If I held a crystal ball 10 years ago, I’m not sure I would’ve believed it if it showed me the increased interest in the ketogenic diet would look like the figure below. That’s 2 logs, folks.

Admittedly, I started my journey on this path in 2009, with a deep dive into ketosis in the Spring of 2011, but it seemed so obscure! (For a timeline of what I did, I think I covered it somewhere in this talk…yes I’m too lazy to actually confirm this by skimming through it.) All told I spent approximately 3 years in the strictest state of nutritional ketosis (NK) with one very memorable deviation when I had 6 or 7 full-sized and upsettingly decadent desserts circa September 2013. I believe the diet helped me transition from metabolic syndrome to metabolic health and I certainly thought it could benefit other people. This nutritional state could gain some steam, I thought.

I was well aware of the dearth of mainstream knowledge of NK, and particularly the conflation of NK with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a pathologic state that results from the complete or near absence of insulin, which is what prompted my writing and desire to share my journey. And I was once in the wanker category of folks who spoke with “authority” about ketosis, despite knowing somewhere between zero and nothing on the topic. I remember exactly where I was sitting in a clinic at Johns Hopkins in 2002 during my residency explaining to (admonishing, really) a patient who was on the Atkins diet how harmful it was because of DKA. Not only that, the ketogenic diet could be seen as the antithesis of a “healthy” diet by conventional standards. I could see how this was a difficult proposition for many to acknowledge.

The beautiful part of good science is its self-correcting nature. The ugly part is this self-correcting nature often moves at a glacial pace—and it’s not linear. We often view history century-by-century and see what amounts to continual progress in medicine. But we live our lives—and consume information—day-by-day, exposed to the peaks and valleys of medical wisdom.

Looking back on my earlier posts on ketosis—and explaining what I eat, for example—makes me both chuckle and cringe. I remember how bizarre the diet seemed to many readers and the general public at the time. I also remember digging into the literature and learning, for example, that my alma mater, Johns Hopkins had been using the ketogenic diet to treat pediatric epilepsy for almost a century…and being so embarrassed about admonishing that patient I saw in my residency.

Since then, it’s safe to say I dove down the rabbit hole. The more I learned, the more I grew tired of reading so much misinformation on the topic. While there are more thoughtful people and articles on the subject of ketosis these days (e.g., here’s a thoughtful video on ketosis and ketogenic diets from one of my most important ketosis mentors, Steve Phinney, a co-founder of Virta Health1Disclosure: I’m an investor in, and advisor to, Virta Health.), there are still pieces like the one Vox published this month, that doesn’t exactly do the topic justice.

Like many variables in diet, health, and disease, it behooves us to look beyond the bumper sticker explanation. I want to highlight a couple of posts I wrote, to attempt to provide a little more nuance and understanding to the subject: “Ketosis — advantaged or misunderstood state?” Parts I and II. Part I follows below. I’m hoping to write more on the topic in the not-too-distant future since there’s been a number of intriguing papers published recently (certainly since 2012). But I also wanted to bring these back into focus in light of the information I’m seeing more of on the interwebz. (You can also visit the Ketosis section of the site to view more articles on the subject.)

Because I know people will ask, I have not been on a ketogenic diet “regularly” since about mid- to late-2014. The reasons are too nuanced to describe here, but my deviation is not because I lost confidence in its efficacy. With nearly a decade of clinical experience, I can safely say I was an outlier (in the best sense) with respect to my physiology and response. I was leaner, and more mentally and physically fit during this three year period than during any other period of time as an adult, and my biomarkers were as good as they had ever been. I’ve also seen the benefit of ketogenic diets first-hand on my patients and my own sister, a remarkable story I hope to share one day. But I’ve also been humbled by my inability to explain why some people have suboptimal or even negative responses to NK. I would say, all things considered, my knowledge of ketosis is greater today than when I was writing about it voraciously, but my confidence in my understanding of it, might actually be lower. As the saying goes, the further one goes from shore, the deeper the water gets.

—P.A., April 2018

§

(Part I: originally posted November 26, 2012)

In part I of this post I will see to it (assuming you read it) that you’ll know more about ketosis than just about anyone, including your doctor or the majority of “experts” out there writing about this topic.

Before we begin, a disclaimer in order: If you want to actually understand this topic, you must invest the time and mental energy to do so. You really have to get into the details. Obviously, I love the details and probably read 5 or 6 scientific papers every week on this topic (and others). I don’t expect the casual reader to want to do this, and I view it as my role to synthesize this information and present it to you. But this is not a bumper-sticker issue. I know it’s trendy to make blanket statements – ketosis is “unnatural,” for example, or ketosis is “superior” – but such statements mean nothing if you don’t understand the biochemistry and evolution of our species. So, let’s agree to let the unsubstantiated statements and bumper stickers reside in the world of political debates and opinion-based discussions. For this reason, I’ve deliberately broken this post down and only included this content (i.e., background) for Part I.

