In this “Ask Me Anything” (AMA) episode, Peter and Bob take a deep dive into zone 2 training. They begin with a detailed definition of zone 2 and continue by discussing the importance of adding it to your exercise regimen. They talk about how to program zone 2 training, including intensity, frequency, and duration, and metrics for tracking improvement. Additionally, they provide a detailed overview of all things related to magnesium supplementation. The two conclude with insights about how to effectively engage with your doctor in the pursuit of getting your questions answered and considerations for finding a physician that’s right for you.

If you’re not a subscriber and listening on a podcast player, you’ll only be able to hear a preview of the AMA. If you’re a subscriber, you can now listen to this full episode on your private RSS feed or on our website at the AMA #19 show notes page. If you are not a subscriber, you can learn more about the subscriber benefits here.

We discuss:

- Defining zone 2 exercise (3:30);

- The most effective ways to engage in zone 2 exercise (14:00);

- The process of training a deconditioned individual with zone 2: Dosage, frequency, and metrics to watch (19:45);

- Training for health vs. performance, and the importance dedicating training time solely to zone 2 (25:00);

- Why Peter does his zone 2 training in a fasted state (31:30);

- Improving mitochondrial density and function with zone 2 training (34:00);

- Metrics to monitor improving fitness levels from zone 2 training (36:30);

- Advice for choosing a bicycle for zone 2 exercise at home (42:30);

- Comparing the various equipment options for aerobic training: Rowing machine, treadmill, stairmaster, and more [48:15];

- Back pain and exercise, and Peter’s stability issues as a consequence of previous surgeries (51:45);

- A deep dive into magnesium supplementation, and Peter’s personal protocol (55:30);

- Advice for engaging with and questioning your doctor (1:03:15); and

- More.

Defining zone 2 exercise [3:30]

Exercise framework:

- Peter has a framework for exercise which has four components: Stability, strength, aerobic efficiency, and anaerobic performance (see AMA #7 and AMA #12)

- So when we talk about zone 2, we must understand that it is but one component

Defining zone 2 exercise:

⇒ Zone 2 exercise was covered in a previous podcast with Iñigo San Millán

- Zone 2 is defined as your highest metabolic output/work that you can sustain while keeping your lactate level below two millimole per liter (mmol/L)

- Biochemically, what’s happening as you exercise (or do anything) is the process of respiration, the process of using substrate

- We use glucose, we use fatty acids, we use oxygen, and we undergo a chemical process.

- We take the chemical energy that is stored in the bonds of those molecules and turn that into electrical energy (via the electron transport chain)

- It then gets turned back into chemical energy as we borrow from that energy to make ATP—our currency for how we do everything

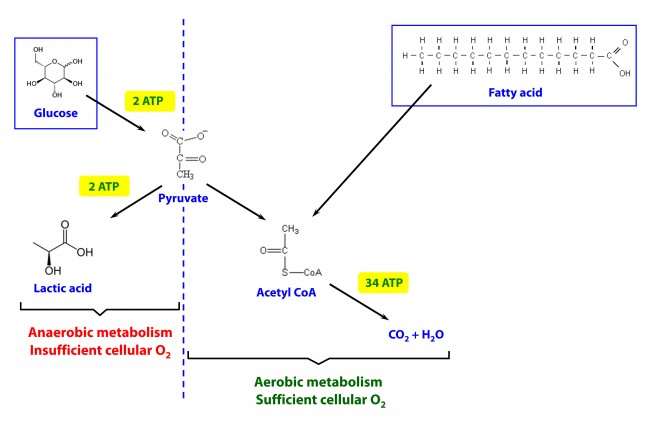

-The first step:

- Turning glucose (just using glucose in this example for simplicity) which it’s a six carbon ring, into two smaller molecules that are each made up of three carbons called pyruvate

- This step yields some energy, and costs some energy

–Step two: The body has a choice whether to:

- A) Continue this process outside of the mitochondria where I make another by-product called lactate (which can generate a little bit more ATP); Or

