You’ll recall from last week’s post I did a self-experiment to see if I could learn something about the interplay of exercise and ketosis, at least in myself. To understand this discussion, you’ll want to have read Part I of this post.

However, before getting to this, I want to digress and briefly address two unrelated issues:

- Some of you (about 67 or 68 as of this writing) have sent me various links to news reports released yesterday reporting on a study out of Harvard’s School of Public Health. I was planning to eventually write a post about how observational epidemiology is effectively at the heart of the nutritional crises we face – virtually every nutrition-based recommendation (e.g., eat fiber, don’t eat fat, salt is bad for you, red meat is bad for you) we hear is based on this sort of work. Given this study, and the press it’s getting, I will be writing the post on observational epidemiology next week. However, I’m going to ask you all to undertake a little “homework assignment.” Before next week I would suggest you read this article by Gary Taubes from the New York Times Magazine in 2007 which deals with this exact problem.

- I confirmed this week that someone (i.e., me) can actually eat too much of my wife’s ice cream (recipe already posted here –pretty please with lard on top no more requests for it). On two consecutive nights I ate about 4 or 5 bowls of the stuff. Holy cow did I feel like hell for a few hours. The amazing part is that I did this on two consecutive nights. Talk about addictive potential. Don’t say I didn’t warn you…

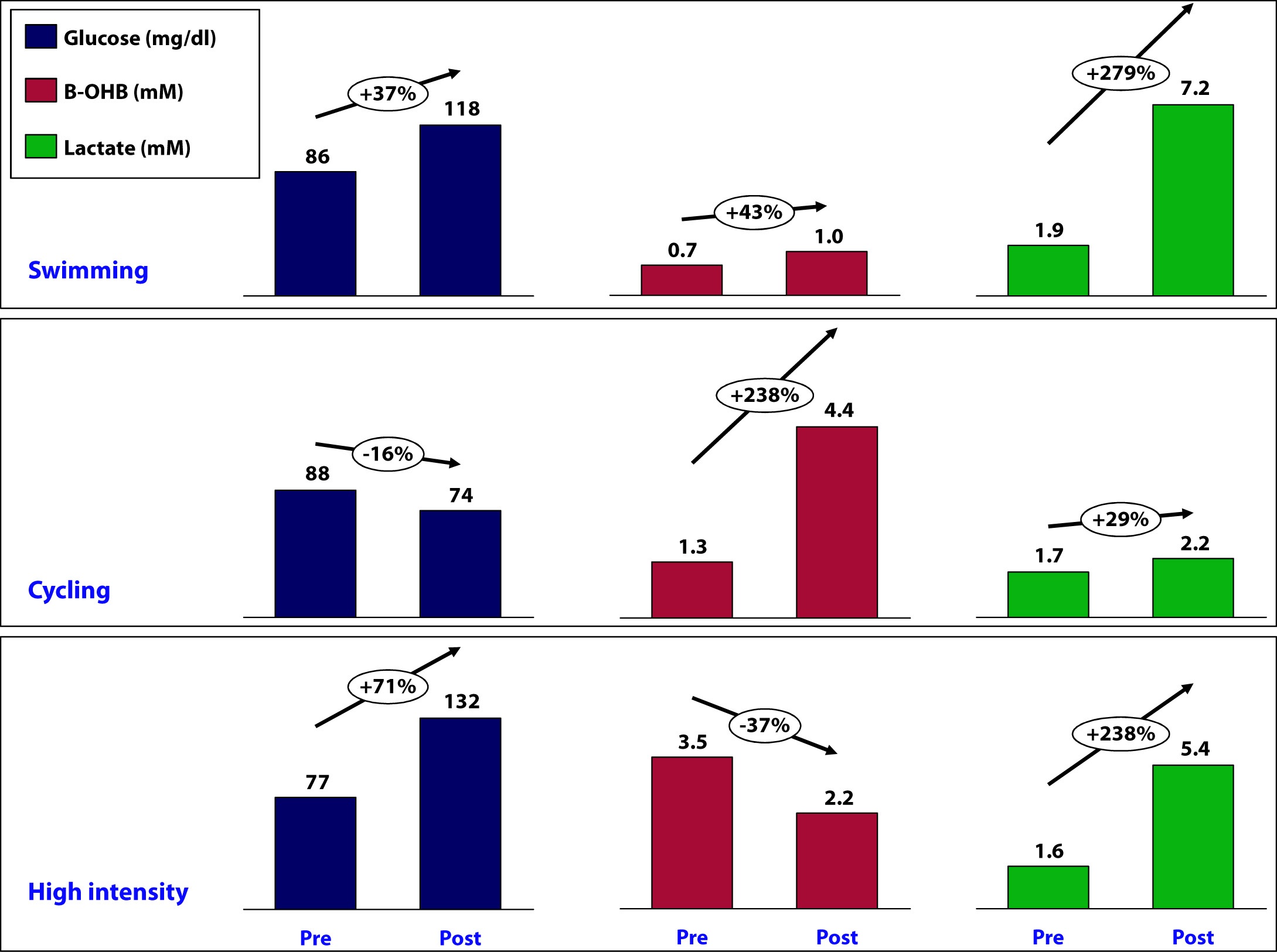

OK, back to the purpose of this post: How is ketosis impacting my ability to exercise? Here is the summary of the results from my personal experiment:

Let’s take a closer look at what may have been going on in each workout and see what we can learn.

Swimming

This workout probably produced the most lactate of the three workouts (we don’t know for sure because I only measured immediate pre- and post- levels without measuring in-workout levels). My glucose level rose by nearly 40% during this workout despite the fact that I did not consume anything.

How does this happen? Our bodies store glucose in the liver and in muscles in a “storage” form (a long chain of joined glucose molecules) called glycogen.

Whenever our bodies cannot access sufficient cellular oxygen, our metabolism shifts to a less efficient form of energy acquisition called anaerobic catabolism. During these periods of activity, we cannot oxidize fat or glycogen (i.e., use oxygen to harness the full chemical potential of fat or carbohydrate molecules). I will be writing in much more detail about these ideas in the next month or so, so don’t worry if these ideas seem a bit foreign right now. Just know that sometimes our bodies can convert fat or glucose to energy (efficiently), and sometimes we can only convert glucose to energy (inefficiently).

