Author’s note: This post was originally published in May, 2014. It has been updated to reflect my current thinking on the topic. Perhaps the best addition, by popular demand, is Rik’s coffee recipe (click the 1st inline footnote).

§

In 2012, I was having dinner with a good friend, Rik Ganju, who is one of the smartest people I know. And one of the most talented, too—a brilliant engineer, a savant-like jazz musician, a comedic writer, and he makes the best coffee I’ve ever had.1Here is the coffee recipe, courtesy Rik. I make this often and the typical response is, “Why are you not making this for a living?” Look for Vietnamese cinnamon, also known as Saigon cinnamon; you need two big dashes, if that. You need real vanilla (be careful to avoid the cheap versions with added sugar). Best is dissolved in ethanol; if that doesn’t work for you get the dried stick and scrape the pods. Then find a spice store and get chicory root (I’m a bit lazy and get mine on Amazon). You’ll want to replace coffee beans with ~10% chicory on a dry weight basis. If you’re on a budget, cut your coffee with Trader Joe’s organic Bolivian. But do use at least 50% of your favorite coffee by dry weight: 50-40-10 (50% your favorite, 40% TJ Bolivian, 10% other ingredients [chicory root, cinnamon, vanilla, amaretto for an evening coffee]) would be a good mix to start. Let it sit in a French press for 6 minutes then drink straight or with cream, but very little–max is 1 tablespoon of cream. The Rik original was done with “Ether” from Philz as the base. I was whining to him about my frustration with what I perceived to be a lack of scientific literacy among people from whom I “expected more.” Why was it, I asked, that a reporter at a top-flight newspaper couldn’t understand the limitations of a study he was reporting on? Are they trying to deliberately mislead people, or do they really think this study which showed an association between such-and-such, somehow implies X?

Rik just looked at me, kind of smiled, and asked the question in another way. “Peter, give me one good reason why scientific process, rigorous logic, and rational thought should be innate to our species?” I didn’t have an answer. So as I proceeded to eat my curry, Rik expanded on this idea. He offered two theses. One, the human brain is oriented to pleasure ahead of logic and reason; two, the human brain is oriented to imitation ahead of logic and reason. What follows is my attempt to reiterate the ideas we discussed that night, focusing on the second of Rik’s postulates—namely, that our brains are oriented to imitate rather than to reason from first principles or think scientifically.

One point before jumping in: This post is not meant to be disparaging to those who don’t think scientifically. Rather, it’s meant to offer a plausible explanation. If for no other reason, it’s a way for me to capture an important lesson I need to remember in my own journey of life. I’m positive some will find a way to be offended by this, which is rarely my intention in writing, but nevertheless I think there is something to learn in telling this story.

