As some of you may recall from my conversation with Rick Johnson, high levels of circulating uric acid have been linked with a number of health concerns and serve as a biomarker for inflammation, metabolic syndrome, and hypertension.

Blood-based biomarkers are advantageous for their ease of frequent measurement, as the cost of a blood draw is relatively low. However, certain biomarkers can be misleading if they are subject to transient fluctuations. For instance, a single bout of carbohydrate intake causes an acute spike in blood glucose without any long-term effect on glucose metabolism, which is why glucose measurements are typically done first thing in the morning in a fasted state. This way, each reading isn’t confounded by when or what you ate that morning, allowing meaningful assessment of trends in the longitudinal data.

Likewise, while consistently elevated levels of circulating uric acid are associated with chronic disease risk, this biomarker is also subject to misleading measurements caused by transient elevations. A number of factors may trigger a rise in uric acid, but interpreting uric acid levels requires an awareness of whether these increases are chronic or acute. Diet, for instance, can influence circulating levels both in the short-term, as in the case of my ketogenic diet-induced uric acid elevation discussed in AMA 44, and long-term, as with decades of high-fructose diets. But how does exercise impact serum uric acid?

How does exercise raise uric acid?

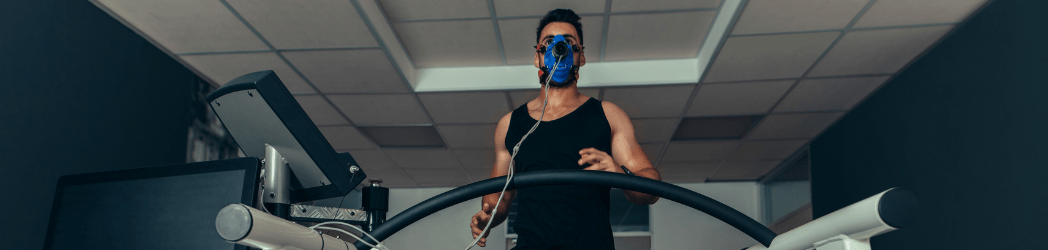

During very intense bouts of exercise, the skeletal muscle energy requirements exceed the energy production capacity of aerobic metabolism. In this state, known as “supramaximal exercise,” the muscle relies more heavily on anaerobic metabolism, a far less efficient pathway in producing energy in the form of ATP. Thus, as the muscle continues to use ATP for energy and anaerobic metabolism is unable to replenish it, muscle ATP levels become depleted by as much as 30-40%. This depletion, along with the build-up of products from ATP degradation, activates an enzymatic pathway that converts those degradation products into inosine-5’-monophosphate (IMP) and, through a series of additional steps, into uric acid.

After short-duration exercise, the sum amount of ATP and its degradation products (ADP and AMP) usually return to pre-exercise levels in less than an hour, as do IMP levels. However, during repeated bouts of supramaximal exercise to the point of failure, IMP degradation is significant, which causes larger shifts in metabolite concentrations and progressively increases serum uric acid.

A study from the 1980s demonstrated these effects of supramaximal exercise in a group of untrained, but active, young, adult men (“supramaximal group”). The researchers found that supramaximal exercise raised serum uric acid over three days of repeated supramaximal interval training (120% VO2 max for 1 minute followed by 4 mins recovery repeated 24 times or until failure–just imagine how much fun this was!). This group started with normal baseline uric acid levels (5.9 ±0.7 mg/dL). By the midpoint of the exercise bout, their serum uric acid had increased to 7.6 ±1.9 mg/dL and progressively rose to 8.3 ±0.6 mg/dL post-exercise. On day 2, starting levels remained elevated and progressively rose to a high of 9.8 ±2.0 mg/dL post-exercise.

Does all exercise raise uric acid?

When energy expenditure exceeds the readily available ideal sources, temporary shifts in metabolism must occur, leading to a rise in uric acid. But does exercise also raise uric acid if it doesn’t exceed aerobic capacity and deplete ATP?

In the study described above, a different group of young men (“submaximal group”) underwent three days of continuous training for two hours at 65% VO2 max (similar to Zone 2) and showed no difference in serum uric acid before, during, or after exercise on any of the three days (average uric acid of 5.6 ±0.8 mg/dL). Even though the continuous training involved greater overall work output (i.e., higher total MET-hrs), the submaximal group remained in an aerobic metabolic state and could oxidize glucose and fatty acids for a continuous energy supply. In contrast, the high-intensity exercise performed by the supramaximal group exceeded the locally available energy sources, leading to decreases in ATP stores and an increase in IMP breakdown to uric acid, resulting in temporary hyperuricemia.

Is exercise-induced hyperuricemia a cause for concern?

The post-exercise serum uric acid level in the supramaximal group would be alarming if viewed in isolation, as the participants far exceeded the threshold that defines hyperuricemia for men: uric acid levels of 7 mg/dL (women have a lower threshold of 6 mg/dL). But it’s important to recognize that the elevation of uric acid induced by exercise was transient.

Even in this 3-day study in untrained subjects, we see hints of the human body’s capacity to adapt to stressors to maintain homeostasis. By day 3 of the exercise protocol, both pre-and post-exercise levels, 6.9 ±1.3 and 7.8 ±1.5 mg/dL, respectively, were lower than the pre- and post-exercise measurements on day 2. Although still elevated over baseline, these numbers indicate that serum uric acid may eventually return to normal levels even if daily high-intensity exercise were to be continued, perhaps reflecting a reduction in the degree of ATP depletion in response to supramaximal exercise.

The bottom line

When using uric acid measurements as a metric of health status and chronic disease risk, it’s critical to understand what factors might alter those measurements. Supramaximal exercise results in a temporary rise in uric acid, while moderate intensity exercise does not. (I am pretty sure this phenomenon explains my sky-high uric acid levels between 2011 and 2014 when I was on a ketogenic diet, which raises uric acid due to impaired clearance, and doing submaximal efforts in cycling and swimming on a nearly daily basis.)

Still, possible elevation in serum uric acid should not be a reason to forgo supramaximal training. Unless you already have pathologic uric acid levels, the transient rise is not harmful. Indeed, uric acid is the predominant antioxidant molecule in plasma, and some research suggests that the acute elevation of circulating uric acid is actually protective against the oxidative damage of high-intensity exercise. So while chronically elevated uric acid is a biomarker for chronic disease, transient elevation is not a cause for alarm and may even be one of the body’s built-in forms of protection against oxidative damage.

For a list of all previous weekly emails, click here.