Because of my ketosis, and the metabolic flexibility that accompanies it, I only “require” that my body turn to glucose for energy under the most “stressful” forms of exercise – like I was doing a lot of during this workout. But keep in mind, my muscles CANNOT export one gram of the glucose they store, so any glucose in my bloodstream is either ingested (which I didn’t do) or coming from my liver, which CAN export glucose.

Furthermore, the stress of a workout like this results in my adrenal glands releasing a set of chemicals called catecholamines, which cause my liver to export even more of its stored glucose via a process called hepatic glucose output (HGO).

[As an aside, one of the major defects in type-2 diabetes is the inability of insulin to suppress HGO. In other words, even when not under the catecholamine stress that “should” lead to HGO, their livers constantly export glucose, which contributes to elevated blood glucose levels. The very popular drug, metformin, used often in type-2 diabetes, blocks this process.]

While I did experience a pretty large rise in lactate (almost 3x), my ketones still went up a bit. This could imply a few things:

- Elevated lactate levels do not directly inhibit beta-hydroxybutyrate (B-OHB)

- Mild elevations in glucose do not directly inhibit B-OHB

- Mild elevations in glucose do not directly inhibit B-OHB, if insulin is being suppressed (as is the case during vigorous exercise)

- B-OHB was suppressed, but we are only appreciating the net effect, which was a small increase (i.e., because of my MCT oil and activity, B-OHB levels were rising dramatically, but the rise was blunted by some other factor, such as HGO, insulin, and/or lactate)

More questions than answers from this workout, so on to the next workout.

Cycling

Despite this being a tough ride at several points, on average it was less stressful than the other two workouts and I spent the greater fraction of time in my aerobic to tempo (zone 2 to zone 3) zones.

A ride like this, however, is a great example of the advantages of improved metabolic flexibility that accompanies nutritional ketosis. My average heart rate during this 6 hour ride was 141. Prior to becoming ketotic, at a HR of 141 my respiratory quotient (RQ) was about 0.98, which meant I was almost 100% dependent on glycogen (glucose) for energy. Today, at a HR of 141 (with the same power output), my RQ is about 0.7 to 0.75, which means at the same HR and same power output as prior to ketosis, I now rely on glycogen for only about 10% of my energy needs, and the remaining 90% comes from access to my internal fat stores.

This is an important point. I will devote future posts to this topic in more detail, but I wanted to use this opportunity to mention it.

So what happened physiologically on this ride?

