When it comes to clinical research, systematic reviews and meta-analyses are often extolled as the pinnacle of evidentiary rigor and reliability. In reviewing information from multiple randomized clinical trials, they’re considered stronger than any single study in isolation. But not all reviews and meta-analyses are created equal, and even “correctly” done analyses – such as those including only data from rigorous trials – have the potential to be misleading. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis on hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and breast cancer recurrence provides an example of precisely this problem, reporting conclusions that are not as robust as they might first appear.

HRT & Breast Cancer

Before we tackle the issues with this study, let’s first back up and discuss what motivated the authors to conduct it.

As women approach menopause, they experience a dramatic, rapid drop-off in levels of sex hormones, in contrast to the slow age-related decline experienced by men. Estrogen drops to 1% of pre-menopause levels, leading to vasomotor symptoms (e.g., hot flashes, night sweats), decreased bone mineral density and muscle strength, vaginal atrophy, and a host of other, often long-term effects with significant impact on one’s quality of life.

HRT is hands-down the most effective treatment available for alleviating these symptoms and was the standard of care until 2002, when the first published results from the Women’s Health initiative (WHI) raised concerns about increased breast cancer risk. However, the difference between groups did not reach statistical significance – i.e., a level that could sufficiently eliminate the possibility that it was simply attributable to chance variation. Further, the results indicated a relative risk for breast cancer of only 1.26 – a review of these data puts that risk on par with eating 1 additional serving of french fries per week or eating grapefruit. (For more on this topic, check out my conversation with Drs. Avrum Bluming and Carol Tavris in episode #42 of The Drive, as well as my recent chat with Andrew Huberman on menopause and HRT. Additionally, keep and eye out for an upcoming podcast episode with Dr. JoAnn Manson, a principal investigator for the Women’s Health Initiative.)

Nevertheless, a link between HRT and breast cancer is plausible mechanistically, given the known links between hormones and breast cell proliferation. Since HRT is comprised of estrogen or a combination of estrogen plus progesterone, the association between hormones and cell proliferation underlies the concern that HRT may contribute to cancer formation or recurrence, especially for survivors of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer – a form of breast cancer in which the cancer cells express receptors for estrogen and progesterone.

About the Analysis

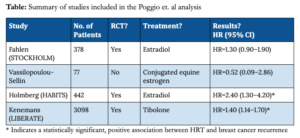

Given these concerns, Francesca Poggio and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the risk of breast cancer recurrence following HRT in breast cancer survivors. By examining four studies, the authors concluded that HRT increases the chance of breast cancer recurrence (HR=1.46, 95% CI = 1.12-1.91). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are supposed to be the strongest possible levels of evidence in biomedical science, so should we take Poggio et al.’s conclusions as fact?

Critiques of the Study

Certainly not, judging by the swift criticism of this analysis from experts in the field. After the Poggio et al. study was published, Dr. Bluming wrote a letter to the editor that appeared in the journal’s very next issue, explaining deficiencies of Poggio’s analysis. Bluming points out that, among the very small number of studies included in the analysis, only two were prospective, randomized studies investigating traditional HRT (i.e., using estrogen or estradiol). A third randomized HRT study does exist, but the authors omitted it from their review and analysis, though they instead included a prospective cohort study which had originally been designed as randomized. Bluming notes that only one of these three included studies had identified a statistically significant positive association between HRT and breast cancer risk, as shown in the summary table below. If the meta-analysis had been limited only to these three (the STOCKHOLM trial, Vassilopoulou-Sellin, and the HABITS trial), breast cancer recurrence rates between HRT and control groups are not significantly different.

This brings us to the fourth and final study in the analysis. When including this fourth study, Poggio et al. did indeed observe significant differences in breast cancer recurrence between treatment and control groups, but as Bluming points out, the treatment in this additional study was not traditional HRT. Instead of estrogen, patients were treated with the synthetic hormone tibolone, a drug with weak estrogenic, progestogenic, and androgenic activity. (I have always been wary of synthetic hormones and, as I have discussed many times before, have always suspected that the synthetic progestin (MPA) used in the WHI may have indeed accounted for the difference in breast cancer rates between women taking only estrogen (i.e., those without a uterus) and those taking estrogen plus MPA.)

