Still keeping up your New Year’s resolutions to make it to the gym every day and eat healthful food? Congratulations, you have officially made it past “Fall Off the Wagon Day.” Defined as the second Saturday in February, it is the date on which, according to analyses of gym attendance and fast-food sales, most people tend to give up on their resolutions.

Of course, giving up a resolution doesn’t generally involve a sudden loss of interest in fitness and health. The long-term goals stay the same – the change lies instead in the day-to-day choices affecting whether or not we achieve those goals. The impulse donut purchase with your morning coffee order. Skipping the gym after a long workday. A late-night Netflix binge despite early meetings the next morning. For all of these decisions, we balance a desire for immediate gratification against what’s best for us in the future. We often make these sorts of choices with complete awareness of this trade-off. We know that regret is soon to come – that moment when we step on a scale or see the bags under our eyes and proceed to beat ourselves up over the short-sightedness of our choices.

If this routine sounds familiar, you certainly aren’t alone. But it raises the question: why? Why is it so difficult to make choices that we know will be best for us in the long run?

Because we have a hard-wired bias for the immediate. Given a choice between a reward now or a reward in the future, humans tend to choose the present, even when they know the future reward would be substantially larger. It’s a phenomenon of behavioral economics known as “hyperbolic discounting” – in our minds, we discount the value of the future reward. And the greater the delay, the greater the discount. As a simple example, let’s say you were offered the choice of $900 today or $1000 tomorrow. Classical experiments tell us that most people would choose $1000 tomorrow, but if the delay were extended to say, two months, most would instead opt for the smaller, immediate payout. In other words, as the time delay to a reward increases, our perceived value of that reward decreases.

Exponential vs. Hyperbolic Discounting: A Matter of Time

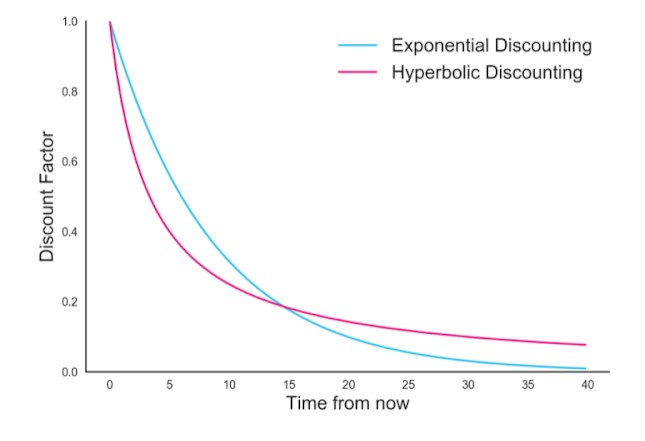

On some level, placing a higher value on immediate rewards makes sense – money acquired now, for example, could be invested and earn interest, achieving a higher value over the delay period associated with the future reward. We would expect that for a given set of reward options separated by a fixed time interval, our rate of discounting would remain fairly consistent over time – the difference between $10 today and $20 tomorrow is the same as the difference between $10 in one year and $20 in one year and one day. That is to say, discounting is expected to follow an exponential curve as a function of time.

Yet observations of human behavior consistently show that this is not the case. The term “hyperbolic discounting” refers to the fact that discount rates follow a hyperbolic curve, meaning that a comparison between two points depends not only on the time interval between them, but also on how distant the two points happen to be from the present (Figure 1). In other words, hyperbolic discounting is inconsistent across time: the difference in discounting between a present reward and a future reward is great, but the difference in discounting between a future reward and reward that is further in the future is tiny. Take our money example from earlier. Most people would choose $900 today over $1000 in two months, but if it were instead a choice between $900 in one year and $1000 in one year and two months, our preference shifts back toward the $1000 prize.

Figure 1: Comparison of exponential (time-consistent) discounting and hyperbolic (time-inconsistent) discounting. [Source]

Hyperbolic Discounting Was Once Adaptive

Seems illogical, doesn’t it? Well, yes – hyperbolic discounting is an example of a “cognitive bias”: a subconscious, hard-wired error in processing and interpreting information which causes deviations from rational decision-making. But like many other cognitive biases, hyperbolic discounting is an adaptation which provided benefits to humans over the course of evolution – for instance, by prioritizing immediate survival (ex/ eat the abandoned, sickly buffalo) over less certain long-term gains (ex/ track the herd and kill several of the largest animals). An immediate reward is a sure thing, while a future reward leaves space for problems to arise (ex/ starvation, death) which prevent acquisition of the larger prize. The longer the delay to a pay-off, the higher the risk that it might never happen.

Or so it was for our ancestors. In a modern setting, this bias toward immediate reward is often maladaptive and underlies a tendency toward impulsivity. Long-term goals of fat loss or retirement savings are at an inherent disadvantage when weighed against an extravagant dinner with a hefty bar tab this weekend. Individual variation in hyperbolic discounting has also been proposed as a risk factor for developing addictions, as smokers and problem gamblers have been shown to have steeper discounting rates for future monetary rewards compared to controls.

Counteracting Our Bias for Immediate Gratification

All of this may paint a pretty bleak picture, but by recognizing our inherent preference for immediate pay-offs, we can begin to develop strategies to counteract hyperbolic discounting – or even use it to our advantage. Although we can’t change the hardwiring that causes the mental process of hyperbolic discounting, we can mitigate the effects that devaluation of the future ultimately has on the decisions we make.

Steep discounting of future rewards leads to impulsive behavior, and reducing or eliminating the opportunity to act impulsively is thus an effective strategy for avoiding bad choices caused by a bias toward instant gratification. One well-established strategy for reducing impulsivity is precommitment, which takes advantage of the time-inconsistency of hyperbolic discounting. When comparing two rewards that are far in the future, they are discounted nearly equally, so by making a decision in advance, we are less biased by the present and can more accurately compare the relative values of various options. Thus, to have the best shot of reaching our long-term goals, we can lock ourselves into good decisions, making it more difficult to bow to immediate temptations when the time comes. Pay in advance for a month’s worth of HIIT classes. Plan a week’s worth of meals and only buy ingredients necessary for those meals. Find a gym buddy and keep each other accountable for a fitness schedule. Or as I discussed in my Thanksgiving newsletter, get leftover dessert out of the house.

Using Hyperbolic Discounting to Our Advantage

We can also use hyperbolic discounting to our advantage by breaking down long-term goals into a series of small, short-term goals. Instead of telling yourself that you want to increase your deadlift by 100 lbs, set a smaller, incremental goal that offers a quicker sense of accomplishment. Once achieved, repeat with another increment, then another, and another, never thinking about the daunting long-term goal until it’s right in front of you.

In a similar way, we can hack hyperbolic discounting by creating more immediate rewards for ourselves when we make the right choices for distant goals. A colleague of mine once mentioned that she helped herself save money during graduate school in New York City by creating small rewards for certain thrifty decisions. If she skipped ordering wine at dinner with friends or resisted temptation to take taxis instead of the subway, 20% of the saved money would go to a “weekend getaway fund.” (From the sound of it, she ended up having quite a few weekend getaways.) The same strategy can be applied to goals related to long-term health – just be sure to choose rewards that don’t completely undercut the benefits from those good choices.

The bottom line.

So where does this leave us? If you are one of the many who has “fallen off the wagon” on your New Year’s resolutions, don’t sweat it – today is as good a day as any other for getting back on track. But as you resume your commitment toward improving your health and well-being, keep in mind that it’s a journey made of many small decisions along the way. Yes, for each of these choices, we may be biased toward immediate gratification, but by recognizing this, we can prepare for it and outfox our own error-prone minds.