- My glucose levels fell, probably because I was slowly accessing glycogen stores for peak efforts (once my HR reaches 162 I become 50% dependent on glycogen) throughout the ride (e.g., peak climbing efforts, hard sections on flats), but my liver was not “called on” to dump out a massive amount of glucose in response to a catecholamine surge (and if it was, at some point during the ride, that amount of glucose had been used up by the time I was finished).

- B-OHB levels increased by about 2.5x – to 4.4. mM, which is pretty high for me. My highest recorded B-OHB level was 5.1 mM (also after a long ride). This confirms what my RQ data indicate — my body almost entirely relies on fat oxidation for energy for activity at this intensity. In the process, B-OHB is generated in large quantities, both for my brain and also my skeletal muscles (e.g., leg muscles). In reality, cardiac myocytes (heart muscle cells) also “like” B-OHB more than glucose and probably also access it when it is abundant.

- Lactate levels by the end of the ride were effectively unchanged though. Based on “feel,” I suspect I hit peak lactate levels of 8 to 10 mM on this ride during peak efforts, but I had ample time to clear it.

A few observations:

- I consumed 67 gm of carbohydrate on this ride (of which 50 gm was Generation UCAN’s super starch), yet this did not appear to negatively impact my ability to generate ketones. Technically, we can’t be sure this is the case, since I would have needed a “control” to know this (e.g., my metabolic and genetic twin doing and eating everything the same as I did, but without the consumption of super starch and/or without the bike ride). It’s possible that super starch did slightly inhibit ketosis and that my B-OHB level would have been, say, 5.0 mM instead of 4.4 mM. Metabolic studies of super starch show that it has a minimal impact on insulin secretion and blood glucose levels, hence the name “super” starch.

- Whatever impact peak levels of lactate production and hepatic glucose output had during the ride, they seem blunted by the end of the ride (and the ride did finish with a modestly difficult 1.4 mile climb at 6-7% grade, which I rode at a HR of about 150).

Since neither lactate levels nor glucose levels (nor insulin levels by extension) were elevated, I can’t really draw any conclusion about whether one factor, more than any other, suppressed production of B-OHB, so on to the next workout.

High intensity training

This sort of workout spans the creatine-phosphate (CP) system and the anaerobic energy system, and probably involves the aerobic energy system the least. I’ll write a lot about these later, but for now just know the CP system is good for very short bursts of energy (say 10-20 seconds) and recall the previous discussion of aerobic and anaerobic catabolism. In other words, this is the type of workout where my nutritional state of ketosis offers the least advantage.

- This workout saw the greatest increase in glucose level, about 70%. It is important to recall that during this workout I ingested water with a small amount of branched chain amino acids (BCAA’s – valine, leucine, isoleucine) and super starch, about 4 gm and 10 gm, respectively. I do not believe either accounted for the sharp rise in blood glucose and, again, I believe hepatic glucose output in response to a strong catecholamine surge attributed to this increase.

- Lactate levels also rose, though probably less so than during a peak swim effort. This suggests more of the effort in this workout was fueled by the CP system (versus the anaerobic system, which probably played a larger role in the swim workout).

- This was the only workout that saw a fall in B-OHB levels, which now offers some insight into what might be impacting B-OHB production.

Contrasting this workout with the swim workout draws a pleasant contrast: both saw a similar rise in lactate, but one saw twice the rise in blood glucose. In the former, B-OHB was unchanged (actually rose slightly), while in the latter, B-OHB fell by over a third.

This suggests – but certainly does not prove – that it is not lactate per se that inhibits ketone (B-OHB) production, but rather glucose and/or insulin. It is possible the BCAA played a role, and if I was thinking straight, I would not have consumed anything during this workout to remove variables. But I have a very hard time believing 3 or 4 gm of BCAA could suppress B-OHB. When you see hoof prints in the sand, you should probably think of horses before you think of zebras.

Conversely, there is some evidence that lactate promotes re-esterification of fatty acids into triglycerides within adipose cells. What does that mean in English? High levels of lactate take free fatty acids and help promote putting them back into storage form. This would prevent free fatty acids from making their way to the liver where they could be turned into ketones (e.g., B-OHB). In other words, we may be missing this effect because of my sampling error – I only sampled twice per workout, rather than multiple times throughout the workout.

So what did I learn, overall?

I think it’s safe to say I did not definitively answer any questions, which is not surprising given the number of confounding factors, lack of controls, and sample size of one. However, I think I did learn a few things.