Not all meta-analyses are created equal

Back in my AMA #30 discussion of the so-called “hierarchy” in quality of evidence, I explained that while meta-analyses certainly can be better than any single study in isolation, it isn’t necessarily true. A meta-analysis can be no better than the studies which comprise it. My mentor’s words from the lab still resonate, “a hundred sow’s ears make not a pearl necklace.” Determining the value of a meta-analysis is far more than a matter of counting the studies included or even assessing their quality, and the analysis by Poggio et al. is a perfect illustration. We must also consider the strategies employed in selecting those studies.

So let’s take a look at a few common study selection pitfalls in meta-analyses and consider how the Poggio et al. analysis stacks up.

1. Inclusion criteria are overly strict.

The authors state that their criteria for including studies in their analysis required that studies be English-language RCTs studying HRT in pools of adult patients, including breast cancer survivors. Only four trials met these criteria, and because the authors further limited their analysis to publications reporting results in terms of hazard ratios, one of these four studies was omitted. (Notably, this study had found no link between HRT and cancer recurrence.)

2. Inclusion criteria are not strict enough.

While Poggio et al.’s inclusion criteria were fairly strict in some ways, they were not strict enough in others. By including a trial using tibolone, a non-traditional HRT treatment with no clear estrogenic effect in the breast, the authors lumped together studies with dissimilar research questions: one addressing the effects of tibolone, and the others addressing the effects of estrogen or estrogen + progesterone. By grouping together apples and oranges, they obscure the potentially unique effects of different HRT compounds. This potential muddying effect is of particular concern when we consider that the tibolone study provided 77.5% of all subjects included in the meta-analysis, and that a significant difference in breast cancer recurrence is not found without inclusion of this study. Further, since tibolone is not approved for use in the U.S., inclusion of this study undermines the clinical relevance of the meta-analysis to American women.

3. Results from included studies are too heterogeneous.

The strength of a meta-analysis is undermined not only from high heterogeneity in study design (see point #2 above), but also from high heterogeneity in study results. A meta-analysis takes results from several studies and translates them into a single, combined value. If the studies generally agreed in their findings (e.g., all had found positive effects with roughly similar effect sizes), then pooling results in a meta-analysis can add accuracy and reliability by effectively increasing the sample size. If, however, the various studies exhibit inconsistency, then a meta-analysis can mask such variance, generating a summary result which doesn’t accurately reflect any of the studies in question or take into account potentially critical causes of variance.

The Poggio et al. analysis included two studies that found no difference in breast cancer recurrence between HRT-treated participants and controls, and two studies that did find a significant difference. Though the authors applied a statistical test for heterogeneity which yielded negative results (indicating a lack of heterogeneity), these tests tend to be underpowered when applied to such a small number of studies, and the fact that omitting the tibolone trial would have changed the net result raises questions about whether these studies were truly homogenous enough for meaningful pooling.

Take-home message

In AMA #30, I discussed how the quality of a meta-analysis depends on the quality of the studies it includes: “garbage in, garbage out.” But the dangers don’t end there – we must also look closely at how those studies have been selected. In examining the association between HRT and breast cancer recurrence, Poggio et al. sought to include only studies with the “gold standard” RCT design, yet they failed to ensure that all included studies were addressing the same question. Methodological differences across studies may have contributed to their apparent inconsistency in results, but rather than analyze those differences and their varied effects, the authors obscured them with their overly-generalized summary result.

So what can we learn from this study? Very little about HRT and breast cancer, I’m afraid. But perhaps an important lesson about meta-analyses: “garbage in” isn’t the only way to wind up with “garbage out.” Whether you start with poor ingredients or the very best, if you put them together incorrectly, the result will likely end up in the trash.

For a list of all previous weekly emails, click here.