What is ketosis?

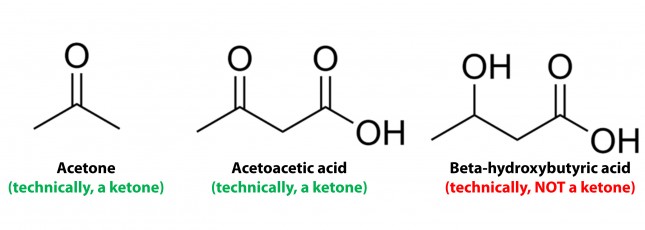

Ketosis is a metabolic state in which the liver produces small organic molecules called ketone bodies at “sufficient” levels, which I’ll expand upon later. First, let’s get the semantics correct. The first confusing thing about ketosis is that ketone bodies are not all – technically — ketones, whose structure is shown below. Technically, the term ketone denotes an organic molecule where a carbon atom, sandwiched between 2 other carbon atoms (denoted by R and R’), is double-bonded to an oxygen atom.

Conversely, the term “ketone bodies” refers to 3 very specific molecules: acetone, acetoacetone (or acetoacetic acid), and beta-hydroxybutyrate (or beta-hydroxybutyric acid), shown below, of which only 2 are technically ketones. (The reason beta-hydroxybutyrate, or B-OHB, is not technically a ketone is that the carbon double-bonded to the oxygen is bonded to an –OH group on one side, technically making B-OHB a carboxylic acid for anyone keeping score.)

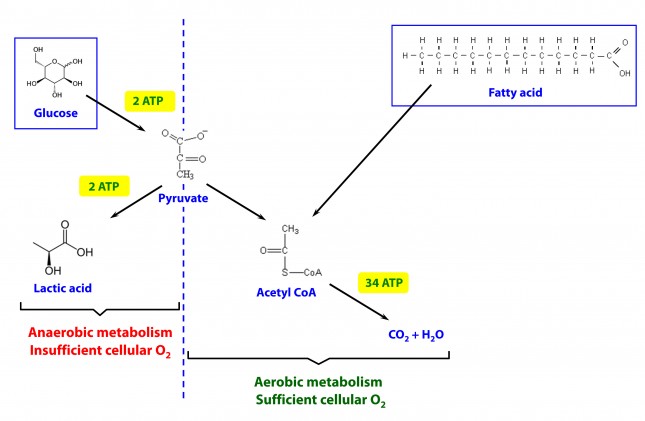

Now, back to the real question at hand. Why would our body make these substances? To understand why or when the body would do this requires some understanding of how the body converts stored energy (the food we eat or the energy we store in our body, i.e., fat or glycogen) into phosphate donors. For a refresher on this process, please refer to the video in this post, specifically the section from 2:15 to 13:30.

The ATP issue

As you may recall, about 60% of the energy we expend, say 1,800 kcal/day for someone consuming 3,000 kcal/day in weight balance, is purely devoted to keeping us alive by generating enough ATP (“energy currency”) to do 2 things: allow ion gradients to function and allow muscular relaxation. So, obviously, we can’t tolerate – literally even for one minute – insufficient ATP production. In fact, one of the most potent toxins known to man (cyanide) exerts its effect on this process by inhibiting the electron transport chain which generates the bulk of the ATP our body produces. Even the most transient interruption of this process is fatal.

Take home message #1: No ATP, even for 1 minute, equals no life.

The brain issue

The brain is a particularly greedy organ when it comes to energy requirement. To put this comment in perspective consider the following: though our brain represents only about 2% of our body mass, it accounts for about 20% of our energy expenditure. (In children, by the way, this may be closer to 40-50% of basal metabolic demand.) So, beyond the ATP issue, above, there is a substrate issue with the brain as neurons derive most of their energy from glucose. While there is emerging evidence that neurons can also oxidize fatty acids directly in small amounts and may even prefer lactate (over glucose), these two substrates do not approach the levels of consumption by neurons that glucose does. So, for the purpose of this discussion, let’s just focus on the need of the body to provide glucose to the brain.