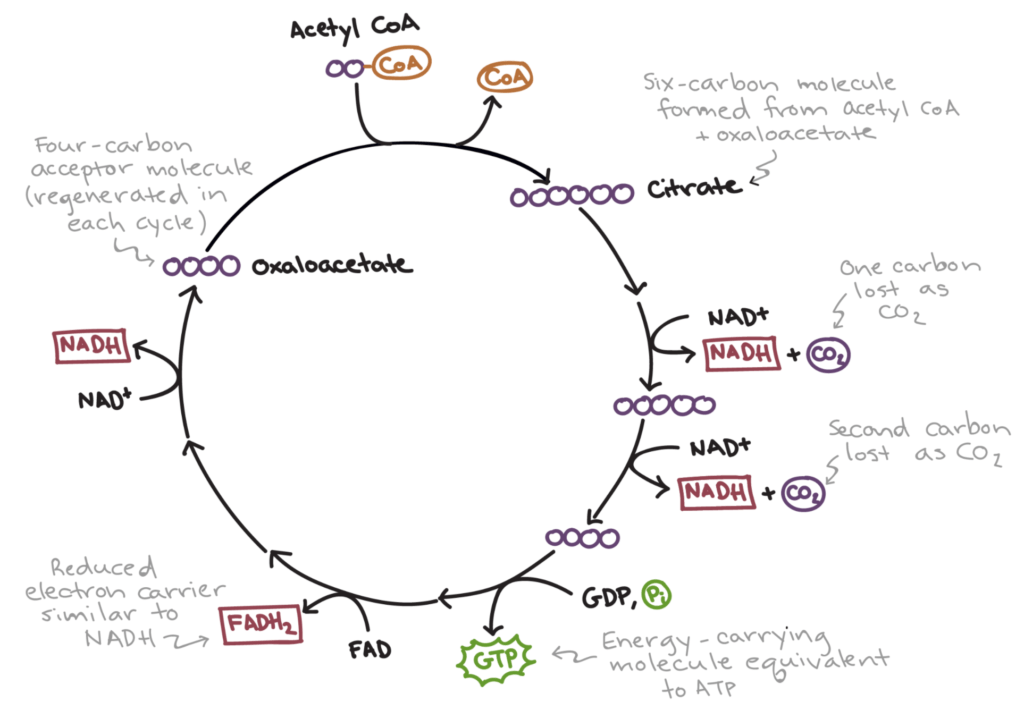

- B) Take that pyruvate and shuttle it into the mitochondria, and undergo a separate chemical pathway and a separate process called the Krebs cycle where you can make MANY more ATPs

Figure 1. ATP generation. [source]

Figure 2. Krebs Cycle. [source]

==> Krebs Cycle explained by Khan Academy here

-How does your body decide between A and B pathways to ATP?

- If you need to make ATP really quickly, you’ll take that former pathway and make lactate because you don’t need oxygen to do it—meaning you’re not limited by the amount of oxygen that is being taken up by the muscle

- If you have more time on your hands, you’ll take the latter pathway—meaning you will utilize oxygen and actually take that substrate into the mitochondria, and you will be able to make tons of ATP

What differentiates individuals…

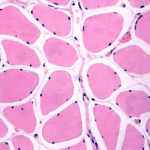

- Note: Not all people are not created equal—Both genetically, but more importantly, through training

- What differentiates the highly trained/metabolically fit from the untrained/metabolically unfit…is that ability to, under a greater and greater array of metabolic demands, make that input of substrate into the mitochondria

- Mitochondrial health then can be somewhat estimated and proxied by the ability a person has to do this

-How would you measure this?

- One of the most valuable ways to do this is to measure lactate levels

- If you start producing too much lactate, it will actually escape the muscle and get into your circulation… which can then be easily measure with a finger prick

Lactate levels at rest and during exercise

- A healthy person when they’re sitting there at rest has a lactate level of about 1.0 mmol/L

- Basic activities of daily living (walking, standing, eating) shouldn’t at all be pushing you to generate higher levels of lactate to the point that you accumulating lactate

What happens if you start doing something a little more strenuous?

- At some point, you’re going to have to start generating lactate (even the fittest person ever)

- If you need to make energy (ATP) faster than you’re able to deliver oxygen to your muscles, at some point the lactate begins to accumulate in excess of what is cleared

It’s a bit more complicated…

- The organ that is primarily responsible for clearing lactate is the liver (via gluconeogenesis), and that takes longer so there’s a big time lag there

- The other thing is that different people have different amounts at which they clear lactate from the cytoplasm of the cell—which is done via transporters called MCTs—and different people can have different levels of MCT expression

The upshot:

- The fitter a person is, the healthier a person is, the more work they can do with less lactate

- For a given individual, we use this metric of zone 2 as a place to understand

- how metabolically healthy they are;

- how good their mitochondria are; and

- how much work can be done while keeping your lactate about 1.7 to 2.0 mmol/L

⇒ For example, You could say, “My zone two is 200 watts.” And that would mean you could hold 200 watts on a bike for a very long period of time, because you’re never really going above 2.0 mmol

- 2.0 mmol/L is a very sustainable level of lactate production well below lactate threshold

