any questions. While I am not trying to be overly critical of the study authors (whom I do not know, either personally or by reputation), I am actually quite critical of the press that like to report on bumper-sticker messages without reading the fine print. Most people (including many policy makers, who are bombarded with this sort of bumper-sticker information) tend to form their opinions based on this sort of information.

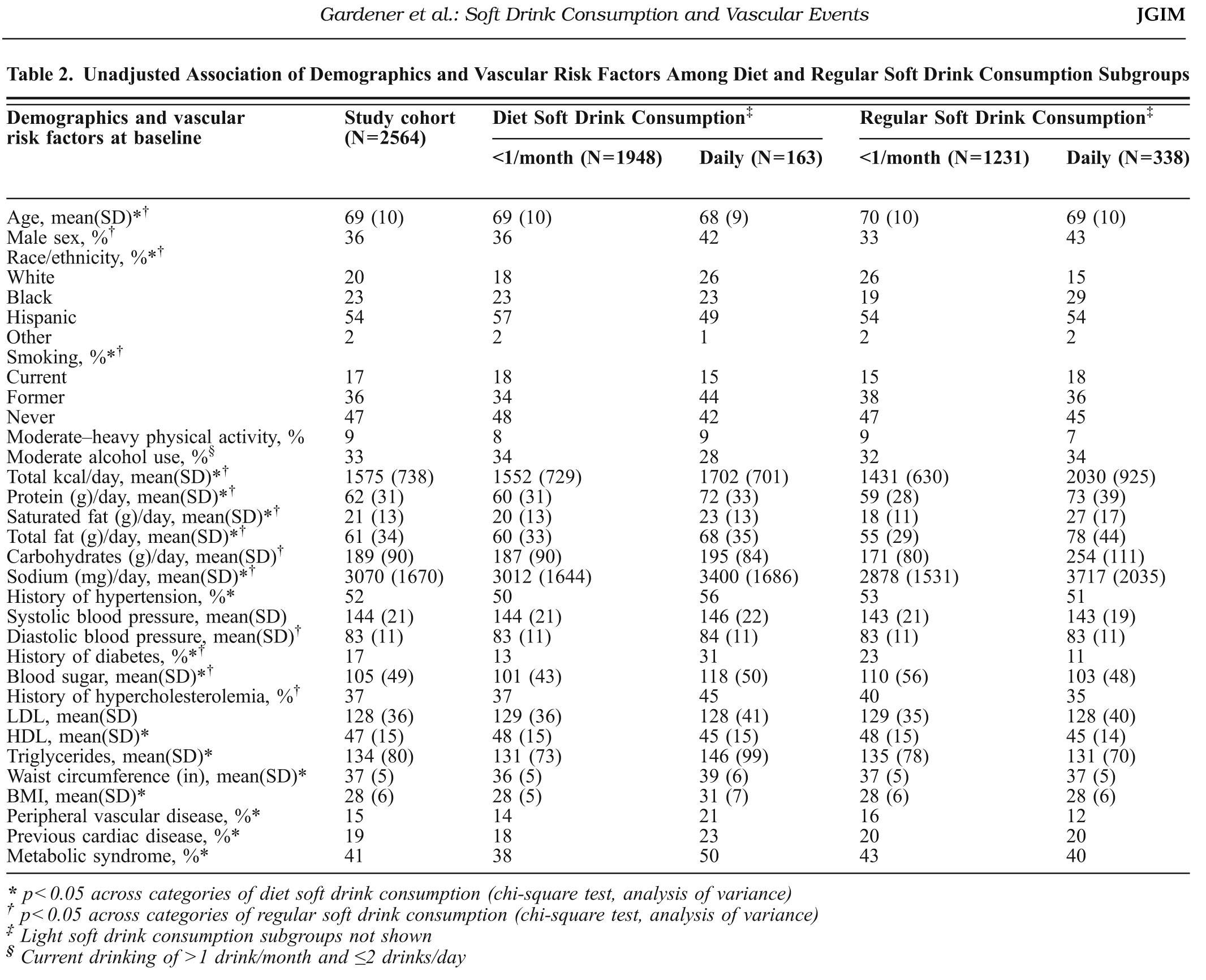

A table from this study (Table 2) is shown below. It’s a bit hard to read unless you click on it, which I’d suggest you do to see what I’m talking about. The group of 163 people who consumed diet soft drinks daily had worse clinical outcomes than the group of 1,948 people who consumed no more than 1 diet soft drink per month (all self-reported). That is, the people who drank more diet soda were more likely to have a vascular “event” (on a per person basis). Seems pretty bad, right? Is drinking diet soda actually causing this?

