Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is currently the leading cause of death in the United States and globally. ASCVD is a chronic condition that is inevitable with aging, and, as we discussed in a recent AMA, the onset of ASCVD is more a matter of “when” rather than “if,” assuming one lives long enough. Research has shown that one of the strongest factors for reducing risk of ASCVD mortality is reduction of apoB particle number, which is typically estimated – albeit imperfectly – by measuring low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentrations. Not only is there a direct relationship between the relative risk of major cardiovascular events and apoB, but there is also a suspected relationship between reduction in ASCVD events and the duration of time over which lower apoB levels are maintained.

How much does lowering LDL-C affect mortality?

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) for LDL-C lowering drugs such as statins, ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors, and bile acid sequestrants have shown up to a 24% lower risk of major ASCVD events for every 1 mmol/L (38.7 mg/dL) reduction of LDL-C at one year of follow-up. Clinical studies have shown that statins and other LDL-lowering medications have their largest effect (on average, about a 39 mg/dL LDL-C reduction) in the first year of treatment, and the difference between LDL-C in the intervention and control groups decreases with each subsequent year. If the absolute value of circulating LDL-C was the only indicator of risk, the shrinking difference of LDL-C (down to about 19.4 mg/dL by year seven), should indicate that risk of ASCVD events is lowest in the first year on medication and steadily creeps up with every subsequent year of treatment. In other words, if the absolute LDL-C concentration at any snapshot in time were all that mattered, we’d expect that the risk reduction achieved with LDL-lowering treatments would slowly degrade with increasing time spent on these medications.

So what are the long-term benefits of LDL-C lowering medications?

As revealed by a recent meta-analysis by Wang et al., this gradual degradation is not the case. The investigators pooled 21 RCTs with the aim of evaluating the relationship between lipid-lowering drug exposure duration and risk of major cardiovascular events. This meta-analysis was limited to large, long-term RCTs of at least three years and the equivalent of 1000 patient-years of follow-up time. Importantly, the authors only included studies that reported results at each year of follow-up, providing multiple time points of data from each study. For each year of study, average LDL-C concentration of the control and treatment groups were pooled to show the absolute differences in LDL-C levels over time. Additionally, hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for each year of follow-up were extracted from published survival curves to assess the effect of duration on ASCVD risk reduction.