- Lactate thresholds for most people is about 4.0 mmol/L

- An athlete, for context, is really only able to hold a 4.0 mmol pace for tens of minutes if not less

- And peak output is going to produce lactates easily over 10 and in some cases over 20 and those efforts can only be sustained for seconds

- You can think of zone 2 as your “all day pace”

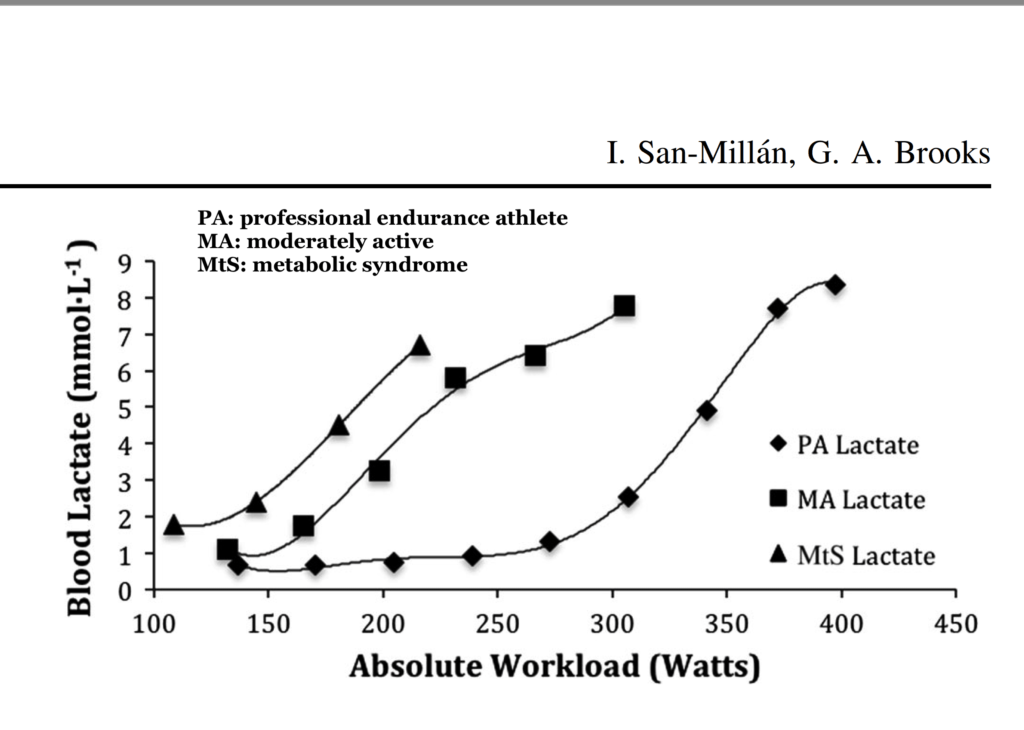

In the podcast with Iñigo San Millán…

- They discussed a study that compared 3 groups of people: i) type 2 diabetic ii) normal fit people, and iii) to world-class athletes (cyclists)

- The difference in the amount of power that the athletes could put out on a bicycle while keeping lactate at 2.0 mmol/L was staggering — Especially once you normalize for weight and you get how many watts per kilos

Figure 3. Image credit: (Brooks and Millan, 2018)

The most effective ways to engage in zone 2 exercise [14:00]

Machines for doing zone 2 exercise:

{end of show notes preview}

Is there a lactate level that is a minimum in order to get zone 2 results? I.E. is 1.5-1.75 mmol/l enough to get a good zone 2 effect or do you have to push 2.0 in order to get a good effect? On the other hand, if you end a ride at 2.1-2.3 mmol, have you lost all good mitochondrial effects?

I also have this question!

Any chance if a comparison between Zone 2 training and MAF training as promoted by Dr Maffetone? Thanks.

I had a similar question. How does the lactate criterion compare to using a heart rate criterion for determining if one is in zone 2? The heart rate criterion I’m thinking of being the HR=(180-Age) formula.

I would like to see understand the differences between these two as well. Thank you.

I’m not a subscriber, so did not listen to the whole podcast, nor see the full show notes. But I recently read a 2018 paper about the challenges with measuring magnesium levels. In case any reader is interested, here are info and links. (and Figure 6, down a few pages in the paper, is a good illustration of magnesium processing and where stored)

“Challenges in the Diagnosis of Magnesium Status”

Jayme L. Workinger, Robert. P. Doyle, and Jonathan Bortz

Nutrients. 2018 Sep.

web page: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6163803/

PDF: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6163803/pdf/nutrients-10-01202.pdf

As a rock climber I am very interested in the factors involved in avoiding anaerobic atp production in individual muscles where the bottle neck may not be oxygen production and lactate clearing by th eiver, but rather the inability to get the oxygen into the muscle cells. I.e. You may not even be breathing very hard, but the forearm muscles are lacking oxygen. What factors can affect the ability to get oxygen to the muscles. Or am I geting this wrong?

