Check out more content about skipping breakfast:

-

- (May 12, 2019) The Bad Science Behind ‘Skipping Breakfast’

- (October 24, 2021) Does skipping breakfast increase the risk of an early death? Part I

- (October 31, 2021) Does skipping breakfast increase the risk of an early death? Part II

Over the past few years, I’ve received an increasing number of papers suggesting that skipping breakfast poses a danger to health, whether by increasing risk of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, or even all-cause mortality. Recently, a group of investigators from Texas Tech University (TTU) claimed their study published in Cancer Causes & Control provides evidence for the benefits of regular breakfast consumption in reducing the risk of all-cause and cancer mortality. (The contrapositive: skipping breakfast increases the risk of all-cause and cancer mortality.) But does it, really? In this post, I review this study (referred to as the “TTU study” henceforth) to shed some light on why their conclusions are misguided. My hope is that this may serve as a template for critical examination of all other observational epidemiology studies on the topic of skipping breakfast, including those still to come.

There are three inevitabilities in life: death, taxes, and bad observational nutritional epidemiology. To generate reliable knowledge in public health, the necessary prerequisite is performing rigorous, well-controlled, and often long-term, randomized experiments. Doing so is often difficult and expensive, but observational epidemiology is hardly an acceptable compromise.

This is a two-part email series. Part I focuses on the TTU study and whether we should accept its conclusions, while Part II will cover the broader body of literature on skipping breakfast and its association with health. Let’s get started with examining the TTU study using a series of questions you should always be asking when studying studies.

Where did the data come from?

The authors relied on data collected as part of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES III): a nationwide study conducted between 1988 and 1994 on the health and nutrition of nearly 40,000 adults and children. Participants answered a questionnaire administered by an interviewer, underwent a physical, and provided specimens like blood, saliva, and urine. The TTU investigators analyzed data from 7,007 of these participants, limiting their analysis to those aged 40+ years at the time of the study. By checking death certificate records through 2015, the researchers also collected follow-up data on deaths within this cohort, as well as deaths from cancer specifically.

During the baseline NHANES III interviews, participants were asked how often they ate breakfast, falling into one of three categories: (1) those who eat breakfast every day; (2) those who eat breakfast some days; and (3) those who rarely or never consumed breakfast. What defined “breakfast,” exactly? After all, all of us “break the fast” and eat our first meal of the day at some point. In the survey, the definition is left up to the respondent. “For some people, breakfast may only mean a cup of coffee,” the interviewer’s manual explains, “for others it may mean eggs benedict at 10:00 a.m.” Subjective, to say the least. For the sake of simplicity, I’ll refer to two groups for the most part from here on out: the breakfast eaters (i.e., those who eat breakfast every day) and the breakfast skippers (i.e., those in groups 2 and 3 above that don’t consume breakfast every day). Just make sure you keep these two things in mind along the way: (1) this is self-reported information from a single baseline questionnaire (when I refer to participants as “breakfast eaters” or “breakfast skippers,” remember that it’s more accurate for me to say that the participants self-reported these habits.); and (2) all 7,007 participants are assumed to have continued this same pattern of consumption every day for the next couple of decades through follow up.

How did the investigators analyze the data?

Randomized experiments assure that each group has the same demographics, and perhaps most importantly, randomization minimizes measured — and unmeasured — confounding factors. For example, take 20 inbred mice at 6 months of age, randomize half to a diet with rapamycin mixed into their chow while the other half receive a placebo. Other than the drug, all conditions are the same. If you compare the baseline characteristics of the two groups of mice, they are identical. Randomized experiments in humans try to reflect this level of rigor.