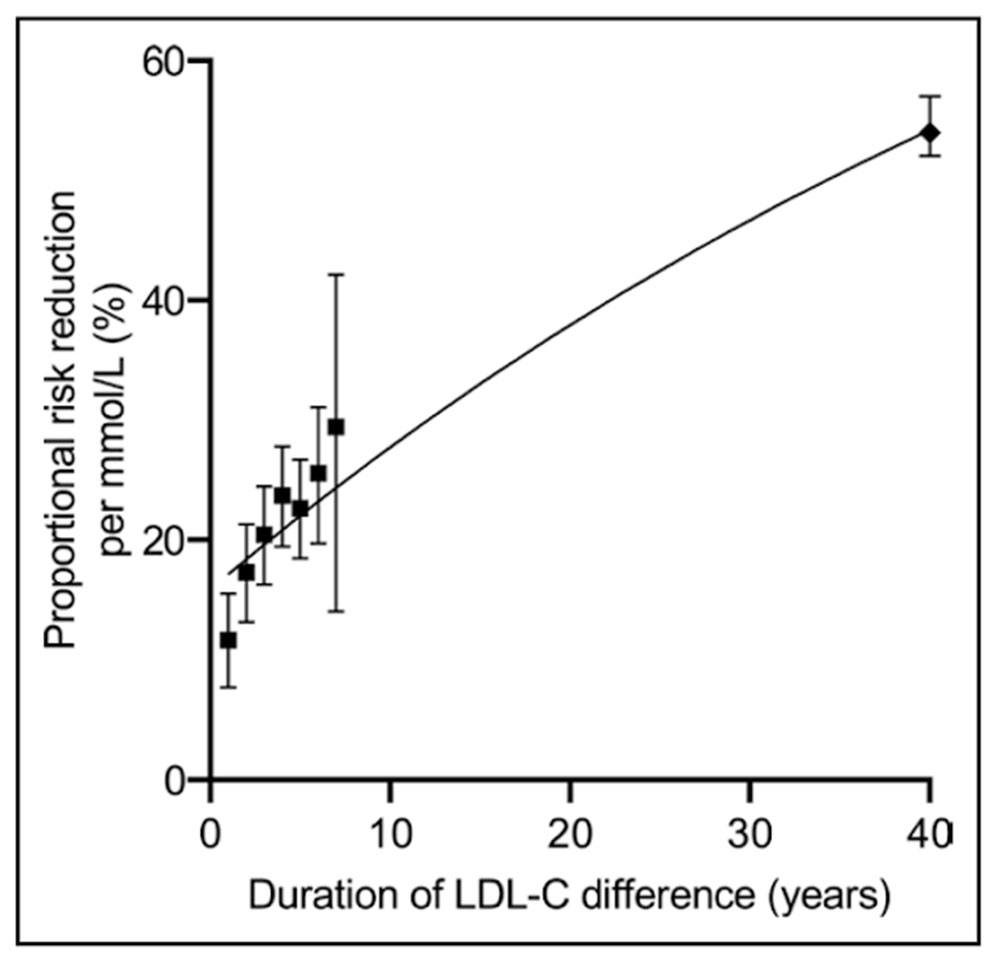

The pooled study analysis confirmed that lipid-lowering medications cause the greatest drop in LDL-C levels in the first year, and the difference between treatment and control groups diminishes with every year of follow-up thereafter. If the risk of cardiovascular events was solely dependent on the level of circulating LDL-C, then as the difference in LDL-C between treatment and control groups decreased with time, ASCVD risk should increase, relative to the controls. However, with each subsequent year of treatment with lipid-lowering drugs, the pooled analysis found a decrease in hazard ratio over time. One year of treatment was associated with a proportional risk reduction of 12% across analyzed studies, compared to a risk reduction of 23% after 5 years and 29% after 7 years. In other words, the relative protection afforded by LDL-lowering medications compounded with longer durations of use, such that the difference in CVD risk between treatment and control arms widened with each successive year – at least up to year seven, the longest study duration in the analysis.

How long do the cumulative effects continue?

Though RCTs on LDL-C lowering drugs have followed patients for no more than seven years, data from Mendelian randomization (MR) studies suggest that the cumulative effect of low LDL-C on ASCVD risk reduction may continue indefinitely throughout life. MR studies are based on the assumption that genetic variants influence the exposure variable of interest (in this case, LDL-C) and do not exert other effects that would contribute to the outcome of interest (in this case, major cardiovascular events). This means that any association observed between genetic variants and major cardiovascular events could only occur as a result of variation in LDL-C. Since genetic variants are randomly allocated at birth, they – unlike LDL-C itself – are largely unaffected by behavioral, socioeconomic, physiological, or other confounding variables, which would otherwise prohibit causal inference in observational studies. (For a more detailed understanding of MR, refer to this article in MIT Technology Review.)

MR studies examining genetic variants associated with LDL-C have revealed that, among subjects ages 40-80 years (mean 65.2 years), every 1 mmol/L (38.7 mg/dL) reduction in LDL-C was associated with a 54% reduction in risk of major coronary events. This risk reduction is nearly double that observed at 7 years of follow-up in the recent meta-analysis, suggesting that the beneficial effects of low exposure to LDL-C may continue to compound over decades of one’s life. (If you’re interested in reading more on this particular study, we did a deep dive newsletter when the study was first published.) Combining data from RCTs and MR studies, Wang et al. calculated the apparent trajectory of risk reduction as a function of duration of LDL-C reduction (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Plot of proportional risk reductions per mmol/L LDL-C difference versus duration, in RCTs and Mendelian randomization. From Wang et al., Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes, 2022

Figure 1: Plot of proportional risk reductions per mmol/L LDL-C difference versus duration, in RCTs and Mendelian randomization. From Wang et al., Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes, 2022