You’ll recall, from the point I made above, that my brain requires about 400 to 500 kcal of glucose per day (100 to 120 gm). You’ll also recall (from the video, above) that I can store about 100 to 120 gm of glucose in my liver. While I can store much more in my muscles, (on the order of about 300 to 350 gm), because muscles lack the enzyme glucose-6-phosphatase, glucose stored in muscle as glycogen is unable to re-enter the bloodstream and is meant for the muscle and the muscle alone to use. In other words, muscle glycogen is a stranded asset of glucose in the body to be used only by the muscle.

So, if I’m deprived of a dietary source of glucose, I depend solely on my liver to release glycogen (a process known as hepatic glucose output, or HGO). How long can HGO supply my brain with sufficient glucose? It depends on a few things that impact both the “source” and the “sink” of glucose. Other competing sinks for glucose (e.g., activity level, thermogenic needs) and sources (e.g., glycerol and gluconeogenic amino acid availability) can make a difference for a while. But, in a state of starvation we’ve only got about one to three days before we’re in trouble. If our brain doesn’t get a hold of something else, besides glucose, we will die quite unceremoniously.

Take home message #2: No glucose for 24-72 hours equals the need for something else the brain can use instead (that is not fat or protein, since neurons can’t oxidize fat and the last thing we want to do is start muscle wasting at a geometric rate).

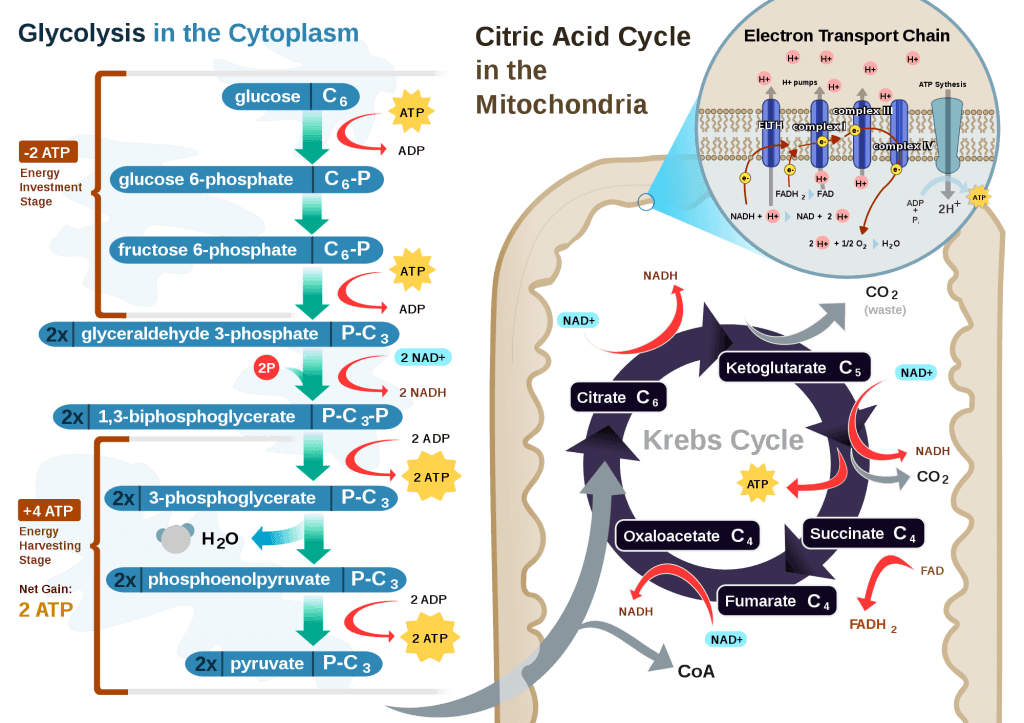

The Krebs Cycle

This poses a real evolutionary dilemma. We need an enormous amount of energy just to not die, but the single most important organ in our body (also quite energy hungry in its own right) can’t access the most abundant source of energy in our body (i.e., fat) and is, instead, almost solely dependent on the one macronutrient we can’t store beyond a trivial amount (i.e., glucose). Obviously our species wouldn’t be here today if this were the end of the story. But, to understand how we survived requires one more trip down biochemistry memory lane. In the figure below (also included and described in the video) I gloss over a pretty important detail.

How, exactly, does our body take pyruvate (from glucose) or acetyl CoA (from fat) and generate so much ATP? The answer lies in the beauty of the Krebs Cycle, which feeds into a process called the electron transport chain (or ETC), I alluded to above. Since the adage ‘you can’t get something for nothing’ is as true in biochemistry as it appears to be in life, to get all that ATP (i.e., stored energy in the form of the phosphate bond), we need to give up something. What the ETC does give up, as its name suggests, is electrons. Through a series of redox reactions the ETC trades the stored energy held by electrons going from higher to lower energy states in exchange for the chemical energy stored in the bonds of the third phosphate group on an ATP molecule.