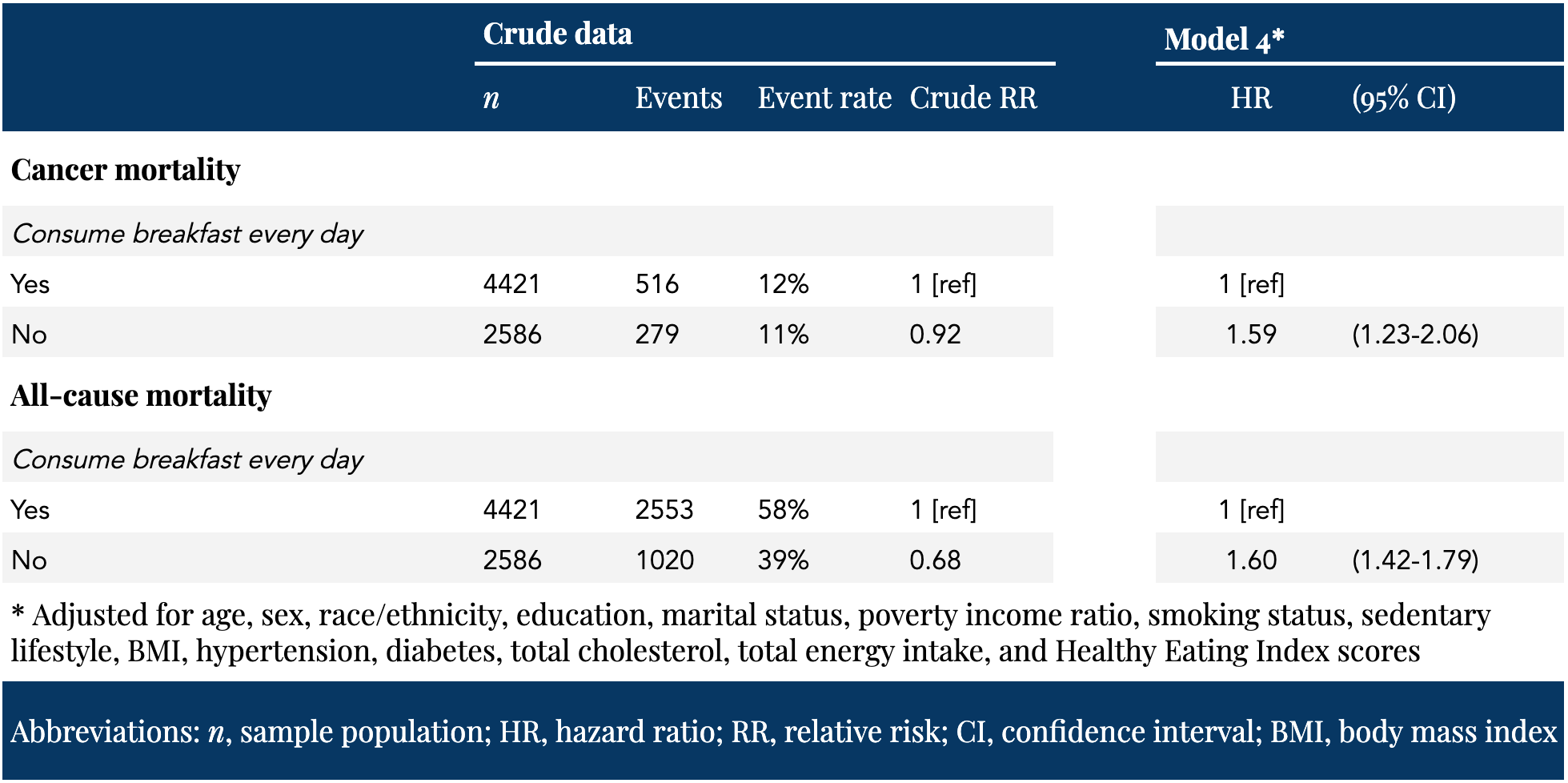

In contrast, the TTU study was not randomized, and investigators needed to rely instead on statistics to adjust for all of the differences between groups and isolate their (independent) variable of interest: skipping breakfast. (For a brush-up on randomization and confounding, please refer to Part IV of our Studying Studies series, which covers these topics in detail.) Using statistical models adjusting for age, sex, race and ethnicity, education, marital status, income, smoking, physical activity, body mass index (BMI), hypertension, diabetes, cholesterol levels, total energy intake, and diet quality, individuals who did not consume breakfast every day had an associated 59% higher risk, or a 1.59 hazard ratio (HR), of cancer-related mortality, and a 60% higher risk, or a 1.60 HR, of all-cause mortality compared to those who ate breakfast every day. Before running for a box of Lucky Charms, we have a few questions based on this information. Let’s take them one at a time.

What were the baseline characteristics of the participants and were there any notable differences between the breakfast skippers and breakfast eaters?