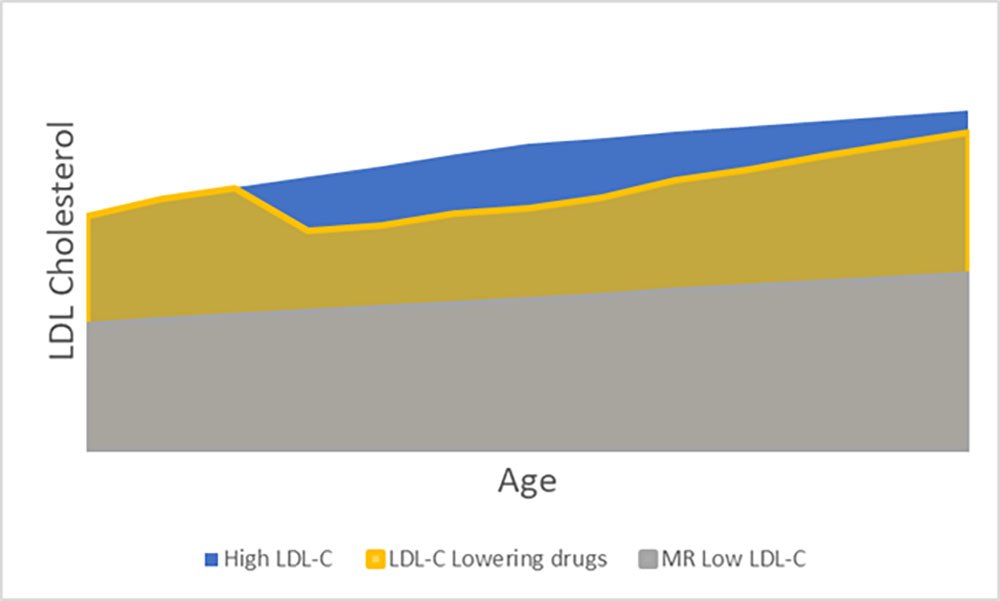

Now this doesn’t mean that once you start taking a lipid-lowering drug, your absolute risk of ASCVD events automatically keeps decreasing every year. Rather, the reduction in risk is relative to what it would be if left unmanaged. Recall the absolute difference in LDL-C between treatment and control groups decreased in subsequent follow up years. What this meta-analysis shows is that there is an integrated effect of the cumulative exposure to LDL-C – meaning we need to think about the area under the curve (AUC), which increases as a function of time in all individuals, though the total AUC value varies depending on LDL-C.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of hypothetical values for LDL-C vs. Age, illustrating how area under the curve changes with time.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of hypothetical values for LDL-C vs. Age, illustrating how area under the curve changes with time.

Consider the subjects in the MR study who have a genetic predisposition towards low LDL-C (Figure 2, shown in gray); with each year, these subjects accumulate a greater AUC (or overall more exposure to LDL-C) than they had the previous year. However, because LDL-C is low, this exposure accumulates much more slowly than in someone with a family history of high LDL-C (shown in blue), who reaches a larger “area” much more quickly. Now consider those with high LDL-C who start LDL management with medications relatively early (gold). In terms of LDL-C, these individuals will have their greatest deviation from their unmanaged peers within their first year of treatment, but even though that gap in absolute LDL-C narrows with each successive year, the gap in AUC between treated and untreated individuals continues to grow, resulting in an increase in risk reduction relative to untreated individuals, despite a simultaneous increase in absolute risk, which all individuals experience.

So what does this mean?

Not only do these study results impact how we think about LDL-C and risk of ASCVD today, but this also provides some insight into future treatments for lowering LDL-C. Advances in new LDL-C lowering pharmaceuticals will be able to exploit the compounding benefits of ASCVD risk reduction when lower LDL-C levels can be maintained for longer durations. For now, the value in using lipid-lowering drugs over a long duration is not simply a reduction in absolute LDL-C, but the reduction in accumulated exposure to LDL-C, which has prolonged benefits even as absolute levels of LDL-C increase over time. If the goal in preventing ASCVD is reducing the area under the curve of the LDL-C versus time function, time matters just as much as LDL-C reduction.