The evolution of thinking

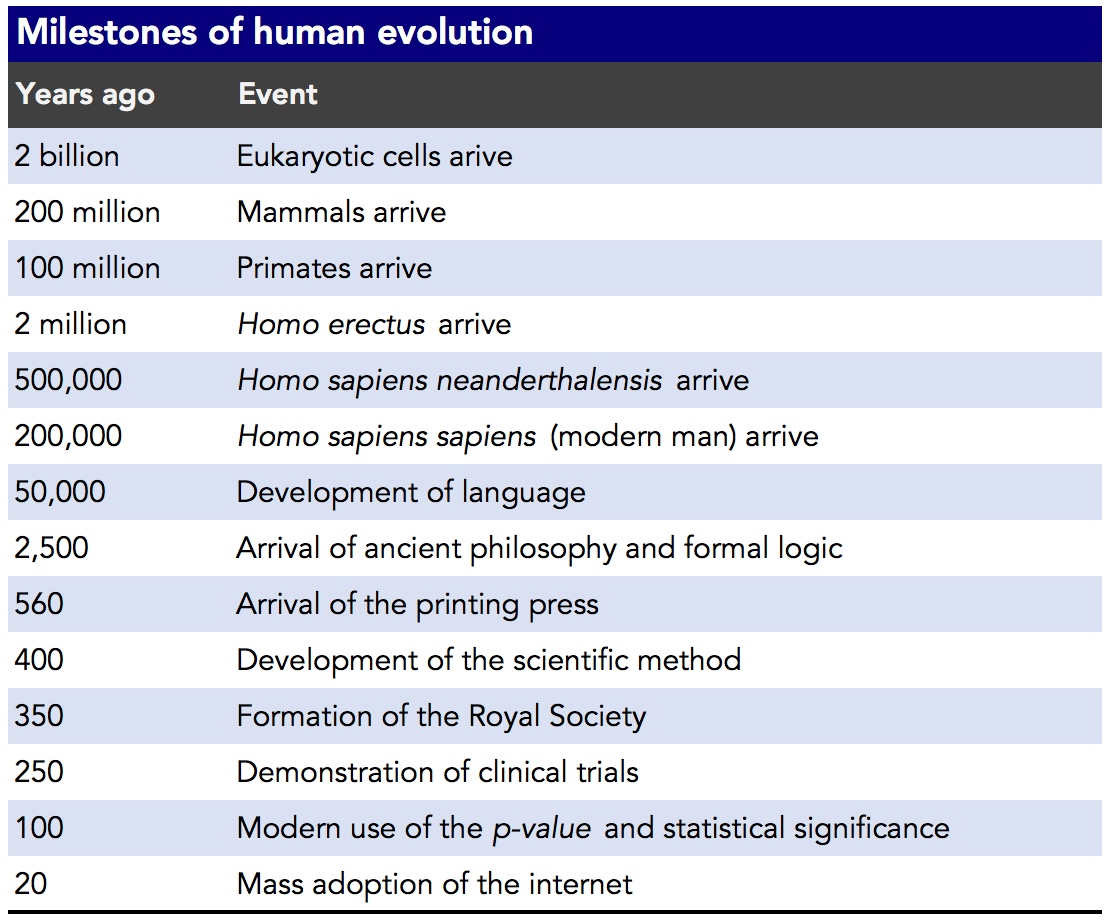

Two billion years ago, we were just cells acquiring a nucleus. A good first step, I suppose. Two million years ago, we left the trees for caves. Two hundred thousand years ago we became modern man. No one can say exactly when language arrived, because its arrival left no artifacts, but the best available science suggests it showed up about 50,000 years ago.

I wanted to plot the major milestones, below, on a graph. But even using a log scale, it’s almost unreadable. The information is easier to see in this table:

Formal logic arrived with Aristotle 2,500 years ago; the scientific method was pioneered by Francis Bacon 400 years ago. Shortly following the codification of the scientific method—which defined exactly what “good” science meant—the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge was formed. So, not only did we know what “good” science was, but we had an organization that expanded the application, including peer review, and existed to continually ask the question, “Is this good science?”

While the Old Testament makes references to the earliest clinical trial—observing what happened to those who did or did not partake of the “King’s meat”—the process was codified further by 1025 AD in The Canon of Medicine, and formalized in the 18th century by James Lind, the Scottish physician who discovered, using randomization between groups, the curative properties of oranges and lemons—vitamin C, actually—in treating sailors with scurvy. Hence the expression, “Limey.”

The concept of statistical significance is barely 100 years old, thanks to Ronald Fisher, the British statistician who popularized the use of the p-value and proposed the limits of chance versus significance.

The art of imitation

Consider that for 2 million years we have been evolving—making decisions, surviving, and interacting—but for only the last 2,500 years (0.125% of that time) have we had “access” to formal logic, and for only 400 years (0.02% of that time) have we had “access” to scientific reason and understanding of scientific methodologies.

Whatever a person was doing before modern science—however clever it may have been—it wasn’t actually science. And along the same vein, how many people were practicing logical thinking before logic itself was invented? Perhaps some were doing so prior to Aristotle, but certainly it was rare compared to the time following its codification.