To think of it another way, if you start with stored energy – glucose or fat, for example, which if burned in calorimeter will give off varying amounts of heat – and you’re willing to convert their carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen molecules into another form with less energy – water and carbon dioxide which, if burned, produce very little heat – it’s a fair trade! The ETC is simply the vehicle that allows our body to make the switch.

In a car, by contrast, it’s much simpler. The engine combusts the hydrocarbon (e.g., gasoline) directly and in one flash liberates the heat contained within the hydrogen-carbon and carbon-carbon bonds in exchange for carbon dioxide, water vapor, and a few other things.

If you take a look at the figure, below, you’ll get a sense of the moving pieces involved in this cyclic transfer process. Molecules shuffle back and forth, around the cycle, and kick off spent carbon (carbon dioxide, termed “waste”) and reducing agents (e.g., conversion from NAD+ to NADH) for the ETC.

Where do the ketones come in?

In the absence of acetyl CoA (several ways this can happen, including substrate shortage, as I’m describing here) we evolved a cool trick. Our liver can make – out of fat or protein, though we much prefer to use fat so we can spare our protein and prevent severe muscle wasting – something called beta-hydroxybutyrate, one of the 3 ketone bodies I described above.

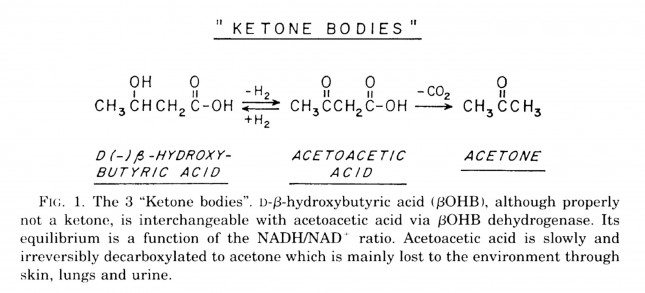

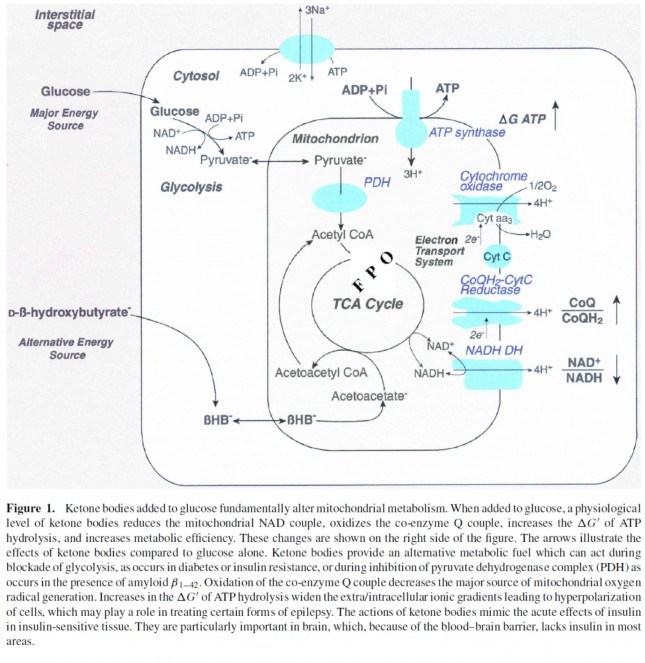

B-OHB and acetoacetate (see figure below from this paper by Cahill and Veech, 2003) are produced by the liver from long and medium chain fatty acids and released into the bloodstream.

Acetoacetic acid and B-OHB live in reversible equilibrium (on the left), but once acetoacetate is converted to acetone (on the right) there’s no going back.

Now take a look at the figure below, from this 2001 paper. This is another rendition of the figure above showing the Krebs Cycle, but here you can see where B-OHB and acetoacetate enter the picture.

The reason a starving person can live for 40-60 days is precisely because we can turn fat into ketones and convert ketones into substrate for the Krebs Cycle in the mitochondria of our neurons. In fact, the more fat you have on your body, the longer you can survive. As an example of this, you may want to read this remarkable case report of a 382 day medically supervised fast (with only water and electrolytes)! If we had to rely on glucose, we’d die in a few days. If we could only rely on protein, we’d live a few more days but become completely debilitated with muscle wasting.