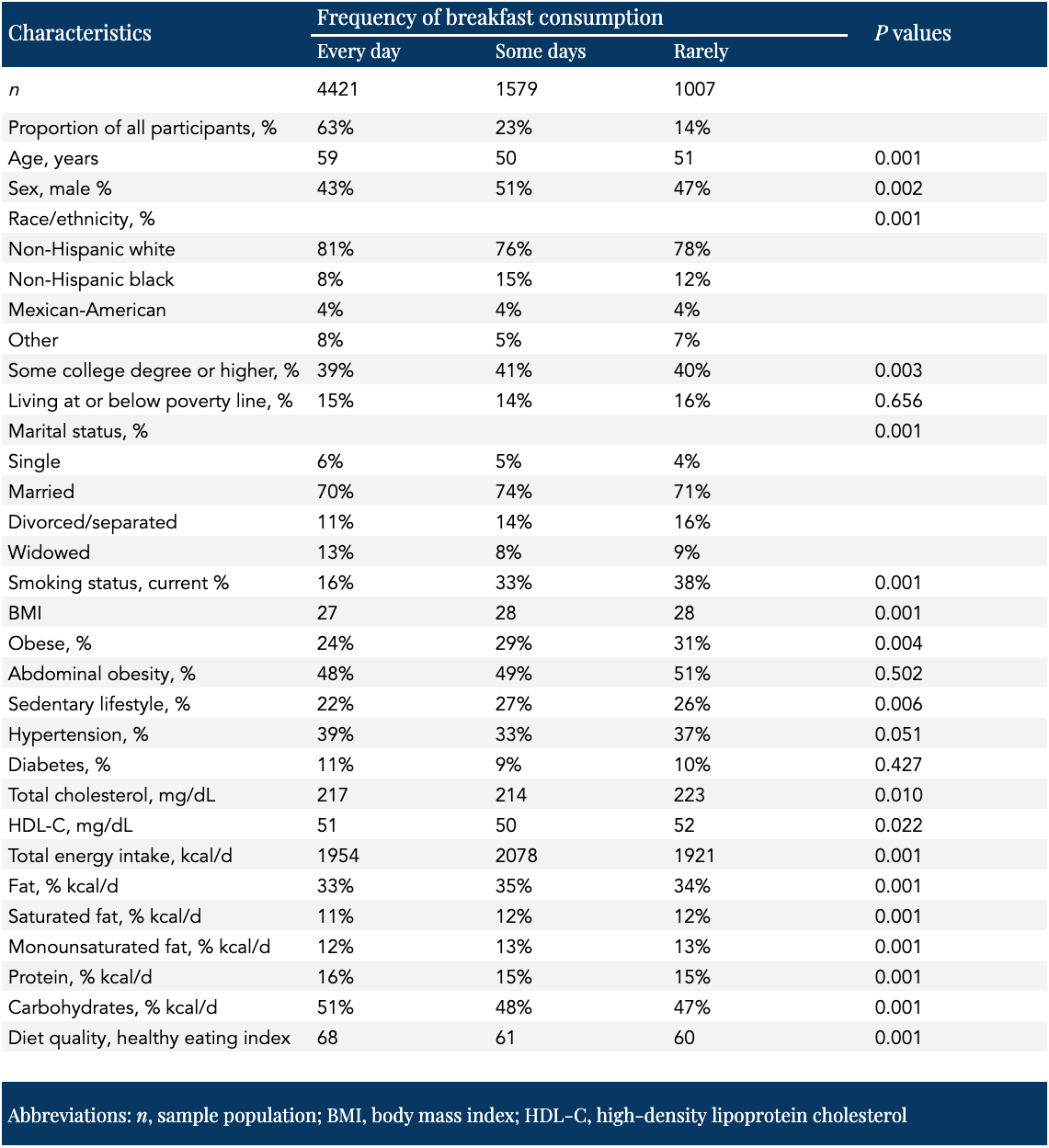

As shown in Table 1 below, compared to participants who consumed breakfast every day, those who didn’t were significantly younger, current smokers, obese, physically inactive, divorced or separated, had higher cholesterol levels, had a lower percentage of their calories from proteins and carbohydrates and a higher percentage from fat and saturated fat, ate fewer overall calories per day, and had lower diet quality scores. (Regular consumers of human clinical trial literature will note that in randomized clinical trials, baseline characteristics, by definition, demonstrate no significant differences between groups.)

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants according to frequency of breakfast consumption, NHANES III 1988–1994 — adapted from Helo et al., 2021

The TTU study is a prime example of what is referred to as the healthy-user bias. (For more on the healthy-user bias, check out Part III of the Studying Studies series.) People who are health-conscious are different from people who are not in myriad ways, some of which we can’t identify and therefore can’t adjust for statistically.

“Breakfast is often considered as the most important meal of the day,” the investigators write, “due to its potential to contribute to better nutrient adequacy.” We’ve heard this for decades. (I wrote about [the absurdity of] this topic last year.) We’ve also been told not to smoke (or if we do smoke, quit), to avoid becoming overweight, to exercise, and to lower our cholesterol levels if they become elevated. We’ve been told to consume more fruits and vegetables, fish, whole grains, and unsaturated fats, and to consume less sodium, saturated fats, and added sugar. (All of these dietary components are baked into the diet quality score used in the TTU study, shown in the bottom row of Table 1.)

Looking at Table 1, we see striking health and lifestyle differences between the two groups. The problem here is clear: breakfast skippers are less health-conscious overall than breakfast eaters. Take smoking, for example, possibly the most significant known modifiable risk factors for all-cause and cancer mortality. Individuals who skipped breakfast the most often were almost three times as likely to be smokers than those who consumed breakfast regularly. All of these differences in health and lifestyle characteristics between groups can either mask or exaggerate the association between frequency of breakfast consumption and mortality. As mentioned above, the researchers controlled for these differences using statistical adjustments, but adjusting for every habit, characteristic, and lifestyle simply isn’t possible.