Options for problem-solving are limited to the tools available. The arrival of logic was a major tool. So, too, was the arrival of the scientific method, clinical trials, and statistical analyses. Yet for the first 99.98% of our existence on this planet as humans—literally—we had to rely on other options—other tools, if you will — for solving problems and making decisions.

So what were they?

We can make educated guesses. If it’s 3,000 BC and your tribemate Ugg never gets sick, all you can do to try to not get sick is hang out where he hangs out, wear similar colors, drink from the same well—replicate his every move. You are not going to figure out anything from first principles because that isn’t an option, any more than traveling by jet across the Pacific Ocean was an option. Nothing is an option until it has been invented.

So we’ve had millions of years to evolve and refine the practice of:

Step 1: Identify a positive trait (e.g., access to food, access to mates),

Step 2: Mimic the behaviors of those possessing the trait(s),

Step 3: Repeat.

Yet, we’ve only had a minute fraction of that time to learn how to apply formal logic and scientific reason to our decision making and problem solving. In other words, evolution has hardwired us to be followers, copycats if you will, so we must go very far out of our way to unlearn those inborn (and highly refined) instincts to think logically and scientifically.

Recently, neuroscientists (thanks to the advent of functional MRI, or fMRI) have been asking questions about the impact of independent thinking (something I think we would all agree is “healthy”) on brain activity. I think this body of research is still in its infancy, but the results are suggestive, if not somewhat provocative.

To quote the authors of this work, “if social conformity resulted from conscious decision-making, this would be associated with functional changes in prefrontal cortex, whereas if social conformity was more perceptually based, then activity changes would be seen in occipital and parietal regions.” Their study suggested that non-conformity produced an associated “pain of independence.” In the study-subjects the amygdala became most active in times of non-conformity, suggesting that non-conformity—doing exactly what we didn’t evolve to do—produced emotional distress.

From an evolutionary perspective, of course, this makes sense. I don’t know enough neuroscience to agree with their suggestion that this phenomenon should be titled the “pain of independence,” but the “emotional discomfort” from being different—i.e., not following or conforming—seems to be evolutionarily embedded in our brains.

Good solid thinking is really hard to do as you no doubt realize. How much easier is it to economize on all this and just “copy & paste” what seemingly successful people are doing? Furthermore, we may be wired to experience emotional distress when we don’t copy our neighbor! And while there may have been only 2 or 3 Ugg’s in our tribe 5,000 years ago, as our societies evolved, so too did the number of potential Ugg’s (those worth mimicking). This would be great (more potential good examples to mirror), if we were naturally good at thinking logically and scientifically, but we’ve already established that’s not the case. Amplifying this problem even further, the explosion of mass media has made it virtually, if not entirely, impossible to identify those truly worth mimicking versus those who are charlatans, or simply lucky. Maybe it’s not so surprising the one group of people we’d all hope could think critically—politicians—seems to be as useless at it as the rest of us.

So we have two problems:

- We are not genetically equipped to think logically or scientifically; such thinking is a very recent tool of our species that must be learned and, with great effort, “overwritten.” Furthermore, it’s likely that we are programmed to identify and replicate the behavior of others, rather than think independently, and independent thought may actually cause emotional distress.

- The signal (truly valuable behaviors worth mimicking)-to-noise (all unworthy behaviors) ratio is so low—virtually zero—today that the folks who have not been able to “overwrite” their genetic tendency for problem-solving are doomed to confusion and likely poor decision making.

As I alluded to at the outset of this post, I find myself getting frustrated, often, at the lack of scientific literacy and independent, critical thought in the media and in the public arena more broadly. But, is this any different than being upset that Monarch butterflies are black and orange rather than yellow and red? Marcus Aurelius reminds us that you must not be surprised by buffoonery from buffoons, “You might as well resent a fig tree for secreting juice.”

