Regular physical activity is one of the most important things people can do to improve their health according to the national physical activity guidelines. Exercise is associated with the reduction in risk of many adverse conditions, including the four horsemen of chronic disease: metabolic dysregulation, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and neurodegeneration. (Metabolic dysregulation has many faces, including type 2 diabetes, systemic insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.) Exercise is also associated with a lower risk of chronic lung disease, as well as with a lower risk of frailty and the debilitating or deadly falls and injuries that accompany it. In other words, exercise is associated with a lower risk of the conditions that kill the majority of US adults over the age of 40. Exercise might be the most potent “drug” we have for extending the quality and perhaps quantity of our years of life.

But the benefits of exercise on mortality have never been assessed in the setting of a randomized controlled trial (RCT), which can help us determine if there’s a cause-and-effect relationship. Is exercise a marker or a maker of improved health? Are all types of exercise created equal when it comes to longevity? Until recently, these questions had not been addressed in an RCT. Enter the Generation 100 study, the results of which were published in October of 2020 in the BMJ: “Effect of exercise training for five years on all cause mortality in older adults—the Generation 100 study: randomised controlled trial.”

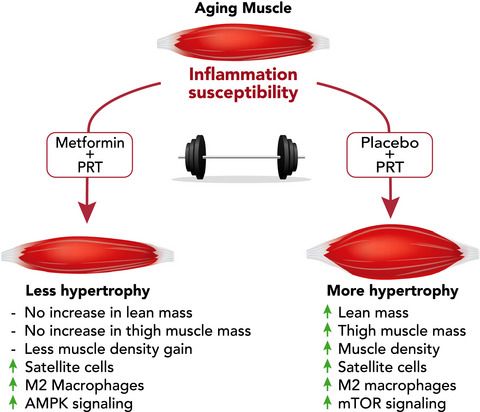

Want more content like this? Check out our episode on the importance of muscle mass, strength, and cardiorespiratory fitness for longevity and our article on metformin and exercise.

About the Generation 100 Study

Researchers from Norway conducted a five-year study to test the effect of exercise and mortality in adults in their seventies living in the city of Trondheim. More than 1,500 participants in this study were randomized into one of three groups: a control group, high-intensity interval training (HIIT), or moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT).

About half of the participants were assigned to the control group and were asked to follow the Norwegian physical activity guidelines for 2012, which recommends 30 minutes of moderate-level physical activity almost every day. The recommendations tell adults—including the elderly—to engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity throughout the week, or engage in at least 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity throughout the week, or engage in an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity.

The other half of participants were assigned to the HIIT or MICT groups. Participants in the HIIT group were asked to exchange two of the five 30-minute moderate-intensity physical activity sessions each week (as recommended by Norwegian health authorities) with two “4-by-4” HIIT sessions, consisting of a 10-minute warm-up followed by four four-minute intervals at approximately 90% peak heart rate with three minutes of active recovery (about 60% of peak heart rate) in between. Participants in the MICT group were asked to exchange two of the five guideline-recommended 30-minute moderate-intensity physical activity sessions each week with two MICT sessions, consisting of 50 minutes of continuous work at about 70% of peak heart rate.

All participants were asked to follow their respective protocols for five years. Every sixth week, both the HIIT and MICT groups met separately for supervised spinning sessions with an exercise physiologist, wearing heart rate monitors to ensure the recommended heart rates were achieved. Supervised training with exercise physiologists present was also offered twice per week in different outdoor areas over the course of the study. For the control group, no supervision was provided.

After five years, just under 5% of the participants assigned to the control group had died, while the mortality rates in participants assigned to the HIIT and MICT groups were about 3% and 6%, respectively. The combined mortality rate of the HIIT and MICT participants was 4.5%.