Lesson 1

The metabolic advantages of nutritional ketosis seemed most apparent during my bike ride, evidenced by my ability to access internal fat stores across a much broader range of physiologic stress than a non-ketotic individual. (More on this in Lesson 4.)

Lesson 2

The swim and high intensity dry-land workouts suggested that my state of nutritional ketosis did not completely impair my ability to store or export hepatic glucose. This is a very important point! Why? Because, it runs counter to the “conventional wisdom” of low-carb (or ketotic) nutrition with respect to physical performance. We are “told” that without carbohydrates we can’t synthesize glycogen (i.e., we can’t store glucose). However, those who promote this idea fail to realize that glycerol (the backbone of triglycerides) is turned into glycogen, along with amino acids, not to mention the 20 to 40 gm of carbohydrates I consume each day (since my brain doesn’t need them). We know muscles still store glycogen in ketosis, as this has been well studied and documented via muscle biopsies by Phinney, Volek, and others. But, my little self-experiment actually adds a layer to this. Because muscle can’t export glucose (muscle lacks the enzyme glucose-1-phosphatase), we know that the increase in my blood glucose was accounted for by HGO – my liver exporting its glycogen. In other words, ketosis does not appear to completely impair hepatic glycogen formation or export. Again, we’d need controls to try to assess how much, if any, hepatic glycogen formation and/or export is inhibited. It’s hard to make the argument that being in ketosis is allowing me to swim and do high intensity training with greater aptitude, and as I’ve commented in the past, I feel I’m about 5-10% “off” where I was prior to ketosis for these specific activities, but at the same time, I could be doing more to optimize around them (e.g., spend less time on my bike which invariably detracts from them, supplement with creatine which may support shorter, more explosive movements), which I am not.

Lesson 3

Consuming “massive” amounts of super starch (50 gm on the ride), did not seem to adversely affect my ketotic state. My total carbohydrate intake for that day, including what I consumed for the other 18 hours of the day, was probably close to 90 gm (50 gm of super starch plus 40 gm of carbs from the other food I ate). This suggests one or two possibilities:

- Because of the molecular structure of super starch (I’ll be discussing this in the future, so please hold questions) and the concomitant metabolic profile that follows from this structure, it may not inhibit ketosis like other carbohydrate, and/or

- During periods of profound physical stress insulin secretion is being sufficiently inhibited that higher-than-normal amounts of carbohydrate can be tolerated without negatively impacting ketone production.

This is pretty straightforward to test, even in myself. I just haven’t done so yet.

Lesson 4

While it’s probably the case that my liver has less glycogen (i.e., stored glucose) at any point in time, relative to what would be present if I were eating a high-carb diet, it’s not clear this matters, at least for some types of workouts. Why? Take the following example:

- Someone my size can probably store about 100 gm of hepatic (liver) glycogen and about 300 gm of muscle glycogen at “full” capacity. This represents about 1600 calories worth of glucose – the most I can store at any one time.

- Before I was ketotic, my RQ at 60% max VO2 (about 2,500 mL of O2 per min consumption) was nearly 1.00, so at that level of power output (a pace I can hold for hours from a cardiovascular fitness standpoint) I required 95% of my energy to come from glycogen. So, how long do my glycogen stores last? 2,500 mL of O2 per minute translates to about 750 calories per hour, so I would be good for about 2 hours and 15 minutes on my glycogen stores.

- Contrast this with my ketotic state. Let’s assume my glycogen stores are now only half what they were before. Muscle biopsy data suggests this is probably an overly conservative estimate, but let us assume this to be the case. Now I only store 50 mg of hepatic glycogen and 150 gm of muscle glycogen, about 800 calories worth of glucose.

- In ketosis, my RQ at 60% max VO2 is 0.77 (at last check), telling me I am getting only 22% of my energy from glucose and the remaining 78% from fat. So, how long do my depleted glycogen stores last? Nearly 5 hours. Why? Because I barely access glucose at the SAME level of oxygen consumption and the same power output.

I know what you’re thinking…why is this an advantage? Just consume more glucose as you ride! It’s not that simple, but you’ll have to wait until my upcoming post, “What does exercise have to do with being in the ICU” to find out.

Going back to the black sheep example I open Part I of this post with, we know that at least one person in nutritional ketosis seems to make enough liver and muscle glycogen to support even the most demanding of his energetic needs.