The only “risk factor” known to be more important than smoking for all-cause and cancer mortality is age, which of course is not modifiable (unfortunately). Looking at the top of Table 1, we see that breakfast eaters are, on average, almost a full decade older than breakfast skippers. So on one hand, breakfast eaters are clearly more health-conscious than breakfast skippers. On the other, those breakfast eaters are nearly 10 years older than their counterparts in a study where age is the most important risk factor for the two outcomes of interest. Which group had higher rates of all-cause and cancer mortality before taking into account any statistical adjustments made by the investigators? Let’s take a look at Table 2 to find out.

Table 2. Association between the frequency of breakfast consumption and all-cause and cancer-related mortality, NHANES III 1988–2015 — adapted from Helo et al., 2021

On the left side of Table 2 is the crude, or unadjusted, event data provided by the corresponding author (personal communication, email). Note how different the event rates are before the investigators applied their statistical correction models. Without any statistical adjustment, skipping breakfast is associated with a 32% reduction in all-cause mortality and an 8% reduction in cancer mortality compared to regularly consuming breakfast.

This crude difference in mortality may simply be explained by age. Remember, this is a two decade follow-up on two groups with a significant discrepancy in average age: if the average breakfast skipper and average breakfast eater survived until the TTU follow-up, they would be 72 and 81 years old, respectively. After the investigators adjusted for several factors, the associated risk swung in the other direction: skipping breakfast was then associated with a 60% and 59% increase in all-cause and cancer mortality, respectively.

This swing is heavily driven by age. When the investigators adjusted for age alone, the associated risk was very similar to the risk calculated by adjustment for age and 13 additional factors. The age-only adjusted model yielded an HR of 1.55 and 1.61 for all-cause and cancer mortality, respectively. After adjusting for age and 13 additional factors, HRs were 1.60 and 1.59, respectively.

Are we sure the investigators adjusted for all of the potential confounding factors and are we sure the adjustment completely isolates the variable of interest?

Not only is it impossible to adjust fully all characteristics that might affect the outcomes of interest, there are myriad other knowable and unknowable factors which, though unaccounted for, might explain observed associations. This is referred to as residual confounding. (This definition also includes measurement errors in factors that were included in statistical adjustments.) For example, perhaps the quality and duration of sleep differs on average between breakfast eaters and breakfast skippers. Maybe some participants reported skipping breakfast because they were shift workers and considered their first meal of the day to be lunch. The possibilities are virtually endless. Many other factors may be at play, and the unfortunate reality is that we just don’t know what we’re not looking for. This is why randomization is so important: by randomizing participants before an intervention, you minimize the impact of measured and unmeasured confounding factors.

Does regular breakfast consumption reduce the risk of all-cause and cancer mortality?

Looking only at baseline characteristics, we can already determine that the TTU study fails to provide reliable knowledge. Skipping breakfast is just one of many characteristics that differ between groups, stymieing any attempt to determine whether skipping breakfast in this population is a marker or a maker of chronic disease. The investigators themselves concede this point. “Taken together,” the investigators write, “the seemingly reduced all-cause and cancer mortality risk among persons who consume breakfast every day may simply be the reflection of habitual breakfast consumption being a proxy for a health-conscious lifestyle [emphasis added].”

Does regular breakfast consumption reduce the risk of all-cause and cancer mortality? The TTU study is not designed to answer this question. Semantically, no person in history managed to avoid death, so the more relevant question is whether regular breakfast consumption will extend lifespan compared to skipping breakfast. Regarding cancer, if skipping breakfast is truly associated with increased cancer mortality relative to regular breakfast consumption, it’s important to know the mechanism underlying that relationship. For that, we’ll need to look at the broader body of literature on skipping breakfast and its association with health and harm. But that we’ll save for Part II.

§

As I mentioned above, we’re in the process of hiring a physician for our practice. Your enthusiasm, interest, and network continue to be one of the most valuable recruiting tools our team leans on when searching for new talent. While our practice is small, I am looking to add another physician to support our patients. Our preferred candidate is ideally an internist, with strong clinical knowledge in lipidology, metabolic health, exercise, nutrition, and endocrinology, in addition to a demonstrated interest in the science of increasing human lifespan and healthspan. The full job description and application process can be viewed on our Careers page.

Thank you for your interest in joining my team or sharing this role with someone in your network who you think might be a strong fit.

Please do not respond directly to this email, as the volume of email that comes through this address is high, and such responses can be missed. To ensure we receive your application, please submit and apply for the job through our Careers Page, only.

– Peter