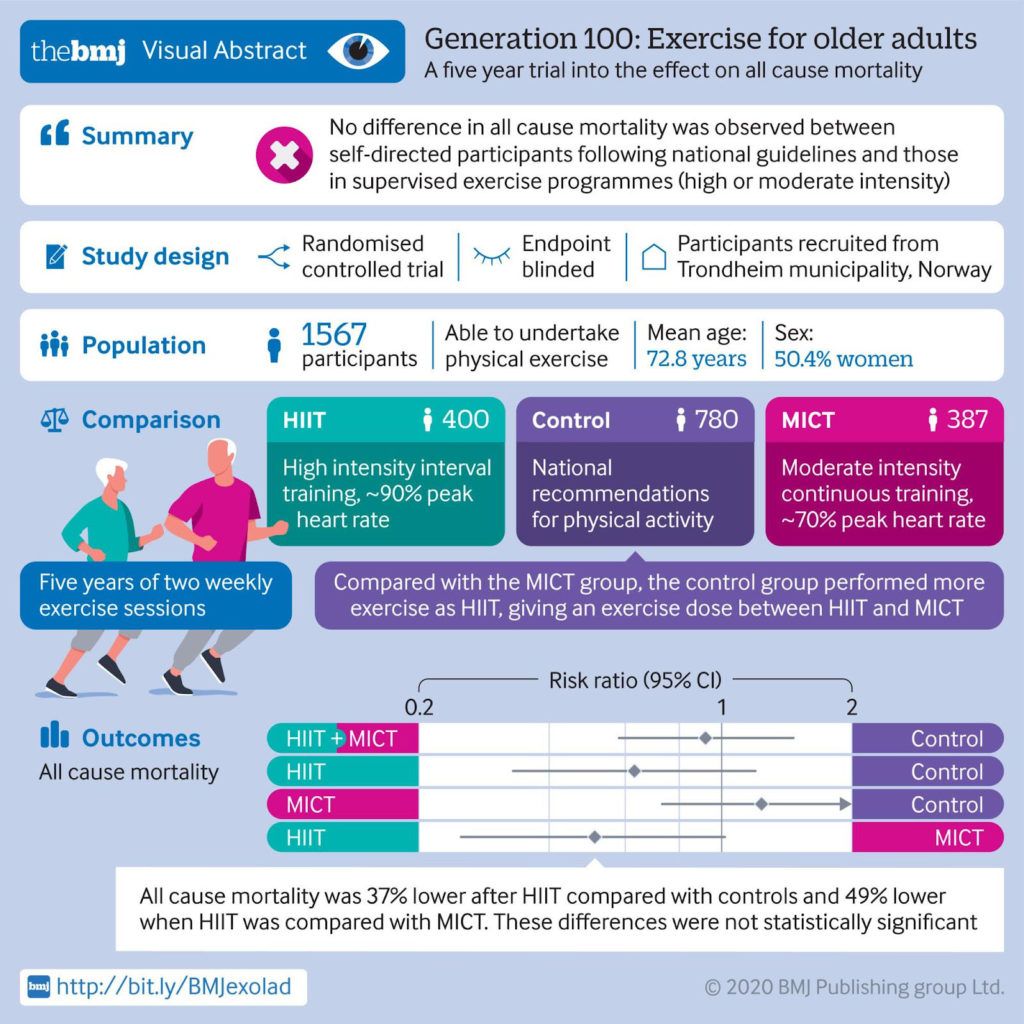

The investigators concluded that combined MICT and HIIT has no effect on all-cause mortality compared with recommended physical activity levels, but they did observe a lower all-cause mortality trend in the participants assigned to HIIT compared with those assigned to MICT and controls. All-cause mortality was nearly 40% lower in participants assigned to HIIT compared with controls, and about 50% lower when HIIT was compared with MICT, but these differences were not statistically significant. The New York Times reported on the trial with the following headline: “The Secret to Longevity? 4-Minute Bursts of Intense Exercise May Help.” A visual abstract of the study is provided in the Figure below, courtesy of the BMJ.

Figure. Visual abstract of the Generation 100 study.

Understanding the Results of the Generations 100 Study

Given the results, should we conclude that exercise has no effect on all-cause mortality? Recall that participants in the control group were asked to follow the Norwegian physical activity guidelines, which recommends 30 minutes of moderate-level physical activity almost every day. Again, the Norwegian guidelines, which are almost a carbon copy of the US guidelines, recommend that all adults — including the elderly — engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity throughout the week, or engage in at least 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity throughout the week, or engage in an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity. The recommendations also add that the amount of daily activity needed to avoid weight gain is about 60 minutes of moderate-intensity activity or a somewhat shorter duration of vigorous-intensity activity.