Well, let’s double-click on this question. Note that the people who were consuming daily diet soda (relative to those not) also had a few other factors not working in their favor including higher blood pressure, higher circulating triglycerides, a higher rate of diabetes, higher BMI, lower HDL-C, higher pre-existing vascular disease, a higher rate of metabolic syndrome, and a higher rate of previous cardiac surgery just to name a few. And in many of these factors the difference between the groups was very large (e.g., diabetes, history of peripheral vascular disease). You will also note that both groups of diet soft drink consumers reported between 1,500 and 1,700 calories per day, below the national average, suggesting yet another problem with this sort of study — self-reporting.

The authors try to correct for this obvious shortcoming by employing a statistical technique called “adjustment.” This means you try to “strip out” the differences between groups and see if the effect still holds. I do not want to turn this into a detailed post on elaborate statistics (a topic I greatly enjoy), but it’s REALLY important that you understand why this is a dangerous way to conduct science. The reason this is “dangerous” is that it only proves an association exists, not that there is any causal link between drinking diet soda and getting cardiovascular disease.

If anyone is really interested in the details of this, I actually reached out to my thesis adviser who did his Ph.D. in applied statistics at Berkeley at the age of 20 (and is one of the smartest people I’ve ever met). Just to make sure I hadn’t gone too far off the reservation, I asked him his view. Here was his response:

Do I buy the analysis? The unadjusted data (Table 2) is pretty hard to disagree with. The adjusted results are open to debate, because the conclusions depend on the form of the model that the authors proposed. A Cox proportional hazards model assumes that the predictors enter linearly into the model. This form is chosen for computational and mathematical convenience, not because anybody has a convincing argument for why the model is correct. But it’s the most popular model out there for survival analysis.

Remember also that the study is observational, not a controlled experiment. The authors can’t conclude that the diet soda is the cause of the greater disposition toward a vascular event, only that there is an association.

My translation: Taken as-is (i.e., unadjusted) there is no way to draw any conclusion from this. After statistical adjustment, you might be able to make the case that it’s worth looking into things further, but as it stands there is only an association between consuming diet soda and having a vascular event.

Want another way to think about? Think of a simple (and silly) example: I once read (I’m not making this up) that people with red cars are more likely to get into car accidents. Let’s assume this is true (though I can’t confirm it). Does it mean owning a red car causes you to have a higher chance of getting into a car accident? Or is it more likely that someone who buys a red car may drive in such way that they are more likely to have an accident? My guess is, even if this correlation between car color and accident frequency were true, there is no causal information contained within it.

Yes, it is possible the reporting of all behavior (e.g., intake) was accurate, and yes it is possible that, even when adjusting for these pre-existing differences between the groups, the outcome would have been the same. But is it likely? It is very hard for me to believe this.

There is a reason I refer (only half-jokingly) to observational epidemiology studies as “scientific weapons of mass destruction.” If you remember nothing else I write or say, please remember this: Never confuse association with causation. If we want to definitively know the answer to this question, we need to design a prospective, well-controlled, random-assignment experiment.

So what is the upshot of all of this?

I would argue (along with a legion of others) that once you eliminate sugar from your diet, your cravings for sugar actually vanish. So the question, rather than, Is it ok to consume sugar substitutes?, may actually be: Why do we need things to be sweet in the first place?

I think this is a personal choice, and something worthy of self-experimentation. I know many people who have eliminated everything sweet (both sugar and non-sugar sweeteners) from their diet, and within weeks they completely lose the desire or craving for sweet foods. Others (like me) still like the occasional taste of sweet things. One of my favorite snacks is home-made whip cream (heavy cream whipped with a touch of xylitol). But the point is this: despite occasionally consuming sugar substitutes I’ve really shed my pathologic need for sweet things. There was a day when I needed something sweet with every meal. That’s no longer true. I go days without ingesting anything sweet and don’t miss it. Other days, I feel like having some xylitol-enriched whip cream, or drinking a Diet Dr. Pepper, and I do so. Would I be better off without them? Maybe. But now we’re well past first-, second-, and third-order terms. (For a refresher on the concept of “ordered terms,” check out my post on irisin).

In summary, if you must drink a sweet beverage (or add sweetener to your coffee or tea) you are better off using a substitute for sugar than you are using sugar. But if you want to be really sure, and you want to kick the habit of needing a sweet taste, you’re probably better off avoiding substitute sweeteners altogether. If you want to be 100% safe, drink water. Just don’t make it bottled water (though that’s a whole other story). And don’t fly in airplanes or drive in cars, either.