While I’m not at all suggesting people unable to think scientifically or logically are buffoons, I am suggesting that expecting this kind of thinking as the default behavior from people is tantamount to expecting rhinoceroses not to charge or dogs not to bark—sure it can be taught with great patience and pain, but it won’t be easy in short time.

Furthermore, I am not suggesting that anyone who disagrees with my views or my interpretations of data frustrates me. I have countless interactions with folks whom I respect greatly but who interpret data differently from me. This is not the point I am making, and these are not the experiences that frustrate me. Healthy debate is a wonderful contributor to scientific advancement. Blogging probably isn’t. My point is that critical thought, logical analysis, and an understanding of the scientific method are completely foreign to us, and if we want to possess these skills, it requires deliberate action and time.

What can we do about it?

I’ve suggested that we aren’t wired to be good critical thinkers, and that this poses problems when it comes to our modern lives. The just-follow-your-peers-or-the-media-or-whatever-seems-to-work approach simply isn’t good enough anymore.

But is there a way to overcome this?

I don’t have a “global” (i.e., how to fix the world) solution for this problem, but the “local” (i.e., individual) solution is quite simple provided one feature is in place: a desire to learn. I consider myself scientifically literate. Sure, I may never become one-tenth a Richard Feynman, but I “get it” when it comes to understanding the scientific method, logic, and reason. Why? I certainly wasn’t born this way. Nor did medical school do a particularly great job of teaching it. I was, however, very lucky to be mentored by a brilliant scientist, Steve Rosenberg, both in medical school and during my post-doctoral fellowship. Whatever I have learned about thinking scientifically I learned from him initially, and eventually from many other influential thinkers. And I’m still learning, obviously. In other words, I was mentored in this way of thinking just as every other person I know who thinks this way was also mentored. One of my favorite questions when I’m talking with (good) scientists is to ask them who mentored them in their evolution of critical thinking.

Relevant aside: Take a few minutes to watch Feynman at his finest in this video—the entire video is remarkable, especially the point about “proof,”—but the first minute is priceless and a spot on explanation of how experimental science should work.

You may ask, is learning to think critically any different than learning to play an instrument? Learning a new language? Learning to be mindful? Learning a physical skill like tennis? I don’t think so. Sure, some folks may be predisposed to be better than others, even with equal training, but virtually anyone can get “good enough” at a skill if they want to put the effort in. The reason I can’t play golf is because I don’t want to, not because I lack some ability to learn it.

If you’re reading this, and you’re saying to yourself that you want to increase your mastery of critical thinking, I promise you this much—you can do it if you’re willing to do the following:

- Start reading (see starter list, below).

- Whenever confronted with a piece of media claiming to report on a scientific finding, read both the actual study and the media, in that order. See if you can spot the mistakes in reporting.

- Find other like-minded folks to discuss scientific studies. I’m sure you’re rolling your eyes at the idea of a “journal club,” but it doesn’t need to be that formal at all (though years of formal weekly journal clubs did teach me a lot). You just need a good group of peers who share your appetite for sharpening their critical thinking skills. In fact, we have a regularly occurring journal club on this site (starting in January, 2018).

I look forward to seeing the comments on this post, as I suspect many of you will have excellent suggestions for reading materials for those of us who want to get better in our critical thinking and reasoning. I’ll start the list with a few of my favorites, in no particular order:

- Anything by Richard Feynman (In college and med school, I would not date a girl unless she agreed to read “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman”)

- The Transformed Cell, by Steve Rosenberg

- Anything by Karl Popper

- Anything by Frederic Bastiat

- Bad Science, by Gary Taubes

- The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, by Thomas Kuhn

- Risk, Chance, and Causation, by Michael Bracken

- Mistakes Were Made (but not by me), by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson

- Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman

- “The Method of Multiple Working Hypotheses,” by T.C. Chamberlin

I’m looking forward to other recommendations.