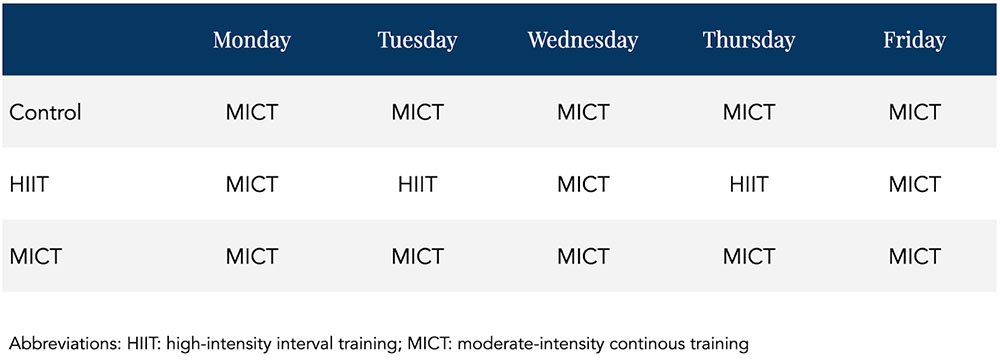

Also recall that the control group was compared to a HIIT and MICT group, which were essentially asked to follow the same recommendations as the control group three days out of the week. HIIT and MICT groups only differed from controls in that they were asked to exchange two of the 30-minute moderate-intensity physical activity sessions each week with two days of HIIT and MICT sessions, respectively. The control group was essentially asked to do five half-hour MICT sessions per week. The MICT group was asked to do five MICT sessions per week with three sessions lasting 30 minutes and two sessions lasting 20 minutes longer. The HIIT group was asked to do three 30-minute MICT sessions per week and two HIIT sessions per week.

How different is the control group from the MICT group? Not much. In fact, looking at the Table below showing possible weekly schedules for each group, the control and MICT groups would seem completely identical.

Table. Theoretical weekly exercise schedule for the three arms of the study.

Limitations of Randomized Control Trials (RCTs)

Essentially, the study compared people asked to exercise regularly with people asked to exercise regularly with occasional supervision. Here was an opportunity to “find out if exercise directly affects lifespans,” as the Times put it, and yet the investigators designed a control group that wasn’t suitable to find this out. With virtually no difference in the variable of interest between control and experimental groups, statistically significant differences in results would be highly unlikely even if a true association were present.

Why didn’t the investigators ask participants in the control group to be sedentary in order to test the effect of exercise on mortality? According to the Times, the investigators felt that it would be unethical. Do you see the dilemma? In order to conduct a proper RCT to find out if exercise has an effect on mortality, researchers need a control group that is asked not to exercise. If they think that’s unethical, it means they’re already convinced that exercise directly affects lifespans.

The investigators acknowledged the high level of physical activity in the control group, “which probably reduced the study’s ability to detect statistically significant effects of exercise training on primary outcomes.” They suggested that “New concepts or study designs are needed to avoid the Hawthorne effect in future studies.” The Hawthorne effect refers to the alteration of behavior by the participants of a study due to their awareness of being observed. Without getting into obvious reasons why there was such a high level of adherence in this study independent of the Hawthorne effect, this brings up another dilemma. The researchers suggest the use of new study designs for further investigation, presumably designs in which the control group is less active than they were in this published study. But if these investigators, who believe that asking people to be sedentary is unethical, came up with a new concept or study design intended to make the control group more sedentary than the intervention groups, wouldn’t they still encounter the same ethical concerns? It’s difficult to reconcile the fact that one of the supposed problems with this study is that the control group followed their assignment too well.

The bottom line is that the control group is completely inappropriate from the standpoint of trying to determine cause and effect in this study. Instead, the best the investigators could do based on their design is to test whether asking people to exercise with occasional supervision lowers mortality compared with asking people to exercise with no supervision. I think that’s a shame. But the goal of establishing rigorous scientific evidence for well-known health principles does not justify willfully causing harm (or withholding help) to a group of people. No RCT is necessary to prove, for instance, that having crude arsenic for breakfast increases mortality relative to eating eggs and toast, and to run such a study would constitute mass murder, not science.

The looming question is: where do we draw the line? Are we already so confident that exercise directly affects lifespans that this question should be similarly exempt from a randomized controlled clinical trial? And how do we gain further reliable insight into such “forbidden” research questions? Most likely, a combination of approaches is needed. We might find some utility in certain observational data, as well as in cellular mechanistic studies. Further, randomized study designs can often be applied to address topics highly relevant to the research question – for instance, one might test effects of shorter-term exercise patterns on molecular markers associated with chronic disease risk.

On the question of exercise and longevity, various alternative investigation approaches each might provide only a small piece of the puzzle. But together, they’d likely stand a better chance of answering this question than a single study designed with an inadequate control group and practically no chance of detecting a true underlying effect.

– Peter