Peter,

As a new Peloton user for the last number of months I periodically re-do my 20 minute Functional Threshold Power (FTP) test so I can monitor which zone (using watts) I am working in. Given that I also get real time heart rate data, how would you recommend I prioritize these metrics when doing zone 2 work (ie Zone 2 predicted wattage based on FTP vs heart rate zone 2 / Maximum Aerobic Function (MAF) heart rate).

Better to split the difference and just be mindful of both?

This was a great AMA. Thanks again.

Another excellent podcast – thank you. Just a note though about being a customer and finding another doctor. For many of us, depending on location and age, just finding ANY doctor taking new patients can be challenging. I finally found a provider who was accepting new patients – she was as ARNP as there were no MDs/DOs/NDs available etc. I saw her once for about 10 minutes intake and next time I called, she’d left the area. I’m on Medicare with Medicare Advantage insurance. I’d be happy to do telemedicine but doesn’t seem to work if you need bloodwork or vitals or local specialist referrals.

Can you recommend a good (not too expensive) lactate meter for home use? Thanks! (I looked thru some of the notes but could not find any hints so far).

I was also looking for the answer to this question. Thx

Great answer to questions I had on zone 2 inside my rides, completely agree on kieser/peleton/trainer ratings. On back pain- I have found this 12 minute daily exercise helpful in rounding out my back strength with core and reducing pain on the bike and from some residual reactive arthritis.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4BOTvaRaDjI

Which lactate meter do you use? Please let us know!

Did I get this right? Pin prick to get lactate levels is not just to get a baseline read on things, but is done multiple times to monitor each training Zone 2 session, several times a week? Just incredible. I can understand this being the case in a research lab on exercise, but wouldn’t fly with most people. Would lactate levels correspond with exertion, and hence other measures of exertion, such as heart rate? I just listened to the MAF podcast, and there is something arbitrary about 180-age being such a uniquely useful value. Except perhaps if it’s an approximation of certain metabolic truths as understood by Inigo San Millan. I currently measure my exertion using a Polar H7 monitor, plugging in a HR Max generated by a formula from CERG team of Norwegian University of Science and Technology. It’ll have to do. Sorry, daily pin pricks ain’t happening.

Figure 11 in the San Millan episode has an interesting graph of power vs lactate and heart rate. Heart rate seems linearly correlated to pure wattage, fulfilling a raw need for oxygenated blood. Lactate levels, on the other hand, can remain flat for extended periods of low power exertion, and the fitter one is, the more so. So to answer my own question, it may not be wise to approximate blood lactate levels with a Polar heart rate monitor. The lactate level patterns during exercise may cluster similarly in average healthy adults. But Zone 2 would be especially in flux and difficult to guess at the extreme ends, in a diabetic or aspiring serious athlete respectively.

What can I reliably do to test whether I am in Zone 2? Is there a way to (reliably) use heart rate only? Or do I have to combine it with lactate measurements (at least for some time)? If so, is there a device for lactate testing that you can recommend?

FYI to those who asked about a lactate meter, I see in AMA #12 Peter recommended Lactate Plus Meter by Nova.

I keep coming across articles mentioning the NASA study (1980) about rebounding and how it benefits the body more than running on a treadmill.

Do you have an opinion on the issue?

Peter, I have been doing a deep dive into magnesium recently. I haven’t heard you talk about magnesium bisglycinate at all. I take thorne’s magnesium bisglycinate and am wondering how it differs from the other forms of magnesium you talk about.

I followed the link presented here to magtein.com. I put in an order on January 21 and my credit card was charged. I received an email with the USPS tracking information. Following this tracking information, it appears the product was never shipped. Now, on March 7, I cannot even connect to the magtein.com website. I will be following up with my credit card company. Buyer beware!

A follow up on my comment:

I was finally able to get through to the Magtein website to notify them that they had charged my credit card and had not shipped the product. A few days later I received my order. After six weeks of waiting with no correspondence, I was a bit disappointed that there was no note of apology, but I am relieved to finally get the product.

Ron Tugnutt aka the Ottawa Senators goalie from 96-00?

When alter your magnesium protocol based on wether you are fasting or not, is that based on intermittent fasting or prolonged.