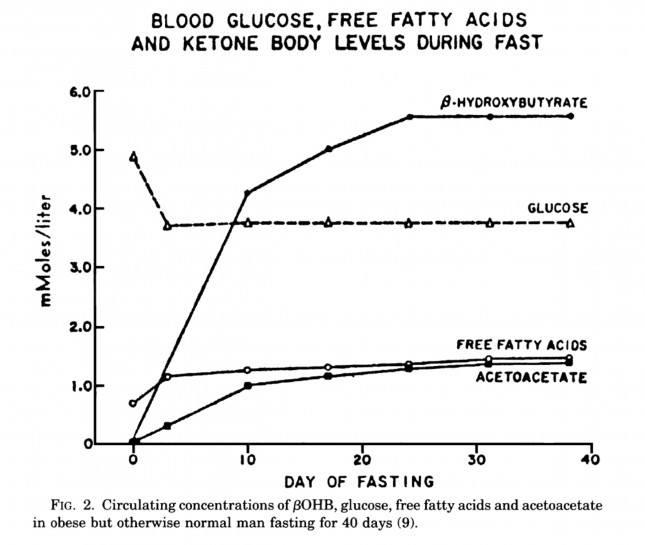

The graph below, also from the Cahill and Veech paper, shows the blood chemistry of a person starving for 40 days. Within about 3 days, a starving person’s level of glucose stops falling. Within about 10 days they reach a steady-state equilibrium with B-OHB levels exceeding glucose levels and offsetting most of the brain’s need for glucose. In fact, the late George Cahill did an experiment many years ago (probably would never get IRB approval to do such an experiment today) to demonstrate how ketones can offset glucose in the brain. Subjects with very high levels of B-OHB (about 5-7 mM) were injected with insulin until glucose levels reached 1 mM (about 19 mg/dL)! A normal person would fall into a coma at glucose levels below about 40 mg/dL and die by the time blood glucose reached 1 mM. These subjects were completely asymptomatic and 100% neurologically functional.

The last point I’ll make on the starving patient is that, as you can see in the figure below, the glucose level normalizes at about 65-70 mg/dL (about 3.7 mM) within days of fasting, despite no sources of exogenous glucose. Why? Because with so much fat being converted into B-OHB and acetoacetic acid by the liver, a significant amount of glycerol (the 3-carbon backbone of triglycerides) is liberated and converted by the liver into glycogen. As an aside, this is why someone in nutritional ketosis – even if eating zero carbohydrates – still has about 50-70% of a normal glycogen level, as demonstrated by muscle biopsies in such subjects.

Take home message #3: We evolved to produce ketone bodies so we could not only tolerate but also thrive in the absence of glucose for prolonged periods of time. No ability to produce ketone bodies = no human species.

Last point of background: Everything I’ve just presented is based on data from starving subjects. If one restricts carbohydrate intake, typically to less than about 20-50 gm/day (dependent on timing and carbohydrate composition), and maintains modest but not high protein intake (because protein is gluconeogenic – i.e., protein in excess will be converted to glycogen by the liver), one can induce a state referred to as “nutritional ketosis” with similar physiology to what I’ve just presented without resorting to starvation. Why you’d do this is something I will discuss later.

One other housekeeping issue: Ketosis versus DKA?

In a separate post, I explained the difference between nutritional ketosis (NK) and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). If this distinction is not clear, I’d suggest giving this separate post a quick skim for a refresher. DKA is a pathologic (i.e., harmful) state that results from the complete or near absence of insulin. This occurs in the setting of type 1 diabetes or very end-stage type 2 diabetes, and often as the result of a physiologic insult (e.g., an infection) where the patient is not receiving sufficient insulin to bring glucose into his cells. A person with a normal pancreas, regardless of how long he fasts (including the fellow I reference above who fasted for 382 days!) or how much he restricts carbohydrates, can not enter DKA because even a trace amount of insulin will keep B-OHB levels below about 7 or 8 mM, well below the threshold to develop the pathologic acid-base abnormalities associated with DKA. Let me reiterate, it is physiologically impossible to induce DKA in anyone that does not have T1D or very, very, very late-stage T2D with pancreatic “burnout.”

Embarrassing admission: I remember exactly where I was sitting in a clinic at Johns Hopkins in 2002 explaining to (admonishing, really) a patient who was on the Atkins diet how harmful it was because of DKA. I am so embarrassed by my complete stupidity and utter failure to pick up a single scientific article to fact check this dogma I was spewing to this poor patient. If you’re reading this, sir, please forgive me. You deserved a smarter doctor.

In Part II of this post I’ll tackle the questions I know folks still have on their mind (below). Until then, re-read this post to make sure you really understand this physiology. You’re already 10 steps ahead of the next person.

- Is there a “metabolic advantage” to being in ketosis?

- Are there dangers of being in ketosis?

- What are the most important things you need to know about getting into (or staying in) ketosis?